Ethic Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Melbourne-Dreaming-Intro 1.Pdf (Pdf, 1.91

ABOUT THIS BOOK Melbourne Dreaming is both a guide book and social history of Melbourne, and the events and cultural traditions that have shaped local Aboriginal people’s lives. It aims to show where to look to gain a better understanding of the rich heritage and complex culture of Aboriginal people in Melbourne both before and since colonisation. It was first published in 1997. This is a completely updated and expanded edition. Melbourne Dreaming provides practical information on visiting both historical and contemporary sites located in the city centre, surrounding suburbs and outer areas. Arranged into seven precincts, Melbourne Dreaming takes you to beaches, parklands, camping places, historical sites, exhibitions, cultural displays and buildings. For Melbourne’s Aboriginal people the landscape prior to European settlement over which we travel was the face of the divine — the imprint of the ancestral creation beings that shaped the landscape on their epic journeys. Exploring Melbourne’s Aboriginal places is a way of paying respect to this sacred tradition while learning more about our shared and ancient history. Sites include locations and traces of important places before European settlement in 1835 such as shell middens, scarred trees, wells, fish traps, mounds and quarries. Other sites describe critical events that occurred because of the impact of European settlement. More recent places are the focus of contemporary life. What these places share in common is that each illustrates an important part of the overall story of the first inhabitants, the Kulin. Stories and photographs of some places of interest which have restricted access or cannot be visited have also been included. -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

Learning from Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener

Journal of Public Pedagogies, Number 2, 2017 Where the Wild Things are: Learning from Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, Brook Andrew and Trent Walter 1 Reviewed by Jayson Cooper 1 Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner is a commemorative marker by artists Brook Andrew and Trent Walter, commissioned by the City of Melbourne in early 2016, and opened publicly on 11 September 2016. Journal of Public Pedagogies, Number 2, 2017 Published by Public Pedagogies Institute: www.publicpedagogies.org Open Access article distributed under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 license URL http://jpp.vu.edu.au/ Journal of Public Pedagogies, No. 2, 2017 Jayson Cooper Places are pedagogical; and they teach through a range of ways. In recent public pedagogy discourse Biesta (2014) puts forth three forms of public pedagogy. These three forms of publicness are; pedagogy for the public; pedagogy of the public; and pedagogy in the in- terests of publicness. What Biesta offers with these views of pedagogy in the public sphere, is an understand of the ways we teach and learn in public places, and how that pedagogy is performed. In particular a pedagogy in the interest of publicness sees grassroots commu- nity led pedagogy that acts in the interest of publicness. This provides a lens to examine how pedagogy and knowledge is held in public spaces. When thinking about the public, Savage (2014) contributes by directing our thinking about how teaching and learning lives in the public sphere. Savage’s idea of the concrete public views the public space as being a spatially bound site, ‘such as urban streetscapes or housing estates’ (p. -

NORTH CENTRAL WATERWAY STRATEGY 2014-2022 CONTENTS Iii

2014-2022 NORTH CENTRAL WATERWAY STRATEGY Acknowledgement of Country The North Central Catchment Management Authority acknowledges Aboriginal Traditional Owners within the region, their rich culture and spiritual connection to Country. We also recognise and acknowledge the contribution and interest of Aboriginal people and organisations in land and natural resource management. Document name: 2014-22 North Central Waterway Strategy North Central Catchment Management Authority PO Box 18 Huntly Vic 3551 T: 03 5440 1800 F: 03 5448 7148 E: [email protected] www.nccma.vic.gov.au © North Central Catchment Management Authority, 2014 A copy of this strategy is also available online at: www.nccma.vic.gov.au The North Central Catchment Management Authority wishes to acknowledge the Victorian Government for providing funding for this publication through the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy. This publication may be of assistance to you, but the North Central Catchment Management Authority (North Central CMA) and its employees do not guarantee it is without flaw of any kind, or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on information in this publication. The North Central Waterway Strategy was guided by a Steering Committee consisting of: • James Williams (Steering Committee Chair and North Central CMA Board Member) • Richard Carter (Natural Resource Management Committee Member) • Andrea Keleher (Department of Environment and Primary Industries) • Greg Smith (Goulburn-Murray Water) • Rohan Hogan (North Central CMA) • Tess Grieves (North Central CMA). The North Central CMA would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Steering Committee, Natural Resource Management Committee (NRMC) and the North Central CMA Board. -

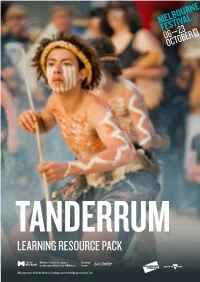

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835 By Glen Foster An historical game using role-play and cards for 4 players from upper Primary school to adults. © Glen Foster, 2019 1 Published by Port Fairy Historical Society 30 Gipps Street, Port Fairy. 3284. Telephone: (03) 5568 2263 Email: [email protected] Postal address: Port Fairy Historical Society P.O. Box 152, Port Fairy, Victoria, 3284 Australia Copyright © Glen Foster, 2019 Reproduction and communication for educational and private purposes Educational institutions downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own educational purposes. The general public downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own private use. Requests and enquiries for further authorisation should be addressed to Glen Foster: email: [email protected]. Disclaimers These materials are intended for education and training and private use only. The author and Port Fairy Historical Society accept no responsibility or liability for any incomplete or inaccurate information presented within these materials within the poetic license used by the author. Neither the author nor Port Fairy Historical Society accept liability or responsibility for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered as a result of direct or indirect use or application of this material. Print on front page shows members of the Kulin Nations negotiating a “treaty” with John Batman in 1835. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia. George Rossi Ashton, artist. © Glen Foster, 2019 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

The Health of Streams in the Wimmera Basin

ENVIRONMENT REPORT THE HEALTH OF STREAMS IN THE WIMMERA BASIN A REPORT BY EPA VICTORIA AND WIMMERA CMA Publication 1233 June 2008 1 THE HEALTH OF STREAMS IN THE WIMMERA BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Broadscale snapshot of condition ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 The basin............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Description of the catchments ...................................................................................................................... 4 Rainfall and stream flows .............................................................................................................................. 4 Assessment methods ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Rapid bioassessment (RBA)........................................................................................................................... 5 Data sources................................................................................................................................................. -

Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania Ningina Tunapri Education

voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry education guide Written by Andy Baird © Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 2008 voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry A guide for students and teachers visiting curricula guide ningenneh tunapry, the Tasmanian Aboriginal A separate document outlining the curricula links for exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and the ningenneh tunapry exhibition and this guide is Art Gallery available online at www.tmag.tas.gov.au/education/ Suitable for middle and secondary school resources Years 5 to 10, (students aged 10–17) suggested focus areas across the The guide is ideal for teachers and students of History and Society, Science, English and the Arts, curricula: and encompasses many areas of the National Primary Statements of Learning for Civics and Citizenship, as well as the Tasmanian Curriculum. Oral Stories: past and present (Creation stories, contemporary poetry, music) Traditional Life Continuing Culture: necklace making, basket weaving, mutton-birding Secondary Historical perspectives Repatriation of Aboriginal remains Recognition: Stolen Generation stories: the apology, land rights Art: contemporary and traditional Indigenous land management Activities in this guide that can be done at school or as research are indicated as *classroom Activites based within the TMAG are indicated as *museum Above: Brendon ‘Buck’ Brown on the bark canoe 1 voices of aboriginal tasmania contents This guide, and the new ningenneh tunapry exhibition in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, looks at the following -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930: Bibliography

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930: Bibliography Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930: Bibliography © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Brown, Mark; Smith, Robyn; Richards, Jonathan; Anders, Robert J;. Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack, 2018. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930 1 Sources 2 Abbreviations 2 UNPUBLISHED SOURCES 2 STATE RECORDS OF NSW (SRNSW) 3 MITCHELL LIBRARY – STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES, SYDNEY (ML) 3 COURT REPORTS 3 PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON (PRO) 3 OXLEY MEMORIAL LIBRARY STATE LIBRARY OF QUEENSLAND 3 QUEENSLAND STATE ARCHIVES (QSA) 4 TASMANIAN ARCHIVE AND HERITAGE OFFICE, TASMANIA (TAHO) 4 VICTORIAN PUBLIC RECORDS SERIES (VPRS), Melbourne 4 STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA - LA TROBE LIBRARY, Melbourne 4 MANUSCRIPTS 5 THESES AND TYPESCRIPTS 5 NEWSPAPERS 5 PRINTED SOURCES 7 1 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930: Bibliography Sources Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania BC Brisbane Courier BCHAR Barrow Creek Heritage Assessment Report, (NT) BPP British Parliamentary Papers CCCL Chief Commissioner of Crown Lands CSIL Colonial Secretary In Letters CSO Colonial Secretary’s Office -

Central Region

Section 3 Central Region 49 3.1 Central Region overview .................................................................................................... 51 3.2 Yarra system ....................................................................................................................... 53 3.3 Tarago system .................................................................................................................... 58 3.4 Maribyrnong system .......................................................................................................... 62 3.5 Werribee system ................................................................................................................. 66 3.6 Moorabool system .............................................................................................................. 72 3.7 Barwon system ................................................................................................................... 77 3.7.1 Upper Barwon River ............................................................................................... 77 3.7.2 Lower Barwon wetlands ........................................................................................ 77 50 3.1 Central Region overview 3.1 Central Region overview There are six systems that can receive environmental water in the Central Region: the Yarra and Tarago systems in the east and the Werribee, Maribyrnong, Moorabool and Barwon systems in the west. The landscape Community considerations The Yarra River flows west from the Yarra Ranges