Chikchi Temple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 GOC Chart As of August 1St 2012.Xlsx

2013 Games Organizing Committee Chart (As of August 1st, 2012) Chairwoman of 2013 GOC Chief Secretary 5th Na, Kyung Won Choi, Su Young Cho, Sung Jin The National Assembly Contract Employee Contract Employee 4th Officer of Audit & Inspection Secretary Secretary General of 2013 GOC Officer of Games Security 4th 4th 4th Jeon, Choon Mi Kwon, Oh Yeong Park, Hyun Joo Lim, Byoung Soo Kim, Ki Yong Jang, Chun Sik Park, Yoon Soo Lee, Chan Sub Donghae city The Board of Audit & Inspection of Korea Gangwon Province ormer Assistant Deputy Minister of MCS Gangwon Province Gangwon Province GW Police Agency Director General of Planning Bureau Director General of Competition Management Bureau Director General of Games Support Bureau Yi, Ki Jeong Cho, Kyu Seok Ahn, Nae Hyong Ministry of Culture, S & T Gangwon Province Ministry of Strategy & Finance Director of Planning & GA Departmen Director of Int'l Affairs Department Director of Competition Department Director of Facilities Department Director of HR & Supplies Departmen rector of Games Support Departme Jeon, Jae Sup Kim, Gyu Young Lee, Kang Il Lim, Seung Kyu Lee, Gyeong Ho Hong, Jong Yeoul Gangwon Province MOFAT Ministry of PA & Security Gangwon Province Gangwon Province Gangwon Province Manager of Planning Team anager of General Affairs Te Manager of Finance Team Manager of Protocol Team anager of Int'l Relations TeaManager of Immigration Tea anager of Credentialing Tea Manager of General Competitions Team Manager of Competition Support Tea Manager Snow Sports Team Manager of Ice Sports Team Manager -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

New Challenges Facing Asian Agriculture Under Globalisation

New Challenges Facing --------1-------- Asian Agriculture under Globalisation Volume II Edited by Jamalludin Sulaiman Fatimah Mohamed Arshad Mad Nasir Shamsudin 34 Farm Household Debt Problems in Jeonnom Province, Korea: ACose Study J.K. Park, P.S. Park and K.H. Song Introduction Farm loans have increased quite rapidly in the recent decades and the farm household debt 1 matter has become a serious socio-economic issue in Korea. In an effort to get around this critical issue, the government would prepare and implement impromptu new debt measures. Yet, the farm-debt ratio over farm income has been increasing very rapidly since the beginning of the WTO in 1995 and the IMF financial crisis of 1997, leading to 88 per cent as that of 2000, mainly due to low agricultural income. During the period of 1994 (the year right before the beginning of the WTO)-2000, farm household income had increased by 13.6 per cent but debt had increased by as much as 156.3 per cent (MAF, 2001 ). That is, farm household debt has been increasing very rapidly since 1995. Yet, the ratio of non-farm income accounted for around 32 per cent of farm income in recent years, which made it more difficult for farmers to repay their loans. This problem is getting even more complicated because of joint surety among the farmers, which would lead to total bankruptcy of farms including financially sound farms. Recently, more than 7 5 per cent of farm loans were utilised for the purpose of agricultural production. In order to cope with labour shortage problems due to the rural-urban migration of labour force, farmers began to purchase more agricultural machinery, which eventually led to the galloping farm household debts. -

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Books Sejong The Great, Hunminjeongeum . Joseoneohakhoe, 1946. Although we were only able to access it as an online database, this is the original document of the hunminjeongeum, the first book containing Hangul, written directly by King Sejong The Great. Through this we were able to see the first version of Hangul and how it looked like in the beginning of its creation, in comparison to what we use in the modern day. Journal Joseon Dynasty, The Joseonwangjo Sillok (The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty), Sejong vol.113, Seoul, 1444. Containing the official record of the Joseon dynasty during the time period in which Hangul was being invented, this source helped us understand more about what was going on in the Joseon empire during those times. By being able to access the official records during the time in Joseon’s changing culture, it was a significant source of information, narrowing down our research to a particular era in history. Images ‘Eongan (A letter from Hyojong to Princess Sookmyung -02)', 1623~1659, Center for Korean Studies Documents. This image, exclusively provided to us by the Center for Korean Studies, contains drafts of King Hyojong writing to Princess Sookmyung, his niece. These letters were written in Hangul, and we were able to use this as an example of how Hangul spread to higher classes. Hong-do, Kim. Seodang, www.museum.go.kr/files/upload/board/78/20101130165104.jpg. This painting depicts young children learning to read and write in little schoolyards called ‘Seodangs’. By using this in our website, we were able to show what education was like in early Joseon. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: UNTOLD STORIES: THE

ABSTRACT Title of Document: UNTOLD STORIES: THE OTHER KOREA Grace Pak, Master of Architecture, Spring 2015 Directed By: Professor Garth Rockcastle, Department of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation This thesis explores the dialectical tensions, ironies, and myths of North Korea, with the hope of exposing fallacies and bringing awareness to the crisis of the oppressed citizens of this hermetic country. There are discrepancies between the North Korea that most people know, and one that is lesser known, which contains the everyday stories of real people. The goal is to design a cultural landscape containing the narratives of the persecuted in an effort to promote understanding about a country that is largely misinterpreted because of the images the Kim dictatorship and international media have planted in the minds of many people. The architecture provides a ground for commentary on the truth and what can be done to change the current state of apathy, ignorance, and helplessness. Acts of violation against humanity that continue in North Korea must be stopped. The fact that the North and South must reunite to save the citizens of North Korea is a pressing issue that the South Koreans must genuinely want in order to create change. Gathering information about Korea’s history and attributes of the proposed site will reveal how time changes space, the way our memories and ideas are both temporal and timeless as they are exchanged. When we become more aware of the issues at large, it will change our indifference and help us react to the stories that are told. UNTOLD STORIES: THE OTHER KOREA By Grace J. -

Anecdotes of Kim Jong Il's Life 2

ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA JUCHE 104 (2015) At the construction site of the Samsu Power Station (March 3, 2006) At the Migok Cooperative Farm in Sariwon (December 3, 2006) At the Ryongsong Machine Complex (November 12, 2006) In a fish farm at Lake Jangyon (February 6, 2007) At the Kosan Fruit Farm (May 4, 2008) At the goat farm on the Phyongphung Tableland in Hamju County (August 7, 2008) With a newly-wed couple of discharged soldiers at the Wonsan Youth Power Station (January 5, 2009) At the Pobun Hermitage in Mt. Ryongak (January 17, 2009) At the Kumjingang Kuchang Youth Power Station (November 6, 2009) CONTENTS 1. AFFECTION AND TRUST .......................................................1 “Crying Faces Are Not Photogenic”........................................1 Laughter in an Amusement Park..............................................2 Choe Hyon’s Pistol ..................................................................3 Before Working Out the Budget ..............................................5 Turning “100m Beauty” into “Real Beauty”............................6 The Root Never to Be Forgotten..............................................7 Price of Honey .........................................................................9 Concrete Stanchions Removed .............................................. 10 -

A Utumn 2012

Vol. 5 No. 3 5 No. Vol. Autum 2012 Autum Autumn 2012 Vol. 5 No. 3 1 | 1 Quarterly Magazine of the Cultural Heritage Administration Autumn 2012 Vol. 5 No. 3 Cover White Symbolizes autumn. The symbolism originates from the traditional "five direc- tional colors" based on the ancient Chinese thought of wuxing, or ohaeng in Korean. The five colors were associated with seasons and other phenomena in nature, including the fate of humans. The cover design features gat, the fine horsehair hat for Korean men. For more stories about this, see p. 44. KOREAN HERITAGE is also available on the website (http://English.cha.go.kr) and smart devices. 2 | 3 CHA News Vignettes Korean Folk Customs East Asia’s First Neolithic Farm Site Found Hand-turned Millstone The National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage held a briefing on June 26 at A traditional Korean-style hand mill, called an excavation site assumed to be the first Neolithic farm field ever found in East maetdol, typically consists of two flat, round Asia. Presumably dating to 3600-3000 B.C., the locale at Munam-ri, Goseong stones: a stationery bed stone and an upper County, Gangwon Province has yielded fragments of comb-patterned pottery, stone stone that has a vertical wooden handle arrowheads and a dwelling site. Further analysis of the findings is planned for more to spin it on a steel pivot, crushing grain. precise dating of the site, which shows more primitive traces than Bronze Age This ancient household item evolved from agricultural sites. grinding stones of earlier times. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

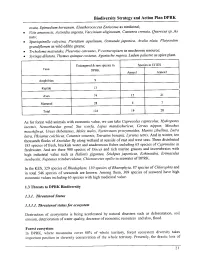

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Development of Streamflow Drought Severity–Duration–Frequency Curves

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 3341–3351, 2014 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/18/3341/2014/ doi:10.5194/hess-18-3341-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Development of streamflow drought severity–duration–frequency curves using the threshold level method J. H. Sung1 and E.-S. Chung2 1Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Yeongsan River Flood Control Office, Gwangju, Republic of Korea 2Department of Civil Engineering, Seoul National University of Science & Technology, Seoul, 139-743, Republic of Korea Correspondence to: E.-S. Chung ([email protected]) Received: 5 October 2013 – Published in Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 3 December 2013 Revised: 16 July 2014 – Accepted: 22 July 2014 – Published: 3 September 2014 Abstract. This study developed a streamflow drought also derived to quantify the extent of the drought duration. severity–duration–frequency (SDF) curve that is analogous These curves can be an effective tool to identify streamflow to the well-known depth–duration–frequency (DDF) curve droughts using severities, durations, and frequencies. used for rainfall. Severity was defined as the total water deficit volume to target threshold for a given drought dura- tion. Furthermore, this study compared the SDF curves of four threshold level methods: fixed, monthly, daily, and de- 1 Introduction sired yield for water use. The fixed threshold level in this study is the 70th percentile value (Q70) of the flow dura- The rainfall deficiencies of sufficient magnitude over pro- tion curve (FDC), which is compiled using all available daily longed durations and extended areas and the subsequent re- streamflows. The monthly threshold level is the monthly ductions in the streamflow interfere with the normal agricul- varying Q70 values of the monthly FDC. -

THE 16Th INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM on RIVER and LAKE ENVIRONMENTS “Climate Change and Wise Management of Freshwater Ecosystems”

THE 16th INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON RIVER AND LAKE ENVIRONMENTS “Climate Change and Wise Management of Freshwater Ecosystems” 24-27 August, 2014 Ladena Resort, Chuncheon, Korea Organized by Steering Committee of ISRLE, Korean Society of Limnology, Chuncheon Global Water Forum Sponsored by Japanese Society of Limnology Chinese Academy of Science International Association of Limnology (SIL) Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) Gangwondo Provincial Government 江原道 Korean Federation of Science and Technology Societies Korea Federation of Water Science and Engineering Societies Institute of Environmental Research at Kangwon National University K-water Halla Corporation Assum Ecological Systems INC. ISRLE-2014 Scientific Program Schedule Program 24th Aug. 2014 15:00 - Registration 15:00 - 17:00 Bicycle Tour 17:30 - 18:00 Guest Editorial Board Meeting for Special Issue(Coral) 18:00 - 18:30 Steering Committee Meeting(Coral) 19:00 - 21:00 Welcome reception 25th Aug. 2014 08:30 - 09:00 Registration 09:00 - 09:30 Opening Ceremony and Group Photo 09:30 - 10:50 Plenary Lecture-1(Diamond) 10:50 - 11:10 Coffee break 11:10 - 12:25 Oral Session-1(Diamond), Oral Session-2(Emerald) 12:25 - 13:30 Lunch 13:30 - 15:30 Oral Session-3(Diamond). Oral Session-4(Emerald) 15:30 - 15:50 Coffee break 15:50 - 18:00 Poster Session Committee Meeting of Korean Society of Limnology General 17:00 - 18:00 Assembly Meeting of Korean Society of Limnology(Diamond) 18:00 - 21:00 Dinner party 26th Aug. 2014 09:00 - 10:20 Plenary Lecture-2(Diamond) 10:20 - 10:40 Coffee break 10:40 - 12:40 Oral Session-5(Diamond), Oral Session-6(Emerald) 12:40 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 16:00 Young Scientist Forum(Diamond), Oral Session-7(Emerald) 16:00 - 16:20 Coffee break 16:20 - 18:05 Oral Session-8(Diamond), Oral Session-9(Emerald) 18:05 - 21:00 Banquet 27th Aug. -

The Samurai Invasion of Korea 1592–98

CAM198cover.qxd:Layout 1 25/3/08 13:41 Page 1 CAMPAIGN • 198 Accounts of history’s greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics and battle experiences of the opposing forces throughout the crucial stages of each campaign 198 • CAMPAIGN THE SAMURAI INVASION OF KOREA THE SAMURAI INVASION 1592–98 OF KOREA 1592–98 OF KOREA 1592–98 THE SAMURAI INVASION The invasions of Korea launched by the dictator Toyotomi Hideyoshi are unique in Japanese history for being the only time that the samurai assaulted a foreign country. Hideyoshi planned to invade and conquer China, ruled at the time by the Ming dynasty, and when the Korean court refused to allow his troops to cross their country, Korea became the first step in this ambitious plan of conquest. Though ultimately ending in failure and retreat, the Japanese armies initially drove the Koreans all the way to China before the decisive victories of Admiral Yi Sunsin and the Korean navy disrupted the Japanese supply routes whilst Chinese armies harried them by land. This book describes the region’s first ‘world war’ that caused a degree of devastation in Korea itself that was unmatched until the Korean War of the 1950s. Full colour battlescenes Illustrations 3-dimensional ‘bird’s-eye-views’ Maps STEPHEN TURNBULL US $19.95 / CAN $22.95 ISBN 978-1-84603-254-7 OSPREY 51995 PUBLISHING 9 781846 032547 O SPREY WWW.OSPREYPUBLISHING.COM STEPHEN TURNBULL ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAM198title.qxd:Layout 1 25/3/08 10:41 Page 1 CAMPAIGN • 198 THE SAMURAI INVASION OF KOREA 1592–98 STEPHEN TURNBULL ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAM198 Korea final.qxd:Layout 1 25/3/08 13:53 Page 2 First published in Great Britain in 2008 by Osprey Publishing, DEDICATION Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA To Richard and Helen on the occasion of their wedding, 23 August 2008. -

Truth and Reconciliation� � Activities of the Past Three Years�� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

Truth and Reconciliation Activities of the Past Three Years CONTENTS President's Greeting I. Historical Background of Korea's Past Settlement II. Introduction to the Commission 1. Outline: Objective of the Commission 2. Organization and Budget 3. Introduction to Commissioners and Staff 4. Composition and Operation III. Procedure for Investigation 1. Procedure of Petition and Method of Application 2. Investigation and Determination of Truth-Finding 3. Present Status of Investigation 4. Measures for Recommendation and Reconciliation IV. Extra-Investigation Activities 1. Exhumation Work 2. Complementary Activities of Investigation V. Analysis of Verified Cases 1. National Independence and the History of Overseas Koreans 2. Massacres by Groups which Opposed the Legitimacy of the Republic of Korea 3. Massacres 4. Human Rights Abuses VI. MaJor Achievements and Further Agendas 1. Major Achievements 2. Further Agendas Appendices 1. Outline and Full Text of the Framework Act Clearing up Past Incidents 2. Frequently Asked Questions about the Commission 3. Primary Media Coverage on the Commission's Activities 4. Web Sites of Other Truth Commissions: Home and Abroad President's Greeting In entering the third year of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea (the Commission) is proud to present the "Activities of the Past Three Years" and is thankful for all of the continued support. The Commission, launched in December 2005, has strived to reveal the truth behind massacres during the Korean War, human rights abuses during the authoritarian rule, the anti-Japanese independence movement, and the history of overseas Koreans. It is not an easy task to seek the truth in past cases where the facts have been hidden and distorted for decades.