The Music Icidemy the Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Mylapore Times Epaper

MYLAPORE TIMES YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD NEWSPAPER Vol. 25, No. 43 May 8 - 14, 2021 8 pages Free Circulation OFFICE : 2498 2244, 2467 1122 EDITORIAL : 2466 0269 WEBSITE : www.mylaporetimes.com 2 MYLAPORE TIMES May 8 - 14, 2021 USEFUL CONTACTS TRIBUTES Here is a check list of some people who provide food V. Dinakaran, former physi- Kartik Fine Arts for many years and Hailing for those affected by the virus. Some do it for the cal education teacher, P. S. Snr. headed a few other cultural bodies from Ray- Sec. School, like Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan; during ampettai, a patients, some also provide for the family of the affected, Mylapore his tenure he actively took part in village near if they are unable to cook – passed away events at Mylapore sabha halls.’ Thiruvaiyaru on 14th He headed many a corporate (Thanjavur April. He firm and the Chennai Super Kings district), she ● Thaligai in Luz ( opp. Nageswara Rao Park) says its was 56. management. migrated to diet is prescribed by the well-known Ayurvedic doctor Alumni Madras in Dr. PLT Girija. It follows the ‘pathiyam’ cooking process. It Venkatesh Enuga Seetharama Reddy, the seventies with her husband, offers a package for 7 days or 14 days three times a day. (1999 batch) president of Telugu Mahajana Sa- Jagannathan, a manager at Punjab Pick up or delivery to doorstep also done through Swiggy / mentions that ‘master’ personally majam and of National Bank. Dunzo. intervened with his parents when Sri Venugopal Mythili was among the earliest he was in class XII to ensure he Vidyalaya settlers in Second Main Road, Contact - 6374-071618 – call Nalina. -

The Significance of Fire Offering in Hindu Society

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU THE SIGNIFICANCESOCIETY OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU SOCIETY S. Sushrutha H. R. Nagendra Swami Vivekananda Yoga Swami Vivekananda Yoga University University Bangalore, India Bangalore, India R. G. Bhat Swami Vivekananda Yoga University Bangalore, India Introduction Vedas demonstrate three domains of living for betterment of process and they include karma (action), dhyana (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). As long as individuality continues as human being, actions will follow and it will eventually lead to knowledge. According to the Dhatupatha the word yajna derives from yaj* in Sanskrit language that broadly means, [a] worship of GODs (natural forces), [b] synchronisation between various domains of creation and [c] charity.1 The concept of God differs from religion to religion. The ancient Hindu scriptures conceptualises Natural forces as GOD or Devatas (deva that which enlightens [div = light]). Commonly in all ancient civilizations the worship of Natural forces as GODs was prevalent. Therefore any form of manifested (Sun, fire and so on) and or unmanifested (Prana, Manas and so on) form of energy is considered as GOD even in Hindu tradition. Worship conceives the idea of requite to the sources of energy forms from where the energy is drawn for the use of all 260 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 life forms. Worshiping the Gods (Upasana) can be in the form of worship of manifest forms, prostration, collection of ingredients or devotees for worship, invocation, study and discourse and meditation. -

The Science Behind Sandhya Vandanam

|| 1 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 Sri Vaidya Veeraraghavan – Nacchiyar Thirukkolam - Thiruevvul 2 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 �ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || Sri Nrisimha Priya ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ AN AU T H O R I S E D PU B L I C A T I O N OF SR I AH O B I L A M A T H A M H. H. 45th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham H.H. 46th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham Founder Sri Nrisimhapriya (E) H.H. Sri Lakshminrisimha H.H. Srivan Sathakopa Divya Paduka Sevaka Srivan Sathakopa Sri Ranganatha Yatindra Mahadesikan Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikan Ahobile Garudasaila madhye The English edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya not only krpavasat kalpita sannidhanam / brings to its readers the wisdom of Vaishnavite Lakshmya samalingita vama bhagam tenets every month, but also serves as a link LakshmiNrsimham Saranam prapadye // between Sri Matham and its disciples. We confer Narayana yatindrasya krpaya'ngilaraginam / our benediction upon Sri Nrisimhapriya (English) Sukhabodhaya tattvanam patrikeyam prakasyate // for achieving a spectacular increase in readership SriNrsimhapriya hyesha pratigeham sada vaset / and for its readers to acquire spiritual wisdom Pathithranam ca lokanam karotu Nrharirhitam // and enlightenment. It would give us pleasure to see all devotees patronize this spiritual journal by The English Monthly Edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya is becoming subscribers. being published for the benefit of those who are better placed to understand the Vedantic truths through the medium of English. May this magazine have a glorious growth and shine in the homes of the countless devotees of Lord Sri Lakshmi Nrisimha! May the Lord shower His benign blessings on all those who read it! 3 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 4 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || CONTENTS Sri Nrisimha Priya Owner: Panchanga Sangraham 6 H.H. -

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

DIVYA VANI Volume 2 Number 4 10Th April 1963

DIVYA VANI Volume 2 Number 4 10th April 1963 A periodical Publication of the “Meher Vihar Trust” An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook June 2018 All words of Meher Baba copyright 2018 Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust Ahmednagar, India Source and short publication history: Divya Vani = Divine voice. Quaterly, v.1, no. 1 (July 1961), v. 3. no. 2 (Oct. 1963): bimonthly, v. 1. no. 1 (Jan. 1964), v. 2 no. 3 (May 1965): monthly. v. 1. no. 1l (July 1965), v. 12, no. 6 (June 1976): bimonthly, v. 1. no. 1 (Aug. 1976), v.14. no. 1 (Jan. 1978): quarterly, v. 1, no. 1 (Jan. 1979), Kakinada : Avatar Meher Baba Mission. 1961- v. : ill.. ports. Subtitle: An English monthly devoted to Avatar Meher Baba & His work (varies). Issues for July - Oct. 1961 in English or Telugu. Editor: Swami Satya Prakash Udaseen. Place of publication varies. Publisher varies: S. P. Udaseen (1961-1965): S.P. Udaseen on behalf of the Meher Vihar Trust (1965-1969): Meher Vihar Trust (l970-Apr. 1974). Ceased publication? eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust's eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust's web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba's lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

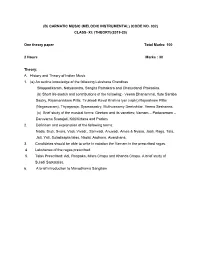

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

Book Only Cd Ou160053>

TEXT PROBLEM WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY CD OU160053> Vedant series. Book No. 9. English aeries (I) \\ A hand book of Sri Madhwacfaar^a's POORNA-BRAHMA PH I LOSOPHY by Alur Venkat Rao, B.A.LL,B. DHARWAR. Dt. DHARWAR. (BOM) Publishers : NAYA-JEEYAN GRANTHA-BHANDAR, SADHANKERI, DHARWAR. ( S.Rly ) Price : Superior : 7 Rs. 111954 Ordinary: 6 Rs. (No postage} Publishers: Nu-va-Jeevan Granth Bhandar Dharwar, (Bombay) Printer : Sri, S. N. Kurdi, Sri Saraswati Printing Press, Dharwar. ,-}// rights reserved by the author. To Poorna-Brahma Dasa; Sri Sri : Sri Madhwacharya ( Courtesy 1 he title of my book is rather misleading for though the main theme of the book is Madhwa philosophy, it incidentally and comparitively deals with other philosophies such as that of Sri Shankara Sri Ramanuja and Sri Mahaveer etc. So, it is use- ful for all those who are interested in such subjects. Sri Madhawacharya, the foremost Vaishnawa philosopher, who is the last of the three great Teachers,- Sri Shankara, Sri Ramanuja and Sri Madhwa,- is so far practically unknown to the English-reading public of India. This is, therefore the first attempt to present his philosophy to the wider public. Madhwa philosophy has got two aspects, one universal and the other, particular. I have tried to place before the readers both these aspects. I have re-assessed the values of Madhwa and other philosophies, and have tried to find out also the greatest common factor,-an angle of vision which has not been systematically adopted by any body. He is a great Harmoniser. In fact mine isS quite a new approach, I have tried to put old things in a new way. -

Divya Dvaita Drishti

Divya Dvaita Drishti PREETOSTU KRISHNA PR ABHUH Volume 1, Issue 4 November 2016 Madhva Drishti The super soul (God) and the individual soul (jeevatma) reside in the Special Days of interest same body. But they are inherently of different nature. Diametrically OCT 27 DWADASH - opposite nature. The individual soul has attachment over the body AKASHA DEEPA The God, in spite of residing in the same body along with the soul has no attach- OCT 28 TRAYODASHI JALA POORANA ment whatsoever with the body. But he causes the individual soul to develop at- tachment by virtue of his karmas - Madhvacharya OCT 29 NARAKA CHATURDASHI OCT 30 DEEPAVALI tamasOmA jyOtirgamaya OCT 31 BALI PUJA We find many happy celebrations in this period of confluence of ashwija and kartika months. NOV 11 KARTIKA EKA- The festival of lights dipavali includes a series of celebrations for a week or more - Govatsa DASHI Dvadashi, Dhana Trayodashi, Taila abhyanjana, Naraka Chaturdashi, Lakshmi Puja on NOV 12 UTTHANA Amavasya, Bali Pratipada, Yama Dvititya and Bhagini Tritiya. All these are thoroughly en- DWADASHI - TULASI joyed by us. Different parts of the country celebrate these days in one way or another. The PUJA main events are the killing of Narakasura by Sri Krishna along with Satyabhama, restraining of Bali & Lakshmi Puja on amavasya. Cleaning the home with broom at night is prohibited on other days, but on amavasya it is mandatory to do so before Lakshmi Puja. and is called alakshmi nissarana. Next comes completion of chaturmasa and tulasi puja. We should try to develop a sense of looking for the glory of Lord during all these festivities.