Dialogue Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shri Dorjee Khandu Hon’Ble Chief Minister Arunachal Pradesh

SPEECH OF SHRI DORJEE KHANDU HON’BLE CHIEF MINISTER ARUNACHAL PRADESH AT THE 54TH NDC MEETING AT VIGYAN BHAVAN New Delhi December 19, 2007 54TH NDC MEETING SPEECH OF SHRI DORJEE KHANDU HON’BLE CHIEF MINISTER ARUNACHAL PRADESH 2 Hon’ble Prime Minister and the Chairman of NDC, Hon’ble Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission, Hon’ble Union Ministers, My colleague Chief Ministers, Distinguished members of the Planning Commission, Senior Officers, Ladies and Gentlemen. It is indeed a proud privilege and honour for me to participate in this 54th NDC meeting. This meeting has been convened essentially to consider and approve the Draft 11th Five Year Plan (2007-2012). The visionary and comprehensive Eleventh Five Year Plan envisions to steer the process of development through rapid reduction of poverty and creation of employment opportunities, access to essential services like health and education specially for the poor, equality of opportunity, empowerment through education and skill development to meet the objectives of inclusiveness and sustainability . However, I would like to share our views on some of the important issues and recommendations highlighted in the agenda. 2) Let me start with reiterating what our Hon’ble Prime Minister has stated in his Independence Day address on 15th August 2005. “ in this new phase of development, we are acutely aware that all regions of the country should develop at the same pace. It is unacceptable for us to see any region of the country left behind other regions in this quest for development. In every scheme of the Government, we will be making all efforts to ensure that backward regions are adequately taken care of. -

Download Full Report

P�R�E�F�A�C�E� 1.� This�Report�has�been�prepared�for�submission�to�the� Governor under Article 151 of the Constitution.� 2.� Chapters�I�and�II�of�this�Report�respectively�contain�Audit� observations�on�matters�arising�from�examination�of� Finance�Accounts�and�Appropriation�Accounts�of�the�State� Government for the year ended 31 March 2010.� 3.� Chapter�III�on�‘Financial�Reporting’�provides�an�overview� and�status�of�the�State�Government’s�compliance�with� various�financial�rules,�procedures�and�directives�during� the current year.� 4.� Audit�observations�on�matter�arising�from�performance� audit�and�audit�of�transactions�in�various�departments� including�the�Public�Works�department,�audit�of�stores�and� stock,�audit�of�autonomous�bodies,�Statutory�Corporations,� Boards�and�Government�Companies�and�audit�of�revenue� receipts for the year ended 31 March 2010 are included in a� separate Report.� 5.� The�audit�has�been�conducted�in�conformity�with�the� Auditing�Standards�issued�by�the�Comptroller�and�Auditor� General of India. CHAPTER I Finances of the State Government Pr o f i l e of th e St a t e Area-wise, AR U N A C H A L PR A D E S H , which became a full-fledged state on February 20, 1987, is the largest state in the north-eastern region. Till 1972, it was known as the North- East Frontier Agency (NEFA). It gained the Union Territory status on January 20, 1972 and was renamed as Arunachal Pradesh. The State, being one of the Special Category State, is dependent on central assistance for plan investment because of poor resource base. -

Kibithoo Can Be Configured As an Entrepôt in Indo- China Border Trade

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Kibithoo Can Be Configured as an Entrepôt in Indo- China Border Trade JAJATI K PATTNAIK Jajati K. Pattnaik ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor, at the Department of Political Science, Indira Gandhi Government College, Tezu (Lohit District), Arunachal Pradesh Vol. 54, Issue No. 5, 02 Feb, 2019 Borders are the gateway to growth and development in the trajectory of contemporary economic diplomacy. They provide a new mode of interaction which entails de-territorialised economic cooperation and free trade architecture, thereby making the spatial domain of territory secondary in the global economic relations. Taking a cue from this, both India and China looked ahead to revive their old trade routes in order to restore cross-border ties traversing beyond their political boundaries. Borders are the gateway to growth and development in the trajectory of contemporary economic diplomacy. They provide a new mode of interaction which entails de-territorialised economic cooperation and free trade architecture, thereby making the spatial domain of territory secondary in the global economic relations. Taking a cue from this, both India and China looked ahead to revive their old trade routes in order to restore cross-border ties traversing beyond their political boundaries. The reopening of the Nathula trade route in 2016 was realised as a catalyst in generating trust and confidence between India and China. Subsequently, the success of Nathula propelled the academia, policymakers and the civil society to rethink the model in the perspective of Arunachal Pradesh as well. So, the question that automatically arises here is: Should we apply this cross-border model in building up any entrepôt in Arunachal Pradesh? The response is positive and corroborated by my field interactions at the ground level. -

6 the SLBC Had Discussed in Details the Strategy for Coverage Of

Agenda – 1 Adoption of minutes : The minutes of State Level Bankers’ Committee meetings held on 29.06.2011 was circulated to all members. In this connection, a letter for amendment has been received from Reserve Bank of India , Guwahati, (for opening of bank branches in 4 centres covering 6 blocks) as under : The SLBC had discussed in details the strategy for coverage of unbanked blocks in Arunachal Pradesh and extensive mapping of these blocks to existing branches, new branches,BCs etc, was carried out in the meeting . While efforts taken by the SLBC to meet the target of coverage of unbanked blocks by March’2012, is much appreciated, it may be pointed out that a one time exercise had already been carried out to identify centres, i.e. ‘ Agreed List’ of centres , to be included under RBI Subvention scheme and the scheme applies only to the 12 centres drawn up for the state of Arunachal Pradesh, viz. Mariyang, Gensi, Riga, Pongchao, Wakka, Pakke Kessang , Taliha, Rumgong, Chiyangtazo, Khimyang , Yupia and Mechuka . The house may discuss on the issue. Since no other request for amendment has been received, the house may adopt the other aspects of the said minutes. Agenda – 2 Follow up action on the decisions of the SLBC meeting dated 29.06.2011 (last meeting) No. Action to be taken Action by Action taken 1. SLBC Meeting to be All Banks/ SLBC Members Advised all the members invariably be participated accordingly. by all decision making authorities 2. Govt of Arunachal Pradesh Concerned departments, Govt departmemts may to discourage keeping their Govt of A.P. -

Rainfall Distribution and Weather Activity: 26.08.2021 to 01.09.2021

Govt. of India / भारत सरकार Ministry of Earth Sciences / पृ镍वी ववज्ञान मंत्रालय India Meteorological Department / भारत मौसम ववज्ञान ववभाग Regional Meteorological Centre /क्षेत्रीय मौसम कᴂद्र Guwahati – 781 015/ गुवाहाटी - ७८१०१५ Weekly Weather Report for Arunachal Pradesh, Assam& Meghalaya, Nagaland- Manipur-Mizoram & Tripura for week ending on 29.09.2021 Synoptic Feature: “Monsoon Trough” persisted and passed through Jaisalmer, Chittorgarh,Tikamgarh, Sidhi, Ambikapur, Jharsuguda,Puri and thence SE-wards to EC-Bay of Bengal on 23rd.It persisted and passed through Jaisalmer,Ajmer,Nowgong,Daltonganj,Jamshedpur,Digha and thence SE-wards to EC-Bay of Bengal on 24th.It persisted and passed through Jaisalmer, Kota, Mandla, Sambhalpur, Paradeep and thence ESE –wards to the centre of Deep Depression over NW & adjoining WC-Bay of Bengal on 25th.It persisted and passed through Bikaner,Kota,Sagar,Pendra Road,Jharsuguda and thence ESE-wards to the centre of Cyclonic Storm “Gulab” over Northwest & adjoining WC-Bay of Bengal on 26th.It persisted and passed through Jaisalmer,Udaipur,Akola,Chandrapur,centre of Deep depression over south Odisha & adjoining south Chattisgarh,Vishakapatnam and thence ESE- wards to EC-Bay of Bengal on 27th.The monsoon Trough at mean sea level has become disorganized on 28th. The Deep Depression over north and adjoining central Bay of Bengal moved westwards with a speed of 14 kmph in last 6 hours and lay centred at 0830 hrs IST of 25th September,over northwest and adjoining WC_Bay of Bengal near Lat.18.4°N and Long 89.3°E, about 470 km ESE of Gopalpur(Odisha) & 540 km ENE of Kalingapatnam(Andhra Pradesh).It is likely to intensify in to a Cyclonic Storm during next 06 hours. -

Arunachal Pradesh Information Commission, Itanagar

ARUNACHAL PRADESH INFORMATION COMMISSION, ITANAGAR ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 1 The real Swaraj will come not by the acquisition of authority by a few, but by the acquisition of capacity by all to resist authority when abused. - MAHATMA GANDHI “Laws are not masters but servants, and he rules them who obey them”. -HENRY WARD BEECHER “Democracy requires an informed citizenry and transparency of information which are vital to its functioning and also to contain corruption and to hold Government and their instrumentalities accountable to the governed” ( Preamble, RTI Act 2005 ) 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT This 11th & 12th Annual Reports of Arunachal Pradesh Information Commission 2016 - 2017 has been prepared in one volume. The data for preparation of this report are collected from Government Departments of the State. According to Information provided by the departments, the total number of Public Authorities in the State is 30 and the number of Public Information Officers is more than 310. The Right to Information Act, 2005 is a landmark legislation that has transformed the relationship between the citizen and the State. This legislation has been created for every citizen, to hold the instrumentalities of Governance accountable on a day to day basis. The legislation perceives the common man as an active participant in the process of nation building by conferring on him a right to participate in the process through the implementation of the Right to Information Act. It is more than a decade Since the RTI Act has been in operation in the State. The State Information Officers and Appellate Authorities are quasi judicial functionaries under the RTI Act with distinctive powers and duties and they constitute the cutting edge of this “Practical regime of information”, as envisaged in the preamble of the Right to Information Act. -

Government of Arunachal Pradesh Planning Department Itanagar

GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH PLANNING DEPARTMENT ITANAGAR No. PD(UF)-1/2008 Dated, Itanagar, the 3rd January, 2009. To 1) The Deputy Commissioner, Tawang/Bomdila/Seppa/Koloriang/Yupia/ziro/Pasighat/Aalo/Daporijo/ Yingkiong/Anini/Roing/Hawai/Tezu/Changlang/Khonsa Arunachal Pradesh 2) The Additional Deputy Commissioner, Singchung/Sagalee/Mechuka/Basar/Rumgong/Tuting/Hayuliang/Namsai/ Miao/Jairampur/Longding Arunachal Pradesh Subject:- Allocation of funds under UNTIED FUND for the year 2008-09. Sir/Madam, I am to convey the Govt. approval for placement of Rs.430.00 lakh under “Untied Fund” for 2008-09 at the rate of Rs. 20.00 lakh per Deputy Commissioner and Rs.10.00 lakh per Additional Deputy Commissioner (with independent charges) at the disposal of respective Deputy Commissioners / Additional Deputy Commissioners (as per list given below). 2. The expenditure should be booked under Major Head “3451”-Secretairat Economic Services-Sub Major Head-00-Minor Head-102-District Planning Machinery-Sub-Head – 04 – Untied Fund – Detailed Head-(01-DC, Aalo), (02-DC, Tezu), (03-DC, Ziro), (04-DC, Bomdila), (05-DC, Khonsa), (06-DC, Pasighat), (07-DC, Anini), (08-DC, Daporijo), (09-DC, Seppa), (10-DC, Tawang), (11-DC, Changlang), (12-DC, Yupia), (13-DC, Yingkiong), (14-DC, Koloriang), (15-DC, Roing), (16-DC, Anjaw), (18-ADC, Namsai), (19-ADC, Longding), (20- ADC, Miao), (21-ADC, Basar), (22-ADC, Rumgong), (23-ADC, Jairampur), (24-ADC, Mechuka), (25-ADC, Hayuliang) – Object Head-50 – Other charges – Code No.02 (Plan) Demand No.6. The District-wise allocation under Untied Fund for the year 2008-09 is given below. -

Arunachal Pradesh

Census of India 2011 ARUNACHAL PRADESH PART XII-B SERIES-13 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK ANJAW VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ARUNACHAL PRADESH ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT ANJAW H KILOMETRES 5 0 5 10 15 I I K Ta C T a m l l B a o p n R R . N . D u E r I t e t n Kala o n R g R. N. * K a zo Go M m K iyu hu u u o C Ch m r Th i T an D A e M N a c . h i . CHAGLAGAM D i R la e D KIBITHOO i I T o achi . r M a a R r u K a a H I N D Thu D shi I A R. S METENGLIANG Se Ti GOILIANG Y t a rei R. p B ak Ti WALONG J R a T n g S N h . N e - t n HAYULIANG u T T d i a u D m a G n u R d n T i T id T i d i i . n N g i R. U I A T h a H R S c - a li a e c C a Chik m u MANCHAL T h H i b T i L T oh l i i a t or i T m ellu T R . T Kam i i P u n T u n . g R la Ti L g HAWAI M n a w O o g Ti T an ith a K R. -

Annual Operating Plan 2009-10 Outlay and Expenditure of Centrally Sponsored Schemes Including Fully Funded by Govt

GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH ANNUAL OPERATING PLAN 2009 - 10 INDEX SL.NO CONTENTS PAGE-NO. 1 Basic features i - v 2 Abstract of Outlay and Expenditure 1 - 2 3 Outlay and Expinditure on Direction and Administration under Plan 3 4 Specific schemes with various components 4 5 District wise break up of Outlay 5 6 Physical Targets and Achievement 6 7 District wise break up of Physical targets and Achievement 7 8 Achievement of tenth Plan and Targets for Annual plan 2009-10 8 9 Statement of staff strength of the Department 9 - 10 10 Statement on proposal for New Posts 11 - 12 11 Expenditure and Outlays for salaries and wages 13 12 Statement on Vehicles 14 13 Details of on going scheme 15-35 14 Proposal for new schemes / services 36-70 15 Outlay & Expenditure of loan linked schemes 71-74 16 Earmarked schemes by Planning Commissioning 75-78 17 Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Financial) 79-83 18 Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Physical) 84-89 19 Furnishing information relaeted NEC, NLCPR scheme 90-92 20 On-going incomplete Projects funded under PM's Package 93-97 21 Details of Assets 98-99 GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH DEPARTMENT OF POWER ANNUAL OPERATING PLAN FOR 2009 – 10 BASIC FEATURES The Plan Outlay of the Department of Power as allocated by State Planning Department for the financial year 2009-10 is Rs 5000.00 lakh (Rupees Five Thousand Lakh ) only including the earmarked schemes. The projected minimum resource requirement of the Department of Power for 2009-10 is Rs.37079.04 (Rupees Thirty Seven Thousand Seventy Nine Lakh and Four Thousand) only. -

Contact Details of Ros and Aros

Telephone Nos of R.Os and AROs Sl No. and Name Returning Officer Assistant Returning Officer No of A/Cs. Name Phone Nos AROs Phone Nos 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. 1-Lumla (ST) DC Shri Gamli Padu, DC 1. ADC, Lumla ADC ,Tawang Tawang 03794-222221(O) 2. C.O , Dudunghar 3794-264213(O) 222222® 3. C.O Zemithang 264202® 222259(Fax) 9436676390(M) 2 2-Tawang 9436051027 1. ADC, Tawang EAC,Tawang (ST) 2. EAC , Tawang 03794-223254(o) 3. C.O , Kitpi 224105® 9436051288(M) 3 3-Mukto ADC, Jang Shri Duly Kamduk, 1. EAC, Jang CO,Mukto (ST) ADC 2. C.O , Mukto 03794-244770(O) 03794-255588(O) 3. C.O , Thingbu 244710® 254815® 9436250325 254814 (Fax) 9402062203 4 4-Dirang(ST) DC, Bomd Smti. Swati Sharma, 1. ADC, Dirang ADC,Dirang ila DC 2. C.O , Thembang 03780-242221(O) 03782-222021(O) 242226® 222087(Election) 9436895184(M) 222022® CO, Thembang 222100(Fax) 03780-242793 (O) 9436634001(M) 9436837221 (M) 5 5- 1. SDO, Rupa SDO,Rupa Kalaktang(ST) 2. EAC, Kalaktang 03782-232287(O) 232288® 232362(Election) 9436221187 Kalaktang 03782-266405(O) 266430® 9436837571(M) 6. 6-Thrizino- 1.ADC,Singchun ADC, Singchung Buragaon(ST) 2. ADC, Thrizino 03782-273313(O) 3. EAC,B/Pung 273388® 273464(Election) 9436837571(M) ADC,Thrizino 9436068587(M) EAC,Bhalukpung 03782-234424(O) 234423® 7. 7-Bomdila(ST) 1.SDO (Hq), Bdl 03782-222087(O) 222701® 9436837726(M) 2.EAC,(Hq), Bdl 9436057232 8. 8-Bameng (ST) DC, Seppa Shri Pige Ligu, DC 1. EAC, Bameng 03787-222363 03787- 9436054305 222576/222412(O) 2. -

Annual Operating Plan 2008-09 Outlay and Expenditure of Centrally Sponsored Schemes Including Fully Funded by Govt

GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH NO.CE(P)/EEZ/SP&C/AOP/08-09/4697-720 Dated 03/03/2009 ANNUAL OPERATING PLAN 2008 - 09 INDEX SL.NO CONTENTS PAGE-NO. 1 Basic features i - vi 2 Abstract of Outlay and Expenditure 1 - 2 3 Outlay and Expinditure on Direction and Administration under Plan 3 4 Specific schemes with various components 4 5 District wise break up of Outlay 5 6 Physical Targets and Achievement 6 7 District wise break up of Physical targets and Achievement 7 8 Achievement of tenth Plan and Targets for Annual plan 2008-09 8 9 Statement of staff strength of the Department 9 - 10 10 Statement on proposal for New Posts 11 - 18 11 Expenditure and Outlays for salaries and wages 19 12 Statement on Vehicles 20 13 Details of on going scheme 21-40 14 Proposal for new schemes / services 41-77 15 Outlay & Expenditure of loan linked schemes 78 - 81 16 Earmarked schemes by Planning Commissioning 82 - 85 17 Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Financial) 86 - 89 18 Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Physical) 90 - 95 19 Furnishing information relaeted NEC, NLCPR scheme 96 - 98 20 On-going incomplete Projects funded under PM's Package 99 - 103 21 Details of Assets and allocation under Maintenance 104-105 CE(P), EEZ, DoP, ITANAGAR GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH DEPARTMENT OF POWER ANNUAL OPERATING PLAN FOR 2008 – 09 BASIC FEATURES The Plan Outlay of the Department of Power for financial year 2008 - 09 allocated by State Planning Department is Rs 12019.49 lakh (Rupees Twelve thousand Nineteen hundred lakh Forty Nine thousand) against the minimum requirement of Rs. -

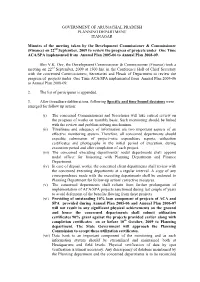

Minutes of Review the Progress of Projects Under One Time ACA/SPA

GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH PLANNING DEPARTMENT ITANAGAR Minutes of the meeting taken by the Development Commissioner & Commissioner (Finance) on 22nd September, 2009 to review the progress of projects under One Time ACA/SPA implemented from Annual Plan 2005-06 to Annual Plan 2008-09. Shri V.K. Dev, the Development Commissioner & Commissioner (Finance) took a meeting on 22nd September, 2009 at 1500 hrs. in the Conference Hall of Chief Secretary with the concerned Commissioners, Secretaries and Heads of Department to review the progress of projects under One Time ACA/SPA implemented from Annual Plan 2005-06 to Annual Plan 2008-09. 2. The list of participates is appended. 3. After threadbare deliberations, following Specific and time bound decisions were emerged for follow up action: (i) The concerned Commissioners and Secretaries will take critical review on the progress of works on monthly basis. Such monitoring should be linked with the review and problem solving mechanism. (ii) Timeliness and adequacy of information are two important aspects of an effective monitoring system. Therefore, all concerned departments should expedite submission of project-wise expenditure reports, utilization certificates and photographs in the initial period of execution, during execution period and after completion of each project. (iii) The concerned executing departments/ nodal departments shall appoint nodal officer for liaisoning with Planning Department and Finance Department. (iv) In case of deposit works, the concerned client departments shall review with the concerned executing departments at a regular interval. A copy of any correspondence made with the executing departments shall be endorsed to Planning Department for follow-up action/ corrective measures.