Perspectives on Terrorism, Volume 8, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masterarbeit Abgabe PDF.Indd

ANNIKA THEOBALD – 311228 DIJONSTRASSE 2, 75173 PFORZHEIM Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst DESIGN & KYBERNETIK – Von der Dekodierung zur Synchronisation der Systeme FÜR JAMES CARSE1 ABSTRACT 1. Rajat Panwar, Robert Kozak and Ziel der vorliegenden Arbeit ist die Entwicklung eines Handlungs- Eric Hansen, For- ests, Business and modells zur Adressierung und Lösung komplexer gesellschaftlicher Sustainability, Fragestellungen – Der sogenannten bösartigen Probleme. 2015, S.11 Da es sich um eine wissenschaftliche Arbeit aus dem Kernbereich der Designdisziplin handelt, gibt das erste Kapitel einen Einblick in die Defi nition des der Arbeit zugrunde liegenden Designbegriffs, um so eine disziplinäre Verortung der Argumentation gewährleisten zu können. Es folgt eine Einführung in den Charakter bösartiger Probleme und die Erläuterung der Kernproblematik im Umgang mit selbigen. Anschließend werden die Kompetenzen der DesignerInnen beleuchtet, dabei vor allem die für die Adressierung relevanten. Da bösartige Probleme in ihrer Komplexität Teilbereiche ver- schiedener Disziplinen ansprechen und die Qualitäten der DesignerInnen allein nicht alle Anforderungen der Adressierung bedienen können, ergibt sich die Notwendigkeit einer Kooperation mit den Systemwissenschaften. Entsprechend der Darstellung der Qualitäten der Designer- Innen, werden daher auch die für die Adressierung entscheidenden Kompetenzen der Systemwissenschaften vorgestellt. Auf jene Qualifi kationen aufbauend, schließt sich eine schrittweise Beschreibung der im Rahmen der Arbeit erarbeiteten -

PENTTBOM CASE SUMMARY As of 1/11/2002

Law Enforcement Sensitive PENTTBOM CASE SUMMARY as of 1/11/2002 (LES) The following is a "Law Enforcement Sensitive" version of materials relevant to the Penttbom investigation. It includes an Executive Summary; a Summary of Known Associates; a Financial Summary; Flight Team Biographies and Timelines. Recipients are encouraged to forward pertinent information to the Penttbom Investigative Team at FBI Headquarters (Room 1B999) (202-324-9041), or the New York Office, (212-384-1000). Law Enforcement Sensitive 1 JICI 04/19/02 FBI02SG4 Law Enforcement Sensitive EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (LES) Captioned matter is a culmination of over a decade of rhetoric, planning, coordination and terrorist action by USAMA BIN LADEN (UBL) and the AL-QAEDA organization against the United States and its allies. UBL and AL-QAEDA consider themselves involved in a "Holy War" against the United States. The Bureau, with its domestic and international counterterrorism partners, has conducted international terrorism investigations targeting UBL, AL-QAEDA and associated terrorist groups and individuals for several years. (LES) In August 1996, USAMA BIN LADEN issued the first of a series of fatwas that declared jihad on the United States. Each successive fatwa escalated, in tone and scale, the holy war to be made against the United States. The last fatwa, issued in February 1998, demanded that Muslims all over the world kill Americans, military or civilian, wherever they could be found. Three months later, in May 1998, he reiterated this edict at a press conference. The United States Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, were bombed on August 7, 1998, a little more than two months after that May 1998 press conference. -

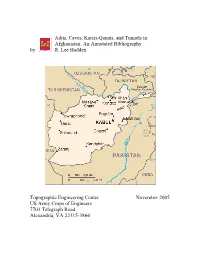

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: an Annotated Bibliography by R

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography by R. Lee Hadden Topographic Engineering Center November 2005 US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Alexandria, VA 22315-3864 Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels In Afghanistan Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE 30-11- 2. REPORT TYPE Bibliography 3. DATES COVERED 1830-2005 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER “Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats and Tunnels 5b. GRANT NUMBER In Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography” 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER HADDEN, Robert Lee 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Topographic Alexandria, VA 22315- Engineering Center 3864 9.ATTN SPONSORING CEERD / MONITORINGTO I AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Al Qaeda's Struggling Campaign in Syria: Past, Present, and Future

COVER PHOTO FADI AL-HALABI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES APRIL 2018 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Al Qaeda’s Struggling Washington, DC 20036 202 887 0200 | www.csis.org Campaign in Syria Past, Present, and Future AUTHORS Seth G. Jones Charles Vallee Maxwell B. Markusen A Report of the CSIS TRANSNATIONAL THREATS PROJECT Blank APRIL 2018 Al Qaeda’s Struggling Campaign in Syria Past, Present, and Future AUTHORS Seth G. Jones Charles Vallee Maxwell B. Markusen A Report of the CSIS TRANSNATIONAL THREATS PROJECT About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Thomas J. Pritzker was named chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in November 2015. Former U.S. deputy secretary of defense John J. -

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi'a and Sufi

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi’a and Sufi Shaykhs in Mid-Nineteenth- Century China Wang Jianping, Shanghai Normal University Abstract This article traces the activities of Ma Dexin, a preeminent Hui Muslim scholar and grand imam (akhund) who played a leading role in the Muslim uprising in Yunnan (1856–1873). Ma harshly criticized Shi’ism and its followers, the shaykhs, in the Sufi orders in China. The intolerance of orthodox Sunnis toward Shi’ism can be explained in part by the marginalization of Hui Muslims in China and their attempts to unite and defend themselves in a society dominated by Han Chinese. An analysis of the Sunni opposition to Shi’ism that was led by Akhund Ma Dexin and the Shi’a sect’s influence among the Sufis in China help us understand the ways in which global debates in Islam were articulated on Chinese soil. Keywords: Ma Dexin, Shi’a, shaykh, Chinese Islam, Hui Muslims Most of the more than twenty-three million Muslims in China are Sunnis who follow Hanafi jurisprudence when applying Islamic law (shariʿa). Presently, only a very small percentage (less than 1 percent) of Chinese Muslims are Shi’a.1 The historian Raphael Israeli explicitly analyzes the profound impact of Persian Shi’ism on the Sufi orders in China based on the historical development and doctrinal teachings of Chinese Muslims (2002, 147–167). The question of Shi’a influence explored in this article concerns why Ma Dexin, a preeminent Chinese Muslim scholar, a great imam, and one of the key leaders of the Muslim uprising in the nineteenth century, so harshly criticized Shi’ism and its accomplices, the shaykhs, in certain Sufi orders in China, even though Shi’a Islam was nearly invisible at that time. -

Staff Statement No

Outline of the 9/11 Plot Staff Statement No. 16 Members of the Commission, your staff is prepared to report its preliminary findings regarding the conspiracy that produced the September 11 terrorist attacks against the United States. We remain ready to revise our understanding of this subject as our work continues. Dietrich Snell, Rajesh De, Hyon Kim, Michael Jacobson, John Tamm, Marco Cordero, John Roth, Douglas Greenburg, and Serena Wille did most of the investigative work reflected in this statement. We are fortunate to have had access to the fruits of a massive investigative effort by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement agencies, as well intelligence collection and analysis from the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the State Department, and the Department of Defense. Much of the account in this statement reflects assertions reportedly made by various 9/11 conspirators and captured al Qaeda members while under interrogation. We have sought to corroborate this material as much as possible. Some of this material has been inconsistent. We have had to make judgment calls based on the weight and credibility of the evidence. Our information on statements attributed to such individuals comes from written reporting; we have not had direct access to any of them. Plot Overview Origins of the 9/11 Attacks The idea for the September 11 attacks appears to have originated with a veteran jihadist named Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM). A Kuwaiti from the Baluchistan region of Pakistan, KSM grew up in a religious family and claims to have joined the Muslim Brotherhood at the age of 16. -

CHEMICAL and BIOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS of JIHADI TERRORISM Animesh Roul

P a g e | 0 SSPC RESEARCH PAPER February 2016 APOCALYPTIC TERROR: CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS OF JIHADI TERRORISM Animesh Roul The threat of chemical and biological terrorism emanating from non-state actors, including the Islamic Jihadi organisations, which control large swathes of territories and resources, remains a major concern for nation states today. Over the years, the capability and intentions of Islamic jihadist groups have changed. They evidently prefer for more destructive and spectacular methods. This can be very well argued that if these weapons systems, materials or technologies were made available to them, they probably would use it against their enemy to maximize the impact and fear factor. Even though no terrorist group, including the Al Qaeda, so far has achieved success in employing these destructive and disruptive weapons systems or materials, in reality, various terrorist groups have been seeking to acquire WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction/Disruption) materials and its know-how. Apocalyptic Terror: Chemical and Biological Dimensions of Jihadi Terrorism The threat of chemical and biological terrorism emanating from non-state actors, including the Islamic Jihadi organisations, which control large swathes of territories and resources, remains a major concern for nation states today. Historically, no organised terrorist groups have perpetrated violent attacks using biological or chemical agents so far. Over the years, the capability and intentions of Islamic jihadist groups have changed. They are evidently preferring for more destructive and spectacular methods. This can be very well argued that if these weapons systems, materials or technologies were made available to them, they probably would use it against their enemy to maximize the impact and fear factor. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

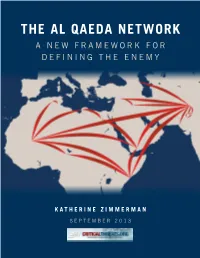

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product. -

From Cybernetics to Construction Cybernetics“

Fachhochschule Kärnten Carinthia University of Applied Sciences Villacher Straße 1 9800 Spittal an der Drau Tel : 0043(0)5/90500-0, Fax: -1110 [email protected] www.fh-kaernten.at DEGREE PROGRAM „CIVIL ENGINEERING“ MM AA SS TT EE RR TT HH EE SS II SS „From Cybernetics to construction cybernetics“ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the academic degree Dipl.-Ing. for „Civil engineering – Project Management“ Author: Lukas Gehwolf, BSc Registration number: 0810292014 Supervisor: Dipl.-Ing. Dr. techn. Otto Greiner Second supervisor: Dipl.-Ing. Dr. techn. Hans Steiner, MBA h.c. Spittal/Drau, September 2010 stamp of study program Statutory declaration Name: Lukas Gehwolf Registration number: 0810292014 Date of birth: 03.10.1981 Address: Markt 10 A-5611 Grossarl Statutory declaration I declare that I have authored this thesis independently, that I have not used other than the declared sources / resources, and that I have explicitly marked all material which has been quoted either literally or by content from the used sources. (place, date) (student´s signature) Introduction Introduction I would first like to thank all of those who contributed to the successful completion of this work. The completion of this paper would not have been possible without the help and support of countless individuals. I would especially like to mention my supervisors at the Carinthia University of Applied Sciences, Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Otto GREINER (Professor of Construction Project Management), Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Hans STEINER MBA h.c. (Landesinnungsmeister Stv. construction industry, Carinthia) and Prof. PhD. Stuart A. UMPLEBY (Department of Management) at George Washington University, they supported me with their great dedication and many valuable insights. -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

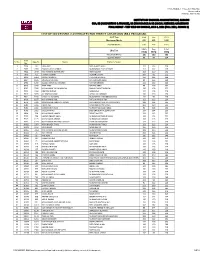

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Radical Islamist Groups in Germany: a Lesson in Prosecuting Terror in Court by Matthew Levitt

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 834 Radical Islamist Groups in Germany: A Lesson in Prosecuting Terror in Court by Matthew Levitt Feb 19, 2004 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Matthew Levitt Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis n February 5, 2004, a German court acquitted Abdelghani Mzoudi, a thirty-one-year-old native Moroccan, of O 3,066 counts of accessory to murder and membership in a terrorist organization (al-Qaeda). Mzoudi is suspected of having provided material and financial support to the Hamburg cell that helped organize and perpetrate the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. According to the presiding judge, Mzoudi was acquitted for lack of evidence, not out of a belief in the defendant's innocence. The acquittal was the most recent example of a growing dilemma faced by the United States and other countries in their efforts to prosecute suspected terrorists: how to gain access to intelligence for criminal proceedings without compromising the sources of that information. Indeed, Mzoudi's acquittal comes at a time when, despite nearly three years of fighting the war on terror, German intelligence claims that the presence of militant Islamist groups on German soil has reached new heights. U.S. officials face similar circumstances. Al-Qaeda in Germany Within days of the September 11 attacks, al-Qaeda activities in Germany quickly emerged as a key focus of the investigation. Three of the four suicide pilots -- Mohammed Atta, Marwan al-Shehi, and Ziad Jarrah -- were members of the Hamburg cell.