View Pdfs of the Exhibit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Public Art Museum: Formation of Its Prevailing Attitudes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1982 The American Public Art Museum: Formation of its Prevailing Attitudes Marilyn Mars Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AMERICAN PUBLIC ART MUSEUM: FORMATION OF ITS PREVAILING ATTITUDES by MARILYN MARS B.A., University of Florida, 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of d~rts RICHMOND, VIRGINIA December, 1982 INTRODUCTION In less than one hundred years the American public art museum evolved from a well-intentioned concept into one of the twentieth century's most influential institutions. From 1870 to 1970 the institution adapted and eclipsed its European models with its didactic orientation and the drive of its founders. This striking development is due greatly to the ability of the museum to attract influential and decisive leaders who established its attitudes and governing pol.icies. The mark of its success is its ability to influence the way art is perceived and remembered--the museum affects art history. An institution is the people behind it: they determine its goals, develop its structure, chart its direction. -

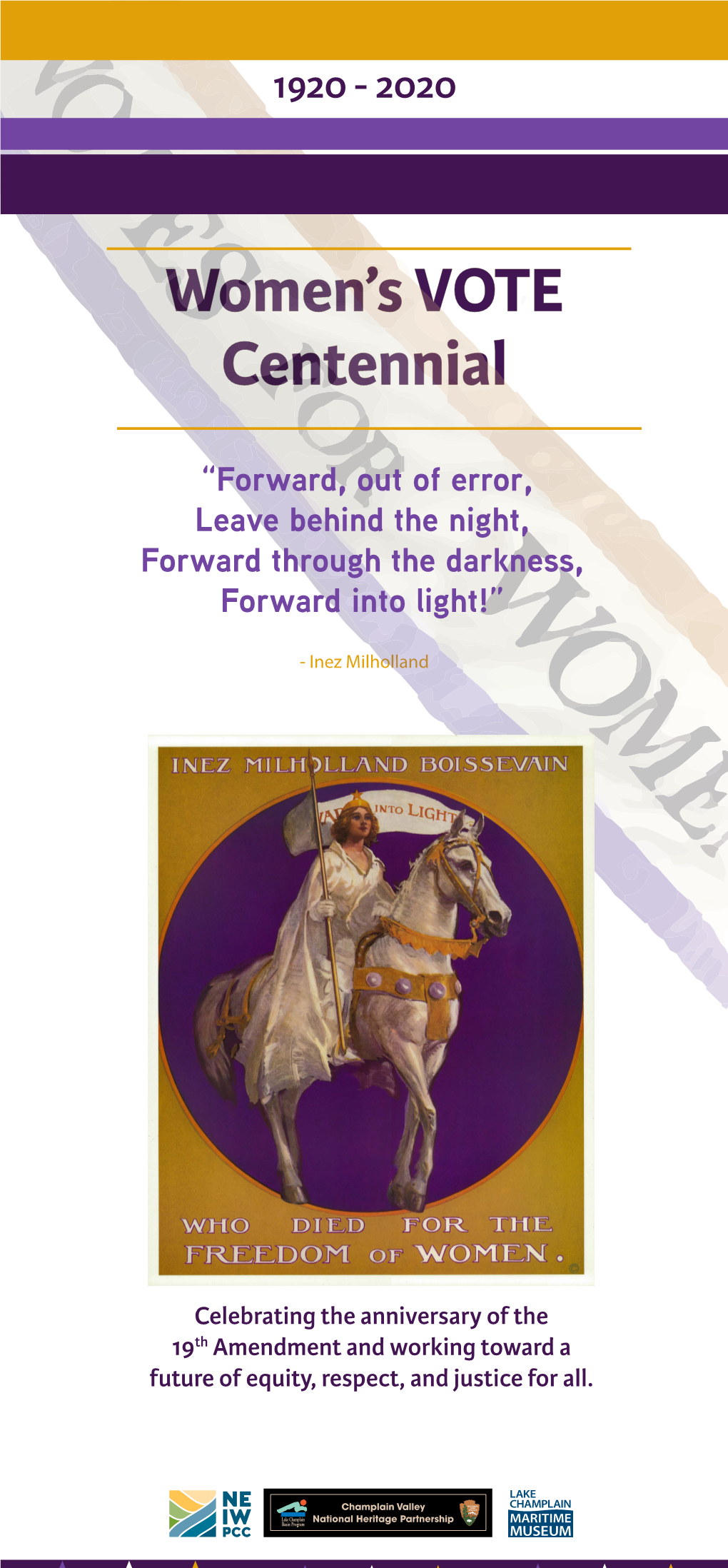

Inez Milholland “Gave Her Life to the Fight for Suffrage” August 6, 1886 – November 25, 1916

Inez Milholland “Gave her life to the fight for suffrage” August 6, 1886 – November 25, 1916 Inez Milholland was born on August 6, 1886 in Brooklyn, New York to wealthy parents. Milholland grew up in New York City and London. She met militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst in England, who converted Milholland into a political radical, a transfor- mation that would define her life. Milholland attended Vassar College, where she continued to be politically active. The school had a rule that banned discussion of suffrage on campus, so Milholland organized meetings in a local cemetery. Milholland was also very active in extracurriculars at school, performing as Romeo in Romeo and Juliet, as well as numerous roles in other productions. She was also a member of the Current Topics Club, the German Club, the debate team, and the unrecognized but very present Socialist Club. Additionally, Milholland played basketball, tennis, golf, and field hockey. She broke Vassar’s shot-put record in her sophomore year and won the college cup for best all-around athlete as a junior. After her graduation from Vassar in 1909, Milholland began to work as a suffrage orator in New York City, also advocating for women’s labor rights and was arrested for picketing alongside female workers during strikes in 1909 and 1910. During these strikes, Milholland used her status and resources as a mem- ber of the upper-class to pay bail for strikers and organize fundraisers. As a woman, she was rejected from several law schools but earned a law degree from New York University in 1912. -

Alice Paul: “I Was Arrested, of Course…”

Trusted Writing on History, Travel, Food and Culture Since 1949 BEFORE THE COLORS FADE Alice Paul: “I Was Arrested, Of Course…” An interview with the famed suffragette, Alice Paul Robert S. Gallagher February 1974, Volume 25, Issue 2 American women won the right to vote in 1920 largely through the controversial efforts of a young Quaker named Alice Paul. She was born in Moorestown, New Jersey, on January 11, 1885, seven years after the woman-suffrage amendment was first introduced in Congress. Over the years the so-called Susan B. Anthony amendment had received sporadic attention from the national legislators, but from 1896 until Miss Paul’s dramatic arrival in Washington in 1912 the amendment had never been reported out of committee and was considered moribund. As the Congressional Committee chairman of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Miss Paul greeted incoming President Woodrow Wilson with a spectacular parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. Congress soon began debating the suffrage amendment again. For the next seven years— a tumultuous period of demonstrations, picketing, politicking, street violence, beatings, jailings, and hunger strikes—Miss Paul led a determined band of suffragists in the confrontation tactics she had learned from the militant British feminist Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst. This unrelenting pressure on the Wilson administration finally paid off in 1918, when an embattled President Wilson reversed his position and declared that woman suffrage was an urgently needed “war measure.” The woman who, despite her modest disclaimers, is accorded major credit for adding the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution is a 1905 graduate of Swarthmore College. She received her master’s degree (1907) and her Ph.D. -

PIONEERS of WOMEN’S RIGHTS in MANHATTAN Gale A

A WALKING TOUR PIONEERS OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN MANHATTAN Gale A. Brewer MANHATTAN BOROUGH PRESIDENT Brewer_WomensHistory_Final.indd 1 2/25/20 4:08 PM One Hundred Years of Voting A century has passed since American suffragists girded for their final push to win the ballot for women in every corner of the United States. Under the skilled and persistent direction of Carrie Chapman Catt, and spurred by the energy of Alice Paul’s National Woman Party, the 19th Amendment won approval on August 26, 1920. In this pamphlet, we find reminders of the struggles and achievements of New York women who spoke, marched, and even fought for the vote and the full panoply of rights. These were women who marched to Albany in the winter, or demonstrators who were jailed for their protests in Washington. Crystal Eastman, a young activist, spoke a large truth when she said, after ratification, “Now we can begin.” To complete one task is to encounter the next. Indeed, even after a hundred years we must still seek to complete the work of attaining women’s equality. Sincerely, Gale A. Brewer, Manhattan Borough President Brewer_WomensHistory_Final.indd 2 2/25/20 4:08 PM Sojourner Truth Preacher for Abolition and Suffrage Old John Street Chapel 1 Sojourner Truth was born Isabella Baumgold and lived as a Dutch-speaking slave in upstate New York. With difficulty, she won her freedom, moved to New York City, and joined the Methodist Church on John Street. She then changed her name to Sojourner Truth and spent the rest of her long life speaking against slavery and for women’s rights. -

Objectified Through an Implied Male Gaze

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist Ganus, Linda Carol 2017 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist by Linda C. Ganus A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History Lehigh University August 4, 2017 © 2017 Copyright Linda C. Ganus ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of (Arts/Sciences) in (Department/Program). “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist Linda Ganus Date Approved Dr. John Pettegrew Dr. Roger Simon iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. John Pettegrew, Chair of the History Department at Lehigh University. In addition to being a formidable researcher and scholar, Prof. Pettegrew is also an unusually empathetic teacher and mentor; tireless, positive, encouraging, and always challenging his students to strive for the next level of excellence in their critical thinking and writing. The seeds for this project were sown in Prof. Pettegrew’s Intellectual U.S. History class, one of the most influential classes I have had the pleasure to take at Lehigh. I am also extremely grateful to Dr. -

Alice Paul and Her Quaker Witness

Alice Paul and her Quaker witness by Roger Burns June 2, 2019 Please share this article with other Friends. Sharing this article is allowed and encouraged. See the copyright notice on the reverse side of this cover page. About the author: Roger Burns lives in Washington, DC. Like the subject of this article, he is a street activist as well as a Friend, being active in the affairs of his neighborhood and his city. Roger has a mystical bent. Several years ago during an Experiment With Light workshop he received a strong leading to promote racial reconciliation. Since then his major focus in the realm of social witness is on race issues. He has helped to manage a weekly public discussion about race that takes place at the church-run Potter's House Cafe in Washington. He serves on the Peace and Social Justice Committee of the Bethesda Friends Meeting. Roger was for a time a history major at college, and he later earned bachelor's and master's degrees in economics. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the following for assisting with this article: Lucy Beard and Kris Myers of the Alice Paul Institute; the Bethesda Friends Meeting of Maryland; the many Friends of the Westbury Quaker Meeting; Alex Bell for going above and beyond; Ralph Steinhardt; Maya Porter; Rene Lape; June Purvis; David Zarembka; Stephanie Koenig. This article is available on the Internet at: http://www.bethesdafriends.org/Alice-Paul-and-her-Quaker-witness-2019.pdf Published by Roger Burns, 2800 Quebec St. NW, Washington, DC 20008 United States of America Phone: 202-966-8738 Email: [email protected] Date: June 2, 2019 COPYRIGHT NOTICE: © 2019 by Roger Burns. -

Chefs D'œuvre De La Peinture Française Du Clark / Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark

Alison McQueen exhibition review of Il était une fois...l'impressionisme: Chefs d'œuvre de la peinture française du Clark / Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Citation: Alison McQueen, exhibition review of “Il était une fois...l'impressionisme: Chefs d'œuvre de la peinture française du Clark / Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), http:// www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring13/mcqueen-reviews-once-upon-a-time-impressionism. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. McQueen: Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Il était une fois...l'impressionisme: Chefs d'œuvre de la peinture française du Clark / Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal October 9, 2012 – January 20, 2013 Previous venues: Palazzo Reale Milan, Italy March 2 – June 19, 2011 Musée des Impressionnismes Giverny, France July 12 – October 31, 2011 CaixaForum Barcelona, Spain November 18, 2011 – February 12, 2012 Kimbell Art Museum Fort Worth, Texas March 4 – June 17, 2012 Royal Academy of Arts London, UK July 7 – September 23, 2012 It will also travel to Japan, China, and South Korea in 2013–2014. What is at stake in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute’s re-branding of itself? The exhibition and catalogue of nineteenth-century French art from the Williamstown-based institute that is currently traveling to three continents presents a new history to unsuspecting visitors: Sterling Clark, founder of the eponymous institute, was an autonomous collector who selected and acquired works with complete independence. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman's Party Suffrage

TACTICS AND TECHNIQUES OF THE NATIONAL WOMAN’S PARTY SUFFRAGE CAMPAIGN Introduction Founded in 1913 as the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was instrumental in raising public awareness of the women’s suffrage campaign. The party successfully pressured President Woodrow Wilson, members of Congress, and state legislators to support passage of a 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (known popularly as the “Anthony” amendment) guaranteeing women nationwide the right to vote. The NWP also established a legacy defending the exercise of free speech, free assembly, and the right to dissent–especially during wartime. (See Historical Overview) The NWP had only 50,000 members compared to the 2 million members claimed by its parent organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Nonetheless, the NWP effectively commanded the attention of politicians and the public through its aggressive agitation, relentless lobbying, creative publicity stunts, repeated acts of nonviolent confrontation, and examples of civil disobedience. The NWP forced the more moderate NAWSA toward greater activity. These two groups, as well as other suffrage organizations, rightly claimed victory on August 26, 1920, when the 19th Amendment was signed into law. The tactics used by the NWP to accomplish its goals were versatile and creative. Its leaders drew inspiration from a variety of sources–including the British suffrage campaign, American labor activism, and the temperance, antislavery, and early women’s rights campaigns in the United States. Traditional lobbying and petitioning were a mainstay of party members. From the beginning, however, conventional politicking was supplemented by other more public actions–including parades, pageants, street speaking, demonstrations, and mass meetings. -

Dedication Planned for New National Suffrage Memorial

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY ALLIANCE Women Win the Vote Before1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 1920 & Beyond You're Invited! Celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote Learn What’s Happening in Your State and Online HROUGHOUT 2020, Americans will celebrate the Tcentennial of the extension of the right to vote to women. When Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919, and 36 states ratified it by August 1920, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Now there are local, state and national centennial celebrations in the works including shows and © Trevor Stamp © Trevor parades, parties and plays, films The Women’s Suffrage Centennial float in the Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, was seen by millions on January 1, 2020. On the float were the and performers, teas and more. descendants of suffragists including Ida B. Wells, Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Ten rows of Learn more, get involved, enjoy the ten women in white followed, waving to the crowd. Trevor Stamp photo. activities, and recognize as never before that women’s hard fought Dedication Planned for New achievements are an important part of American history. National Suffrage Memorial HE TURNING POINT Suffra- were jailed over 100 years ago. This gist Memorial, a permanent marked a critical turning point in suffrage Inside This Issue: tribute to the American women’s history. Great Resources T © Robert Beach suffrage movement, will be unveiled on Spread over an acre, the park-like A rendering of the Memorial August 26, 2020 in Lorton, Virginia. -

Centennial Events Planned in Communities Across the Country

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY ALLIANCE Women Win the Vote Before1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 1920 & Beyond You're Invited! Celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote Learn What’s Happening in Your State HROUGHOUT 2019 and 2020, Americans will Tcelebrate the centennial of the extension of the right to vote to women. When Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919, and 36 states ratified it by August 1920, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Now there are local, state and national centennial celebrations in the works including shows and parades, parties and plays, films © Ann Altman and performers, teas and more. Learn more, get involved, enjoy the activities, and recognize as never Centennial Events Planned in before that women’s hard fought achievements are an important part Communities Across the Country of American history. OR MORE THAN a year, women amendment in June 2019, some states Inside This Issue: throughout the country have been have been commemorating their Fmeeting, planning and organizing legislature’s ratification 100 years ago Great Resources for the 2020 centennial of women with official proclamations, historical winning the right to vote. The focal reenactments, exhibits, events and more. Tahesha Way, New Jersey Secretary of 100 Suffragists point is passage of the 19th Amendment, There is a wealth of material available State, at the Alice Paul Institute during a Spring 2019 press conference on state African American celebrated on Equality Day, August 26, here and online which will help you stay suffrage centennial plans. -

"Fine Dignity, Picturesque Beauty, and Serious Purpose": The

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2015 "Fine Dignity, Picturesque Beauty, and Serious Purpose": The Reorientation of Suffrage Media in the Twentieth Century Emily Scarbrough Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Scarbrough, Emily, ""Fine Dignity, Picturesque Beauty, and Serious Purpose": The Reorientation of Suffrage Media in the Twentieth Century" (2015). Masters Theses. 2033. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2033 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School~ EAs'ffJQ>J lmNOllS UNWERS!TY" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis.