Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation in Portuguese Native Dog Breeds: Diversity and Phylogenetic Affinities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

Contact Details Number of Breeds Within FCI Groups List of Breeds

Contact details Last and First name of Judge Borzymowski Jan Address 05-806 Komorów, ul. Mazurska 53, Poland E-mail [email protected] Mobile (+48) 503 482 488 Home phone, Fax (+48) 22 758 03 36, faks 22 758 03 36 ZKwP Branch Warszawa Languages Polish, English Number of breeds within FCI Groups FCI Group FCI group name Level 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs International and other breeds (41/54) 3 Terriers (4/34) International 5 Spitz and primitive types (1/61) International List of breeds FCI Group Breed Level Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs and other breeds 2 Alentejo Mastiff (FCI - 96) International 2 Appenzell Cattle Dog (FCI - 46) International 2 Atlas Mountain Dog - Aidi (FCI - 247) International 2 Bernese Mountain Dog (FCI - 45) International 2 Bosnian and Herzegovinian - Croatian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 355) International 2 Broholmer (FCI - 315) International 2 Bulldog (FCI - 149) International 2 Bullmastiff (FCI - 157) International 2 Castro Laboreiro Dog (FCI - 170) International 2 Caucasian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 328) International 2 Central Asia Shepherd Dog (FCI - 335) International 2 Ciobanesc Romanesc de Bucovina (FCI - 357) International 2 Dogo Argentino (FCI - 292) International 2 Dogue de Bordeaux (FCI - 116) International 2 Entlebuch Cattle Dog (FCI - 47) International 2 Fila Brasileiro (FCI - 225) International 2 Great Dane (FCI - 235) International 2 Great Swiss Mountain Dog (FCI - 58) International 1 FCI Group Breed Level 2 Hovawart (FCI -

Dogo Argentino, Fila Brasileiro, Broholmer, Deutscher Boxer

CACIB DRACULA Special CAC 1 CAC 2 Calificare Crufts 13.09.2014 13.09.2014 13.09.2014 Judge //////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////////////////// Special CAC 3 CAC 4 CACIB 14.09.2014 14.09.2014 CHAMPIONSHIP 14.09.2014 Schnauzers, Tosa, Cão Fila Dogo Argentino, Fila de São Miguel, Cão Brasileiro, Broholmer, da Serra da Estrela, Cão de Deutscher Boxer, Castro Laboreiro, Rafeiro Mastin español, do Alentejo, Grosser Mastin del Pirineo, St. Schweizer Sennenhund, Bernhardshund, Entlebucher Sennenhund, dr.Molnar Zsolt Russkyi Tchiorny Dobermann, Pinschers, /////////////////////////////////////// Terrier, Dogue de Hollandse Smoushound, Gr.I Dagmar Klein Bordeaux, Bulldog, Cane Corso, Coban Hovawart, Leonberger, Köpegi, Jugosloveski Chien de Montagne Ovcarsky Pas-Sarplaninac, des Pyrenees, Chien de Montagne de Appenzeller I'Atlas (Aïdi), Kraski Sennenhund, Ovcar BOG I BOG II Schnauzers, Tosa, Cão Fila de São Miguel, Shar Pei, Deutsche Cão da Serra da Dogge, Dogo Argentino, Fila Estrela, Cão de Castro Mastino Napoletano, Brasileiro, Broholmer, Laboreiro, Rafeiro do Landseer, Deutscher Boxer, Mastin Alentejo, Grosser Kavkazskaïa Ovtcharka, español, Mastin del Schweizer Sredneasiatskaïa Pirineo, St. Sennenhund, Liz-Beth C. Liljeqvist Ovtcharka, Bernhardshund, Russkyi Entlebucher //////////////////////////////////////// Newfoundland, Berner Tchiorny Terrier, Dogue de Sennenhund, Alexey Belkyn Sennenhund ,Rottweiler, Bordeaux, Bulldog, Dobermann, Perro dogo Mallorquin Hovawart, Leonberger, Pinschers, -

Livestock Guardian Dogs Tompkins Conservation Wildlife Bulletin Number 2, March 2017

LIVESTOCK GUARDIAN DOGS TOMPKINS CONSERVATION WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2, MARCH 2017 Livestock vs. Predators TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation PAGE 01 through the use of livestock guardian dogs Livestock vs. Predators: Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation through the use Since humans began domesti- stock and wild predators. Histor- of livestock guardian dogs cating animals, it has been nec- ically, humans have attempted PAGE 04 essary to protect livestock from to resolve this conflict through Livestock Guardian Dogs, wild predators. To this day, pre- a series of predator population an Ancient Tool in dation of livestock is one of the control measures including the Modern Times most prominent global hu- use of traps, hunting, and indis- PAGE 06 man-wildlife conflicts. Interest- criminate and nonselective poi- What Is the Job of a ingly, one of our most ancient soning—methods which are of- Livestock Guardian Dog? domestic companions, the dog, ten cruel and inefficient. was once a predator. One of the greatest chal- PAGE 07 The competition between lenges lies in successfully im- Breeds of Livestock man and wildlife for natural plementing effective measures Guardian Dogs spaces and resources is often that mitigate the negative im- PAGE 08 considered the main source of pacts of this conflict. It is imper- The Presence of Livestock conflict between domestic live- ative to ensure the protection of Guardian Dogs in Chile WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2 MARCH 2017 man and his resources, includ- tion in predators is lower than PAGE 10 ing livestock, without compro- that of the United States, where Livestock in the Chacabuco Valley mising the conservation of the the losses are due to a variety of and the Transition Toward the Future Patagonia National Park native biodiversity. -

AKC Education Webinar Series: FSS/Miscellaneous Questions and Answers

AKC Education Webinar Series: FSS/Miscellaneous Questions and Answers 1. Can an FSS Parent Club offer an ATT Test? If the Parent Club is licensed to hold any event, it may offer an ATT Test. 2. For a domestically evolving breed that started with an independent registry for 20 years, then accepted into UKC for an additional 20 years, can these two be combined to qualify for the 40 years required to be considered into FSS, or must the 40 be done within the same registry body? The history of a breed having a registry for a minimum of 40 years can be merged as described, staff will review to determine if it would meet the parameters required. 3. Does AKC have reciprocity with UKC? AKC has open registration with individual breeds with that are registered by UKC. A breed requesting to be enrolled in the AKC FSS based upon UKC recognition would have reciprocity, if it meets the number of years being in existence, until the breed becomes AKC recognized. At which time the individual breeds may request to keep the studbook open for UKC registered dogs. 4. Is it a good practice to submit all of the required data to AKC in one PDF electronically to FSS as a final submission, once all criteria is met for the ease of processing? The FSS Department keeps track of required data, meeting minutes maybe a PDF, the other requirements need to be in different formats. Breed Standard needs to be a word document, membership list needs to be in an Excel as provided. -

Gundogs Australian National Kennel Council

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD NOTE: Any breed highlighted below has the Pre-1987 Standard GROUP 1 – TOYS GROUP 2 – TERRIERS GROUP 3 - GUNDOGS Affenpinscher KC Airedale Terrier KC Bracco Italiano KC Australian Silky Terrier ANKC American Hairless Terrier AKC Brittany FCI Bichon Frise KC American Staffordshire Terrier AKC Chesapeake Bay Retriever KC Cavalier King Charles Spaniel KC Australian Terrier ANKC Clumber Spaniel KC Chihuahua (Long Coat) KC Bedlington Terrier KC Cocker Spaniel KC Chihuahua (Smooth Coat) KC Border Terrier KC Cocker Spaniel (American) AKC Chinese Crested Dog KC Bull Terrier KC Curly Coated Retriever KC Coton De Tulear (show from 1/3/16) FCI Bull Terrier (Miniature) KC English Setter KC English Springer Spaniel English Toy Terrier (Black & Tan) KC Cairn Terrier KC KC Field Spaniel KC Griffon Bruxellois KC Cesky Terrier FCI Flat Coated Retriever KC Havanese KC Dandie Dinmont Terrier KC German Shorthaired Pointer FCI Italian Greyhound KC Fox Terrier (Smooth) KC German Wirehaired Pointer FCI Japanese Chin KC Fox Terrier (Wire) KC Golden Retriever KC King Charles Spaniel KC German Hunting Terrier FCI Gordon Setter KC Lowchen KC Glen of Imaal Terrier KC Hungarian Vizsla FCI Maltese Irish Terrier KC KC Hungarian Wirehaired Vizsla FCI Miniature Pinscher Jack Russell Terrier KC ANKC Irish Red & White Setter KC Papillon KC Kerry Blue Terrier KC Irish Setter KC Pekingese KC Lakeland Terrier KC Irish Water Spaniel KC Pomeranian KC Manchester Terrier KC Italian Spinone KC Pug KC Norfolk Terrier KC Labrador Retriever KC -

Pharmacovigilance of Veterinary Medicinal Products

a. Reporter Categories Page 1 of 112 Reporter Categories GL42 A.3.1.1. and A.3.2.1. VICH Code VICH TERM VICH DEFINITION C82470 VETERINARIAN Individuals qualified to practice veterinary medicine. C82468 ANIMAL OWNER The owner of the animal or an agent acting on the behalf of the owner. C25741 PHYSICIAN Individuals qualified to practice medicine. C16960 PATIENT The individual(s) (animal or human) exposed to the VMP OTHER HEALTH CARE Health care professional other than specified in list. C53289 PROFESSIONAL C17998 UNKNOWN Not known, not observed, not recorded, or refused b. RA Identifier Codes Page 2 of 112 RA (Regulatory Authorities) Identifier Codes VICH RA Mail/Zip ISO 3166, 3 Character RA Name Street Address City State/County Country Identifier Code Code Country Code 7500 Standish United Food and Drug Administration, Center for USFDACVM Place (HFV-199), Rockville Maryland 20855 States of USA Veterinary Medicine Room 403 America United States Department of Agriculture Animal 1920 Dayton United APHISCVB and Plant Health Inspection Service, Center for Avenue P.O. Box Ames Iowa 50010 States of USA Veterinary Biologic 844 America AGES PharmMed Austrian Medicines and AUTAGESA Schnirchgasse 9 Vienna NA 1030 Austria AUT Medical Devices Agency Eurostation II Federal Agency For Medicines And Health BELFAMHP Victor Hortaplein, Brussel NA 1060 Belgium BEL Products 40 bus 10 7, Shose Bankya BGRIVETP Institute For Control Of Vet Med Prods Sofia NA 1331 Bulgaria BGR Str. CYPVETSE Veterinary Services 1411 Nicosia Nicosia NA 1411 Cyprus CYP Czech CZEUSKVB -

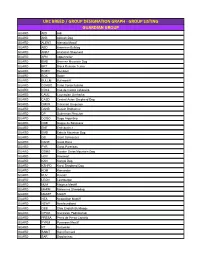

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Contact Details Number of Breeds Within FCI Groups List of Breeds

Contact details Last and First name of Judge Kot Andrzej Address 42-600 Tarnowskie Góry, Torowa 58, Poland E-mail [email protected] Mobile (+48) 601 428 154 Home phone, Fax ZKwP Branch Bytom Languages Polish Number of breeds within FCI Groups FCI Group FCI group name Level 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) (2/52) International 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs International and other breeds (41/54) 6 Scenthounds and related breeds (2/77) International 10 Sighthounds (1/13) International List of breeds FCI Group Breed Level Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) 1 Polish Lowland Sheepdog (FCI - 251) International 1 Tatra Shepherd Dog (FCI - 252) International Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs and other breeds 2 Alentejo Mastiff (FCI - 96) International 2 Appenzell Cattle Dog (FCI - 46) International 2 Atlas Mountain Dog - Aidi (FCI - 247) International 2 Bernese Mountain Dog (FCI - 45) International 2 Bosnian and Herzegovinian - Croatian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 355) International 2 Broholmer (FCI - 315) International 2 Bulldog (FCI - 149) International 2 Bullmastiff (FCI - 157) International 2 Castro Laboreiro Dog (FCI - 170) International 2 Caucasian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 328) International 2 Central Asia Shepherd Dog (FCI - 335) International 2 Ciobanesc Romanesc de Bucovina (FCI - 357) International 2 Dogo Argentino (FCI - 292) International 2 Dogue de Bordeaux (FCI - 116) International 1 FCI Group Breed Level 2 Entlebuch -

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD Judge

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD GROUP 1 - TOYS Judge: Affenpinscher Bourbonnais Pointing Dog * Dachshund (Min. Long) Australian Silky Terrier Bracco Italiano Dachshund (Rabbit Long Bichon Frise Brittany Haired) * Bolognese * Chesapeake Bay Retriever Dachshund (Smooth) Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Clumber Spaniel Dachshund (Min. Smooth) Chihuahua (Long Coat) Cocker Spaniel Dachshund (Rabbit Smooth Chihuahua (Smooth Coat) Cocker Spaniel (American) Haired) * Chinese Crested Dog Curly Coated Retriever Dachshund (Wire) Continental Toy Spaniel Deutch Stichelhaar * Dachshund (Min. Wire) (Papillon) Drentsche Partridge Dog * Dachshund (Rabbit Wire Continental Toy Spaniel English Setter Haired) * (Phalene) * English Springer Spaniel Deerhound Coton De Tulear Field Spaniel Drever * Griffon Belge * Flat Coated Retriever Fawn Brittany Griffon * English Toy Terrier (Black & French Pointing Dog Gascogne Finnish Hound * Tan) Type * Finnish Spitz Griffon Bruxellois French Pointing Dog Pyrenean Foxhound Havanese Type * Gascon Saintongeois * Italian Greyhound French Spaniel * German Hound * Japanese Chin French Water Dog * Grand Basset Griffon King Charles Spaniel Frisian Pointing Dog * Vendeen Kromforhlander * Frisian Water Dog * Grand Griffon Vendeen * Lowchen German Shorthaired Pointer Great Anglo French-White & Maltese German Wirehaired Pointer Black Hound * Miniature Pinscher German Spaniel * Great Anglo-French Tri Colour Hound * Pekingese Golden Retriever Great Anglo-French White & Petit Brabancon * Gordon Setter Orange Hound * Pomeranian -

New Proposed AKC Group from Realignment Committee- Group 10

AKC Group Realignment December, 2011 The American Kennel Club is proposing group realignment and expanding the number of conformation groups from the current 7 to 11. If you would like to read the list of groups and the dogs proposed to go into those groups you can find it at this link: http://www.cspca.com/Realignment/Suggested%20Breed%20List.pdf The Realignment Committee has placed the Chinese Shar-Pei in the Working Spitz group; however we can let AKC know if we had rather be in some other group. Dogs are placed in groups according to common features, traits, skills, natural instincts, ancestry etc. If the Group Realignment passes, then whichever group we end up in will be the group that we will stay in for a long time to come. It is very important that we choose wisely as to what is in the best interest of our breed. It would also be wise to consider what is to be gained by moving from our current group. What do we stand to lose by moving to a new group? We should only move to a new group in order to improve our breed and not for anyone’s personal gain. I have made a photo chart of the different groups that have been proposed by people for our breed. Please study the groups carefully before you vote on the group that you feel would best represent our breed New Proposed AKC Group from Realignment Committee- Group 10: Non-Sporting The breeds in the Non-Sporting Group are a varied collection in terms of size, coat, personality and overall appearance.