Multilingual Policies and Practices of Universities in Three Bilingual Regions in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad De Zaragoza

Universidad de Zaragoza www.unizar.es © Universidad de Zaragoza Texts: Gabinete de Rector Design: San Jimes Estudio www.sanjimes.com Translation: Trasluz S.L. Print: Servicio de Publicaciones. Universidad de Zaragoza. Jaca FRANCE The University of Huesca Zaragoza is a public Burdeos 469km teaching and research institution whose aim is to serve society. As the Zaragoza largest higher education Toulouse 397km centre in the Ebro Valley, Pau 235km the University combines La Almunia de almost fi ve centuries Doña Godina País Vasco of tradition and history 276km (since 1542) with a constantly updated José Antonio Mayoral Murillo. University of range of courses. Its 312km Zaragoza Rector Barcelona main mission is to generate and convey Teruel Zaragoza knowledge to provide Madrid students with a broad 315km education. The University bases its principles on quality, solidarity and Valencia openness and aims to be SPAIN 308km an instrument of social transformation to drive Paraninfo Building. Faculties of Medicine and University Statue of our Nobel Prize, economic and cultural Sciences (year 1940). Currently, the seat of the Santiago Ramón y Cajal development. Rectorate Campuses 2 - - 3 Arts and Humanities Faculty of Medicine (Zaragoza) s Medicine Faculty of Arts (Zaragoza) Faculty of Education (Zaragoza) University Technological College ’ Engineering and Classical Studies Faculty of Veterinary Science Pre-school Teacher Architecture (La Almunia) (affiliated) English Studies (Zaragoza) Primary School Teacher Civil Engineering Hispanic Philology Veterinary -

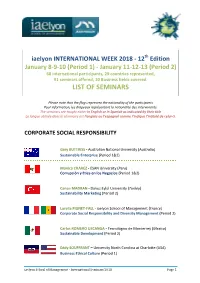

List of Seminars

iaelyon INTERNATIONAL WEEK 2018 - 12 th Edition January 8-9-10 (Period 1) - January 11-12-13 (Period 2) 68 international participants, 29 countries represented, 91 seminars offered, 10 Business fields covered. LIST OF SEMINARS Please note that the flags represent the nationality of the participants Pour information, les drapeaux représentent la nationalité des intervenants. The seminars are taught either in English or in Spanish as indicated by their title La langue utilisée dans le séminaire est l’anglais ou l’espagnol comme l’indique l’intitulé de celui-ci . CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Gary BUTTRISS - Australian National University (Australia ) Sustainable Enterprise (Period 1&2) Monica CHAVEZ - ESAN University (Peru) Corrupción y Etica en los Negocios (Period 1&2) Canan MADRAN - Dokuz Eylül University (Turkey ) Sustainability Marketing (Period 2) Lorella PIGNET-FALL - iaelyon School of Management (France ) Corporate Social Responsibility and Diversity Management (Period 2) Carlos ROMERO USCANGA - Tecnológico de Monterrey (Mexico ) Sustainable Development (Period 2) Eddy SOUFFRANT – University North Carolina at Charlotte (USA ) Business Ethical Culture (Period 1) iaelyon School of Management - International Seminars 2018 Page 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP Olli KUIVALAINEN - Lappeenranta University of Technology (Finland) Internationalization of SMEs and International Entrepreneurship (Period 2) Renato PEREIRA - ISCTE Business School (Portugal) Business Modelling and Planning (Period 2) Alejandro ZUNIGA FONSECA - Universidad Iberoamericana -

University of Lleida (ES) – Summary

Continuing Education at the University of Lleida (ES) – Summary 1. History The university was created in 1300 by the king Jaume II with the idea to increase Catalonia’s power in the Mediterranean area. Students from other parts of Spain went to Lleida and the commerce and manufacture (paper and books in particular) increased considerably. Lleida became a center of exchange and diffusion of ideas and scientific innovation. Wars with other countries and internal issues put the university in a period of decline. The Spanish reform created a new model of university and in 1717 a new university was formed in Cervera which implied the closing down of the University of Lleida as such. In 1991 the Catalan Parliament approved the opening of the University of Lleida again. Lleida is the most important city in the interior of Catalonia with 120000 inhabitants and about 10000 students. The university has 5 campuses. 2. Continuing Education at the University of Lleida The Statutes of the university establish the improvement of teaching and the contribution to lifelong learning in order to develop social cohesion, equality of opportunities and quality of life. One of the university’s objectives is the development of continuing education programmes under very strict quality parameters. Continuing education is understood as all those courses that have as main objective to upgrade knowledge in any form as well as the development of personal and professional competences. The main characteristic of the continuing education at the university is its thematic diversity, that implies a complementary education in the basic education of Bachelor degree and it has been thought in a global way for those interested to improve their professional and cultural qualifications. -

The University of Lleida Has Its Roots in the Estudi General De Lleida

The University of Lleida has its roots in the Estudi General de Lleida, which was created in 1300 by virtue of a charter granted to the city of Lleida by King Jaume II of Aragon. He based his decision on a papal bull issued in Rome on 1st April 1297, by Pope Boniface VIII. With the birth of the Estudi General, a university neighbourhood grew up in Lleida with students arriving from all over the Kingdom of Aragon and many other regions. As happens nowadays, this breathed new life into the city. However, the students and professors formed a community with special privileges and immunities. The parish church of Saint Martin became established as the university’s venue for solemn ceremonies, and it received financial backing from the municipality and the Cathedral Chapter. Despite the flourishing times that the University of Lleida experienced until the first half of the 16th century, its situation became more complicated with growing competition from the new universities that were being created in other territories in the kingdom. The schools of the Estudi General de Lleida managed to maintain the prestige they had acquired over time despite the Estudi having lost the exclusivity and hegemony bestowed on it through its privileged foundation charter. From the second half of the 17th century, a period of decadence began that would continue until the reign of Philip V in the 18th century. After the War of the Spanish Succession, the Bourbon reformers decided to create a new university model in Catalonia. The small town of Cervera, some 70 kilometres east of Lleida was chosen as the location for a new university to thank the town for its support to Philip V, who Lleida and Barcelona had opposed from the outset of the war. -

The University and the Region: an Historical Overview and Some Reflections on the Case of Catalonia

CONEIXEMENT I SOCIETAT 04 ARTICLES THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA Ricard Pié* The increase in the number of publicly funded universities in Catalonia, the emergence of four private universi- ties, the major urban impact on the cities of Girona, Lleida, Reus, Tarragona and Vic as a result of the implantation of their respective universities, together with demographic factors such as the decline in the higher education population, as well as the need to rationalise the present map of universities in Catalonia, call for a considered appraisal of the relationship between the university and the region, as well as the relevance of that relationship to regional and academic restructuring policies affecting Catalan universities in the future. Contents 1. The university and its surrounding region 2. The founding of the medieval university, an urban phenomenon 3. The crisis of the traditional university model and the re-founding of the university as a temple of knowledge 4. The American experience: from rural college to mass university 5. The university as a motor of regional development 6. Spanish universities and their struggle for renewal 7. The difficult years, from the Spanish Civil War to the coming of democracy 8. The explosion of the university map in Spain under the new autonomous regions 9. The genesis of today’s university map in Catalonia 10. Some questions concerning the Catalan university map in relation to the differential value of region * Ricard PIÉ is an architect and senior lecturer at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia 16 THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTÒRICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA 1. -

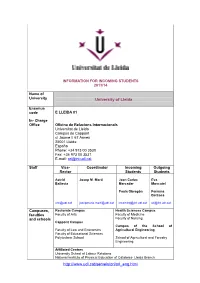

University of Lleida

INFORMATION FOR INCOMING STUDENTS 2013/14 Name of University University of Lleida Erasmus code E LLEIDA 01 In- Charge Office Oficina de Relacions Internacionals Universitat de Lleida Campus de Cappont c/ Jaume II 67 Annex 25001 Lleida España Phone: +34 973 00 3530 Fax: +34 973 00 3531 E-mail: [email protected] Staff Vice- Coordinator Incoming Outgoing Rector Students Students Astrid Josep M. Martí Joan Carles Eva Ballesta Mercader Moscatel Paula Obregón Fermina Berzosa [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Campuses, Rectorate Campus Health Sciences Campus faculties Faculty of Arts Faculty of Medicine and schools Faculty of Nursing Cappont Campus Campus of the School of Faculty of Law and Economics Agricultural Engineering Faculty of Educational Sciences Polytechnic School School of Agricultural and Forestry Engineering Affiliated Centres University School of Labour Relations National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia- Lleida Branch http://www.udl.cat/serveis/ori/ori_eng.html ACADEMIC INFORMATION Academic You can check the academic offer of the University of Lleida in the following offer link http://www.udl.cat/en/studies/studies_all.html Academic You can check the academic offer in English of the University of Lleida in the offer in following link English http://www.etsea.udl.cat/en/mobility/Subject_En.html Academic First semester 2013-14 Calendar Welcome activities: from 28/08/13 to 10/09/13 Christmas break from 21/12/13 to 06/01/14 Lessons and exams: from 16/09/13 to 07/02/14 Second semester 2013-14 Welcome activities: (provisional): from 27/01/14 to 07/02/14 Easter break: from 22/03/14 to 31/03/14 Lessons and exams: from 10/02/14 to 27/06/14 Optional exams period: Optional 1st and 2nd terms exams: from 30/06/14 to 11/07/14 Teaching The teaching languages in the University of Lleida are Catalan, Spanish and languages English. -

Erasmus Fact Sheet

INFORMATION FOR INCOMING STUDENTS 2020/21 Universitat de Lleida Name University of Lleida Erasmus code E LLEIDA 01 International Relations Universitat de Lleida Phone: Campus de Cappont +34 973 003534 / +34 973 702773 Office in charge of Jaume II, 67 bis incoming students E-25001 Lleida (Catalonia) E-mail: [email protected] Spain Vice- Rector Montserrat Gea [email protected] Erasmus Institutional Coordinator International Relations Coordinator Josep M. Martí [email protected] Contact person for bilateral agreements Juan Carlos Mercader Staff [email protected] Incoming students & Paula Obregón Fermina Berzosa & Cristina Domínguez (Erasmus exchanges) [email protected] Outgoing students Eva Moscatel (other exchange programmes) Rectorate Campus -Faculty of Humanities Health Sciences Campus -Faculty of Medicine Cappont Campus -Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy Campuses, -Faculty of Law, Economics and faculties Tourism ETSEA Campus and schools -Faculty of Education, -School of Agrifood and Forest Engineering Psychology and Social Work - Polytechnic School Affiliated Centres -National Institute of Physical Education (INEFC Lleida) -Ostelea School of Tourism and Hospitality (Barcelona) -School of Labour Relations Information for Erasmus incoming students: http://www.udl.cat/ca/serveis/ori/estudiantat_estranger/eng/erassms/ ACADEMIC INFORMATION Academic contacts: http://www.udl.cat/ca/serveis/ori/eng/#directory Departmental Coordinators http://www.udl.cat/ca/en/studies/ Bachelor’s degree programmes: http://www.udl.cat/ca/en/studies/studies_bycentres/ Study Programmes Master’s degree programmes: http://www.udl.cat/ca/en/studies/poficials_eng/ PhD degree programmes: http://www.doctorat.udl.cat/en/programes/propis/ Courses in English http://www.udl.es/serveis/ori/estudiantat_estranger/eng/infoeng/subjects.html Academic Calendar http://www.udl.cat/ca/serveis/ori/estudiantat_estranger/eng/infoeng/academic/ The linguistic policy regulation of the University of Lleida establishes that Catalan, Spanish and English are the three working languages at the University of Lleida. -

Information for International Students 2019/2020 Table of Content

Information for International Students 2019/2020 Table of Content MASARYK UNIVERSITY ...................................................................................................................2 THE FACULTY OF LAW – PAST AND PRESENT .................................................................2 DEGREE PROGRAMMES ...............................................................................................................3 Bachelor .....................................................................................................................................3 Public Administration Legal Specializations ............................................................................................3 Master .........................................................................................................................................3 Law and Legal Science ........................................................................................3 Public Administration ............................................................................................3 Doctoral ......................................................................................................................................4 Theoretical Legal Sciences ...............................................................................4 Comparative Constitutional Law .....................................................................4 Comparative Corporate, Foundation and Trust Law ............................4 Legal Theory and Public Affairs .......................................................................4 -

Regulations Governing Doctoral Courses at the University of Lleida

REGULATIONS GOVERNING DOCTORAL COURSES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LLEIDA Article 1. Definition and objectives 1.1. The doctoral courses of the University of Lleida (UdL) are aimed at training students to become high-quality researchers who are able to join national and international research teams in the public and private sectors. 1.2. The doctoral studies at the UdL are structured as doctoral programmes. Each doctoral programme includes taught courses and research activities that lead to the awarding of the doctoral degree by the UdL. 1.3. The doctoral studies are governed by the provisions of Royal Decree 1393/2007, of 29 October (Spanish Official State Gazette of 30 October), by the present regulations and by any complementary regulations that may be established. Article 2. The doctoral programmes 2.1. Each doctoral programme is the organised set of all taught courses and research activities that lead to the awarding of the doctoral degree by the UdL. 2.2. The taught courses and research activities of each doctoral programme are divided into a taught period and a research period that students must pass in order to obtain the doctorate. 2.3. The coordinator of the doctorate of each postgraduate program will propose the general objectives and admission criteria of the doctoral programme to the vice-rector's office responsible for third-cycle studies. These criteria must ensure the viability of the proposal in accordance with the guidelines laid down by the Doctoral Studies Sub-Committee: a) General objectives of the programme b) Lines of research of the programme d) Administrative processes (periods and procedure for pre-registration and registration) and telephone numbers and e-mail addresses of the coordinator and the administrative services of the programme. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Student Guide 2008-10

A two-year double degree Master’s Programme ACADEMIC STUDY GUIDE 2016–2018 University of Eastern Finland AgroParisTech, France University of Lleida, Spain University of Freiburg, Germany University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria MSc EF Study Guide 2016-2018: Version 3 May 2016 Copyright: MSc European Forestry secretariat All photographs have been provided by the students and staff of MSc European Forestry partner universities. The consortium reserves the right to revise modules and amend regulations and procedures at any time. 2 FOREWORD ___________________________ Welcome to our MSc European Forestry programme! MSc European Forestry is a unique, multicultural master’s degree programme in Europe. It aims at providing you an insight to the various practices, administrative characteristics and state-of-the-art technologies of the contemporary forest cluster. Forestry is a multidisciplinary field of science where MSc European Forestry programme takes you to an exciting journey throughout Europe. It highlights the importance of urban forestry, introduces you to the applications of multiple-use of forests, and teaches you the practices in mountain forestry as well as in technologies used in production oriented forest industry. The variety of subjects within European Forestry allows you to choose the selection of studies that best suit your ambitions. Throughout the studies, our professional teaching personnel are committed to support your learning process towards a scientific way of thinking. I am proud to act on behalf of our consortium of universities that jointly provide the best knowledge in European Forestry today! On the behalf of all the partners, I congratulate you and wish you all the best for your two-year studies! Professor Timo Tokola, Coordinator of the MSc European Forestry programme 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ___________________________ ERASMUS MUNDUS AND EUROPEAN UNION ...................................................................... -

The University of Barcelona in Figures

The University of Barcelona in figures October 2015 The University of Barcelona, founded in the tion of the Arab-Euro Conference on High- year 1450, has a demonstrably dynamic, criti- er Education (AECHE), and the creation of cal, constructive and humanist character strategic alliances with partners including that places it alongside the leading centres the University of Montpellier and the Com- of education, science and critical thought in plutense University of Madrid, consolidate Spain and the world. institutional policies on research, teaching quality, knowledge transfer and internation- This prestige is reflected in the size of the alization. The combination of these factors student community, which numbers around has enabled the UB to maintain its position 65,000, and in the demand for places, which among the highest-placed Spanish universi- regularly exceeds availability. As a general- ties in major international rankings. ist university, the UB offers quality teach- ing across each of the principal branches The figures presented here summarize the of knowledge: humanities, health sciences, UB’s actions and activities over the last aca- social sciences, experimental sciences and demic year in the areas of teaching, research, engineering. In the academic year 2014- innovation, internationalization and mobility. 2015, students were distributed across 67 bachelor’s degrees, 141 university master’s degrees, 48 doctoral programmes, over 700 postgraduate courses and some 400 on-site and distance lifelong learning courses, in ad- dition to a selection of massive open online courses, or MOOCs. In the area of research, the UB has opened its new Humanities and Social Science Park and coordinates the Spanish node of EIT Health, the European Institute of Knowledge and Dídac Ramírez Technology’s knowledge and innovation Rector community (KIC) for healthy living and ac- tive ageing, which aims to strengthen the work of the HUBc health sciences campus.