The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Side Effects of Labor Market Policies

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13846 Side Effects of Labor Market Policies Marco Caliendo Robert Mahlstedt Gerard J. van den Berg Johan Vikström NOVEMBER 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13846 Side Effects of Labor Market Policies Marco Caliendo University of Potsdam, IZA, DIW and IAB Robert Mahlstedt University of Copenhagen and IZA Gerard J. van den Berg University of Bristol, University of Groningen, IFAU, IZA, ZEW, CEPR, CESifo and UCLS Johan Vikström IFAU, Uppsala University and UCLS NOVEMBER 2020 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. -

Product List March 2019 - Page 1 of 53

Wessex has been sourcing and supplying active substances to medicine manufacturers since its incorporation in 1994. We supply from known, trusted partners working to full cGMP and with full regulatory support. Please contact us for details of the following products. Product CAS No. ( R)-2-Methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine 112022-83-0 (-) (1R) Menthyl Chloroformate 14602-86-9 (+)-Sotalol Hydrochloride 959-24-0 (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2, 3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-phenylacetic 63422-71-9 acid (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2-3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-(4- 62893-24-7 hydroxyphenyl) acetic acid (r)-(+)-α-Lipoic Acid 1200-22-2 (S)-1-(2-Chloroacetyl) pyrrolidine-2-carbonitrile 207557-35-5 1,1'-Carbonyl diimidazole 530-62-1 1,3-Cyclohexanedione 504-02-9 1-[2-amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol acetate 839705-03-2 1-[2-Amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol Hydrochloride 130198-05-9 1-[Cyano-(4-methoxyphenyl) methyl] cyclohexanol 93413-76-4 1-Chloroethyl-4-nitrophenyl carbonate 101623-69-2 2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl) acetic acid Hydrochloride 66659-20-9 2-(4-Nitrophenyl)ethanamine Hydrochloride 29968-78-3 2,4 Dichlorobenzyl Alcohol (2,4 DCBA) 1777-82-8 2,6-Dichlorophenol 87-65-0 2.6 Diamino Pyridine 136-40-3 2-Aminoheptane Sulfate 6411-75-2 2-Ethylhexanoyl Chloride 760-67-8 2-Ethylhexyl Chloroformate 24468-13-1 2-Isopropyl-4-(N-methylaminomethyl) thiazole Hydrochloride 908591-25-3 4,4,4-Trifluoro-1-(4-methylphenyl)-1,3-butane dione 720-94-5 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrothieno[3,2,c] pyridine Hydrochloride 28783-41-7 4-Chloro-N-methyl-piperidine 5570-77-4 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0224012 A1 Suvanprakorn Et Al

US 2004O224012A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0224012 A1 Suvanprakorn et al. (43) Pub. Date: Nov. 11, 2004 (54) TOPICAL APPLICATION AND METHODS Related U.S. Application Data FOR ADMINISTRATION OF ACTIVE AGENTS USING LIPOSOME MACRO-BEADS (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/264,205, filed on Oct. 3, 2002. (76) Inventors: Pichit Suvanprakorn, Bangkok (TH); (60) Provisional application No. 60/327,643, filed on Oct. Tanusin Ploysangam, Bangkok (TH); 5, 2001. Lerson Tanasugarn, Bangkok (TH); Suwalee Chandrkrachang, Bangkok Publication Classification (TH); Nardo Zaias, Miami Beach, FL (US) (51) Int. CI.7. A61K 9/127; A61K 9/14 (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 424/450; 424/489 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT Eric G. Masamori 6520 Ridgewood Drive A topical application and methods for administration of Castro Valley, CA 94.552 (US) active agents encapsulated within non-permeable macro beads to enable a wider range of delivery vehicles, to provide longer product shelf-life, to allow multiple active (21) Appl. No.: 10/864,149 agents within the composition, to allow the controlled use of the active agents, to provide protected and designable release features and to provide visual inspection for damage (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 and inconsistency. US 2004/0224012 A1 Nov. 11, 2004 TOPCAL APPLICATION AND METHODS FOR 0006 Various limitations on the shelf-life and use of ADMINISTRATION OF ACTIVE AGENTS USING liposome compounds exist due to the relatively fragile LPOSOME MACRO-BEADS nature of liposomes. Major problems encountered during liposome drug Storage in vesicular Suspension are the chemi CROSS REFERENCE TO OTHER cal alterations of the lipoSome compounds, Such as phos APPLICATIONS pholipids, cholesterols, ceramides, leading to potentially toxic degradation of the products, leakage of the drug from 0001) This application claims the benefit of U.S. -

Viewer Token: Utgzgyeiftozbgp)

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org A High-Throughput Screen Identifies DYRK1A Inhibitor ID-8 that Stimulates Human Kidney Tubular Epithelial Cell Proliferation Maria B. Monteiro,1 Susanne Ramm,1,2 Vidya Chandrasekaran,1 Sarah A. Boswell,1 Elijah J. Weber,3 Kevin A. Lidberg,3 Edward J. Kelly,3 and Vishal S. Vaidya1,2,4 1Harvard Program in Therapeutic Science, Harvard Medical School Laboratory of Systems Pharmacology, Boston, Massachusetts; 2Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; 3Department of Pharmaceutics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; and 4Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts ABSTRACT Background The death of epithelial cells in the proximal tubules is thought to be the primary cause of AKI, but epithelial cells that survive kidney injury have a remarkable ability to proliferate. Because proximal tubular epithelial cells play a predominant role in kidney regeneration after damage, a potential approach to treat AKI is to discover regenerative therapeutics capable of stimulating proliferation of these cells. Methods We conducted a high-throughput phenotypic screen using 1902 biologically active compounds to identify new molecules that promote proliferation of primary human proximal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Results The primary screen identified 129 compounds that stimulated tubular epithelial cell proliferation. A secondary screen against these compounds over a range of four doses confirmed that eight resulted in a significant increase in cell number and incorporation of the modified thymidine analog EdU (indicating actively proliferating cells), compared with control conditions. These eight compounds also stimulated tubular cell proliferation in vitro after damage induced by hypoxia, cadmium chloride, cyclosporin A, or polymyxin B. -

Drug–Drug Salt Forms of Ciprofloxacin with Diflunisal and Indoprofen

CrystEngComm View Article Online COMMUNICATION View Journal | View Issue Drug–drug salt forms of ciprofloxacin with diflunisal and indoprofen† Cite this: CrystEngComm,2014,16, 7393 Partha Pratim Bag, Soumyajit Ghosh, Hamza Khan, Ramesh Devarapalli * Received 27th March 2014, and C. Malla Reddy Accepted 12th June 2014 DOI: 10.1039/c4ce00631c www.rsc.org/crystengcomm Two salt forms of a fluoroquinolone antibacterial drug, Crystal engineering approach has been effectively ciprofloxacin (CIP), with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, utilized in recent times in the synthesis of new forms particu- diflunisal (CIP/DIF) and indoprofen (CIP/INDP/H2O), were synthe- larly by exploiting supramolecular synthons. Hence the sized and characterized by PXRD, FTIR, DSC, TGA and HSM. Crystal identification of synthons that can be transferred across Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. structure determination allowed us to study the drug–drug different systems is important. For example, synthon trans- interactions and the piperazine-based synthon (protonated ferability in cytosine and lamivudine salts was recently dem- piperazinecarboxylate) in the two forms, which is potentially useful onstrated by Desiraju and co-workers by IR spectroscopy for the crystal engineering of new salt forms of many piperazine- studies.20a Aakeröy and co-workers successfully estab- based drugs. lished the role of synthon transferability (intermolecular amide⋯amide synthons) in the assembly and organization of Multicomponent pharmaceutical forms consisting of an bidentate acetylacetonate (acac) and acetate “paddlewheel” active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and an inactive 20b complexes of a variety of metal(II)ions. Recently Das et al. co-former,whichisideallyagenerally recognized as safe – have reported the gelation behaviour in various diprimary This article is licensed under a 1 3 (GRAS) substance, have been well explored in recent times. -

PMBJP Product.Pdf

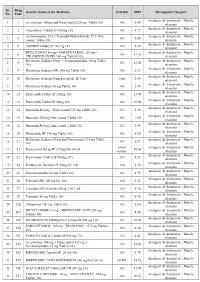

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

Summary of Product Characteristics

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT *IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10mg tablets IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20mg tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10 mg tablets Each tablet contains: Manidipine hydrochloride 10mg Excipient with known effect: 119,61 mg lactose monohydrate/tablet IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20 mg tablets Each tablet contains: Manidipine hydrochloride 20mg Excipient with known effect: 131,80 mg lactose monohydrate/tablet For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Tablet IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10mg: pale yellow, round, scored tablet; IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20mg: yellow-orange, oblong, scored tablet. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Mild to moderate essential hypertension 4.2 Posology and method of administration The recommended starting dose is 10 mg once a day. Should the antihypertensive effect be still insufficient after 2-4 weeks of treatment, it is advisable to increase the dosage to the usual maintenance dose of 20 mg once a day. Elderly In view of the slowing down of metabolism in the elderly, the recommended dose is 10mg once daily. This dosage is sufficient in most elderly patients; the risk/benefit of any dose increase should be considered with caution on an individual basis. Renal impairment In patients with mild to moderate renal dysfunction care should be taken when increasing the dosage from 10 to 20mg once a day. Hepatic impairment Due to the extensive hepatic metabolisation of manidipine, patients with mild hepatic dysfunction should not exceed 10mg once a day (see also Section 4.3 Contraindications). Tablet must be swallowed in the morning after breakfast, without chewing it, with a few liquid. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

4 Supplementary File

Supplemental Material for High-throughput screening discovers anti-fibrotic properties of Haloperidol by hindering myofibroblast activation Michael Rehman1, Simone Vodret1, Luca Braga2, Corrado Guarnaccia3, Fulvio Celsi4, Giulia Rossetti5, Valentina Martinelli2, Tiziana Battini1, Carlin Long2, Kristina Vukusic1, Tea Kocijan1, Chiara Collesi2,6, Nadja Ring1, Natasa Skoko3, Mauro Giacca2,6, Giannino Del Sal7,8, Marco Confalonieri6, Marcello Raspa9, Alessandro Marcello10, Michael P. Myers11, Sergio Crovella3, Paolo Carloni5, Serena Zacchigna1,6 1Cardiovascular Biology, 2Molecular Medicine, 3Biotechnology Development, 10Molecular Virology, and 11Protein Networks Laboratories, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), Padriciano, 34149, Trieste, Italy 4Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS "Burlo Garofolo", Trieste, Italy 5Computational Biomedicine Section, Institute of Advanced Simulation IAS-5 and Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine INM-9, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425, Jülich, Germany 6Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, University of Trieste, 34149 Trieste, Italy 7National Laboratory CIB, Area Science Park Padriciano, Trieste, 34149, Italy 8Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, 34127, Italy 9Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (IBCN), CNR-Campus International Development (EMMA- INFRAFRONTIER-IMPC), Rome, Italy This PDF file includes: Supplementary Methods Supplementary References Supplementary Figures with legends 1 – 18 Supplementary Tables with legends 1 – 5 Supplementary Movie legends 1, 2 Supplementary Methods Cell culture Primary murine fibroblasts were isolated from skin, lung, kidney and hearts of adult CD1, C57BL/6 or aSMA-RFP/COLL-EGFP mice (1) by mechanical and enzymatic tissue digestion. Briefly, tissue was chopped in small chunks that were digested using a mixture of enzymes (Miltenyi Biotec, 130- 098-305) for 1 hour at 37°C with mechanical dissociation followed by filtration through a 70 µm cell strainer and centrifugation. -

List of Vital Essential and Necessary Drugs and Medical Sundries For

LIST OF VITAL ESSENTIAL AND NECESSARY DRUGS AND 2015 MEDICAL SUNDRIES FOR PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTIONS Sixth Edition STANDARDS & REGULATION DIVISION JAMAICA List of Vital Essential and Necessary List of Drugs and Medical Sundries for Public Institutions List of Vital Essential and Necessary List of Drugs and Medical Sundries for Public Institutions CONTENTS CONTENTS Contd. Page Preface 5-6 Page Information on Hospitals and Health Centres 7 Explanatory Notes 8 Medical Sundries 69-73 Prescription Writing 9-10 Dental Supplies 74 Algorithm for Treatment of Hypertension 11-12 Radiotherapy – Diagnostic Agents 75 Algorithm for Management of Type 2 Diabetes 13-14 Raw Materials 76 List of Drugs Designated for NHF 15-17 List of Drugs Designated for JADEP 18 VOLUME11 – SPECIALIST LIST 77 VOLUME 1 – GENERAL LIST 19 CLASSIFICATION OF DRUGS SECTION 1. Cardiovascular System 78 CLASSIFICATION OF DRUGS SECTION 2. Central Nervous System 79 SECTION 1. Cardiovascular System 20-24 SECTION 3. Dermatology 80 SECTION 2. Central Nervous System 25-30 SECTION 4. Endocrine System 80 SECTION 3. Dermatology 31-33 SECTION 5. Gastro-intestinal System 81 SECTION 4. Ear, Nose and Oropharynx 34-35 SECTION 6. Infections 81 SECTION 5. Endocrine System 36-38 SECTION 7. Malignant Disease and SECTION 6. Gastro-intestinal System 39-40 Immunosuppression 82 SECTION 7. Infections 41-46 SECTION 8. Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases 83 SECTION 8. Malignant Disease and SECTION 9. Ophthalmology 83 Immunosuppression 47-49 SECTION 10. Genito-Urinary Tract Disorders 84 SECTION 9. Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases 50-51 SECTION 11. Respiratory System 84 SECTION 10. Nutrition and Blood 52-54 SECTION 12. -

Guidelines of Hypertension – 2020 Barroso Et Al

Brazilian Guidelines of Hypertension – 2020 Barroso et al. Guidelines Brazilian Guidelines of Hypertension – 2020 Development: Department of Hypertension of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology (DHA-SBC), Brazilian Society of Hypertension (SBH), Brazilian Society of Nephrology (SBN) Norms and Guidelines Council (2020-2021): Brivaldo Markman Filho, Antonio Carlos Sobral Sousa, Aurora Felice Castro Issa, Bruno Ramos Nascimento, Harry Correa Filho, Marcelo Luiz Campos Vieira Norms and Guidelines Coordinator (2020-2021): Brivaldo Markman Filho General Coordinator: Weimar Kunz Sebba Barroso Coordination Work Group: Weimar Kunz Sebba Barroso, Cibele Saad Rodrigues, Luiz Aparecido Bortolotto, Marco Antônio Mota-Gomes Guideline Authors: Weimar Kunz Sebba Barroso,1,2 Cibele Isaac Saad Rodrigues,3 Luiz Aparecido Bortolotto,4 Marco Antônio Mota-Gomes,5 Andréa Araujo Brandão,6 Audes Diógenes de Magalhães Feitosa,7,8 Carlos Alberto Machado,9 Carlos Eduardo Poli-de-Figueiredo,10 Celso Amodeo,11 Décio Mion Júnior,12 Eduardo Costa Duarte Barbosa,13 Fernando Nobre,14,15 Isabel Cristina Britto Guimarães,16 José Fernando Vilela- Martin,17 Juan Carlos Yugar-Toledo,17 Maria Eliane Campos Magalhães,18 Mário Fritsch Toros Neves,6 Paulo César Brandão Veiga Jardim,2,19 Roberto Dischinger Miranda,11 Rui Manuel dos Santos Póvoa,11 Sandra C. Fuchs,20 Alexandre Alessi,21 Alexandre Jorge Gomes de Lucena,22 Alvaro Avezum,23 Ana Luiza Lima Sousa,1,2 Andrea Pio-Abreu,24 Andrei Carvalho Sposito,25 Angela Maria Geraldo Pierin,24 Annelise Machado Gomes de Paiva,5 Antonio -

Welfare Effects of Physician-Industry Interactions: Evidence from Patent

Welfare Effects of Physician-industry Interactions: Evidence From Patent Expiration (PRELIMINARY — do not cite without permission) Aaron Chatterji∗, Matthew Grennany, Kyle Myersz, Ashley Swansony December 29, 2017 Abstract Many transactions occur via expert advisors, especially in the healthcare sector, and as such, firms frequently implement strategies to influence these advisors. The effi- ciency of these interactions is an empirical question. Using data on physician-industry interactions and prescribing behavior during the entry of a major generic statin drug, we examine the causal effect and welfare implications of the most common type of interaction: meals. Guided by a theoretical model of endogenous meals, we develop an instrumental variables identification strategy and document reduced form evidence that these meals directly influence prescribing decisions. We find a significant degree of negative selection and primarily extensive margin effects, whereby firms target small meals to prescribers with an otherwise low propensity to use the target drug. Given this evidence, we estimate a structural model of drug choice that allows us to predict counterfactual outcomes in a world where these meals are banned. Results from these counterfactuals are in line with theoretical predictions that these interactions can offset efficiency losses due to pricing with market power. However, this offset does not appear large enough to justify their existence in this particular market. ∗Duke University, The Fuqua School & NBER yUniversity of Pennsylvania, The Wharton School & NBER zNBER Please direct correspondence to [email protected]. The data used in this paper were generously provided, in part, by the Kyruus, Inc. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Wharton Dean’s Research Fund, Mack Institute, and Public Policy Initiative.