PROCESSING the PAPERS of STATE LEGISLATOR MICHAEL MACHADO a Project Prese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sound Evidence: an Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media

Sound Evidence: An Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media by Dimitrios Pavlounis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Screen Arts and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy, Chair Emeritus Professor Richard Abel Professor Lisa Ann Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar Professor Gerald Patrick Scannell © Dimitrios Pavlounis 2016 For My Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My introduction to media studies took place over ten years ago at McGill University where Ned Schantz, Derek Nystrom, and Alanna Thain taught me to see the world differently. Their passionate teaching drew me to the discipline, and their continued generosity and support made me want to pursue graduate studies. I am also grateful to Kavi Abraham, Asif Yusuf, Chris Martin, Mike Shortt, Karishma Lall, Amanda Tripp, Islay Campbell, and Lees Nickerson for all of the good times we had then and have had since. Thanks also to my cousins Tasi and Joe for keeping me fed and laughing in Montreal. At the University of Toronto, my entire M.A. cohort created a sense of community that I have tried to bring with me to Michigan. Learning to be a graduate student shouldn’t have been so much fun. I am especially thankful to Rob King, Nic Sammond, and Corinn Columpar for being exemplary scholars and teachers. Never have I learned so much in a year. To give everyone at the University of Michigan who contributed in a meaningful way to the production of this dissertation proper acknowledgment would mean to write another dissertation-length document. -

Format Guide to Sound Recordings

National Archives & Records Administration October 2014 Format Guide to Sound Recordings: This document originated as project-specific guidance for the inventory, identification and basic description of a collection of disc recordings and open reel sound recordings dated from the late 1920’s through the early 1960’s from the holdings of the Office of Presidential Libraries. It contains references to individuals that have been concealed and to specific database elements that were used in the inventory project. ¼” Open Reel Magnetic tape was first introduced as a recording medium in 1928 in Germany, but innovations related to a alternating current biasing circuit revolutionized the sound quality that tape offered in the 1940 under the Nazis. After the war, with Axis controlled patents voided by the victorious Allies, magnetic tape technology rapidly supplanted sound recording to disc in radio production and music recording. Physically, the tape is a ribbon of paper or plastic, coated with ferric oxide (essentially a highly refined form of rust) wound onto a plastic spool housed in a small cardboard box. The most common width of magnetic tape used for audio was ¼” and it was supplied in reels of 3”, 5”, 7” and 10.5” diameters, with 7” being the most common. Original ¼” audio tape begins appearing in Presidential Library collections in the early 1950’s. The format was commonly used by the National Archives to create preservation and reference copies into the 1990’s. This use as a reproduction format may be its most common occurrence in the materials we are inventorying. Figure 1: A seven inch reel of 1/4" open reel audio tape Page 1 of 15 National Archives & Records Administration October 2014 Figure 2: Tape box containing a 7" reel of 1/4" open reel magnetic tape. -

1 Introdução E Apresentação

1 1 INTRODUÇÃO E APRESENTAÇÃO A proposta do presente estudo se justifica na busca da compreensão dos processos que envolvem a fruição em música. Para tanto desenvolvemos uma análise da relação do homem com a música, considerando a ampla teia de pressupostos ligados a contextos históricos, filosóficos e sociais. Norteados pelas teorias da estética da recepção, suas inferências e projeções no campo musical, este estudo visa investigar o processo produtivo em música sob a ótica do receptor. Trata-se, sobretudo, de uma análise da relação do receptor com os espaços formais de realização da música – no sentido tanto concreto quanto metafórico – nas contingências e circunstâncias que o cercam e conformam o ato da fruição. Discutiremos, portanto, ao longo da história da música ocidental, os lugares de produção e recepção da música, os conceitos de sentido, lingüisticidade musical e seus modos de apreensão, bem como os processos de estruturação musical numa perspectiva e estética vinculadas à acústica e à paisagem sonora. Norteados pelo Pensamento Complexo proposto por Edgar Morin, analisaremos a complexidade existente na trama do processo criativo sob a perspectiva do receptor; e, como se faz pertinente e imprescindível no raciocínio sistêmico, daremos igual atenção à obra e às intenções do autor. Em um primeiro momento, nosso foco será a obra, aqui tratada enquanto representação simbólica inserida no contexto em que foi criada. Sem a preocupação com a linearidade e a cronologia, primaremos por nos aproximar do que seria a gênese da obra, entendendo a mesma como um microcosmo artístico (fruto de uma organização de ordem cultural e cognitiva) e de um macrocosmo social (uma organização de ordem política e sócio- econômica). -

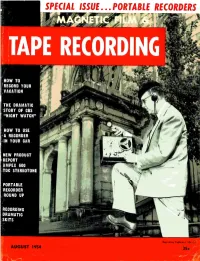

Tape Recording

SPECIAL ISSUE ... PORTABLE RECORDERS d- HOW TO RECORD YOUR VACATION THE DRAMATIC STORY OF CBS "NIGHT WATCH" HOW TO USE - A RECORDER IN YOUR CAR NEW PRODUCT REPORT AMPEX 600 TDC STEREOTONE PORTABLE RECORDER ROUND UP RECORDING DRAMATIC SKITS AUGUST 1954 polyester film offers you these important new advantages many times stronger withstands extreme temperatures impervious to moisture maximum storage life most permanent magnetic recording medium ever developed Audiotape on "Mylar" polyester film provides a degree of permanence and durability unattainable with any other base material. Its exceptional mechanical strength makes it practically unbreakable in normal use. Polyester remains stable over a temperature range from 58° below zero to 302° Fahren- heit. It is virtually immune to humidity or moisture in any concentration - can be stored for long periods of time without embrittling of the base material. The new polyester Audiotape has exactly the same mag- PHYSICAL PROPERTIES netic characteristics as the standard plastic -base Audiotape "Mylar" polyester film compared to ordinary plastic base material - assures the same BALANCED PERFORMANCE and (cellulose acetate) faithful reproduction that have made it first choice with so many professional recordists all over the world. 1 2 Mil 1.5 Mil Mil 1.5 Mil with breakage, high PROPERTY "MYLAR" "MYLAR" "MYLAR" Acetate If you have been troubled tape humidity or dryness, Audiotape on "Mylar" will prove well Tensile Strength, psi 25,000 25,000 25,000 11,000 worth the somewhat higher price. In standard thickness Impact Strength, kg -cm 90 170 200 10 (1' /z mil), for example, the cost is only 50% more than Tear Strength, grams 22 35 75 5 regular plastic base tape. -

Indiana University Bloomington Media Preservation Survey a Report by Mike Casey

Indiana University Bloomington Media Preservation Survey A Report By Mike Casey Data Collection, Interpretation, and Analysis: Patrick Feaster Survey Planning and Design, Data Analysis: Mike Casey Survey Supervision and Editorial Contributions: Alan Burdette SURVEY TASK FORCE Julie Bobay, Associate Dean for Collection Development and Digital Publishing, Wells Library Alan Burdette, Director, Archives of Traditional Music and Director, EVIA Digital Archive Mike Casey, Associate Director for Recording Services, Archives of Traditional Music Stacy Kowalczyk, Associate Director for Projects and Services, Digital Library Program, Wells Library Brenda Nelson‐Strauss, Head of Collections/Technical Services, Archives of African American Music and Culture Barbara Truesdell, Assistant Director, Center for the Study of History and Memory CONSULTANTS David Francis, Former Chief, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress Dietrich Schüller, Director Emeritus, Vienna Phonogrammarchiv Chris Lacinak, President, AudioVisual Preservation Solutions (technical consultant) SPECIAL THANKS Project Guidance: Ruth Stone, Associate Vice Provost, Office of the Vice Provost for Research Mark Hood, Susan Hooyenga, Martha Harsanyi, Julie Bobay, Mary Huelsbeck, Rachael Stoeltje, Phil Ponella, Phil Sutton, J. Kevin Wright, and the staff of the participating survey units PHOTO CREDITS Patrick Feaster, Alan Burdette, and Mike Lee Table of Contents Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….i List of Tables .....................................................................................................................iv -

Strategies and Solutions

Meeting the Challenge of Media Preservation: Strategies and Solutions Meeting the Challenge of Media Preservation: Strategies and Solutions Indiana University Bloomington Media Preservation Initiative Task Force Public Version September 2011 Our history is at risk Indiana University Bloom- ington is home to at least 3 million sound and moving image recordings, photos, documents, and artifacts. Well over half a million of these special holdings are part of audio, video, and film collections, and a large num- ber of them are one of a kind. These invaluable cultural and historical gems, and many more, may soon be lost. Forever. IMAGES, PREVIOUS PAGE: g The Archives of African g Gloria Gibson, Frances Stubbs, and founding director Phyllis American Music and Culture Klotman pose in 1985 with part of the Black Film Center/Archive’s has ninety-one audiocas- rich collection of films and related materials by and about African settes of interviews conducted Americans. Photo courtesy of the Black Film Center/Archive. by Michael Lydon with Ray Charles and his associates as background for the book Ray Charles: Man and Music. Image from IU News Room. g The Blackbird (1926), star- g Herman B Wells was an edu- g In 1947 Bill Garrett broke a ring Lon Chaney, is one of cational visionary who helped color barrier in major college many historically important transform Indiana University basketball by becoming the films found in the David S. into an internationally recog- first black player signed in Bradley Collection. Photo nized center of research and the Big Ten. He led the team courtesy of Lilly Library. -

Three (3) National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Records Management Documents, 2004-2017

Description of document: Three (3) National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Records Management Documents, 2004-2017 Requested date: 03-February-2017 Release date: 23-February-2017 Posted date: 20-May-2019 Records included: NARA Policy Directive 816 (NARA 816) Digitizing Activities for Enhanced Access, 2004 NARA Policy Directive 1571 (NARA 1571) Archival Storage Standards, 2002 (starts PDF page 15) NARA Lifecycle Data Requirements Guide, 2017 (starts PDF page 30) Source of document: FOIA Request FOIA Officer National Archives and Records Administration 8601 Adelphi Road, Room 3110 College Park, MD 20740 By Fax: (301) 837-0293 By E-mail: [email protected] Online:FOIAonline or www.foia.gov The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

The Better Sound of the Phonograph: How Come? How-To!*

UPDATES & extras: The Better Sound of the Phonograph: How come? How-to!* ***** 5-star review – A lot of the information ***** 5-star review – This book is essential reading comes from the author's extensive life-long for anyone who wants to get the best from their vinyl - professional experience in audio as well as his own and older shellac - records. How to get better sound by research and study. I learned more about the careful setting up your system. Constructional chapters importance of stylus shape, for example, in getting the show you how to make your own equipment with minimal most out of the record grooves without distortion. The skills and basic tools. I like this book because it is well author's no-nonsense approach is refreshing in this written, easy to understand and has very useful age of fantasy thinking by hi-fi hucksters selling snake illustrations. There's also access to online updates. What oil products to innocent audiophiles. His practicality makes this book so good is that it shows how great vinyl and focus on what is really important is a valuable playback does not need thousands of dollars (or your perspective. I'm glad he shared his insights, wisdom own currency) to achieve. – Richard Z, UK and information with all of us in this nice book. – Dirk ***** 5-star review – I intend to build both Wright, USA projects in the book preamp and tonearm. All in all a ***** 5-star review – Perfect for a techno-curious very thoughtful book on the turntable and it’s music-lover, it's a profusely illustrated and readable background science; would recommend it to anyone guide, with high-end knowledge that’s harder to find with the faintest interest.