Cloud and Clothe. Hildegard of Bingen's Metaphors of the Fall Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Garment of Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Tradition

24 The Garmentof Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and ChristianTradition Stephen D. Ricks Although rarely occurring in any detail, the motif of Adam's garment appears with surprising frequency in ancient Jewish and Christian literature. (I am using the term "Adam's garment" as a cover term to include any garment bestowed by a divine being to one of the patri archs that is preserved and passed on, in many instances, from one generation to another. I will thus also consider garments divinely granted to other patriarchal figures, including Noah, Abraham, and Joseph.) Although attested less often than in the Jewish and Christian sources, the motif also occurs in the literature of early Islam, espe cially in the Isra'iliyyiit literature in the Muslim authors al ThaclabI and al-Kisa'I as well as in the Rasii'il Ikhwiin al ~afa (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Particularly when discussing the garment of Adam in the Jewish tradition, I will shatter chronological boundaries, ranging from the biblical, pseudepigraphic, and midrashic references to the garment of Adam to its medieval attestations. 1 In what fol lows, I wish to consider (1) the garment of Adam as a pri mordial creation; (2) the garment as a locus of power, a symbol of authority, and a high priestly garb; and (3) the garment of Adam and heavenly robes. 2 705 706 STEPHEN D. RICKS 1. The Garment of Adam as a Primordial Creation The traditions of Adam's garment in the Hebrew Bible begin quite sparely, with a single verse in Genesis 3:21, where we are informed that "God made garments of skins for Adam and for his wife and clothed them." Probably the oldest rabbinic traditions include the view that God gave garments to Adam and Eve before the Fall but that these were not garments of skin (Hebrew 'or) but instead gar ments of light (Hebrew 'or). -

Eve: Influential Glimpses from Her Story

Scriptura 90 (2005), pp. 765-778 EVE: INFLUENTIAL GLIMPSES FROM HER STORY Maretha M Jacobs University of South Africa Abstract Having inherited Christianity and its institutional manifestations from their male ancestors, whose voices were for many centuries, and are still, inextricably linked to that of God, women only recently started to ask the all important why-questions about the Christian religion, its origin and its effects on their lives. In this article a look is taken at some glimpses from the mostly male story about Eve, by which women’s lives were deeply influenced. By detecting the contexts, history, moti- vations and interests behind aspects of this story, it is exposed for what it is: A male construct or constructs and not “how it really was and is” about Eve and her female descendants. Keywords: Eve, History of Interpretation, Feminist Criticism Introduction Take a narrative of human origins which originated in a patriarchal culture in which a woman plays a prominent role, though she is – supposedly – also the biggest culprit, include this narrative, and character, in the genre Holy Scriptures, situate it at a strategic position within these Scriptures where it becomes not merely a, but the story of human origins, and later on especially that of sin, leave – for many centuries – its interpretation mainly to the “other” sex within ever changing contexts, though predominantly those unfriendly to women, make it an essential building block of a belief system. And you are left with the kind of interpretation history and impact of the story of Eve, which has for a long time been the dominant one. -

The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 3.1, 3–27 © 2000 [2010] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press THE FALL OF SATAN IN THE THOUGHT OF ST. EPHREM AND JOHN MILTON GARY A. ANDERSON HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL CAMBRIDGE, MA USA ABSTRACT In the Life of Adam and Eve, Satan “the first-born” refused to venerate Adam, the “latter-born.” Later writers had difficulty with the tale because it granted Adam honors that were proper to Christ (Philippians 2:10, “at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend.”) The tale of Satan’s fall was then altered to reflect this Christological sensibility. Milton created a story of Christ’s elevation prior to the creation of man. Ephrem, on the other hand, moved the story to Holy Saturday. In Hades, Death acknowledged Christ as the true first- born whereas Satan rejected any such acclamation. [1] For some time I have pondered the problem of Satan’s fall in early Jewish and Christian sources. My point of origin has been the justly famous account found in the Life of Adam and Eve (hereafter: Life).1 1 See G. Anderson, “The Exaltation of Adam and the Fall of Satan,” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, 6 (1997): 105–34. 3 4 Gary A. Anderson I say justly famous because the Life itself existed in six versions- Greek, Latin, Armenian, Georgian, Slavonic, and Coptic (now extant only in fragments)-yet the tradition that the Life drew on is present in numerous other documents from Late Antiquity.2 And one should mention its surprising prominence in Islam-the story was told and retold some seven times in the Koran and was subsequently subject to further elaboration among Muslim exegetes and storytellers.3 My purpose in this essay is to carry forward work I have already done on this text to the figures of St. -

Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2011 The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A. Matos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Matos, Morgan A., "The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 28. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/28 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Morgan A. Matos July, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Winter Park Master of Liberal Studies Program The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Project Approved: _________________________________________ Mentor _________________________________________ Seminar Director _________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College i Table of Contents Table of Contents i Table of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 1. Historical Development of Satan 4 2. Liturgical Drama 24 3. The Corpus Christi Cycle Plays 32 4. The Morality Play 53 5. Dante, Marlowe, and Milton: Lasting Satanic Impressions 71 Conclusion 95 Works Consulted 98 ii Table of Illustrations 1. Azazel from Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, 1825 11 2. Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness, James Tissot, 1886-1894 13 3. -

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

The Nakedness and the Clothing of Adam and Eve Jeffrey M

The Nakedness and the Clothing of Adam and Eve Jeffrey M. Bradshaw Western art typically portrays Adam and Eve as naked in the Garden of Eden, and dressed in “coats of skin” after the Fall. However, the Eastern Orthodox tradition depicts the sequence of their change of clothing in reverse manner. How can that be? The Eastern Church remembers the accounts that portray Adam as a King and Priest in Eden, so naturally he is shown there in his regal robes.1 Moreover, Orthodox readers interpret the “skins” that the couple wore after their expulsion from the Garden as being their own now-fully-human flesh. Anderson interprets this symbolism to mean that “Adam has exchanged an angelic constitution for a mortal one”2—in other words, they have lost their terrestrial glory and are now in a telestial state. The top panel of the figure above shows God seated in the heavenly council surrounded by angels and the four beasts of the book of Revelation. The second panel depicts, from left to right: Adam and Eve clothed in heavenly robes following their creation; then stripped of their glorious garments and “clothed” only in mortal skin after eating the forbidden fruit; and finally both clad in fig leaf aprons as Eve converses with God. The third panel shows Adam conversing with God, the couple’s expulsion from the walled Garden through a door showing images of cherubim, and their subsequent hardship in the fallen world. Orthodox tradition generally leaves Adam and Eve in their aprons after the Fall and expulsion, seeing them as already having received their “coats of skin” at the time they were clothed in mortal flesh. -

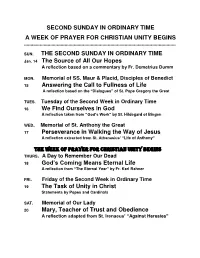

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and Modern Reverberations of an Enigmatic New Testament Prophecy

Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and Modern Reverberations of an Enigmatic New Testament Prophecy Jeffrey M. Bradshaw Figure 1: J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Prophecy of the Destruction of the Temple, 1886-1894 mmediately after His prophecy about the destruction of the temple, Iand just prior to the culminating events of the Passion week, Jesus “went upon the Mount of Olives.”2 Here, in a setting associated with some of His most sacred teachings,3 His apostles “came unto him privately” to question him about the “destruction of the temple, and the Jews,” and the “sign of [His] coming, and of the end of the world, or the destruction of the wicked.” Within this discourse, Jesus gave one of the most controversial prophecies of the New Testament: When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation … stand in the holy place … Then let them which be in Judea flee into the mountains:4 The gospel of Mark is at variance with the wording of the gospel of Matthew, though the two accounts agree in general meaning. Instead of saying that the “abomination of desolation” will “stand in the holy place,”5 72 • Ancient Temple Worship Bradshaw, Standing in the Holy Place • 73 Mark asserts that it will be “standing where it ought not.”6 Luke, writing What [modern exegetes] generally share (although there are, to a Gentile audience that was not as familiar with the temple and its of course, exceptions) is a profound discomfort with the actual customs as were the Jews addressed by Matthew, describes the sign in a interpretations that the ancients came up with — these have more general way, referring to how Jerusalem would be “compassed by little or no place in the way Scripture is to be expounded today. -

Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 10-2007 Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt Minnesota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Zierdt, Ginger L., "Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 60. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Women in History Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt "Wisdom teaches in the light of love, and bids me tell how I was brought into this my gift of vision ..." (Hildegard) Visionary Prodigy Hildegard of Bingen was born in Bermersheim, Germany near Alzey in 1098 to the nobleman Hildebert von Bermersheim and his wife Mechthild, as their tenth and last child. Hildegard was brought by her parents to God as a "tithe" and determined for life in the Order. How ever, "rather than choosing to enter their daughter formally as a child in a convent where she would be brought up to become a nun (a practice known as 'oblation'), Hildegard's parents had taken the more radical step of enclosing their daughter, apparently for life, in the cell of an anchoress, Jutta, attached to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg" (Flanagan, 1989, p. -

Adam's Fall in the Book of Mormon, Second Temple Judaism, and Early Christianity

Adam's Fall in the Book of Mormon, Second Temple Judaism, and Early Christianity Stephen D. Ricks In Father Lehi’s justly famous sermon to his son Jacob, Adam’s transgression is depicted in a remarkably favorable light: the fall was a necessary precondition for mortality, for redemption, and for joy; the serpent gure in the Garden of Eden was Satan, an angel who fell from heaven. The gure of Adam and the story of Adam’s fall square well with the depiction of him in Jewish apocryphal and pseudepigraphic writings, where a positive, if not admiring picture is drawn. But that view diverges sharply from the picture of Adam and his transgression in early Christianity, expressed in denitive form by Augustine, who has a pessimistic outlook on Adam and his fall, a perspective that may have been freighted with his Manichaean baggage. Adam and the Fall in the Book of Mormon The consequences of Adam and Eve’s transgression are outlined succinctly in 2 Nephi 2 and in King Benjamin’s equally famous sermon to the Nephites at the time of Mosiah’s assumption of royal authority, presented in Mosiah 3: 1. A vital precondition for the fall was the expulsion of Satan from the presence of God. According to Lehi, an “angel of God had fallen from heaven; wherefore, he became a devil, having sought that which was evil before God.” Because of his expulsion from the presence of God he “had become miserable forever” and “sought also the misery of all mankind.” Satan tempted Eve to partake of the forbidden fruit, saying, “Ye shall not die, but ye shall be as God, knowing good and evil” (2 Nephi 2:17—18).