004; Hyunyoung 2007) Exploring the Link Between Framing and Ideology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Frgs) (Amendment Year 2021)

DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION GUIDELINES OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH GRANT SCHEME (FRGS) (AMENDMENT YEAR 2021) BAHAGIAN KECEMERLANGAN PENYELIDIKAN IPT JABATAN PENDIDIKAN TINGGI KEMENTERIAN PENGAJIAN TINGGI ARAS 7, NO. 2, MENARA 2 JALAN P5/6, PRESINT 5 62200 PUTRAJAYA TEL. NO.: 03-8870 6974/6975 FAX NO.: 03-8870 6867 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision and Mission of Fundamental Research 3 PART 1 (INTRODUCTION) 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Philosophy 4 1.3 Definition 4 1.4 Purpose 4 PART 2 (APPLICATION) 2.1 General terms of application 5 2.2 Research priority areas 6 2.3 Research duration 8 2.4 Ceiling of fund 8 2.5 Research output 9 2.6 Application rules 10 PART 3 (ASSESSMENT) 3.1 Application assessment 11 3.2 Assessment criteria 12 PART 4 (MONITORING) 4.1 Research implementation 13 4.2 Monitoring 13 PART 5 (FINANCIAL REGULATIONS) 5.1 Expenditure codes 15 5.2 Use of provisions 16 PART 6 (RESULTS) 6.1 Result announcement and fund distribution 18 6.2 Agreement document and contract 18 APPENDICES 19 Application Flow Chart Monitoring Flow Chart Scheduled Monitoring Cycle List of Higher Education Institutions (Appendix A) 2 VISION AND MISSION OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH Vision Competitive fundamental research for knowledge transformation and national excellence. Mission Cultivate, empower and preserve high impact research capacity to generate knowledge that can contribute to talent development, intellectual growth, new technology invention and dynamic civilization. 3 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Amendment Year 2021 document is prepared as a reference and guide for application of research grant under the Department of Higher Education (JPT), Ministry of Higher Education (KPT). -

Your Gateway to Malaysia International Student Guide Your Next Study Destination

Your Gateway to Malaysia International Student Guide Your next study destination. 2 INTERNATIONAL STUDENT GUIDE UOW MALAYSIA KDU 3 5+ stars rating university CONTENTS Where QS World University Rankings 2021 WHERE DOORS OPEN 4 — doors open MALAYSIA 6 Top 1% MALAYSIA AT A GLANCE 7 We’re here to open doors and University of Wollongong Australia THE HEART OF SOUTHEAST ASIA 8 ranking among the world’s support your choices while giving universities. MALAYSIA CULTURE 9 196th in the world – QS World University NATIONAL CELEBRATION you the freedom and resources to Rankings 2021 10 chase your dream career. TOP 10 MOST COLOURFUL FESTIVALS IN 11 — MALAYSIA MUST VISIT PLACES IN MALAYSIA 12 KUALA LUMPUR 14 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS 15 TOP 5 GREAT MALAYSIAN DISHES 16 TOP 5 MOST INSTAGRAMMABLE CAFES 17 PENANG 18 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS 19 WHERE TO EAT IN PENANG 20 5 BEST STREET FOOD IN PENANG 21 UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGGONG Top 20 A TRULY GLOBAL UNIVERSITY 24 16th best modern university in the world. GLOBAL CAMPUSES 25 QS Top 50 Under 50 Rankings 2020 WHY STUDY IN MALAYSIA 26 — UOW MALAYSIA KDU 28 UOW MALAYSIA KDU CAMPUSES 29 From here to Top 200 ACADEMIC SCHOOLS 30 Rating for UOW graduates by global GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES 36 employers. every corner INDUSTRY PARTNERS 37 QS Graduate Employability Rankings 2020 CAMPUS FACILITIES 38 — UOW ACCOMMODATION 40 A globally recognised and respected INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE 42 degree from UOW is your passport Top 250 PARTNER UNIVERSITIES 43 to a world of opportunity. Ranking among the world’s best universities. 212th in the world – QS World University Rankings 2020, 201-250 band – Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2020, 220th – Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) 2019 — 4 INTERNATIONAL STUDENT GUIDE UOW MALAYSIA KDU 5 Truly Asia Malaysia Situated in the midst of the Asia Pacific region, Malaysia enjoys a strategic location and a year-round tropical climate. -

Final Program Book Is Available for Download

Welcome Message from the Vice Chancellor, Universiti Sains Malaysia 2 Welcome Message from the Dean, School of Management 3 Welcome Message from the President, Malaysian Finance Association 4 Welcome Message from the Chair of the Confernece, MFAIC2021 5 About the Organizers 6 Keynote Address 7 Plenary Speakers & Networking with Editor Session 8 Networking with Editor Session 9 Awards 10 Publication Opportunity 11 Organising Committee 12 Acknowledgement to Sponsors 13 Conference Programme 14 Session Tabulation, Session Chair, Host & Assess Key 15 Pre-Conference PhD Colloquium 16 Conference Presentation By Platform: Platform A 17 Conference Presentation By Platform: Platform B 21 Conference Presentation By Platform: Platform C 25 Conference Presentation By Platform: Platform D 29 List of Abstract By Platform: Platform A 33 List of Abstract By Platform: Platform B 46 List of Abstract By Platform: Platform C 57 List of Abstract By Platform: Platform D 67 List of Paper Reviewers 79 List of Presenters 81 List of Participants 84 Presentation Guidelines 87 23rd MFA International Conference, 3rd - 5th August 2021 23rd MFA International Conference, 3rd - 5th August 2021 2 23rd MFA International Conference, 3rd - 5th August 2021 On behalf of the Malaysian Finance Association and Universiti Sains Malaysia, I would like to welcome all delegates to the 23rd MFA Conference themed, “Sustainability of business and finance: Embracing the new norms amidst Covid 19”. The relationship between The Malaysian Finance Association and the School of Management is crucial in shaping the academic knowledge and fostering new boundaries in the context of Malaysia’s economy as well as the emerging markets. As one of the management schools in Malaysia, we fully support the objectives and endeavours of MFA. -

Study a Postgraduate Degree at UOW Malaysia

Postgraduate Studies 2021 Study a postgraduate degree at 5-Star rating For Learner Engagement 2020 Good Universities Guide UOW Top 20 14th best modern university in the world QS Top 50 Under 50 Rankings 2020 POSTGRADUATE STUDIES 2021 STUDIES POSTGRADUATE Malaysia Top 1% Rating for graduates KDU 2020 QS Graduate Employability Rankings Top 200 Universities in the world QS World University Rankings 2020 2 STUDY A POSTGRADUATE DEGREE AT UOW 2 MALAYSIA KDU CHANGE THAT MATTERS 4 POSTGRADUATE STUDIES 6 ACCREDITATION OF PRIOR EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING 7 (APEL) HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT FUND (HRDF) 7 POSTGRADUATE DEGREE OPTIONS 8 UOW MALAYSIA KDU 10 STUDY ROUTE 11 COURSE STRUCTURES BY COURSEWORK BUSINESS POSTGRADUATE CERTIFICATE IN BUSINESS 12 ADMINISTRATION POSTGRADUATE DIPLOMA IN ENTERPRISE RISK 13 The world is changing. Fast. MANAGEMENT Rising to the challenge of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (MBA) 14 postgraduate study is one COMMUNICATION & CREATIVE ARTS KDU MALAYSIA UOW way to stay ahead. MASTER OF ARTS (COMMUNICATION MANAGEMENT) 16 MASTER OF DESIGN (INNOVATION) 17 As economic, technological COURSE STRUCTURES BY RESEARCH and social forces transform BUSINESS the way we work, gaining up- MASTER OF ARTS (BY RESEARCH) 18 MASTER OF BUSINESS 19 to-date skills and knowledge DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BUSINESS) 20 can elevate you into new COMPUTING opportunities in the global MASTER IN COMPUTER SCIENCE 22 job market. DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (COMPUTER SCIENCE) 23 ENGINEERING Postgraduate study can help MASTER OF SCIENCE (BY RESEARCH) 24 you achieve a better salary, MASTER OF SCIENCE (ENGINEERING) 25 accelerate your current DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (ENGINEERING) 26 career or start a new one. So HOSPITALITY, TOURISM & CULINARY ARTS MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM 27 find your specialty and make DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (HOSPITALITY AND 28 your mark – on a person, a TOURISM) SOCIAL SCIENCE business, a community or MASTER OF ART (SOCIAL SCIENCE) 29 maybe even the world. -

Undergraduate Guide — 2021

Undergraduate Guide — 2021 Stand for purpose Start here. Stop at nothing. UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG UNIVERSITY Your time at UOW is about uncovering your CONTENTS passions and using them to make an impact. WHERE DOORS OPEN 2 CHANGE THAT MATTERS 4 As the world rapidly changes, the career WOLLONGONG 6 ahead of you may not yet exist. The YOUR FUTURE, YOUR WAY 8 technologies you’ll depend on may still CAMPUSES WOLLONGONG CAMPUS 10 UNDERGRADUATE GUIDE 2021 UNDERGRADUATE need to be invented. To help you become REGIONAL AND METRO 12 future ready, UOW focuses on teaching CAMPUSES not just specialist knowledge, but also the GLOBAL CAMPUSES 14 skills needed to embrace change and solve STUDY ABROAD 16 tomorrow’s challenges. COURSES COURSE INDEX 18 DOUBLE DEGREES 24 “I wasn’t really looking at other unis. HOW TO READ THIS GUIDE 25 I had been to so many UOW activity DEGREES 26 days throughout school and I always ENTRY PATHWAYS liked the atmosphere on campus. ADMISSION TO UOW 86 I loved all the greenery compared HIGH ACHIEVER OPTIONS 90 to the high rises you get in the city. NON-SCHOOL LEAVERS 92 When I got my offer, it felt like a UOW COLLEGE 94 weight lifted off my shoulders to ACCOMMODATION 96 know it was all there, ready for me COSTS 98 after the HSC.” IMPORTANT DATES 99 SPORTS PROGRAMS 100 OLIVIA EARLY ADMISSION 101 FOURTH YEAR STUDENT BACHELOR OF SCIENCE (HONOURS) 1 At UOW, we're big enough to matter, but small enough to care. You’ll receive all the support and resources you need to find your purpose and chase your dream career. -

Download Fair Directory

UTP-Sureworks-Directory-V5.pdf 1 13/11/2019 5:02:57 PM C M Y CM MY A CY CMY K 2019_ad_A-Levels_A5_Dec.indd 2 19/11/2019 3:09 PM Inside this fair directory MESSAGE CONTENTS ADVERTISERS in this directory 5 Welcome Message MESSAGE FROM 6-7 Which Pre-U Programme Should DATIN JERCY CHOO You Pursue? ACCA (The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants) 15 A Closer Look at Veterinary Science FROM SUREWORKS 12-13 AIMST University 14 Organiser of the Education & Further Studies Fair, Dec 2019 What is Automotive Engineering? Asia Pacific University 26 16-17 Curtin University 19 Skills to Prepare You for the Falcon Universal 10 20-21 Fourth Industrial Revolution HELP University IFC Kolej Yayasan UEM (KYUEM) 8 Welcome to the Education & Datin Jercy Choo 22-23 What are Green Jobs? Manipal International University CPS Further Studies Fair Series 50! Medic Ed Consultant Sdn Bhd IBC 28-29 Careers in Event Management Methodist College Kuala Lumpur OBC If you are currently searching for the next step to take in your education journey, you are in the Monash University Malaysia 18 right place! Find all the information you need right here at the fair over the weekend. As there are 32-33 Careers in Sports Science MyStudy Education Consulting so many education options available today, it is important to do as much research as possible to Sdn Bhd (Study Abroad) 35 ultimately choose the right course for you. 36-37 Jobs to Expect in 2020 New Era University College 27 Newcastle University The fair features leading universities, colleges, and skills-based institutions in Malaysia and abroad. -

Detailed Table of Contents

Detailed Table of Contents Preface.................................................................................................................................................xix Acknowledgment.............................................................................................................................xxvii Introduction....................................................................................................................................xxviii Chapter 1 UnderstandingCustomerEngagementandPurchaseBehaviorinAutomobiles:TheRoleof DigitalTechnology................................................................................................................................. 1 Krishnadas R., SASTRA University, India Withrapidtechnologicalinnovation,customerexpectationsareevolvingatafasterpace.Technologyplays .avitalroleinthevaluecreationbykindlingopportunitiesthroughtransmutingconsumptionlandscape Digitaltechnologyactsasapowerfultoolforbringingoutthetransformationacrossvarioussectors .includingtheautomobileindustryaugmentedbytheexpectationsofthenewgenerationcustomers Withthebeginningoftheonlinerevolutionintheautomobilesector,shoppershavestartedtorelyon onlineplatforms.OEMsanddealersneedtheirstrongpresenceacrossOmnichannelstobattleoutthe competitionandhavetofocusonthedigital-savvyshopperstofostersales.Hence,autoretailershave toexploreandexperimentwithdifferentplatformsthatofferaflexibleconsumption-basedmodelwith -

Social Media Monitoring Dashboard for University by Dicken Tan

SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN REPORT STATUS DECLARATION FORM Title: SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY Academic Session: JAN 2020 I DICKEN TAN (CAPITAL LETTER) declare that I allow this Final Year Project Report to be kept in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman Library subject to the regulations as follows: 1. The dissertation is a property of the Library. 2. The Library is allowed to make copies of this dissertation for academic purposes. Verified by, _________________________ _________________________ (Author’s signature) (Supervisor’s signature) Address: 146, JALAN PASIR PUTEH 31650 IPOH DR. PRADEEP ISAWASAN PERAK (Supervisor’s name) Date: 24 APRIL 2020 Date: 24 APRIL 2020 TITLE PAGE SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this report entitled “SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY” is my own work except as cited in the references. The report has not been accepted for any degree and is not being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signature : _________________________ Name : DICKEN TAN Date : 24 APRIL 2020 BCS (Hons) Computer Science Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus), UTAR. -

Undergraduate Handbook 2021

UOW MALAYSIA KDU COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE HANDBOOK 2021 UPDATED AS OF 27TH JANUARY 2021 1 UOW MALAYSIA KDU COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE HANDBOOK 2021 CONTENT UOW MALAYSIA KDU Foreword 4 Vision 5 Mission 5 Core Values 5 Graduate Attributes 6 The Campus 6 2021 Academic Calendar 7 ADMISSION Entry Requirements 9 Language Requirements 10 International Office 11 Fees 11 Financial Support 12 PROGRAMS & CLASSES Duration of Studies 13 Course Registration 13 COMMENCEMENT OF CLASSES Classroom Conduct 16 Attendance Requirement 16 Course Structure & Components 16 Change of Program 17 Deferment of Studies 17 Withdrawal Policy 18 ASSESSMENT & EXAMINATION Final Examination Rules & Regulations 19 Examination Conduct 20 Academic Misconduct: Plagiarism & 22 Cheating Absenteeism & Referral 23 RESULTS & GRADING SCHEME Passing Marks & Grading Scheme 24 Credit Transfer and Exemptions 26 40% Rule for Final Examination / 27 Assessment Supplementary Assessment 27 Retake 28 Appeals and Re-evaluation Process 28 PROGRESSION & AWARDS Semester Results 29 Probation Period 29 Prizes & Awards 29 Awards During Studies 29 Awards Upon Graduation 30 UPDATED AS OF 27TH JANUARY 2021 2 UOW MALAYSIA KDU COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE HANDBOOK 2021 ACADEMIC TRANSCRIPT & CERTIFICATE 31 CONVOCATION Graduation and Academic Parchment 33 Academic Dress 33 STUDENT SUPPORT School 34 Teaching & Learning Centre (TLC) 34 Library & Academic Resources 34 Computer Lab 35 STUDENT & ALUMNI CENTRE Student Experience 36 Student Well-being 36 Global Career Development 37 Accommodation & Logistic 37 Emergency Contact -

Dual Award Program University of Lincoln, UK

Dual Award Program University of Lincoln, UK Study route Penang Doctor of Philosophy Master Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Business Management [ 3 years ] Bachelor of Accountancy (Hons) [ 3½ years ] Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Media Production [ 3 years and 3 months ] Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Public Relations [ 3 years and 3 months ] Bachelor of Computer Science (Hons) [ 3 years ] Bachelor of Information Systems (Hons) [ 3 years ] Bachelor of Computer Science (Hons) in Computer & Network Technology [ 3 years ] Bachelor of Science (Hons) Mechatronics Engineering [ 3 years ] Diploma UOW Malaysia KDU Foundation Program* [ 1 year ] / STPM / Cambridge A Levels / UEC or Equivalent SPM / O Levels Or Equivalent * Specific foundation programs that meet the entry requirement. For all Postgraduates programs, kindly refer to Postgraduates Brochure or website for more information. The UOW Malaysia KDU, part of the University of Wollongong Australia Global Network, attempts to ensure the information contained in this publication is correct at the time of publication (January 2021); however, sections may be amended without notice by the institute in response to changing circumstances or for any other reason. Check with the institute at the time of application/enrolment for any updated information. uowmkdu.edu.my [email protected] uowmkdu UOW Malaysia KDU COURSE GUIDE 2021 | DUAL AWARD PROGRAM – UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN, UK Business N/345/6/0996(11/21) MQA/FA 8388 Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Business Management Intakes: COURSE STRUCTURE MPU January, May and -

Ringkasan Perakuan Dokumen Akademik

RINGKASAN PERAKUAN DOKUMEN AKADEMIK MESYUARAT JAWATANKUASA AKREDITASI BILANGAN 7 TAHUN 2021 AGENSI KELAYAKAN MALAYSIA TARIKH: 27 JULAI 2021 (SELASA) BIDANG SASTERA (SUBBIDANG SASTERA DAN KEMANUSIAAN) BIL. NAMA PROGRAM TOLAK AKREDITASI PENUH - TOLAK AKREDITASI SEMENTARA - BATAL AKREDITASI PENUH - KEKAL AKREDITASI PENUH - LULUS AKREDITASI PENUH 1. BA (Hons) Early Years Education 3+0 in collaboration with University of Greenwich, UK (MQA/FA 11187) Kolej SEGi Kuala Lumpur 2. Bachelor of Early Childhood Education (Honours) (MQA/FA 9376) Widad University College 3. Bachelor of Education (Honours) (Information Technology and Multimedia) (MQA/FA 8001) Southern University College 4. Master of Arts (Communication Management) (MQA/FA 9070) UOW Malaysia KDU University College 5. Sarjana Muda Psikologi dengan Kepujian (MQA/FA 5563) Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) 6. Diploma in Media Studies (MQA/FA 11210) Kolej Oneworld Hanxin 7. Ijazah Sarjana Pengajian Islam (MQA/FA 9683) Kolej Universiti Islam Melaka (KUIM) | KEPUTUSAN MJA BILANGAN 7 TAHUN 2021 (27 JUL 2021) BIDANG SASTERA (BASK) / UNIT KEURUSETIAAN (Tarikh kemaskini: 28 Jul 2021) 1 BIL. NAMA PROGRAM 8. Doktor Falsafah Pengajian Islam (Dakwah) (MQA/FA 5009) Kolej Universiti Islam Melaka (KUIM) 9. Master of Science in Technology – Integrated Language Studies (MQA/FA 9314) Universiti Malaysia Pahang (UMP) 10. Ijazah Sarjana Muda Dakwah Islamiah dengan Kepujian (MQA/FA 9140) Kolej Universiti Islam Pahang Sultan Ahmad Shah (KUIPSAS) 11. Master in Education Management (MQA/FA 11617-01) Universiti Antarabangsa INTI 12. Diploma in Interactive New Media (MQA/FA 11722) Kolej Sunway (Kuala Lumpur) LULUS AKREDITASI SEMENTARA 1. Diploma in Early Childhood Education (MQA/PA 14967) Kolej Mutiara 2. Diploma in Early Childhood Education (MQA/PA 14827) Kolej Integrasi Perkembangan Kemahiran (IPK) 3. -

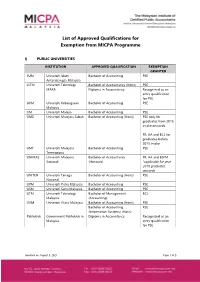

List of Approved Qualifications for Exemption from MICPA Programme

List of Approved Qualifications for Exemption from MICPA Programme I) PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES INSTITUTION APPROVED QUALIFICATION EXEMPTION GRANTED IIUM Universiti Islam Bachelor of Accounting PSE Antarabangsa Malaysia UiTM Universiti Teknologi Bachelor of Accountancy (Hons) PSE MARA Diploma in Accountancy Recognized as an entry qualification for PSE. UKM Universiti Kebangsaan Bachelor of Accounting PSE Malaysia UM Universiti Malaya Bachelor of Accounting PSE UMS Universiti Malaysia Sabah Bachelor of Accounting (Hons) PSE only for graduates from 2015 intake onwards. FR, AA and BCL for graduates before 2015 intake. UMT Universiti Malaysia Bachelor of Accounting PSE Terengganu UNIMAS Universiti Malaysia Bachelor of Accountancy FR, AA and BSFM Sarawak (Honours) *applicable for year 2018 graduates onwards UNITEN Universiti Tenaga Bachelor of Accounting (Hons) PSE Nasional UPM Universiti Putra Malaysia Bachelor of Accounting PSE USM Universiti Sains Malaysia Bachelor of Accounting PSE UTM Universiti Teknologi Bachelor of Management BCL Malaysia (Accounting) UUM Universiti Utara Malaysia Bachelor of Accounting (Hons) PSE Bachelor of Accounting PSE (Information Systems) (Hons) Politeknik Government Politeknik in Diploma in Accountancy Recognized as an Malaysia entry qualification for PSE. Updated on August 3, 2021 Page 1 of 5 II) PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES INSTITUTION APPROVED QUALIFICATION EXEMPTION GRANTED Curtin Curtin University of Bachelor of Commerce PSE Technology Sarawak (Accounting) Campus IUKL Kuala Lumpur Bachelor of Accountancy (Hons) BCL Infrastructure University College MMU Universiti Multimedia Bachelor of Accounting (Hons) PSE Monash Monash University Bachelor of Business & Commerce PSE Malaysia Campus (Accounting) Bachelor of Commerce PSE (Accounting) Sunway Sunway University Bachelor of Science (Hons) PSE Accounting and Finance *graduates must have completed ACC3054 Advanced Financial Accounting; ACC3044 Advanced Audit & Assurance; & ACC3024 Advanced Taxation.