Sculpturecenter Tue Greenfort: Garbage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

1 Marais Des Cygnes River Basin Total Maximum Daily

MARAIS DES CYGNES RIVER BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Water Body: Spring Creek Park Lake Water Quality Impairment: Eutrophication bundled with Aquatic Plants 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Upper Marais des Cygnes County: Douglas HUC 8: 10290101 HUC 11 (HUC 14): 070 (020) Drainage Area: Approximately 1.43 square miles. Conservation Pool: Area = 8.5 acres, Mean Depth = 0.8 meter Designated Uses: Primary & Secondary Contact Recreation; Expected Aquatic Life Support; Food Procurement 1998 303d Listing: Table 4 - Water Quality Limited Lakes Impaired Use: All uses are impaired to a degree by eutrophication Water Quality Standard: Nutrients - Narrative: The introduction of plant nutrients into streams, lakes, or wetlands from artificial sources shall be controlled to prevent the accelerated succession or replacement of aquatic biota or the production of undesirable quantities or kinds of aquatic life. (KAR 28-16-28e(c)(2)(B)). The introduction of plant nutrients into surface waters designated for primary or secondary contact recreational use shall be controlled to prevent the development of objectionable concentrations of algae or algal by-products or nuisance growths of submersed, floating, or emergent aquatic vegetation. (KAR 28-16-28e(c)(7)(A)). 2. CURRENT WATER QUALITY CONDITION AND DESIRED ENDPOINT Level of Eutrophication: Hypereutrophic, Trophic State Index = 68.30 Monitoring Sites: Station 066801 in Spring Creek Park Lake (Figure 1) Period of Record Used: One survey in 1989. 1 Figure 1 Spring Creek Park Lake Baldwin City Drainage Area = 1.4 square miles 10290101070020 HUC 14 W Streams a City l n Drainage Area SPRING CREEK PARK LAKE u t Lakes C r N DG W E 0.8 0 0.8 1.6 Miles S Current Condition: The average chlorophyll a concentration was 46.8 ppb in 1989. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

In New York City

Outdoors Outdoors THE FREE NEWSPAPER OF OUTDOOR ADVENTURE JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2009 iinn NNewew YYorkork CCityity Includes CALENDAR OF URBAN PARK RANGER FREE PROGRAMS © 2009 Chinyera Johnson | Illustration 2 CITY OF NEW YORK PARKS & RECREATION www.nyc.gov/parks/rangers URBAN PARK RANGERS Message from: Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian To counteract this problem, the American Littoral Society in partnership with NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, National Park Service, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, NY State Department of Environmental Conservation, Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers, NYC Audubon Society, NYC Sierra Club and many other groups are working on various projects designed to remove debris and help restore the bay. This spring, we’ve organized a restoration cleanup and marsh planting at Plum Beach, a section of Gateway National Recreation Area and a major spawning beach for the ancient horseshoe crab. In May and June during the high tides, the crabs come ashore to lay their eggs as they’ve done for millions of years. This provides a critical food source for the many species of shorebirds that are migrating through New York City. Small fi sh such as mummichogs and killifi sh join in the feast as well. JAMAICA BAY RESTORATION PROJECTS: Since 1986, the Littoral Society has been organizing annual PROTECTING OUR MARINE LIFE shoreline cleanups to document debris and create a greater public awareness of the issue. This September, we’ll conduct Home to many species of fi sh & wildlife, Jamaica Bay has been many cleanups around the bay as part of the annual International degraded over the past 100 years through dredging and fi lling, Coastal Cleanup. -

City Council District 32

Rank by Largest Number Rank by Highest Percent City Council of Family Shelter Units of Homeless Students District 32 9 33 11 45 Eric Ulrich out of 15 districts out of 51 districts out of 15 districts out of 51 districts Rockaway Beach / Woodhaven in Queens in New York City in Queens in New York City Highlights Community Indicators Family Shelters Homelessness and Poverty Among Students CCD32 QN NYC Despite almost 2,000 District 32 students who 33 units n Homeless (N=750) 3% 4% 8% had been homeless, there is one family shelter in 2% of Queens units n Formerly Homeless (N=1,205) 5% 3% 4% 0.3% of NYC units the district with capacity for just 33 families. n Housed, Free Lunch (N=16,066) 69% 62% 60% 1 family shelter More than half of all remaining affordable units n Housed, No Free Lunch (N=5,252) 23% 30% 28% – of Queens shelters in District 32 are at risk of being lost in the 0.3% of NYC shelters Educational Outcomes of Homeless Students CCD32 QN NYC next five years. Chronic Absenteeism Rate 33% 31% 37% N eighborhood Dropout Rate 17% 16% 18% District 32 students of households 1 out of 12 Graduation Rate 57% 62% 52% 29% experienced homelessness in the last five years are severely rent burdened Math Proficiency 3–8 Grade 28% 26% 18% ELA Proficiency 3–8 Grade 28% 20% 14% 10% of people are unemployed Received IEP Late 56% 58% 62% Community Resources of people work Homebase: Homelessness Prevention 0 33% Affordable & Public Housing in low-wage occupations NYC and NYS Job Centers 0 Adult and Continuing Education n n n n 4 2,867 1,994 18% of people -

What Is the Natural Areas Initiative?

NaturalNatural AAreasreas InitiativeInitiative What are Natural Areas? With over 8 million people and 1.8 million cars in monarch butterflies. They reside in New York City’s residence, New York City is the ultimate urban environ- 12,000 acres of natural areas that include estuaries, ment. But the city is alive with life of all kinds, including forests, ponds, and other habitats. hundreds of species of flora and fauna, and not just in Despite human-made alterations, natural areas are spaces window boxes and pet stores. The city’s five boroughs pro- that retain some degree of wild nature, native ecosystems vide habitat to over 350 species of birds and 170 species and ecosystem processes.1 While providing habitat for native of fish, not to mention countless other plants and animals, plants and animals, natural areas afford a glimpse into the including seabeach amaranth, persimmons, horseshoe city’s past, some providing us with a window to what the crabs, red-tailed hawks, painted turtles, and land looked like before the built environment existed. What is the Natural Areas Initiative? The Natural Areas Initiative (NAI) works towards the (NY4P), the NAI promotes cooperation among non- protection and effective management of New York City’s profit groups, communities, and government agencies natural areas. A joint program of New York City to protect natural areas and raise public awareness about Audubon (NYC Audubon) and New Yorkers for Parks the values of these open spaces. Why are Natural Areas important? In the five boroughs, natural areas serve as important Additionally, according to the City Department of ecosystems, supporting a rich variety of plants and Health, NYC children are almost three times as likely to wildlife. -

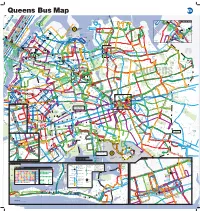

Queens Bus Map a Map of the Queens Bus Routes

Columbia University 125 St W 122 ST M 1 6 M E 125 ST Cathedral 4 1 Pkwy (110 St) 101 M B C M 5 6 3 116 St 102 125 St W 105 ST M M 116 St 60 4 2 3 Cathedral M SBS Pkwy (110 St) 2 B C M E 126 ST 103 St 1 MT MORRIS PK W 103 M 5 AV M E 124 2 3 102 10 E 120 ST M Central Park ST North (110 St) M MADISON AV 35 1 M M M B C 103 1 2 3 4 1 M 103 St 96 St 15 M 110 St 1 E 110 ST6 SBS QW 96 ST ueens Bus Map RANDALL'S BROADWAY 1 ISLAND B C 86 St NY Water 96 St Taxi Ferry W 88 ST Q44 SBS 44 6 to Bronx Zoo 103 St SBS M M MADISON AV Q50 15 35 50 WHITESTONE COLUMBUS AV E 106 ST F. KENNEDY COLLEGE POINT to Co-op City SBS 96 St 3 AV SHORE FRONT THROGS NECK BRIDGE B C BRIDGE CENTRAL PARK W 6 PARK 7 AV 2 AV BRIDGE POWELLS COVE BLVD 86 St 25 WHITESTONE CLI 147 ST N ROBERT ED KOCH LIC / Queens Plaza 96 St 5 AV AV 15A QUEENSBORO R 103 103 150 ST N 10 15 1 AV R W Q D COLLEGE POINT BLVD T 41 AV M 119 ST BRIDGE B C R 9 AV O 66 37 AV 15 FD NVILLE ST 81 St 96 ST QM QM QM QM M 7 AV 9 AV 69 38 AV 5 AV RIKERS POPPENHUSEN AV R D 102 1 2 3 4 21 St 35 NTE R 102 Queens- WARDS E 157 ST M 4 100 ISLAND 9 AV C 44 11 AV QM QM QM QM QM bridge 160 ST 166 ST 9 154 ST 162 ST 1 M M M ISLAND AV 15A 5 6 10 12 15 F M 5 6 SBS UTOPIA 39 AV 1 15 60 Q44 FORT QM QM QM QM QM 10 M 86 St COLLEGE BEECHHURST 13 Next stop QM 14 AV 15 PKWY TOTTEN 21 ST 102 M 111 ST 25 16 17 20 18 21 CRESCENT ST 2 86 St SBS POINT QM QM QM 14 AV 123 ST SERVICE RD NORTH QNS PLZ N 39 Av 2 14 AV Lafayette Av 2 QM QM QM QM QM QM M M Q 65 76 2 32 16 E 92 ST 21 AV 14 AV 20B 32 40 AV N W M 101 QM 2 24 31 32 34 35 3 LAGUARDIA 14 RD 15 AV E M E 91 ST 15 AV 32 SER 14 RD QM QM QM QM QM QM M 3 M ASTORIA WA 31 ST 101 21 ST 100 VICE RD S. -

Parks and Recreation VISION STATEMENT: We Enhance, Promote, and Maintain Outstanding Outdoor Trail, Park and Recreational Facilities

CHAPTER 7 PARKS AND RECREATION VISION STATEMENT: We enhance, promote, and maintain outstanding outdoor trail, park and recreational facilities. 127 RED WING 2040 COMMUNITY PLAN O verview Some History Levee Park was the first major project undertaken, In Red Wing we have a deep attachment to our city’s in 1904. In an agreement between the city and Parks, trails, and natural areas are defining Milwaukee Road, the railroad agreed to construct elements of a community’s quality of life. Our city’s past and a progressive attitude toward its future. This perspective is certainly true about our city’s a new depot and donated $20,550 to the city to unique natural setting heightens the importance begin improvement of the levee area. The classically of preserving natural resources, promoting park system. Much of what is now the backbone of the Red Wing park system was an outgrowth of the designed park was completed between 1905 recreation, and strengthening connections to and 1906. Around this time, John Rich Park, Red Red Wing’s scenic amenities. As discussed in the “City Beautiful” movement of the early 20th century. Spawned by the Chicago Columbian Exposition of Wing’s gateway park area, was also completed Green Infrastructure chapter, the 2040 Community at the entrance to downtown. John Rich was a Plan views parks and open spaces as essential 1893, City Beautiful affected architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning for the following founding member of the Red Wing Civic League components of the city’s green infrastructure. This and personally financed the development of network of greenspace provides immeasurable two decades. -

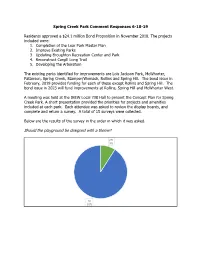

Spring Creek Park Comment Report

Spring Creek Park Comment Responses 6-18-19 Residents approved a $24.1 million Bond Proposition in November 2018. The projects included were: 1. Completion of the Lear Park Master Plan 2. Improve Existing Parks 3. Updating Broughton Recreation Center and Park 4. Reconstruct Cargill Long Trail 5. Developing the Arboretum The existing parks identified for improvements are Lois Jackson Park, McWhorter, Patterson, Spring Creek, Stamper/Womack, Rollins and Spring Hill. The bond issue in February, 2019 provides funding for each of these except Rollins and Spring Hill. The bond issue in 2023 will fund improvements at Rollins, Spring Hill and McWhorter West. A meeting was held at the IBEW Local 738 Hall to present the Concept Plan for Spring Creek Park. A short presentation provided the priorities for projects and amenities included at each park. Each attendee was asked to review the display boards, and complete and return a survey. A total of 15 surveys were collected. Below are the results of the survey in the order in which it was asked. Should the playground be designed with a theme? yes 9% no 91% Please list in order of preference the top 3 pieces of equipment. Motion Nets Climbers Stand alone slides Arch swings Nature Play Is the location of the shade correct? no 11% yes 89% How frequently is the basketball court used? Never Rarely 0% 7% Occasionally 29% Frequently 64% Park Maintenance 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 CLEANLINESS SAFETY FRIENDLINESS Anything missed/additional comments This open-ended question allowed respondents to provide us with suggestions on anything we missed in the concept or provide additional comments. -

Spring Creek Park, 1988

Natural Area Mapping and Inventory of Spring Creek 1988 Survey Prepared by the Natural Resources Group Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor Adrian Benepe, Commissioner Spring Creek Natural Area Mapping & Inventory Surveyed July 1988 166 acres Introduction City of New York Parks & Recreation (DPR) manages one of the most extensive and varied park systems of any city in the world. These 29,000 acres of city park property occupy about 15 percent of New York City’s total area. In addition to flagship parks such as Central Park and Prospect Park, the city’s parklands include over 11,000 acres of natural areas. Until the 1980’s, the Parks Department was primarily concerned with developed landscapes and recreation facilities rather than natural areas. In the absence of a comprehensive management policy, these areas succumbed to invasive species, pollution and erosion. In 1984, Parks established the Natural Resources Group (NRG) with a mandate to acquire, restore and manage natural areas in New York City. The wetlands, forests, meadows, and shorelines under NRG’s jurisdiction provide valuable habitat for hundreds of species, from rare wildflowers to endangered birds of prey. In addition to the goals mentioned above, NRG serves as a clearinghouse for technical research to aid in the protection and restoration of the city's natural resources. This inventory of Spring Creek was conducted in 1988 as part of NRG’s commitment to improving the natural areas of New York City parks. Spring Creek Park is located in Northern Jamaica Bay and contains the largest amount of undeveloped land and wetlands in the northern Jamaica Bay area. -

3Rd QTR PARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS (All Figures Are Subject to Further Analysis and Revision) Report Covering the Period Between July1, 2015 and Sept

3rd QTR PARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS (All figures are subject to further analysis and revision) Report covering the period Between July1, 2015 and Sept. 30, 2015 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY MURDER RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.747 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 0 0 0 0 1 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.430 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 002 1 0 3 0 6 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.564 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 1 0 5 0 7 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.320 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.690 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 025 6 1 9 0 23 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.970 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.000 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 003 0 0 0 0 3 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.430 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 1 0 1 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.373 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 101 2 0 2 0 6 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.350 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 0 0 0 0 1 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.514 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 2 0 2 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.250 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 005 3 0 7 0 15 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.860 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 003 2 1 0 0 6 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.160 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.800 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 1 0 0 0 2 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.203 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 004 2 0 8 0 14 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.000 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 1 0 1 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.983 ONE -

The Floridan Aquifer Within the Marianna Lowlands, 2003, Froede

SOUTHEASTERN GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY FIELD TRIP GUIDEBOOK 43 THE FLORIDAN AQUIFER WITHIN THE MARIANNA LOWLANDS Compiled And Edited By Carl R. Froede Jr. August 2, 2003 Southeastern Geological Society P.O. Box 1634 Tallahassee, Florida 32302 THE FLORIDAN AQUIFER WITHIN THE MARIANNA LOWLANDS SOUTHEASTERN GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Field Trip Guidebook 43 Summer Field Trip August 2, 2003 FIELD TRIP COMMITTEE: Carl R. Froede Jr., US EPA Region 4, Atlanta, GA Harley Means, Florida Geological Survey, Tallahassee, FL Dr. Jonathan R. Bryan, Okaloosa-Walton Community College, Niceville, FL Dr. Brian R. Rucker, Pensacola Junior College, Pensacola, FL 2003 SEGS OFFICERS President - Harley Means Vice President - Carl R. Froede Jr. Secretary/Treasurer - Sandra Colbert Membership - Bruce Rodgers (Past President) Guidebook Compiled And Edited By: Carl R. Froede Jr. 2003 Published by: THE SOUTHEASTERN GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY P.O. Box 1634 Tallahassee, FL 32302 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction/Acknowledgments 1 Field Trip Overview 2 (Carl R. Froede Jr.) Physiography of the Marianna Lowlands Province 3 (Carl R. Froede Jr.) Overview of the Geology of the Marianna Lowlands Province 7 (Carl R. Froede Jr.) Agricultural Impact to Merritt’s Mill Pond 14 (Harley Means) Historical Overview of the Florida Caverns, Jackson Blue Springs, and Merritt’s Mill Pond 18 (Dr. Brian R. Rucker) Florida Caverns Karst 22 (Gary L. Maddox, P.G.) Jackson Blue Springs 27 (Internet Information) Field Trip Stops and Map 28 (Carl R. Froede Jr.) iii iv Introduction/Acknowledgments The Marianna Lowlands physiographic province is the setting for the 43rd annual Southeastern Geological Society field trip. Key to this area are surface outcrops of the Floridan aquifer–composed of a number of limestone strata ranging in age from Eocene to Miocene.