Hunting for Sustainability: a Summary of Research Findings from Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunting in SWEDEN

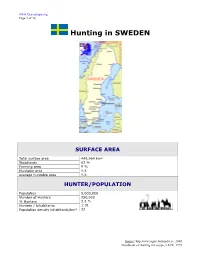

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Europe's Huntable Birds a Review of Status and Conservation Priorities

FACE - EUROPEAN FEDERATIONEurope’s FOR Huntable HUNTING Birds A Review AND CONSERVATIONof Status and Conservation Priorities Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities December 2020 1 European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE) Established in 1977, FACE represents the interests of Europe’s 7 million hunters, as an international non-profit-making non-governmental organisation. Its members are comprised of the national hunters’ associations from 37 European countries including the EU-27. FACE upholds the principle of sustainable use and in this regard its members have a deep interest in the conservation and improvement of the quality of the European environment. See: www.face.eu Reference Sibille S., Griffin, C. and Scallan, D. (2020) Europe’s Huntable Birds: A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities. European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE). https://www.face.eu/ 2 Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities Executive summary Context Non-Annex species show the highest proportion of ‘secure’ status and the lowest of ‘threatened’ status. Taking all wild birds into account, The EU State of Nature report (2020) provides results of the national the situation has deteriorated from the 2008-2012 to the 2013-2018 reporting under the Birds and Habitats directives (2013 to 2018), and a assessments. wider assessment of Europe’s biodiversity. For FACE, the findings are of key importance as they provide a timely health check on the status of In the State of Nature report (2020), ‘agriculture’ is the most frequently huntable birds listed in Annex II of the Birds Directive. -

Black Grouse:Black Grouse 14/8/07 14:56 Page 1

Black Grouse:Black Grouse 14/8/07 14:56 Page 1 Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) The black grouse has experienced a serious decline over the last century. Restoring a healthy mosaic of habitats is crucial for the recovery of this attractive bird. Worldwide distribution The black grouse is found throughout northern Eurasia from Drainage of bogs (which are important foraging grounds for Great Britain to south-eastern Siberia. The most southerly chicks) has contributed to the decline, while commercial populations are found in Kyrgyzstan and North Korea, with the afforestation has shaded out important berry plants such as northern extent of its range being northern Norway. In western blaeberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) . High tensile deer fences pose and central Europe its population is highly fragmented: a serious hazard to black grouse: when alarmed, these birds populations are very small and isolated in a number of tend to fly fairly low, and seek refuge in nearby trees. They countries and it no longer breeds in Denmark. Its overall often do not see fences in time and are killed as they hit them. population has declined, particularly in Europe, although its Furthermore, illegal shooting during the breeding season can population is more stable in its Russian stronghold. Black affect both population and breeding success. Climate further grouse usually require a mosaic of habitats, ideally including complicates the picture, as cold, wet weather in June and July heath and bog along with open woodland and scrub for cover. has increased mortality among newly-hatched chicks, which There are thought to be seven or eight subspecies of black are unable to regulate their own body temperature and are grouse, the only geographically isolated one being the most therefore vulnerable to poor weather. -

304 Isaev Layout 1

CHANGE IN PTARMIGAN NUMBERS IN YAKUTIA ARKADY P. ISAEV Institute for Biological Problems of the Cryolithozone, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, pr. Lewina 41, Yakutsk 677007, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Counts of Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) and Rock Ptarmigan (L. muta) have been conducted for as long as 25 years in some areas of the Russian Republic of Yakutia in tundra, taiga, and along the ecotone of these landscapes. The largest counts of Willow Ptarmigan occur in the tundra and forest-tundra. Willow Ptarmigan numbers fluctuate, and the length of the “cycles” vary among areas in Yakutia. Fluctuations in ptarmigan numbers are greater in the tundra and forest-tundra than in the northern taiga. Rock Ptarmigan are common in the mountain areas and tundra of Yakutia, and their numbers also fluctuate. Factors affecting ptarmigan populations are weather shifts in early spring and unfavorable weather during hatching. A decrease in the num- ber of Willow Ptarmigan in the taiga belt of Yakutia is most likely explained by a greater anthro- pogenic load. Current Willow and Rock Ptarmigan populations in Yakutia appear stable, except for central and southern areas. Received 1 February 2011, accepted 31 May 2011. ISAEV, A. P. 2011. Change in ptarmigan number in Yakutia. Pages 259–266 in R. T. Watson, T. J. Cade, M. Fuller, G. Hunt, and E. Potapov (Eds.). Gyrfalcons and Ptarmigan in a Changing World, Volume II. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA. http://dx.doi.org/10.4080/gpcw.2011.0304 Key words: Willow Ptarmigan, Rock Ptarmigan, Yakutia, Russia, count changes. -

An Overview to Population Status and Conservation of Black Grouse Worldwide (*) by Ilse STORCH 1

Cahiers d’Ethologie, 2000, 20 (2-3-4) : 153-164 An Overview to Population Status and Conservation of Black Grouse Worldwide (*) by Ilse STORCH 1 Key words : Tetrao tetrix, Black Grouse, Worldwide, population status, population conservation, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Asia . SUMMARY A worldwide overview to the status and population trend of the black grouse and to the threats to its survival is provided based on questionnaire data compiled in preparation of the IUCN Grouse Action Plan (Storch 2000). Information from most of the 29 countries within the range of the black grouse was analysed in relation to geographic distribution and frequency. Globally, the black grouse is not threatened (IUCN 1996). At the southern edge of the range and in densely populated regions, i.e., in Europe south of the boreal forest, however, black grouse are red-listed in most countries. Habitat degradation and fragmentation due to human land use activities, small population size, and increasing predator numbers are globally considered the major threats to population viability. Additional threats such as human disturbance (mostly western Europe) and exploitation (mostly eastern Europe and Asia) are regionally felt to be critical. In temperate Europe, small population sizes and isolation appear to significantly limit the chances for black grouse survival and recovery. Because the various regulating factors act in concert, influence each other, and are of locally different weight, comparative approaches from a global or at least regional perspective are recommended in black grouse conservation. (*) Communication presented at the European meeting devoted to the Fate of Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) in European Moors and Heathlands, Liège, Belgium, 26-29th September 2000 1 Wildlife Research and Management Unit, Technische Universität München, & Munich Wildlife Society, Linderhof 2, D-82488 Ettal, Germany, [email protected] 153 14 I. -

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: United Kingdom

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: United Kingdom Updated in October 2016 HUNTING AND TRAPPING LEGISLATION/ RESOURCES Name of main legislation: In the UK hunting law is a national issue, therefore several hunting laws exist: Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 for England, Scotland and Wales; Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 Year of publication: see above Supporting legislation: Legislation updates: In England and Wales the law has been amended by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 and in Scotland by the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. Hunting legislation (web link): http://www.legislation.gov.uk/browse Authority in charge of controlling hunting (web link): Home Office (Police) UK National Wildlife Crime Unit http://www.nwcu.police.uk/ Major inconsistencies or loopholes detected (if yes please describe): The UK lacks a system of licensing for hunting, with no statutory limits applied to hunting bags, or statutory requirement to submit returns. Questions have been raised about consequences for the UK’s compliance with principles under Article 7 of the Birds Directive, including “wise use”, “ecologically balanced control” and requirement not to “jeopardise conservation efforts” for huntable or non- huntable species. The lack of a licensing system also limits the capacity of authorities to apply restrictions on hunting in response to incidents of wildlife crime. Note: the devolved Scottish Government have commissioned a review of game licensing systems in Europe, which is expected to report this year. Derogations (on EU Birds Directive and/or Bern Convention): None HUNTING AND TRAPPING: METHODS AND RESTRICTIONS Legal methods/restrictions Notes - Certain game bird species can be hunt during the open shooting season (see below) - There is no requirement to hold a hunting licence. -

Checklist of the Birds of the Mainland Fife Recording Area (5Th Edition)

Checklist of the birds of the mainland Fife recording area (5th Edition) Includes all accepted records to the end of September 2014 Status RB resident breeder rb scarce or irregular resident breeder fb feral breeding population SB common summer (migrant) breeder sb scarce or irregular summer (migrant) breeder NB regular non-breeding visitor nb scarce or irregular non-breeding visitor PM common passage migrant pm scarce passage migrant (annual in small numbers) Rpm rare passage migrant (not quite annual in last 10 years) (s) denotes passage (predominantly in spring) (a) denotes passage (predominantly in autumn) WV regular winter visitor wv scarce winter visitor (annual but in small numbers) Rwv rare or irregular winter visitor X previous population now believed to be extinct in Fife (with year of last record in brackets) Int sightings almost certainly include individuals from species re-introduction schemes (e.g. Red Kite, White-tailed Eagle) SV scarce vagrant – several records per decade V vagrant – recorded very infrequently <1950 number of individual birds recorded pre-1950 >1950 number of individual birds recorded since 1950 Last Year last year of occurrence Allocation of status is generally based on the main seasonal pattern and level of occurrence of each species in the last ten years. Allocation of status for a species as a rare passage migrant, scarce vagrant or vagrant is based on the number of formally accepted records where the respective species are deemed to be BBRC, SBRC or FLRC description species. Species Breeding Status -

Condition-Dependence, Colouration and Growth of Red Eye Combs in Black Grouse Lyrurus Tetrix

Condition-dependence, colouration and growth of red eye combs in black grouse Lyrurus tetrix Sarah Harris A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Masters of Science by research, supervised by Dr. Carl Soulsbury and Dr. Tom Pike This research programme was carried out in collaboration with the University of Jyväskylä, Finland February 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables .......................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Thesis Outline ................................................................................................................................ 8 Contributions ............................................................................................................................ 8 Publications and Conferences ............................................................................................... 9 Ethics ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 11 1.1 Sexual ornament expression ......................................................................................... 11 1.3 Research aims ................................................................................................................ -

A Review of Management Prescriptions for Black Grouse Tetrao Tetrix in Britain: an Update and Revision

A Review of Management Prescriptions for Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in Britain: An update and revision Original report - A review of Management Prescriptions Advocated for Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in the UK: An update and revision by John Calladine, 20 December 2002. Revised version updated by Andy Cole, Chris Bailey1, Robert Hawkes, James Gordon, Adam Fraser, Yvonne Boles, Mark O’Brien & Murray Grant, 25 August 2012. 1Chris Bailey, 2 Lochside View, Edinburgh Park, Edinburgh EH12 9DH 1 A Review of Management Prescriptions for Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in Britain: An update and revision Contents 1. Background and report structure 2. A summary of management prescriptions, targeting strategies and monitoring advocated for black grouse. 3. Monitoring of population density and breeding success 3.1 Monitoring black grouse populations 3.2 Monitoring breeding success 4. Monitoring of some factors of importance in affecting black grouse demography 4.1 Fence and other wire strikes 4.2 Monitoring of grazing animals 4.3 Monitoring of habitat and habitat changes 4.4 Monitoring of predators 5. Scale of management 5.1 Lek scale or Patch scale 5.2 Brood scale 5.3 Winter home-range scale 5.4 Regional or metapopulation scale 5.4.1 Habitat fragmentation 5.4.2 Dispersal 5.5 Temporal scale 6. Targeting management 7. Management prescriptions 7.1 Trees, shrubs and woodland 7.1.1 Larger woodlands (generally over 200 hectares) 7.1.2 Small woodland (generally under 10 hectares) 7.1.3 Edge restructuring 7.2 Ground vegetation 7.2.1 Nesting and brood-rearing habitats 7.2.2 Ericaceous vegetation 7.2.3 Semi-natural grassland 7.2.4 Grip/drain blocking 7.2.5 Control of bracken, rushes and Molinia 7.2.6 Foddering sites 7.3 Disturbance 7.4 Fences and wires 7.5 Lek site clearance 7.6 Predation 7.6.1 Predator removal 7.6.2 Diversionary feeding 7.6.3 Habitat manipulation 7.7 Arable plots, supplementary feeding and grit 7.8 Shooting and other game 8. -

The Dark Side of Birds: Melanism—Facts and Fiction

Hein van Grouw 12 Bull. B.O.C. 2017 137(1) The dark side of birds: melanism—facts and fiction by Hein van Grouw Received 18 August 2016; revised 20 January 2017; published 13 March 2017 Summary.—Melanism is generally defined as an increase of dark pigment in the plumage, resulting in a blackish appearance. Furthermore, melanism is often associated with mutations of one gene that encodes the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), a protein involved in regulating melanin pigmentation. However, there is often no increase of pigment and melanism does not necessarily involve dark pigment alone. Also, many different mutations in many different genes promote melanism, which may explain why it is the commonest colour morph in birds. In the past, melanistic birds were sometimes mistakenly named as new species. Ironically, it now appears that melanistic birds do indeed differ from their normal- coloured conspecifics in more than just colour. ‘Every morphism thus has implications in the field of genetics, ecology, selection theory, field natural history, and taxonomy.’ (J. Huxley, 1955) Melanism, from the Greek melanos (= dark- coloured), is generally defined as an increased amount of dark pigmentation (melanin). However, in this paper it will be demonstrated that an aberrant dark plumage is not necessarily the result of increased amounts of pigment, and that melanism can result in a paler plumage than normal. Colour aberrations, especially melanism, have always confused ornithologists. In the past, when nothing was known concerning plumage pigmentation and mutations, aberrant-coloured birds were often viewed as being new taxa, and were even described scientifically. Perhaps the oldest and best-known example of a melanistic aberration named as a new species is Mountain Partridge Perdix montana (Brisson 1760). -

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: Sweden

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: Sweden Updated in November 2014 Updated in August 2016 HUNTING AND TRAPPING LEGISLATION/ RESOURCES Name of main legislation: Jaktlag (1987:259) and Jaktförordning (1987:905) Year of publication: 1987 Supporting legislation: Vapenlag (1996:67) - Weapon legislation Vapenförordning (1996:70) - Weapon legislation Lag (2000:592) om viltvårdsområden - Game areas legislation Viltskadeförordning (2001:724) - Game damage legislation Artskyddsförordning (2007:845) - Species protection legislation Djurskyddslag (1988:534) - Animal protection legislation Djurskyddsförordning (1988:539) - Animal protection legislation Legislation updates: Can be seen in the names of the legislations Hunting legislation (web link): http://www.notisum.se/rnp/sls/lag/19870259.HTM and http://www.notisum.se/rnp/sls/lag/19870905.HTM Authority in charge of controlling hunting (web link): Swedish Environmental Protection Agency http://www.naturvardsverket.se/ Major inconsistencies or loopholes detected (if yes please describe): Any bird nest is allowed to be removed including eggs and young if it is situated on/in your house or on/in your farm and causing a major damage or major inconvenience Derogations (on EU Birds Directive and/or Bern Convention): Pesticide hunting of Barnacle Goose is permitted and the species is listed both in EU Birds Directive annex 1 and Bern convention annex 2 Pesticide hunting of Eurasian Tree Sparrow is permitted and the species is not listed in EU Birds Directive annex 2 and not listed Bern convention annex 3 as species not included in the general protection of birds Pesticide hunting of House Sparrow is permitted and the species is not listed in EU Birds Directive annex 2, but is listed Bern convention annex 3 as species not included in the general protection of birds HUNTING AND TRAPPING: METHODS AND RESTRICTIONS Legal methods/restrictions Notes Hunting can be done with both shot guns Regulations are that Steel pellets are to be used Hunting and small calibre rifles. -

Conserving the Black Grouse

Conserving the black grouse A practical guide produced by the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust for farmers, landowners and local Biodiversity Action Plan groups www.gwct.org.uk A bird of the upland fringe Black grouse nutrition The staple foods of black grouse are heather and bilberry, but black grouse like buds, leaves, flowers, seeds, stems and even the spore capsules of Pictures by LauriePictures by Campbell mosses and twigs of several trees. Spring Black grouse favour cotton grass flower buds and larch buds. Other foods are herbs such as buttercup, sorrel and marigold found in unimproved Black grouse on a lek in the transition zone between forest and moorland. (Laurie Campbell) pastures and hay meadows. Black grouse are birds of edge habitats. They like, in particular, the transition zone between northern forest and moorland heath. In this habitat they can shelter in Summer the forest in the worst winter weather, feed on tree buds in spring and, in summer, In the summer, black grouse go for they can nest on open ground and forage with their chicks among the grasses and flowers, fruits heathland shrubs. and seeds, The black grouse has a spectacular communal breeding system. At dawn in rather than spring, males (blackcock) congregate on traditional display grounds (referred to leaves. They as a lek). Here they stake out small patches of ground on to which they entice like the seeds females for mating. of grasses, Females (greyhens) are cryptically coloured in mottle brown and lay their eggs rushes and in thick ground vegetation within a kilometre or so of the lek.