Friulian Language in Education in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workshop on Transboundary Wildlife Management

ALPBIONET2030 Integrative Alpine wildlife and habitat management for the next generation REPORT Workshop on Transboundary wildlife management 10 October 2017, Trenta, Triglav National Park, Slovenia (Alpbionet2030 – Work Package 2) Integrative Alpine wildlife and habitat management for the next generation A workshop to discuss tactics and devise actions for transboundary wildlife management between the wildlife managers of Transboundary Ecoregion Julian Alps, defined as the sum of Triglav Hunting Management Area and Gorenjska Hunting Management Area (Slovenia) and Tarvisiano Hunting District (Italy) with their core protected areas of Triglav National Park and Prealpi Giulie Nature Park, was held at the conference facilities of the “Dom Trenta” National Park house in Trenta. This Workshop is one of the activities of WP T.2 of the Alpbionet2030 project co- financed by the EU Alpine Space Programme. INTRODUCTION The behaviour and habitat use of animals can be strongly affected by hunting methods and wildlife management strategies. Hunting and wildlife management therefore have an influence on ecological connectivity. Lack of consistency in wildlife management between regions can cause problems for population connectivity for some species, particularly those with large home ranges, (e.g. some deer and large carnivores). Hunting seasons, feeding (or lack thereof), the existence of resting zones where hunting is prohibited, legal provisions for wildlife corridors, even administrative authority for wildlife management differ from one Alpine country to another. The Mountain Forest Protocol of the Alpine Convention (1996) asks parties to harmonise their measures for regulating the game animals, but so far this is only happening in a few isolated instances. Thus, to further the goals of ecological connectivity, ALPBIONET2030 aims coordinate wildlife management in selected pilot areas. -

Gortani Giovanni (1830-1912) Produttore

Archivio di Stato di Udine - inventario Giovanni Gortani di S Giovanni Gortani Data/e secc. XIV fine-XX con documenti anteriori in copia Livello di descrizione fondo Consistenza e supporto dell'unità bb. 54 archivistica Denominazione del soggetto Gortani Giovanni (1830-1912) produttore Storia istituzionale/amministrativa Giovanni Gortani nasce ad Avosacco (Arta Terme) nel 1830. Si laurea in giurisprudenza a del soggetto produttore Padova e in seguito combatte con i garibaldini e lavora per alcuni anni a Milano. Rientrato ad Arta, nel 1870 sposa Anna Pilosio, da cui avrà sette figli. Ricopre numerosi incarichi, tra cui quello di sindaco di Arta e di consigliere provinciale, ma allo stesso tempo si dedica alla ricerca storica e alla raccolta e trascrizione di documenti per la storia del territorio della Carnia. Gli interessi culturali di Gortani spaziano dalla letteratura all'arte, dall'archeologia alla numismatica. Pubblica numerosi saggi su temi specifici e per occasioni particolari (opuscoli per nozze, ingressi di parroci) e collabora con il periodico "Pagine friulane". Compone anche opere letterarie e teatrali. Muore il 2 agosto 1912. Modalità di acquisizione o La raccolta originaria ha subito danni e dispersioni durante i due conflitti mondiali. versamento Conservata dal primo dopoguerra nella sede del Comune di Arta, è stata trasferita nel 1953 presso la Biblioteca Civica di Udine e successivamente depositata in Archivio di Stato (1959). Ambiti e contenuto Lo studioso ha raccolto una notevole quantità di documenti sulla storia ed i costumi della propria terra, la Carnia, in parte acquisiti in originale e in parte trascritti da archivi pubblici e privati. Criteri di ordinamento Il complesso è suddiviso in tre sezioni. -

Sito Inquinato Di Interesse Nazionale Laguna Di Grado E Marano: Determinazione Dei Valori Di Fondo Nei Suoli Agricoli Prospicienti Il Sito Di Interesse Nazionale

Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione dell'Ambiente del Friuli - Venezia Giulia Dipartimento Provinciale di Udine Servizio Tematico Analitico Via Colugna 42 - 33100 Udine tel. 0432 – 493711- 493764 - fax 0432 – 493778 – 546776 Sito Inquinato di Interesse Nazionale Laguna di Grado e Marano: determinazione dei valori di fondo nei suoli agricoli prospicienti il Sito di Interesse Nazionale Ottobre 2007 Indice Indice .........................................................................................................................................1 1 Introduzione......................................................................................................................2 2 Aspetti fisici generali ........................................................................................................3 2.1 Aspetti geopedologici.................................................................................................3 2.2 Assetto planoaltimetrico.............................................................................................4 2.3 Reticolo idrografico....................................................................................................4 2.4 La bonifica idraulica...................................................................................................4 2.5 Aspetti idrogeologici ..................................................................................................5 3 Obiettivo dello Studio.......................................................................................................7 -

Pagamenti 3 Trimestre 2020

PUBBLICAZIONE PAGAMENTI EFFETTUATI NEL 3' TRIMESTRE 2020 - D.LGS. 97/2014 ESERCIZIO SIOPE DESCRIZIONE SIOPE BENEFICIARIO PAGAMENTO COMUNE SEDE BENEFICIARIO IMPORTO EURO 2020 1010101002 Voci stipendiali corrisposte al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 133.659,08 2020 1010101004 Indennità ed altri compensi, esclusi i rimborsi spesa per missione, corrisposti al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 281,23 2020 1010101004 Indennità ed altri compensi, esclusi i rimborsi spesa per missione, corrisposti al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 6.342,43 2020 1010102002 Buoni pasto DAY RISTOSERVICE S.P.A. BOLOGNA 1.487,62 2020 1010102002 Buoni pasto UNIONE TERRITORIALE INTERCOMUNALE - MEDIOFRIULI BASILIANO 5.008,31 2020 1010201001 Contributi obbligatori per il personale INPDAP - CONTRIBUTO CPDEL 22.346,95 2020 1010201001 Contributi obbligatori per il personale EX INADEL - INPDAP 547,52 2020 1010201003 Contributi per indennità di fine rapporto EX INADEL - INPDAP 2.595,33 2020 1010202001 Assegni familiari DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 798,60 2020 1020101001 Imposta regionale sulle attività produttive (IRAP) REGIONE AUTONOMA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA TRIESTE 9.601,56 2020 1020102001 Imposta di registro e di bollo AGENZIA DELLE ENTRATE ROMA 10,00 2020 1020109001 Tassa di circolazione dei veicoli a motore (tassa automobilistica) ECONOMO COMUNALE BASILIANO 442,25 2020 1020199999 Imposte, tasse e proventi assimilati a carico dell'ente n.a.c. TELECOM ITALIA S.P.A. -

Associazione Culturale Musicale Di Bertiolo “Filarmonica La Prime Lûs 1812”

Associazione Culturale Musicale di Bertiolo “Filarmonica la Prime Lûs 1812” 6th INTERNATIONAL CONTEST OF COMPOSITION FOR BAND “LA PRIME LÛS” BERTIOLO, 16th -17th DECEMBER 2017 The Cultural Musical Association of Bertiolo “Filarmonica La Prime Lûs 1812” in co-operation with the town of Bertiolo, the Province of Udine, the Region Friuli Venezia Giulia, the ANBIMA, and the Pro Loco Risorgive Medio Friuli organizes the 6th International Contest of Composition for Band “La Prime Lûs” REGULATION Art. 1 The 6th International Contest of Composition for Band “La Prime Lûs” will take place in Bertiolo, Udine, Italy on the 16th and 17th December 2017, at the headquarters of the Association. Art. 2 The contest is open only to original compositions for every genre of band, which will have to respect the organic according with article 3 of the present regulation, including the pieces for soloists – instrumental or/and vocal – and band. Electronic instruments are not allowed in the compositions. Art. 3 The compositions will be divided in three (3) categories and the prizes will be awarded following these categories, according to the international classification adopted by the publishing houses. The compositions, for each category, must respect the length, difficulty and organic listed below: FIRST CATEGORY Length: minimum 8 minutes – maximum 12 minutes; Difficulty 4 Instrumentation: piccolo, flute (1 st and 2nd); oboe (1st and 2nd); English horn (optional); bassoon (1st and 2nd); small clarinet mib; clarinets sib (1st , 2nd and 3rd), contralto clarinet mib; bass clarinet sib; contralto sax mib (1st and 2nd); tenor sax sib (1st and 2nd); baritone sax mib; trumpets sib (1st , 2nd and 3rd); trombone (1st , 2nd and 3rd); bass trombone (optional); F-horns (1 st, 2nd ,3rd and 4th); baritone flugelhorn – euphonium (1st and 2nd); tuba (1 st and 2nd); string double- bass (optional); timpani (maximum 4 boilers); percussions: drum, bass drum, cymbals and other Regulation of 6th International Contest of Composition of Band “La Prime Lûs” Bertiolo 16-17 December 2017 Pag. -

Raccolta Sacchetti Verdi

Comuni di: Bertiolo, Buttrio, Basiliano, Camino al Tagliamento, Campoformido, Codroipo, Corno di Rosazzo, Martignacco, Moimacco, Mortegliano, Nimis, Pasian di Prato, Pavia di Udine, Pozzuolo del Friuli, Pradamano, Remanzacco, Rivignano, San Giovanni al Natisone, Sedegliano, Varmo SERVIZIO DI RACCOLTA PORTA A PORTA DI PANNOLINI, PANNOLONI E TRAVERSE SALVA-LETTO Per rispondere a concrete esigenze dell’utenza, è stato istituito un servizio integrativo di raccolta porta a porta dei pannolini usati conferiti in appositi contenitori (sacchetti verdi). Cosa è possibile raccogliere nei sacchetti verdi? Pannolini, pannoloni e traverse salva-letto Quando vengono raccolti i sacchetti verdi? Una volta a settimana, nelle seguenti giornate: COMUNE GIORNATA DI RACCOLTA Campoformido Moimacco Lunedì Remanzacco Buttrio Corno di Rosazzo Martedì Pavia di Udine San Giovanni al Natisone Camino al Tagliamento Bertiolo Mercoledì Basiliano Rivignano Martignacco Giovedì Nimis Mortegliano Pasian Di Prato Venerdì Pozzuolo Del Friuli Pradamano Codroipo Sedegliano Sabato Varmo In caso di festività, il servizio non verrà effettuato. Si ricorda che è sempre possibile raccogliere i pannolini nei sacchi gialli e conferirli nella giornata di raccolta del secco residuo. Quando e dove bisogna posizionare i sacchetti verdi? I sacchetti verdi vanno posizionati nel punto di abituale conferimento, dalle ore 20.00 alle ore 24.00 della sera precedente il giorno di raccolta. Avvertenze 1. All’interno del sacchetto verde è possibile conferire esclusivamente pannolini, pannoloni e traverse salva-letto. 2. Il sacchetto, chiuso con l’apposito laccio, va posizionato su suolo pubblico esclusivamente negli orari e nella giornata indicati. Attenzione! I sacchetti verdi non vengono raccolti nella giornata di raccolta del secco residuo. A&T 2000 S.p.A. -

30-Furlanetto Et Al

GRAVIMETRIC AND MICROSEISMIC CHARACTERIZATION OF THE GEMONA (NE ITALY) ALLUVIAL FAN FOR SITE EFFECTS ESTIMATION Furlanetto Eleonora, University of Trieste - Dip. Scienze della Terra, Trieste, Italy Costa Giovanni, University of Trieste - Dip. Scienze della Terra, Trieste, Italy Palmieri Francesco, OGS, Trieste, Italy Delise Andrea, University of Trieste - Dip. Scienze della Terra, Trieste, Italy Suhadolc Peter, University of Trieste - Dip. Scienze della Terra, Trieste, Italy CS5 :: Poster :: Thursday - Friday :: Level 2 :: P533B The urban area of Gemona (NE Italy) is mainly built on alluvial fan sediments that contributed to the destruction of the city during the Friuli earthquake, May-September 1976. Three accelerometric stations of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Accelerometric Network, run by the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Trieste, in collaboration with the Civil Defence of FVG, are set in Gemona for site effects estimation purposes. Using weak motion recordings of these stations, we are able to derive the H/V spectral ratio and also to apply the reference site technique. The result of these elaborations shows different resonant frequencies in the two sites (one on the fan, one on the sedimentary basin), when excited by the same event, and also different resonance frequencies at the same site when excited by different events. This can be explained with 2D or 3D site effects modelling, that requires, however, the characterization of the local subsoil structures, in particular the sediment-bedrock contact. We use gravimetric data to characterize a model with a homogeneous sedimentary layer of variable thickness along five selected profiles. The models are elaborated using the residual Bouguer anomaly and, as a constraint, three boreholes that reach the bedrock, geological outcrops and intersection points on the profiles. -

Friuli Venezia Giulia: a Region for Everyone

EN FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA: A REGION FOR EVERYONE ACCESSIBLE TOURISM AN ACCESSIBLE REGION In 2012 PromoTurismoFVG started to look into the tourist potential of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region to become “a region for everyone”. Hence the natural collaboration with the Regional Committee for Disabled People and their Families of Friuli Venezia Giulia, an organization recognized by Regional law as representing the interests of people with disabilities on the territory, the technical service of the Council CRIBA FVG (Regional Information Centre on Architectural Barriers) and the Tetra- Paraplegic Association of FVG, in order to offer experiences truly accessible to everyone as they have been checked out and experienced by people with different disabilities. The main goal of the project is to identify and overcome not only architectural or sensory barriers but also informative and cultural ones from the sea to the mountains, from the cities to the splendid natural areas, from culture to food and wine, with the aim of making the guests true guests, whatever their needs. In this brochure, there are some suggestions for tourist experiences and accessible NATURE, ART, SEA, receptive structures in FVG. Further information and technical details on MOUNTAIN, FOOD our website www.turismofvg.it in the section AND WINE “An Accessible Region” ART AND CULTURE 94. Accessible routes in the art city 106. Top museums 117. Accessible routes in the most beautiful villages in Italy 124. Historical residences SEA 8. Lignano Sabbiadoro 16. Grado 24. Trieste MOUNTAIN 38. Winter mountains 40. Summer mountains NATURE 70. Nature areas 80. Gardens and theme parks 86. On horseback or donkey 90. -

Introduction: Castles

Introduction: Castles Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the new invasions that were threatening Europe, led the powerful feudal lords to build castles and fortresses on inaccessible heights, at the borders of their territories, along the main roads and ri- vers’ fords, or above narrow valleys or near bridges. The defense of property and of the rural populations from ma- rauding invaders, however, was not the only need during those times: the widespread banditry, the local guerrillas between towns and villages that were disputing territori- es and powers, and the general political crisis, that inve- sted the unguided Italian kingdom, have forced people to seek safety and security near the forts. Fortified villages, that could accommodate many families, were therefore built around castles. Those people were offered shelter in exchange of labor in the owner’s lands. Castles eventually were turned into fortified villages, with the lord’s residen- ce, the peasants homes and all the necessary to the community life. When the many threats gradually ceased, castles were built in less endangered places to bear witness to the authority of the local lords who wanted to brand the territory with their power, which was represented by the security offered by the fortress and garrisons. Over the centuries, the castles have combined several functions: territory’s fortress and garrison against invaders and internal uprisings ; warehouse to gather and protect the crops; the place where the feudal lord administered justice and where horsemen and troops lived. They were utilised, finally, as the lord’s and his family residence, apartments, which were gradually enriched, both to live with more ease, and to make a good impression with friends and distinguished guests who often stayed there. -

Comune Di Torreano

COMUNE DI TORREANO ESERCIZIO FINANZIARIO 2017 RELAZIONE DELL’ORGANO ESECUTIVO Art. 151, comma 6, D.Lgs. 267/2000 CONTO CONSUNTIVO ESERCIZIO FINANZIARIO 2017 RELAZIONE ILLUSTRATIVA DELLA GIUNTA COMUNALE L’art. 151 del D.Lgs. 267/2000, comma 6°, prescrive che al rendiconto dei Comuni sia allegata una relazione della Giunta sulla gestione che esprime le valutazioni di efficacia dell'azione condotta sulla base dei risultati conseguiti. Anche l’art. 231 del D.Lgs. 267/2000 prescrive: “La relazione sulla gestione è un documento illustrativo della gestione dell'ente, nonché dei fatti di rilievo verificatisi dopo la chiusura dell'esercizio, contiene ogni eventuale informazione utile ad una migliore comprensione dei dati contabili, ed è predisposto secondo le modalità previste dall'art. 11, comma 6, del decreto legislativo 23 giugno 2011, n. 118, e successive modificazioni”. La presente relazione è quindi redatta per soddisfare il precetto legislativo, per fornire dati di ragguaglio sulla produzione dei servizi pubblici e per consentire una idonea valutazione della realizzazione delle previsioni di bilancio. Questo Comune al 31.12.2017 conta n. 2129 abitanti residenti nel capoluogo e nelle frazioni di: Reant, Masarolis, Canalutto, Costa, Ronchis, Montina, Prestento e Togliano Il Comune di Torreano si caratterizza per le modeste dimensioni geografiche e demografiche, per la montuosità del territorio e per l'insediamento sullo stesso di un'economia in cui vi è una distribuzione piuttosto omogenea delle varie attività (agricola, industriale, artigianale e terziaria). Particolarmente conosciuta è l'attività della lavorazione della pietra Piasentina. Nel corso del 2017 il Comune di Torreano ha visto ulteriormente ridurre il personale in servizio a seguito della cessazione per quiescenza di un proprio dipendente. -

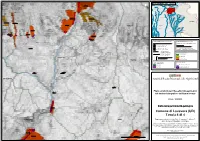

Comune Di Lusevera (UD) Tavola 4 Di 4

!< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< .! INAmQpezUzo ADRAM.!ENTO DEL.!LA TA.!VOLA Tolmezzo Moggio UdineseChiusaforte 0300510300A .! 0302041600 Cavazzo Carnico !< ± 1 2 0300510600 !< .! .!Gemona del Friuli !< Trasaghis .! 3 Lusevera 0302042500 !< 4 0302042400 .! !< Travesio .! Attimis 0302041300 .! !< !< .! Pulfero 0300510500 San Daniele del Friuli !<0300510500-CR 0300512300-CR .! .! 0302041500 Spilimbergo !< Povoletto .! !< 0302121700 Cividale del Friuli SLOVENIA 0302040000 !< !< .! 0302042400-CR !< UDINE 0302042500-CR 0302040100 0302039800 0302041200 !< !< 0300510200 !< 0300512300 .! !< 0300510600 !< Sedegliano 0302041400 0302039900 0302066800 0302121603 !< !< !< !< 0302040300 .! !< .! Codroipo San Giovanni al Natisone 0302040400 !< 0302040500 0302041000 0302058900 !< .! 0302040700 GORIZIA 0300510200 !< !< !<0300510400 0302127100 0302042900 !< .! 03020409000302041100 03020!<40200 !< !< !< !< 2 Palmanova .! 0302039600 Gradisca d'Isonzo !< 0302040800 !< 0302040600 0302039600 0302042900 !< !< 0302042600 !< !< 0300510400A .! .!Latisana San Canzian d'Isonzo 0302127300 0302121601 !< !< !< 0300510400 !< 0302127200 PIANO ASSETTO IDROGEOLOGICO P.A.I. ZONE DI ATTENZIONE GEOLOGICA !< !< Perimetrazione e classi di pericolosità geologica QUADRO CONOSCITIVO COMPLEMENTARE AL P.A.I. P1 - Pericolosità geologica moderata Banca dati I.F.F.I. - P2 - Pericolosità geologica media Inventario dei fenomeni franosi in Italia 0302350700 0302!<350700 P3 - Pericolosità geologica elevata !< Localizzazione dissesto franoso non delimitato P4 - Pericolosità geologica molto -

DRIOL MAURIZIO Curriculum Vitae 2018.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome MAURIZIO DRIOL Data di Nascita 15/07/1958 Qualifica Dirigente Scolastico Amministrazione Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca - Istituzione scolastica : BASILIANO - SEDEGLIANO (UDIC819005) Incarico attuale Tipo incarico : Effettivo, dal 01/09/2018 al 31/08/2021 presso la sede :null ,dal :null al :null - Istituzione scolastica : MAJANO E FORGARIA (UDIC81500T) Tipo incarico : Reggenza, dal 01/09/2018 al 31/08/2019 Utilizzo/Comando presso la sede :null ,dal :null al :null Numero telefonico 0432916028 dell'ufficio Fax dell'ufficio 0432916028 E-mail istituzionale [email protected] Posta elettronica certificata [email protected] Altri Recapiti TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE - Diploma universitario Titoli di Studio E1: DIPLOMA UN. ABILITAZIONE VIGILANZA NELLE SCUOLE ELEMENTARI conseguito il null con la votazione di null/null Altri titoli di studio e professionali Incarichi ricoperti : Esperienze professionali - Istituzione scolastica : SAN DANIELE DEL FRIULI (UDIC85200R) (incarichi ricoperti) Tipo incarico : Reggenza, dal 01/08/2018 al 31/08/2018 - Istituzione scolastica : MAJANO E FORGARIA (UDIC81500T) Tipo incarico : Reggenza, dal 01/09/2017 al 31/08/2018 - Istituzione scolastica : BASILIANO - SEDEGLIANO (UDIC819005) Tipo incarico : Effettivo, dal 01/09/2015 al 31/08/2018 - Istituzione scolastica : SAN DANIELE DEL FRIULI (UDIC85200R) Tipo incarico : Reggenza, dal 13/06/2018 al 30/07/2018 Pag. 1 di 3 02/11/2018 13.12.36 - Istituzione