Egg Rejection Behavior and Clutch Characteristics of the European Greenfinch Introduced to New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Developing Methods for the Field Survey and Monitoring of Breeding Short-Eared Owls (Asio Flammeus) in the UK: Final Report from Pilot Fieldwork in 2006 and 2007

BTO Research Report No. 496 Developing methods for the field survey and monitoring of breeding Short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) in the UK: Final report from pilot fieldwork in 2006 and 2007 A report to Scottish Natural Heritage Ref: 14652 Authors John Calladine, Graeme Garner and Chris Wernham February 2008 BTO Scotland School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA Registered Charity No. SC039193 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF APPENDICES...........................................................................................................vi SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... viii CRYNODEB............................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................xvi 1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS...........................................................................................2 -

First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla Coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis Chloris from Lord Howe Island

83 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2004, 2I , 83- 85 First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris from Lord Howe Island GLENN FRASER 34 George Street, Horsham, Victoria 3400 Summary Details are given of the first records of two species of finch from Lord Howe Island: the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. These records, from the early 1980s, have been quoted in several papers without the details hav ing been published. My Common Chaffinch records are the first for the species in Australian territory. Details of my records and of other published records of other European finch es on Lord Howe Island are listed, and speculation is made on the origin of these finches. Introduction This paper gives details of the first records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris for Lord Howe Island. The Common Chaffinch records are the first for any Australian territory and although often quoted (e.g. Boles 1988, Hutton 1991, Christidis & Boles 1994), the details have not yet been published. Other finches, the European Goldfinch C. carduelis and Common Redpoll C. fiammea, both rarely reported from Lord Howe Island, were also recorded at about the same time. Lord Howe Island (31 °32'S, 159°06'E) lies c. 800 km north-east of Sydney, N.S.W. It is 600 km from the nearest landfall in New South Wales, and 1200 km from New Zealand. Lord Howe Island is small (only 11 km long x 2.8 km wide) and dominated by two mountains, Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower, the latter rising to 866 m above sea level. -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

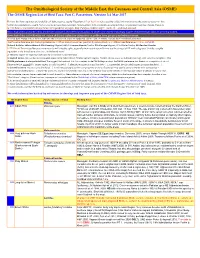

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

5 Summary of Conservation Status and Small Numbers

Technical considerations in conjunction with the proposal to apply Autumn derogation for the live-capturing of seven finch species – Chaffinch ( Fringilla coelebs ), Linnet ( Carduelis cannabina ), European Goldfinch ( Carduelis carduelis ), European Greenfinch ( Carduelis chloris ), Hawfinch ( Coccothraustes coccothrausthes ), European Serin ( Serinus serinus ) and Eurasian Siskin ( Carduelis spinus ). An analysis of the proposal presented by the Federation for Hunting and Conservation — Malta (FKNK) Wild Birds Regulation Unit Parliamentary Secretariat for Agriculture, Fisheries and Animal Rights Ministry for Sustainable Development, the Environment and Climate Change April 2014 Abbreviations BTO British Trust for Ornithology BWP Birds of the Western Palearctic FKNK The Federation for Hunting and Conservation — Malta IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature KVM Das Kompendium der Vögel Mitteleuropas WBRU Wild Birds Regulation Unit i Executive Summary On the 22 nd August 2013, the Federation for Hunting and Conservation — Malta (FKNK) submitted a proposal before Malta Ornis Committee concerning the application of a derogation under Article 9 of the EC Birds Directive to permit limited live capturing of seven species of finches under strictly supervised regime. The Committee requested the Wild Birds Regulation Unit to assess this proposal from a legal, technical and conservation point of view and to refer back its analysis for further consideration. FKNK’s proposal concerns the opening of an autumn 2014 season for the live-capturing of seven finch species, namely Chaffinch ( Fringilla coelebs ), Linnet ( Carduelis cannabina ), Goldfinch ( Carduelis carduelis ), Greenfinch (Carduelis chloris ), Hawfinch ( Coccothraustes coccothraustes ), Serin ( Serinus serinus ) and Siskin ( Carduelis spinus ) from 7 October to 7 December. This report reviews the technical and conservation issues arising out of this proposal with the aim of providing the Ornis Committee and the Government with an informed basis for further consideration and decision. -

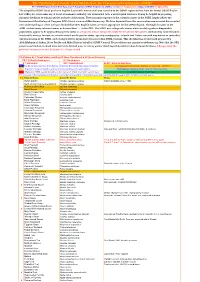

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

Not Every White Bird Is an Albino: Sense and Nonsense About Colour Aberrations in Birds

Not every white bird is an albino: sense and nonsense about colour aberrations in birds Hein van Grouw n the birding world, general confusion seems food and transformed into colour pigments by Ito exist about colour mutations in wild birds enzymes. The deposition of the pigments takes and the correct naming of these aberrations. place directly at the start of feather growth. Almost all whitish aberrations are called ‘(partial) Aberrations in this pigmentation are mostly albino’. However, most of these are not albino caused by a food problem and usually do not and ‘partial albinism’ is – by definition – not have a genetic cause. Well-known examples are even possible. Some mutations are hard to distin- flamingos Phoenicopteridae and Scarlet Ibis guish in the field (and in museum collections) Eudocimus ruber, which owe their respective because the colour of feathers with a pigment pink and red colours to the presence of red caro- reduction is easily bleached by sunlight and can tenoids in their natural food. When these carote- even become almost white. For the correct iden- noids are in short supply, these birds will appear tification and naming of colour mutations, it is white after the next moult. In the past, this hap- necessary to know which changes have occurred pened frequently in captive individuals of these in the original pigmentation. But first of all, it is species before caretakers understood this relation necessary to understand which pigments deter- between food and coloration. mine the normal colours of feathers and how In several European passerines, part of their these pigments are formed. -

Green Finches” Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 432a Idenfification of “Green Finches” Put your logo here IDENTIFICATION OF “GREEN FIN- CHES” (GENUS Chloris , Serinus , Car- duelis and Spinus ) 1 - With yellow patches on flight and tail feat- hers..……………………………...... 2 1 - Without yellow patches on flight and tail feathers ………….…………..…..... 5 2 - With yellow patches on all flight feathers 2 ….……………………….……. 3 5 - With yellow patches only on primaries 3 ……..………………….…………..... 4 3 - Crown and breast greenish-white streaked Eurasian Siskin. Fe- dark; tail feathers with yellow patches only on male: with yellow the outer webs: Eurasian Siskin, female ( Spinus patches on all flight spinus ) feathers (1); crown (2) and breast (3) - With dark crown; unstreaked yellow breast; streaked; tail feathers tail feathers with extensive yellow patches: Eu- with yellow patches rasian Siskin, male ( Spinus spinus ) only on the outer webs (4); long and 4 - The yellow patches on primaries do not 4 pointed bill (5). reach the shafts; outer tail feathers with yellow patches only on inner webs; unstreaked greenish -grey breast: European Greenfinch, female (Chloris chloris ) - The yellow patches on primaries reach the shafts; outer tail feathers with extensive yellow patches; unstreaked greenish breast: European Greenfinch, male ( Chloris chloris ) 1 - With wings and tail similar to those des- cribed but with streaked breast: European Greenfinch, juvenile ( Chloris chloris ) 2 5 - With unstreaked breast and flanks: Citril Finch, adult ( Carduelis citrinella ) 5 3 - With streaks on breast and/or flanks …. 6 6 - With unstreaked breast and streaked flanks: European serin, male ( Serinus serinus ) Eurasian Siskin. Male: with yellow patches on - With streaks on breast and flanks ..…….7 all flight feathers (1); dark crown (2); 7 - Breast bolding streaked dark; with short and unstreaked yellow stubby bill: European serin, female/juvenile breast (3); tail feathers (Serinus serinus ) with extensive yellow patches (4); long and pointed bill (5). -

Arabian Peninsula

THE CONSERVATION STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE BREEDING BIRDS OF THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Compiled by Andy Symes, Joe Taylor, David Mallon, Richard Porter, Chenay Simms and Kevin Budd ARABIAN PENINSULA The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM - Regional Assessment About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature-based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with almost 1,300 government and NGO Members and more than 15,000 volunteer experts in 185 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by almost 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of around 7,500 experts. SSC advises IUCN and its members on the wide range of technical and scientific aspects of species conservation, and is dedicated to securing a future for biodiversity. SSC has significant input into the international agreements dealing with biodiversity conservation. About BirdLife International BirdLife International is the world’s largest nature conservation Partnership. BirdLife is widely recognised as the world leader in bird conservation. -

Tropical Birding Israel Tour

Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 Tropical Birding Israel Tour March 10– 22, 2018 TOUR LEADER: Trevor Ellery Report and photos Trevor Ellery, all photos are from the tour. Green Bee-eater. One of the iconic birds of southern Israel. This was Tropical Birding’s inaugural Israel tour but guide Trevor Ellery had previously lived, birded and guided there between 1998 and 2001, so it was something of a trip down memory lane for the guide! While Israel frequently makes the international news due to ongoing tensions within the country, such problems are generally concentrated around specific flashpoints and much of the rest of the country is calm, peaceful, clean and modern. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 Our tour started on the afternoon of the 10th where, after picking up the group at Ben Gurion airport near Tel Aviv, we headed north along the coastal strip, collecting our local guide (excellent Israeli birder Chen Rozen) and arrived at Kibbutz Nasholim on the shores of the Mediterranean with plenty of time for some local birding in the nearby fishponds. Spur-winged Lapwing – an abundant, aggressive but nevertheless handsome species wherever we went in Israel. Hoopoe, a common resident, summer migrant and winter visitor. We saw this species on numerous days during the tour but probably most interesting were quite a few birds seen clearly in active migration, crossing the desolate deserts of the south. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 We soon managed to rack up a good list of the commoner species of these habitats.