Ofgem Consultancy Services, Liquidity Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Document

esb inside 28/05/02 2:04 PM Page 1 esb inside 28/05/02 2:04 PM Page 2 CERTAINTY TRANSPARENCY LIQUIDITY REWARD NCB Corporate Finance 3 George’s Dock, IFSC, Dublin 1 Tel: +353-1-6115611 Contact: Andrew Ennis Commission for Energy Regulation Plaza House. Belgard Road, Tallaght, Dublin 24 Tel: +353-1-4000800 Contact: Eugene Coughlan NCB Corporate Finance, Authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland under the Investment Intermediaries Act, 1995. A member of the Royal Bank of Scotland Group esb inside 28/05/02 2:04 PM Page 3 esb inside 28/05/02 2:04 PM Page 4 Executive Summary esb inside 28/05/02 2:04 PM Page 5 Investing in the Irish Electricity Market NCB Corporate Finance was engaged by the Commission for Energy Regulation to carry out a review of the issues facing those considering investing in the Irish electricity market. Key Findings The relatively small size of Investing in the Irish Electricity Market, ESB dominance and uncertainty over future trading arrangements serve to reduce the attractiveness of the Irish market from both an investor’s and fi n a n c i e r ’ s point of view. Despite these issues, a number of parties remain interested in developing electricity generation and supply businesses in Ireland. The key difficulty facing those considering investing is the absence of a party to offer long-term offtake contracts to generators, which would enable the generators to obtain non recourse financing. It is likely that, in order to facilitate investment by a new generator, the current bilateral contracts based trading arrangements will have to be modified, in conjunction with the opportunity for IPPs to sell to ESB PES post 20 0 5 . -

ESB International's Smart Grid Solutions Team Conducts Factory Testing Circuits

THE NEWSPAPER FOR ESB Oct/Nov 2017 esb.ie/em RAHEENLEAGH FAMILY DAY PAGE 5 NEWS INNOVATION GENERATION & BSC & ELECTRIC ESB NETWORKS WHOLESALE MARKETS IRELAND PAGE 2 PAGE 10 PAGE 14 PAGE 19 PAGE 23 TOP STORIES IN BRIEF Raheenleagh Wind Farm POWER CHALLENGE 2017 holds family day Located on the Wicklow/Wexford border, Raheenleagh Wind Farm welcomed staff and their families CONTINUES TO BE A HIT! and friends on Saturday 12 August for the second family day to celebrate ESB's 90th anniversary. ESB International's head office wins major CSR award ESB International Head Office at One Dublin Airport Central has won a major Corporate Social Responsibility award at the fourteenth annual Chambers Ireland Corporate Social Responsibility awards ceremony. The award was won in the ‘Sustainable Buildings in Excellence in the Environment’ category for the recently redeveloped building. A lot of teamwork for this one… Two new Scottish wind farms Sarah Claxton and Marguerite in the works Sayers then tallied the scores and G&WM has announced that it has signed a development announced the winners at the even- services agreement with REG ing reception. Power Management, spanning two concept-stage wind farms Giving back in Scotland (Knockodhar and Some 35 teams took part in the Power Challenge Rebooted in Aghadoe, Co Kerry. As well as the teamwork and innova- Greenburn). tion, the weekend was about raising funds for three charities: the RNLI, Introducing ESB Energy ON FRIDAY 22 SEPTEMBER, with charity. Our performers came from in the dark wasn’t enough of a chal- St Vincent De Paul and Kerry Moun- ESB Energy, ESB's brand in a less-than-clement weather forecast a shortlist of those brave souls who lenge, the teams were mixed up, so tain Rescue. -

Industry Background

Appendix 2.2: Industry background Contents Page Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Evolution of major market participants ....................................................................... 1 The Six Large Energy Firms ....................................................................................... 3 Gas producers other than Centrica .......................................................................... 35 Mid-tier independent generator company profiles .................................................... 35 The mid-tier energy suppliers ................................................................................... 40 Introduction 1. This appendix contains information about the following participants in the energy market in Great Britain (GB): (a) The Six Large Energy Firms – Centrica, EDF Energy, E.ON, RWE, Scottish Power (Iberdrola), and SSE. (b) The mid-tier electricity generators – Drax, ENGIE (formerly GDF Suez), Intergen and ESB International. (c) The mid-tier energy suppliers – Co-operative (Co-op) Energy, First Utility, Ovo Energy and Utility Warehouse. Evolution of major market participants 2. Below is a chart showing the development of retail supply businesses of the Six Large Energy Firms: A2.2-1 Figure 1: Development of the UK retail supply businesses of the Six Large Energy Firms Pre-liberalisation Liberalisation 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 -

Da´Il E´Ireann

Vol. 585 Wednesday, No. 3 12 May 2004 DI´OSPO´ IREACHTAI´ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DA´ IL E´ IREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIU´ IL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Wednesday, 12 May 2004. Leaders’ Questions ……………………………… 533 Ceisteanna—Questions Taoiseach ………………………………… 542 Requests to move Adjournment of Da´il under Standing Order 31 ……………… 557 Order of Business ……………………………… 558 Health (Amendment) Bill 2004: Second Stage (resumed) …………………………… 566 Referral to Select Committee ………………………… 586 Ceisteanna—Questions (resumed) Minister for Communications, Marine and Natural Resources Priority Questions …………………………… 586 Other Questions …………………………… 598 Adjournment Debate Matters …………………………… 610 Estimates for Public Services: Message from Select Committee ……………… 610 Education for Persons with Disabilities Bill 2003: Order for Report Stage …………………………… 611 Report and Final Stages …………………………… 611 Private Members’ Business Management of Public Funds: Motion (resumed) ………………… 662 Message from Seanad ……………………………… 697 Adjournment Debate Schools Building Projects …………………………… 700 Child Care Services …………………………… 704 Questions: Written Answers …………………………… 709 533 534 DA´ IL E´ IREANN the past two years or so. At the time of the Good Friday Agreement the cases were still pending ———— and people had not been charged. However, we said that the McCabe killers would not be De´ Ce´adaoin, 12 Bealtaine 2004. included under the Good Friday Agreement, Wednesday, 12 May 2004. neither are they. That was over six years ago and we did not release the prisoners under that ———— scheme. Had that been the case, they would have been set free in 1998 or 1999, as all the prisoners Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar in Northern Ireland were. That question answers 10.30 a.m. itself, they were not released. What was being considered was the context in Paidir. -

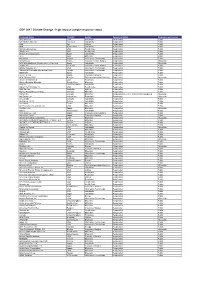

High Impact Sector Companies Analysed in the CDP Europe Report – 2019 Disclosure Year

High impact sector companies analysed in the CDP Europe Report – 2019 disclosure year The materials, energy and transport sectors, along with agriculture, comprise CDP’s high impact sectors. However due to lack of reporting data, the Agriculture sector was not included in the high- impact company analysis. Organization name Country Sector EVN AG Austria Electric utilities Mayr-Melnhof Karton Aktiengesellschaft Austria Paper & forestry OMV AG Austria Oil & gas Österreichische Post AG Austria Transport services VERBUND AG Austria Electric utilities Voestalpine AG Austria Steel Food, beverage & Anheuser Busch InBev Belgium tobacco Bekaert NV Belgium Metals & mining bpost Belgium Transport services Elia System Operator Belgium Electric utilities Fluxys Belgium Belgium Oil & gas Nyrstar NV Belgium Metals & mining Ontex Group NV Belgium Paper & forestry Solvay S.A. Belgium Chemicals CEZ Czechia Electric utilities A.P. Moller - Maersk Denmark Transport services Food, beverage & Carlsberg Breweries A/S Denmark tobacco Food, beverage & Chr. Hansen Holding A/S Denmark tobacco Dampskibsselskabet NORDEN A/S Denmark Transport services DFDS A/S Denmark Transport Services DSV A/S Denmark Transport services Novozymes A/S Denmark Chemicals Ørsted Denmark Electric utilities Finnair Finland Transport services Fortum Oyj Finland Electric utilities Huhtamäki Oyj Finland Paper & forestry Kemira Corporation Finland Chemicals Metsä Board Finland Paper & forestry Neste Oyj Finland Oil & gas Outokumpu Oyj Finland Steel Stora Enso Oyj Finland Paper & forestry UPM-Kymmene -

Connecting Jobs and Prosperity Eirgrid Plc Annual Report 2015 EIRGRID PLC ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2015

Connecting Jobs and Prosperity EirGrid plc Annual Report 2015 EIRGRID PLC ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2015 Contents 1 Who We Are 4 Chairperson’s Report 6 Chief Executive’s Review 8 The Transmission System 10 Financial Review 14 Focus On: Business Connections 16 Operations, Planning and Innovation 20 Consultation, Outreach and Engagement 22 Focus On: 12 Commitments 24 Developing the Grid 26 Focus On: Innovation 28 Market Operations 30 Focus On: Our Energy Performance 32 Our People 36 Focus On: Corporate Social Responsibility 38 The Board 46 Our Executive Team 51 Financial Statements EIRGRID PLC ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2015 Who We Are EirGrid Group is responsible for a safe, secure and reliable supply of electricity now; and in the future. We develop, manage and operate the electricity transmission grid. EirGrid Group is the independent Transmission System Operator (TSO) in Ireland and Northern Ireland, through EirGrid and SONI, respectively. We use the grid to connect industry and businesses that use large amounts of electricity. The grid also powers the distribution network - this supplies the electricity you use every day in your homes, businesses, schools, hospitals and farms. We support competition in energy, promote economic growth, facilitate more renewable energy and provide essential services. We develop new electricity infrastructure only when required. The Single Electricity Market Operator (SEMO) is part of the EirGrid Group, and operates the Single Electricity Market (SEM) across the two jurisdictions. EirGrid Group also owns and operates the East West Interconnector (EWIC), a high-voltage electricity link between Ireland and Great Britain. EirGrid plc is a commercial state-owned company. -

ICD Large Pp 1-64 RZ

Disseminating Best Practice Proceedings of the Information and Consultation Regional Seminar Series Disseminating Best Practice Proceedings of the Information and Consultation Regional Seminar Series Contents Foreword 4 Chapter 1 Overview of the ‘Disseminating Best Practice Project’ 6 Chapter 2 The European Employee Information and Consultation Directive, 2002 9 Chapter 3 Key Lessons from NCPP Case Study Report 13 Chapter 4 The Social Partner’s Perspective 22 Chapter 5 Disseminating Best Practice Seminar Series – Case Study Presentations 26 Chapter 6 Disseminating Best Practice Seminar Series – Dialogue and Debate 33 Appendix A Attendance List for Information and Consultation Conferences, 2004 40 4 Foreword The European Employee Information and Consultation Directive is due to be transposed into Irish law during the course of 2005. It is an important development in Irish employee relations, as it increases employee information and consultation rights. The National Centre for Partnership and Performance (NCPP) believes that it also represents an exciting opportunity to foster and deep- en partnership-style approaches to managing and anticipating change at the enterprise/organisational level. It was in this context that the National Centre for Partnership and Performance, funded by the EU Commission’s DG Employment and Social Affairs, undertook case study research into current information and consultation practices and procedures within fourteen public and private sector organisations in Ireland. The key findings and results of this project -

ESB Announces Annual Results for 2015

PRIZES AT THE RHA 186TH ANNUAL EXHIBITION THE NEWSPAPER FOR ESB PAGE 19 Apr/May 2016 esb.ie/em News Innovation Generation & BSC & Electric ESB Networks Ltd Wholesale Markets Ireland PAGE 02 PAGE 11 PAGE 14 PAGE 18 PAGE 23 tomers. Meanwhile the average Electric Ireland dual fuel cus Top stories in brief tomer (ie a customer with both Health Safety and Wellbeing electricity and gas) has seen sav Community gather ings of over €90 per annum since Friday 11th March was a November 2014. historical day for the Health Safety and Wellbeing community in ESB as it was the What does this mean for ESB? first time ever that staff working While 2015 has been challeng in these areas met from across ing in terms of intensifying com all of ESB group. Over 160 staff petition in the generation and from all business units as well as supply markets, it has been a staff from Corby, Coolkeeragh solid year in terms of our perfor and NIE were present. mance. Group Finance Director ESB’s connection to 1916 Donal Flynn explained profita The centenary of the 1916 Rising bility is important to pay the in has generated a lot of media terest on our borrowings (€215m coverage recently but did you in 2015), pay tax (€21m in 2015) know that a number of buildings and dividends (€273m in 2015), which ESB acquired or have leased repay our borrowings as they fall on a temporary basis following its due and reinvest very significant establishment in 1927 have a link Families and children all across Ireland actively participated in the launch of ESB Tree Week recently. -

ESB Investor Update

ESB Investor Update January 2020 www.esb.ie/ir 1 esb.ie/ir Disclaimer Forward looking statements: This presentation contains certain "forward-looking statements" with respect to ESB’s financial condition, results of operations and business and certain of ESB’s plans and objectives with respect to these items. By their very nature forward-looking statements are inherently unpredictable, speculative and involve risk and uncertainty because they relate to and depend upon future events and circumstances. There are a number of factors that could cause actual results and developments to differ materially from those expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. All forward-looking statements in the presentation are expressly qualified in their entirety by such factors. ESB does not intend to update any forward-looking statements. No warranty as to accuracy: Neither ESB nor any person acting on its behalf (i) makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained within this presentation or (ii) shall have any liability whatsoever for loss, howsoever arising, directly or indirectly, from use of the information contained within this presentation. No invitation to engage in investment activity: This presentation is not an offer to sell, exchange or transfer any securities of ESB and is not soliciting an offer to purchase, exchange or transfer such securities in any jurisdiction. Presentation not a prospectus: This presentation is not a prospectus for the purposes of -

Grid Export Data

CDP 2017 Climate Change - high-impact sample response status Company Name Country Sector Response Status Response permission 3M Company USA Industrials Responded Public A.P. Moller - Maersk Denmark Industrials Responded Public A2A Italy Utilities Responded Public ABB Switzerland Industrials Responded Public Abbott Laboratories USA Health Care Responded Public AbbVie Inc USA Health Care Responded Public Abertis Infraestructuras Spain Industrials Responded Public ACC India Materials Responded Public Accenture Ireland Information Technology Responded Public AccorHotels France Consumer Discretionary Responded Not public ACS Actividades de Construccion y Servicios Spain Industrials Responded Not public adidas AG Germany Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Adobe Systems, Inc. USA Information Technology Responded Public Advanced Semiconductor Engineering Taiwan Information Technology Responded Public AENA SA Spain Industrials Responded Public Aeon Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AFK Sistema JFSC Russia Telecommunication Services Responded Not public AFLAC Incorporated USA Financials Responded Public African Rainbow Minerals South Africa Materials Responded Public Aggreko United Kingdom Industrials Responded Public Agilent Technologies Inc. USA Health Care Responded Public AGL Energy Australia Utilities Responded Public Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited Canada Materials Responded Public Agrium Inc. Canada Materials Responded late, after analysis was completed Not public AIA Group Ltd. Hong Kong Financials Responded Not public Air Canada Canada Industrials Responded Public Air France - KLM France Industrials Responded Public Air Liquide France Materials Responded Public Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. USA Materials Responded Public Air Water Inc. Japan Materials Responded Not public Airbus Netherlands Industrials Responded Public Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Ajinomoto Co.Inc. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AK Steel Holding Corporation USA Materials Responded Not public AKÇANSA ÇİMENTO SANAYİ VE TİCARET A.Ş. -

INNOVATION for GENERATIONS Annual Report and Accounts 2013 Esb.Ie

INNOVATION FOR GENERATIONS Annual Report and Accounts 2013 esb.ie COVER_AR13_207X297.indd 1 13/03/2014 12:56 2 ESB Annual Report 2013 - Innovation for Generations ABOUT ESB ESB was established in 1927 as a corporate body in the Republic of Ireland under the Electricity (Supply) Act 1927. With a holding of 95%, ESB is majority owned by the Irish Government. The remaining 5% is held by an Employee Share Ownership Trust. As a strong, diversified, vertically integrated utility, ESB operates right across the electricity market: from generation, through transmission and distribution to supply. In addition, we extract further value at certain points along this chain: supplying gas, using our networks to carry fibre for telecommunications and more. With a regulated asset base (RAB) of approximately €8.5 billion, 42% of total electricity generation capacity in the all-island market and supplier of electricity to approximately 1.5 million customers throughout the island of Ireland, we are a leading Irish utility focussed on maintaining our financial strength and customer service. As at 31 December 2013, ESB Group employed approximately 7,490 people. ESB AR 2013 Ch0_NIC_V9.indd 2 13/03/2014 13:05 3 ESB Annual Report 2013 - Innovation for Generations CONTENTS 01 BUSINESS OVERVIEW 10 Chairman’s Statement 12 Chief Executive Review 13 Our Strategy 15 Business Environment Context For ESB 16 Strategy Our Strategy to 2025 18 Aims For 2025 19 02 OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW 20 Operating Environment 22 Finance Review 24 Business Unit Sections: ESB Generation -

Eirgrid Plc Annual Report 2010 Securing Ireland’S Electricity Supply Eirgrid Plc Plc Eirgrid Annual Report 2010 Report Annual

EirGrid plc Annual Report 2010 Securing Ireland’s Electricity Supply EirGrid plc Annual Report 2010 The Oval, The Oval, 160 Shelbourne Road, 160 Bóthar Shíol Bhroin, Ballsbridge, Droichead na Dothra, Dublin 4. Baile Átha Cliath 4. Tel +353 (0)1 677 1700 Teil +353 (0)1 677 1700 Fax +353 (0)1 661 5375 Faics +353 (0)1 661 5375 [email protected] www.eirgrid.com PRN A11/0158 EirGrid plc Annual Report & Accounts 2010 97 Glossary GROUP STRUCTURE APEx – Association of Power Exchanges CCGT – Combined Cycle Gas Turbine CER – Commission for Energy Regulation plc CGU – Cash Generating Unit CIGRE – International Council on Large Electric Systems CRM – Credit Risk Management CSR – Corporate and Social Responsibility DETI – Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment DSO – Distribution System Operator 75% EEPR – European Energy Programme for Recovery UK Holdings Limited EMS – Energy Management System ENTSO-E – European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity EWIC – East West Interconnector HAS – Harmonised Ancillary Services 25% HTLS – High-Temperature Low-Sag HVDC – High Voltage Direct Current Interconnector Limited Limited IBEC – Irish Business and Employers Confederation IFRS – International Financial Reporting Standards IWEA – Irish Wind Energy Association kV – Kilovolts MEC – Maximum Export Capacity MO – Market Operator TSO TSO MOUG – Market Operator User Group MW – Megawatt MWh – Megawatt Hours NCC – National Control Centre NIAUR – Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation PAC – Planning Appeals Commission RIDP – Renewable