Reforming Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Elections Have Consequences

LIBERTYVOLUME 10 | ISSUE 1 | March 2021 WATCHPOLITICS.LIVE. BUSINESS. THINK. BELIBERTY. FREE. ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES BETTER DAYS AHEAD George Harris CENSORSHIP & THE CANCEL CULTURE Joe Morabito JUST SAY “NO” TO HARRY REID AIRPORT Chuck Muth REPORT: SISOLAK’S EMERGENCY POWERS LACK LEGAL AUTHORITY Deanna Forbush DEMOCRATS WANT A 'RETURN TO CIVILITY'; WHEN DID THEY PRACTICE IT? Larry Elder THE LEFT WANTS UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER, NOT UNITY Stephen Moore THE WORLD’S LARGEST CANNABIS SUPERSTORE COMPLEX INCLUDES RESTAURANT + MORE! Keep out of reach of children. For use only by adults 21 years of age and older. LIBERTY WATCH Magazine The Gold Standard of Conservatism. Serving Nevada for 15 years, protecting Liberty for a lifetime. LIBERTYWATCHMagazine.com PUBLISHER George E. Harris [email protected] EDITOR content Novell Richards 8 JUST THE FACTS George Harris ASSOCIATE EDITORS BETTER DAYS AHEAD Doug French [email protected] 10 FEATURE Joe Morabito Mark Warden CENSORSHIP & THE CANCEL CULTURE [email protected] 11 MILLENNIALS Ben Shapiro CARTOONIST GET READY FOR 4 YEARS Gary Varvel OF MEDIA SYCOPHANCY OFFICE MANAGER 12 MONEY MATTERS Doug French Franchesca Sanchez SILVER SQUEEZE: DESIGNERS IS THAT ALL THERE IS? Willee Wied Alejandro Sanchez 14 MUTH'S TRUTHS Chuck Muth JUST SAY “NO” TO HARRY REID AIRPORT CONTRIBUTING WRITERS John Fund 18 COVER Doug French ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES Thomas Mitchell Robert Fellner 24 COUNTERPUNCH Victor Davis Hanson Nicole Maroe Judge Andrew P. Napolitano 26 LEGAL BRIEF Deanna Forbush Ben -

Investor Presentation

BROADCASTING DIGITAL INVESTOR PUBLISHING PRESENTATIONINVESTOR PRESENTATION NASDAQ: SALM | December 2019 Safe Harbor Certain statements in this presentation constitute “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the private securities litigation reform act of 1995. Such forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance or achievements of the company to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such “forward-looking statements.” This presentation also contains “non-GAAP financial measures” within the meaning of regulation G, specifically station operating income and Adjusted EBITDA. In conformity with regulation G, information reconciling the non-GAAP financial measures included in this presentation to the most directly comparable financial measures prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles is available on the investor relations portion of the company's website at www.Salemmedia.com, as part of the most current report on form 8-K and earnings release issued by Salem Media Group. 1 Who We Are Salem Media Group is America’s leading multimedia company specializing in Christian and conservative content 99 Radio Stations Salem’s history dates back to 1974 with the launch of our first Christian Teaching and Talk radio station, and went public in 1999 BROADCASTING We reach millions of Christians and conservatives daily across the nation with compelling content, -

Mr. Jackson's Opus from D.C. to Hollywood Arbitron: Radio Ratings Game Teen DI Spins Ho-*- a GREAT MORNING SHOW IS HARD to FIND

VOL. II Na. 6 LOS ANGELES COUNTY'S ONLY RADIO MAGAZINE1 996 Mr. Jackson's Opus From D.C. to Hollywood Arbitron: Radio Ratings Game Teen DI Spins Ho-*- A GREAT MORNING SHOW IS HARD TO FIND Acerbic Funny Topical Adults Only 5 am - 10 am KLAC 570 AM STEREO 1<,1U;uOiut:Ic VI Ilic Contents November/December 1996 Talk Radio Maestro Listings Talk 22 News 23 Rock 24 Adult Standards 25 Classical 25 Public 26 Jazz 29 Oldies 29 From his early years grow- Features ing up amidst the terrors COVER STORY: Michael Jackson . .13 of wartime England, Arbitron: Radio Ratings Game Michael Jackson dreamed Counting radioheads 19 of Hollywood's sunshine Young DJ Plays Big Band and glamour. Now an 14 -year -old starts show on KORG . .21 American celebrity in his own right, married to the daughter of a movie star, Jackson is a seasoned interviewer Depts. with his own star on the Hollywood SOUNDING OFF 4Walk of Fame. For the last 30 years, he RADIO ROUNDUP 6has taken the measure of the world's RATINGS 20greatest personalities, from Whitehall LOONEY POINT OF VIEW 30to the White House, making them accessible to his legion of loyal talk radio fans on KABC 790 AM. Los Angeles Radio GuidePublishers Ben Jacoby and Shireen Alafi P.O. Box 3680 Editor in Chief Shireen Alafi Santa Monica CA. 90408Editorial Coordinator/Photographer Sandy Wells Voice: (310) 828-7530Photographer/Production Ben Jacoby Fax (310) 828-0526Contributing Writers . .. Kathy Gronau, Thom Looney, Subscriptions: 512 Lynn Walford, John Cooper e-mail: [email protected] Associate Communi-Graphics www.radioguide.comGeneral Consultant Ira Jeffrey Rosen © 1996 by Allay Publishing. -

Salem Corporate Guide (PDF)

America’s leading media company serving the nation’s Christian and conservative communities. 1 From a single radio station to America’s predominant multi-media enterprise serving the values-driven audience Launch of Salem purchases FAMILYTALK Hot Air Salem partners with CNN in moderating on XM Satellite Twitchy Salem Communications the presidential debates and serves as the exclusive radio broadcaster Acquisition of eight stations Red State becomes Christian Teaching & Talk Expansion into the in major markets from Salem Media Group platform grows News/Talk format Clear Channel 1975 -1993 1995 1997 2000 2010 - 2014 2015 2016 1974 1993 1999 2002 2006 2010 - 2012 2014 2015 TODAY KDAR Salem launches Salem Communications Acquisition of Acquisition of Acquisition of Acquisition of Acquisition of five Salem’s digital, multi-media enterprise OXNARD, CA Salem Radio Network (SRN), makes its initial BibleStudyTools.com Xulon Press GodTube Regnery Publishing, radio stations from is the undisputed leader in its space: one of the top full-service public oering on Crosswalk.com Townhall.com WorshipHouse Media America’s leading Radio Disney networks in the U.S. NASDAQ: SALM conservative publisher Radio Stations in the top markets Launch of Salem Books, across the United States Salem Web Network (SWN) our Christian book Acquisitions of radio stations launches with a single website imprint 3,000-plus Salem Radio Network (SRN) Aliates including those in: New York, and now is home to some Los Angeles and Chicago of the most well-known More than 100 million -

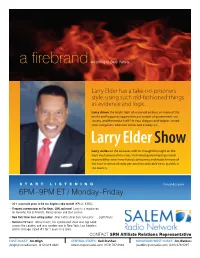

Larry Elder Show Larry Sizzles on the Airwaves with His Thoughtful Insight on the Day’S Most Provocative Issues

a firebrand according to Daily Variety. Larry Elder has a take-no-prisoners style, using such old-fashioned things as evidence and logic. Larry shines the bright light of reasoned analysis on many of the myths and hypocrisy apparent in our system of government, our society, and the media itself. He slays dragons and topples sacred cows using facts, common sense, and a ready wit. Larry Elder Show Larry sizzles on the airwaves with his thoughtful insight on the day’s most provocative issues. His limited government/personal responsibility views have fueled controversy and made him one of the most in-demand radio personalities and cable news pundits in the country. START LISTENING larryelder.com 6PM–9PM ET / Monday–Friday • 20+ successful years in the Los Angeles radio market (KRLA, KABC) • Frequent commentator on Fox News, CNN and more! Larry is a regular on on Hannity, Fox & Friends, Nancy Grace and Don Lemon. • New York Times best-selling author: Dear Father, Dear Son: Two Lives . Eight Hours • National TV host: Moral Court, his syndicated show was top rated across the country and was number one in New York, Los Angeles, and in Chicago (rated #1 for 7 years in a row). CONTACT SRN Affiliate Relations Representative EAST COAST: Jim Bligh CENTRAL STATES: Kelli DeShan MOUNTAIN/WEST COAST: Jim Watkins [email protected] (212) 419.4663 [email protected] (972) 707.6882 [email protected] (239) 470.9297 LARRY ELDER AFFILIATE CLOCK 58:50 00:00 Local 55:00 NEWS or 1:00 Program Local 6:00 06:00 Show Open Content 5 52:00 Network 1:00 Local 2:00 Program Program Content 4 Content 1 44:00 Network 2:00 Local 2:00 17:00 Network 2:00 Local 2:00 40:00 Program Content 3 Program 21:00 Content 2 Local 4:00 34:00 30:00 6PM–9PM ET Weekdays on Salem Radio Network Westwood One Technical Services Satellite Info (914) 908-3210 Satellite / AMC-18 Westwood One XDS Cue for Local Liners LarryElder Show XDS Netcue T09 for station liners Salem Technical Operations (972) 367-1934 Cue for Local Breaks XDS Netcue T08 for local breaks Live Daily Program 6PM–9PM EST. -

Larry Elder Nominated for the Radio Hall of Fame

July 13, 2020 Larry Elder Nominated for the Radio Hall of Fame CAMARILLO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Salem Media Group, Inc. (NASDAQ: SALM) announced today that Salem Radio Network’s host Larry Elder has officially been nominated for induction into the Radio Hall of Fame for 2020. There are 24 nominees in six categories. Larry was nominated in the category of Active Network Syndication, along with three other national hosts. Larry’s program airs weekdays 3pm to 6pm PT on over 350 affiliates across the country. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200713005524/en/ “Larry has proven to be one of the true super stars in talk radio. Listeners love his take-no-prisoners attitude,” said Salem Senior VP of Spoken Word, Phil Boyce. “Larry is a consummate pro, a true entertainer, and packs a ton of information into every show. He is very deserving of this honor.” Larry’s nomination will be voted on by over 600 radio professionals across the country, and the winner will be announced in August. “This is truly an honor Larry Elder (Photo: Business Wire) to be considered for this award,” said Larry Elder. “I am grateful to have this platform, and hopefully I can make a difference for good in America. We have a country to save.” Larry’s program was heard for years on KABC in Los Angeles before he moved over to AM 870 The Answer in LA. He was given the syndicated slot in April of 2016 by the Salem Radio Network. -

Listener Guide

KGDC 1320- M/92.9-FM, KGDC2 102.3-FM Listener Guide Format: The format for both KGDC and KGDC2 is News, Talk, Sports, Culture Target Area: Walla Walla (WA), Benton (WA), Franklin (WA) and Umatilla (OR) counties Demographics: Adults age 25 – 64 (primary); 35+ core Home owners, high income, college educated, stocks/securities owners Our Mission: To redeem our culture by providing a relevant radio listening experience. We strive not just to entertain our listeners, but to engage, inform, and inspire them to be active and generous citizens who make a difference in the lives of their families, their friends, their associates and their community. Market Exclusives: Fox News Radio (12 mins/hour), Townhall.com News Radio (12 mins/hour), Seattle Mariners, WSU Cougars, Gonzaga Bulldogs, Walla Walla High School Blue Devils, College Place High School Hawks, DeSales Catholic High School Fighting Irish, and all features and talk shows described herein. Daily Features: Break Point Eric Metaxas / John Stonestreet Cal Thomas Commentary Cal Thomas Dennis Miller Minute Dennis Miller Earth Date University of Texas Family Talk Dr. James Dobson Focus on the Family Minute Focus on the Family Fox Business Report Neil Cavuto, Maria Bartiromo Fox News Commentary Guy Benson, Chris Wallace, others GK Chesterton Minute Dale Ahlquist Horse Show Minute Rick Lamb Life Issues Brad Mattes Living Well Pam Smith Lou Dobbs Financial Report Lou Dobbs Phyllis Schlafly Report Eagle Forum Pro-Life Perspective National Right to Life Star Date University of Texas McDonald Observatory The foundational pieces in fulfilling our mission are market exclusives for both of the top sources of conservative news. -

KGDC 1320-AM/92.9-FM, KGDC2 102.3-FM Listener Guide

KGDC 1320-AM/92.9-FM, KGDC 2 102.3-FM Listener Guide Format: News, Talk, Sports, Culture Target Area: Walla Walla (WA) and Umatilla (OR) counties Demographics: Adults age 25 – 64 (primary); 35+ core Home owners, high income, college educated, stocks/securities owners Our Mission: To redeem our culture by providing a relevant radio listening experience. We strive not just to entertain our listeners, but to engage , inform , and inspire them to be active and generous citizens who make a difference in the lives of their families, their friends, their associates and their community. Market Exclusives: Fox News, Townhall.com News, Seattle Mariners, WSU Cougars, Walla Walla High School Blue Devils Athletics, College Place High School Hawks Athletics, DeSales High School Fighting Irish Athletics, and all talk shows described herein. Daily Features: Break Point Eric Metaxas Cal Thomas Commentary Cal Thomas Dennis Miller Minute Dennis Miller Family Money Minute Sami Cone Family Talk Dr. James Dobson Focus on the Family Minute Focus on the Family Fox Business Report Neil Cavuto GK Chesterton Minute Dale Ahlquist Horse Show Minute Rick Lamb Life Issues Brad Mattes Living Well Pam Smith Phyllis Schlafly Report Phyllis Schlafly Pro-Life Update National Right to Life Star Date University of Texas McDonald Observatory The foundational piece in fulfilling our mission is our market exclusive for top-and-bottom-of-the-hour Fox News , which all major polls (including Quinnipiac University, Public Policy Polling, Brookings, the Public Religion Research Institute) say is the most trusted name in the news world across the United States. We also have a market exclusive on Townhall.com News . -

Download .Pdf

The ENTERTAINMENT AGE Fall 2015 • MEETLaw Quadrangle THE NEW VICTORS The new first-year class at Michigan Law is made up of 267 students chosen from a pool of 4,368 applicants. The class is tied for highest GPA in the School’s history and has the second-highest LSAT average score. Racial and ethnic minorities make up 24 percent of the class, while LGBT students comprise 7.5 percent. It is a group with widely varying backgrounds: ice carver, Olympic-caliber runner, FBI investigative specialist, an electrician who co-founded a Haitian solar cell company. Their culinary backgrounds are impressive: One was a pastry kitchen assistant at Zingerman’s Bakehouse; another wrote a thesis on the chemistry of baked chocolate desserts; and a third worked at an Italian winery. They represented a variety of media organizations: The New York Times, The New Yorker, Al Jazeera. The air controller from Camp Pendleton may be in some classes with2 the pilot combat trainer from the U.S. Air Force or the intelligence analyst from the Air National Guard. And the class is 50 percent male, 50 percent female. CALL PHOTOGRAPHY 05 A MESSAGE FROM DEAN WEST 06 BRIEFS 08 Townie-in-Chief 10 FEATURES 30 @UMICHLAW 30 Curriculum Changes Better Serve Student Needs 31 New Veterans Legal Clinic Will Serve Those Who Serve Us 32 A Landmark Supreme Court Term 42 GIVING 54 CLASS NOTES 54 Elder, ’77: ‘Confronting Bias’ 56 Zhang, LLM ’85: Facilitating Business Deals with Cultural Insights 60 Bakst, ’97: Advocating for Work/Family Balance 68 CLOSING 22 INDEPENDENTS’ DAY 2 FEATURES COUNSEL FOR THE BROADWAY INBOUND KARDASHIANS AND OUTBOUND 12 26 WORDS HAVE MEANING A FISH STORY 32 63 3 [ OPENING ] 5 Quotes You’ll See… …In This Issue of the Law Quadrangle 1. -

PBS BW Seminar Book FA.Indd

THE FUTURE OF PUBLIC TELEVISION 2004 Arts and Humanities in Public Life Conference December 2–3, 2004 Executive Summary Cultural Policy Center The Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies The University of Chicago Copyright © 2005 The University of Chicago, Cultural Policy Center For more information or for copies of this book contact: Cultural Policy Center at The University of Chicago The Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies 1155 East 60th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60637–2745 ISBN: 0–9747407–1–7 Phone: 773–702–4407 Fax: 773–702–0926 Email: [email protected] http://culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu Photography: Lloyd De Grane 2004. Design: Froeter Design Company, Inc. Printed in the United States. Housed at the Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies, the Cultural Policy Center at The University of Chicago fosters research to inform public dialogue about the practical workings of culture in our lives. “The Future of Public Television” was the fifth in a series of “Arts in Humanities and Public Life” conferences held by the Cultural Policy Center. The conference was produced with the generous support of the Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies, the McCormick Tribune Foundation, the Irving Harris Foundation, and Jamee Rosa. Complete conference transcripts available at: http://culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu. CONFERENCE DEDICATION The 2004 Arts and Humanities in Public Life Conference was dedicated to the memory of Irving B. Harris (1910– 2004), whose notable success as a businessman played a distant second to his remarkable philanthropy for children’s welfare, public policy, and the arts. -

KGDC 1320-AM/92.9-FM, KGDC2 102.3-FM Listener Guide

KGDC 1320-AM/92.9-FM, KGDC2 102.3-FM Listener Guide Format: The format for both KGDC and KGDC2 is News, Talk, Sports, Culture Target Area: Walla Walla (WA), Benton (WA), Franklin (WA) and Umatilla (OR) counties Demographics: Adults age 25 – 64 (primary); 35+ core Home owners, high income, college educated, stocks/securities owners Our Mission: To redeem our culture by providing a relevant radio listening experience. We strive not just to entertain our listeners, but to engage, inform, and inspire them to be active and generous citizens who make a difference in the lives of their families, their friends, their associates and their community. Market Exclusives: Fox News Radio (12 mins/hour), Townhall.com News Radio (12 mins/hour), Seattle Mariners, WSU Cougars, Walla Walla High School Blue Devils Athletics, College Place High School Hawks Athletics, DeSales Catholic High School Fighting Irish Athletics, and all features and talk shows described herein. Daily Features: Break Point Eric Metaxas / John Stonestreet Cal Thomas Commentary Cal Thomas Dennis Miller Minute Dennis Miller Earth Date University of Texas Family Talk Dr. James Dobson Focus on the Family Minute Focus on the Family Fox Business Report Neil Cavuto, Maria Bartiromo Fox News Commentary Guy Benson, Chris Wallace, others GK Chesterton Minute Dale Ahlquist Horse Show Minute Rick Lamb Life Issues Brad Mattes Living Well Pam Smith Lou Dobbs Financial Report Lou Dobbs Phyllis Schlafly Report Eagle Forum Pro-Life Perspective National Right to Life Star Date University of Texas McDonald Observatory The foundational pieces in fulfilling our mission are market exclusives for both of the top sources of conservative news.