Case Studies of Focal Prefrontal Lesions in Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lack of Motivation: Akinetic Mutism After Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Netherlands Journal of Critical Care Submitted October 2015; Accepted March 2016 CASE REPORT Lack of motivation: Akinetic mutism after subarachnoid haemorrhage M.W. Herklots1, A. Oldenbeuving2, G.N. Beute3, G. Roks1, G.G. Schoonman1 Departments of 1Neurology, 2Intensive Care Medicine and 3Neurosurgery, St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg, the Netherlands Correspondence M.W. Herklots - [email protected] Keywords - akinetic mutism, abulia, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cingulate cortex Abstract Akinetic mutism is a rare neurological condition characterised by One of the major threats after an aneurysmal SAH is delayed the lack of verbal and motor output in the presence of preserved cerebral ischaemia, caused by cerebral vasospasm. Cerebral alertness. It has been described in a number of neurological infarction on CT scans is seen in about 25 to 35% of patients conditions including trauma, malignancy and cerebral ischaemia. surviving the initial haemorrhage, mostly between days 4 and We present three patients with ruptured aneurysms of the 10 after the SAH. In 77% of the patients the area of cerebral anterior circulation and akinetic mutism. After treatment of the infarction corresponded with the aneurysm location. Delayed aneurysm, the patients lay immobile, mute and were unresponsive cerebral ischaemia is associated with worse functional outcome to commands or questions. However, these patients were awake and higher mortality rate.[6] and their eyes followed the movements of persons around their bed. MRI showed bilateral ischaemia of the medial frontal Cases lobes. Our case series highlights the risk of akinetic mutism in Case 1: Anterior communicating artery aneurysm patients with ruptured aneurysms of the anterior circulation. It A 28-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history is important to recognise akinetic mutism in a patient and not to presented with a Hunt and Hess grade 3 and Fisher grade mistake it for a minimal consciousness state. -

Bibliothèque De Flers Et À Divers

BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE Commissaires-Priseurs Bibliothèque de Flers et à divers Alain NICOLAS Expert PARIS – DROUOT – 13 JUIN 2014 Ci-dessus : Voltaire, n° 203 En couverture : Mucha - Flers, n° 168 BIBLIOTHÈQUE DE FLERS et à divers VENDREDI 13 JUIN 2014 à 14 h Par le ministère de Mes Eric BEAUSSANT et Pierre-Yves LEFÈVRE Commissaires-Priseurs associés Assistés de Michel IMBAULT BEAUSSANT LEFÈVRE Société de ventes volontaires Siren n° 443-080 338 - Agrément n° 2002-108 32, rue Drouot - 75009 PARIS Tél. : 01 47 70 40 00 - Télécopie : 01 47 70 62 40 www.beaussant-lefevre.com E-mail : [email protected] Assistés par Alain NICOLAS Expert près la Cour d’Appel de Paris Assisté de Pierre GHENO Archiviste paléographe Librairie « Les Neuf Muses » 41, Quai des Grands Augustins - 75006 Paris Tél. : 01.43.26.38.71 - Télécopie : 01.43.26.06.11 E-mail : [email protected] PARIS - DROUOT RICHELIEU - SALLE n° 7 9, rue Drouot - 75009 Paris - Tél. : 01.48.00.20.20 - Télécopie : 01.48.00.20.33 EXPOSITIONS – chez l’expert, pour les principales pièces, du 5 au 10 Juin 2014, uniquement sur rendez-vous – à l’Hôtel Drouot le Jeudi 12 Juin de 11 h à 18 h et le Vendredi 13 Juin de 11 h à 12 h Téléphone pendant l’exposition et la vente : 01 48 00 20 07 Ménestrier, n° 229 CONDITIONS DE LA VENTE Les acquéreurs paieront en sus des enchères, les frais et taxes suivants : pour les livres : 20,83 % + TVA (5,5 %) = 21,98 % TTC pour les autres lots : 20,83 % + TVA (20 %) = 25 % TTC La vente est faite expressément au comptant. -

Outcomes in Neuroscience Education: Modular Theory and Network Theory Thomas Romanchek

Outcomes in Neuroscience Education: Modular Theory and Network Theory Thomas Romanchek A Prelude to Modular Theory and lectures of Gall, his collaborators, and his students Few can contest the complicated and interdisci- spread throughout the English-speaking world during the plinary origins of neuroscientific study, as its precise date of 19th century and fomented a number of debates about the birth is obscure. However, it is important to place the first methods employed to justify the major principles of phre- true and deliberate neuroscience studies in proper histori- nology (Yildirim & Sarikcioglu, 2004). Physiologist Jean cal context so we can fully appreciate and understand why Pierre Flourens performed experimental brain excisions topics were studied through the lens of modular theory. on pigeons and Ancient Egyptians considered the brain and its organic observed their projections to be little more than waste, instead believing consequential that the true “seat of the soul” was the heart (Chudler, n.d.). behavior to This view was replicated in early Greek and biblical texts demonstrate but represented the consolidation of personality and human that the defined character into physiological terms. Later, Hippocrates brain regions and his followers rebuked this dogma in early physiology, in phrenology instead arguing that the brain was the major control center had little experi- for the body and possessed three ventricles, each of which mental backing. Figure 2: Blausen.com staff (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 [png]. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_brain#/media/File:Blausen_0102_ was responsible for a different mental faculty: imagination, These ablations, Brain_Motor&Sensory_(flipped).png reason, and memory (Chudler, n.d.). -

Steroid-Responsive Encephalitis Lethargica Syndrome with Malignant Catatonia

□ CASE REPORT □ Steroid-Responsive Encephalitis Lethargica Syndrome with Malignant Catatonia Yoichi Ono 1, Yasuhiro Manabe 1, Yoshiyuki Hamakawa 1, Nobuhiko Omori 1 and Koji Abe 2 Abstract We report a 47-year-old man who is considered to have sporadic encephalitis lethargica (EL). He presented with hyperpyrexia, lethargy, akinetic mutism, and posture of decorticate rigidity following coma and respira- tory failure. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy improved his condition rapidly and remarkably. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed severe diffuse slow waves of bilateral frontal dominancy, and paral- leled the clinical course. Our patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for malignant catatonia, so we diagnosed secondary malignant catatonia due to EL syndrome. The effect of corticosteroid treatment remains controver- sial in encephalitis; however, some EL syndrome patients exhibit an excellent response to corticosteroid treat- ment. Therefore, EL syndrome may be secondary to autoimmunity against deep grey matter. It is important to distinguish secondary catatonia due to general medical conditions from psychiatric catatonia and to choose a treatment suitable for the medical condition. Key words: encephalitis lethargica, catatonia, steroid therapy (DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6179) Introduction Case Report Encephalitis lethargica (EL), named by von Economo, is A 47-year-old man, who had a past history of delusional severe encephalitis which appeared in epidemic form in disorder for about 2 years, developed a pyrexia, vomiting Europe and elsewhere towards the end of World War I and and diarrhea. He was brought to our hospital because his lasted into the 1920’s (1, 2). Since then, occasional cases condition had deteriorated. On admission, his examination that resembled EL syndrome have been described in the showed a body temperature of 39℃ and systolic blood pres- medical literature. -

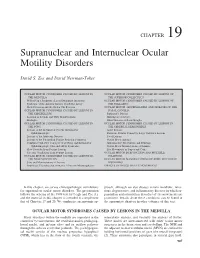

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

Peter Kropotkin and the Social Ecology of Science in Russia, Europe, and England, 1859-1922

THE STRUGGLE FOR COEXISTENCE: PETER KROPOTKIN AND THE SOCIAL ECOLOGY OF SCIENCE IN RUSSIA, EUROPE, AND ENGLAND, 1859-1922 by ERIC M. JOHNSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May 2019 © Eric M. Johnson, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: The Struggle for Coexistence: Peter Kropotkin and the Social Ecology of Science in Russia, Europe, and England, 1859-1922 Submitted by Eric M. Johnson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Examining Committee: Alexei Kojevnikov, History Research Supervisor John Beatty, Philosophy Supervisory Committee Member Mark Leier, History Supervisory Committee Member Piers Hale, History External Examiner Joy Dixon, History University Examiner Lisa Sundstrom, Political Science University Examiner Jaleh Mansoor, Art History Exam Chair ii Abstract This dissertation critically examines the transnational history of evolutionary sociology during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Tracing the efforts of natural philosophers and political theorists, this dissertation explores competing frameworks at the intersection between the natural and human sciences – Social Darwinism at one pole and Socialist Darwinism at the other, the latter best articulated by Peter Alexeyevich Kropotkin’s Darwinian theory of mutual aid. These frameworks were conceptualized within different scientific cultures during a contentious period both in the life sciences as well as the sociopolitical environments of Russia, Europe, and England. This cross- pollination of scientific and sociopolitical discourse contributed to competing frameworks of knowledge construction in both the natural and human sciences. -

The Locked-In Syndrome: a Review and Presentation of Two Chronic Cases

Paraplegia28 (1990) 5-16 0031-1758/90/0028-0005$10,00 © 1990 International Medical Society ofParapiegia Paraplegia The Locked-in Syndrome: A Review and Presentation of Two Chronic Cases P. Dollfus, MD,l P. L. Milos, MD,(th A. Chapuis, MD,l P. Real, MD,2 M. Orenstein, MD,2 J. W. Soutter, MD2 lCentre de Readaptation, 57 rue Albert Camus, 68093 Mulhouse Cedex, France, 2Centre Hospitalier de Mulhouse, B.P. 1070,68051 Mulhouse Cede x, France. Summary The locked-in syndrome (LIS) is a state of an upper motor neurone quadriplegia involving the cranial nerve pairs with usually a lateral gaze palsy, paralytic mutism, full consciousness and awareness by the patient of his environment. A his torical presentation of the LIS is given as well as a short description of the clinicoana tomic lesion causing LIS. The usual cause is vascular and corresponds to a pontine infarction due to an obstruction of the basilar artery but other lesions in the brain stem can also be the cause. Non-vascular aetiologies, especially traumatic, are reviewed. The use of electroencephalography (EEG), brain auditory evoked poten tials (BAEP) and somesthesic evoked potentials (SEP) are discussed as well as the use in the acute stage of computed tomography (CT), angiography, and magnetic resonance imagery (MR/). The last method may show well delineated ischaemic lesions some time after the event. The communication disability is probably the most difficult to overcome. Two cases of LIS are presented. Key words: Tetraplegia; Locked-in Syndrome; Pontine Infarction; Communica tion Disability. The locked-in syndrome (LIS), a term which has been finally adopted since the publication by Plum and Posner in 1966, was, in fact, described more than 100 years ago, by Alexandre Dumas (father) who depicted in 1846 quite accur ately in his novel'T he Count of Monte Cristo', Monsieur Noirtier as a'corpse with living eyes'. -

A Rare Case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in an 80-Year-Old Male

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.10038 A Rare Case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in an 80-Year-Old Male Mario Dervishi 1 , Travis Lambert 1 , Maria Markosyan Karapetyan 2 , Nader Warra 3 , Ziyad Iskenderian 2 1. Internal Medicine, American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine, Cupecoy, SXM 2. Internal Medicine, Ascension Providence Hospital, Southfield, USA 3. Neurology, Ascension Providence Hospital, Southfield, USA Corresponding author: Mario Dervishi, [email protected] Abstract Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare, rapid and fatal human prion disease that causes neurodegeneration. Rapidly progressive dementia, quick involuntary muscle jerking and specific radiographic and laboratory findings are characteristic of the disease. CJD should not be ruled even if the clinical presentation is outside the common age range. Herein we present a case of an 80-year-old man with probable diagnosis of CJD. The absolute diagnosis of CJD can only be confirmed post-mortem with a brain biopsy. Categories: Internal Medicine, Neurology Keywords: creutzfeldt-jakob disease, prion diseases, neurodegenerative disorders Introduction Prion diseases are a cluster of neurodegenerative pathologies caused by misfolding of proteins called prion [1]. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is the most common form and accounts for more than 90% of human prion diseases, although it is still rare with 350 cases per year reported in the United States [2]. This disease typically presents with rapid course of symptomatology and the unfortunate, inevitable fate is death. Amongst subtypes (sporadic, familial, iatrogenic and variant), sporadic CJD is the most common form seen in 85%-90% of cases. Disease most commonly affects people of ages 50-70 years, with both genders equally affected [3]. -

Luigi Luciani (1840-1919) - the Italian Claude Bernard with German Shaping, and His Studies on the Cerebellum with Projections to Nowadays

Rev Bras Neurol. 55(3):33-37, 2019 NOTA HISTÓRICA Luigi Luciani (1840-1919) - the Italian Claude Bernard with German shaping, and his studies on the cerebellum with projections to nowadays. Luigi Luciani (1840-1919) - o italiano Claude Bernard com formação alemã, e seus estudos sobre o cerebelo com projeções na atualidade. RESUMO ABSTRACT Luigi Luciani (1840-1919) was an illustrious Italian citizen and physio- Luigi Luciani (1840-1919) foi um ilustre cidadão e fisiologista italia- logist whose research scope covered mainly cardiovascular subjec- no, cujo escopo de pesquisa abrangia principalmente assuntos car- ts, the nervous system, and fasting. He published in 1891 a modern diovasculares, sistema nervoso e jejum. Ele publicou em 1891 um landmark of the study of cerebellar physiology - “Il cervelletto: nuo- marco moderno do estudo da fisiologia do cerebelo - “Il cervelletto: vistudi di normal and pathología physiology” / “The cerebellum: new nuovistudi di fisiologia normale and patologica” / ”O cerebelo: novos studies on normal and pathological physiology.” In his experiment, estudos sobre fisiologia normal e patológica”. Em seu experimento, a dog survived after cerebellectomy, reporting a triad of symptoms um cão sobreviveu após a cerebelectomia, com o relatório de uma (asthenia, atonia, and astasia). In this way, the eminent neurophy- tríade de sintomas (astenia, atonia e astasia). Dessa maneira, o emi- siologist improved the operative technique and sterile processes to nente neurofisiologista aprimorou a técnica operatória e os proces- -

Flourens, Pierre

Thomas, R. K. (2012). Flourens, Pierre. In Encyclopedia of the history of psychological theories (Vol. 1, pp. 442-443. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Manuscript Version. ©Springer-Verlag holds the Copyright If you wish to quote from this entry you must consult the Springer-Verlag published version for precise location of page and quotation Flourens, Pierre Roger K. Thomas1 ~ (1) Department of Psychology, University of Georgia, 30602-3013 Athens, GA, USA ~ Roger K. Thomas Email: [email protected] Without Abstract Basic Biographical Information Flourens (1794-1867) was born in Maureilhan, France. Somewhat of a prodigy, he earned a medical degree at the age of 19 from the Faculte de Medecine at Montpelier. Subsequently, Flourens became a protege of Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), the eminent scientific paleontologist and leader of the comparative method in organismal biology. Under Cuvier's guidance, Flourens began the work for which he is most recognized, comparative experimental brain research. Flourens articles on brain research in 1822 and 1823 were presented to the Academie des Sciences by Cuvier. These were then assembled together with a newly written preface to become Flourens' first important book, Recherches experimentales sur les proprietes et les fonctions du systeme nerveux dans les animaux vertebres (1824). By 1828, with Cuvier's sponsorship, Flourens was admitted to the Academie des Sciences, and upon Cuvier's death in 1833 and by his recommendation, Flourens was appointed secretaire perpetual of the Academie. In 1840, he was elected over Victor Hugo to the Academie de France. Flourens soon had a professorship in comparative anatomy at the museum of the Jardin de Roi, and in 1855, he was appointed professor of natural history in the College de France where he remained until his death (Pearce 2008). -

Recherches Sur Diderot Et Sur L'encyclopédie

Recherches sur DIDEROT et sur l’ENCYCLOPÉDIE Revue annuelle ¢ no 49 ¢ 2014 publiée avec le concours du Centre national du Livre, du conseil général de la Haute-Marne ISSN : 0769-0886 ISBN : 978-2-9520898-7-6 © Société Diderot, 2014 Toute reproduction même partielle est formellement interdite Diffusion : Amalivre 62, avenue Suffren 75015 Paris Présentation Diderot penseur politique et critique d’art sont les thèmes sur lesquels s’ouvre cette livraison des RDE. Sur ce qu’il nomme « les limites du politique », on lira la réflexion majeure de Georges Benre- kassa, retraçant les voies qui, de la question frumentaire à l’expérience russe et aux derniers écrits, l’Histoire des deux Indes et l’Essai sur Sénèque, menèrent Diderot vers une conception critique complexe de l’espace et de l’action politiques. La critique d’art ensuite ¢ et nous sommes heureux, à cette occasion, d’offrir des planches en couleurs à nos lecteurs. L’Accordée de village... On croyait que tout avait été dit sur le célèbre tableau de Greuze et sur son commentaire dans le Salon de 1761 ; à tort, car Jean et à Antoinette Ehrard, questionnant de façon neuve le propos de Diderot, font surgir de l’étude rigoureuse des mots employés et de leur sens à l’époque, une réflexion sur la paternité qui engage profondément la sensibilité diderotienne. Quelles œuvres Diderot a-t-il réellement vues lors de ses visites aux galeries de Dusseldorf et de Dresde ? Daniel Droixhe, tout en soulignant la singulière sensibilité de Diderot à la construction pictu- rale, corrige certaines des erreurs d’identification commises par le voyageur lui-même ou par ses commentateurs; l’identité des visiteurs de ces galeries signale, en outre, l’existence d’un véritable réseau de sociabilité franco-hollando-germanique. -

Akinetic Mutism As a Classification Criterion for the Diagnosis Of

524 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:524–528 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.64.4.524 on 1 April 1998. Downloaded from Akinetic mutism as a classification criterion for the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Anke Otto, Inga Zerr, Maria Lantsch, Kati Weidehaas, Christian Riedemann, Sigrid Poser Abstract damage among which are processes of brain Objectives—Among the classification cri- degeneration and circumscribed cerebral le- teria for the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt- sions, above all bilateral frontal and mesodien- Jakob disease, akinetic mutism is cephalic lesions. Several authors suggested described as a symptom which helps to that, when describing a complex symptomatol- establish the diagnosis as possible or ogy including dementia and a disturbance of probable. Akinetic mutism has been ana- consciousness, the diagnosis of “akinetic mut- tomically divided into two forms—the ism” should be waived and instead be replaced mesencephalic form and the frontal form. by the term “apallic syndrome”.2–3 Another The aim of this study was to delimit the approach is to use the term of akinetic mutism symptom of akinetic mutism in patients and to consider it as just one of several stages with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from the within a process leading to an apallic complex of symptoms of an apallic syn- syndrome.4 Akinetic mutism has been a solid drome and to assign it to the individual classification criterion for the diagnosis of pos- forms. sible and probable Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Methods—Between April and December used by the European Creutzfeldt-Jakob dis- 1996, 25 akinetic and mute patients with ease surveillance unit since 1993.