Thesis May Be Reproduced, Distributed, Stored in a Retrieval System, Or Transmitted in Any Form Or by Any Means, Without Prior Written Permission of the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disclosure Summary for CME Learners ATS 2017 International Conference - Washington D.C

American Thoracic Society - Disclosure Summary for CME Learners ATS 2017 International Conference - Washington D.C. - May 19-24, 2017 1) RELEVANT COMMERCIAL INTERESTS DISCLOSED BY CME PLANNERS AND PRESENTERS Initial Report as of May 15, 2017 Use Adobe PDF "Find" option to search for specific name. Presenter disclosures may continue on a successive page, or begin on a preceding page. Agrawal, Rishi Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Boehringer Ingelheim b.v. Speaker Agusti, Alvar Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Almirall Research Support Speaker Advisory Committee Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP Speaker Advisory Committee Research Support Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Boehringer Ingelheim b.v. Advisory Committee Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest GlaxoSmithKline, LLC. Advisory Committee Research Support Speaker Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Speaker Advisory Committee Research Support Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Novartis Pharma AG Speaker Advisory Committee Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation Advisory Committee Research Support Speaker 1 of 106 Agusti, Alvar Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Menarini Speaker Research Support Akulian, Jason A. Name of Commercial Interest and Type(s) of Relationship with that Commercial Interest Veran Medical Technologies, Inc. -

Geslaagdenkrant 2016 2 HET BELANG VAN LIMBURG

wij zijn geslaagd! geslaagdenKRanT 2016 2 HET BELANG VAN LIMBURG aerts, Beringen. Handelswetenschappen en bedrijfskunde: Hogere ZeevaartscHool onderscheiding: ester swennen, genk. antwerpen Master in de Audiovisuele Kunsten Bachelor in het bedrijfsmanagement voldoende wijze: marieke stulens, Bilzen. onderscheiding: vladimir stonis, sint-truiden. Nautische Wetenschappen: onderscheiding: nele vandael, genk. voldoening: Hamza mouatassim, genk. Master in de Nautische Wetenschappen Onderwijs: onderscheiding: Jonathan vandenbossche, lommel. luca scHool oF arts Bachelor in het onderwijs: secundair onderwijs voldoening: marcella schetz, opitter. MA beeldende kunsten (Genk): erasmusHogescHool Sociaal-agogisch werk: Afstudeerrichting Fotografie Brussel met onderscheiding: Boumediene Belbachir, genk. Bachelor in de gezinswetenschappen op voldoende wijze: Jonas camps, Hechtel. onderscheiding: anne-martje Beckers, lummen; Kristel Management, Media & Maatschappij: cuyvers, Beringen; sara De Becker, Heers; nadine MA productdesign (Genk): Bachelor in het Communicatiemanagement Hermans, Dilsen-stokkem; an van lishout, Heusden- voldoende wijze: nele couwberghs, tessenderlo; Zolder; Dagmar vandebroek, Koersel. Afstudeerrichting Fotografie voldoening: marleen Bovie, tongeren; christine lavrey- maximiljaan van der Beken, Zonhoven. Katrijn caelen, genk. onderscheiding: mathijs vanduffel, overpelt. sen, Hasselt; valerie monnens, Heusden-Zolder; sandra Afstudeerrichting Communicatie- en Multime- vossen, Bocholt. Bachelor in het Hotelmanagement diadesign Bachelor -

Juilliard Dance

Juilliard Dance Senior Graduation Concert 2019 Welcome to Juilliard Dance Senior Graduation Concert 2019 Tonight, you will experience the culmination of a transformative four-year journey for the senior class of Juilliard Dance. Through rigorous physical training and artistic and intellectual exploration, all of the fourth-year dancers have expanded the possibilities of their movement abilities, stretching beyond what they thought possible when entering the program as freshmen. They have accepted the challenge of what it means to be a generous citizen artist and hold that responsibility close to their hearts. Chosen by the dancers, the solos and duets presented tonight have been commissioned for this evening or acquired from existing repertory and staged for this singular occasion. The works represent the manifestation of an evolution of growth and the discovery of their powerfully unique artistic voices. I am immensely proud of each and every fourth-year artist; it has been a joy and an honor to get to know the senior class, a group of individuals who will inevitably change the landscape of the field of dance as it exists today. Please join me for a standing ovation, cheering on the members of the class of 2019 as they take the stage for the last time together in the Peter Jay Sharp Theater. Well done, dancers—we thank you for your beautiful contributions to our Juilliard community and to the world beyond our campus. Sincerely, Little mortal jump Alicia Graf Mack Director, Juilliard Dance Cover: Alejandro Cerrudo's This page: Collaboration -

2018 Abstract Book

CONTENTS Table of Contents INFORMATION Continuing Medical Education .................................................................................................5 Guidelines for Speakers ..........................................................................................................6 Guidelines for Poster Presentations .........................................................................................8 SPEAKER ABSTRACTS Abstracts ...............................................................................................................................9 POSTER ABSTRACTS Basic Research (Location – Room 101) ...............................................................................63 Clinical (Location – Room 8) ..............................................................................................141 2018 Joint Global Neurofibromatosis Conference · Paris, France · November 2-6, 2018 | 3 4 | 2018 Joint Global Neurofibromatosis Conference · Paris, France · November 2-6, 2018 EACCME European Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education 2018 Joint Global Neurofibromatosis Conference Paris, France, 02/11/2018–06/11/2018 has been accredited by the European Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (EACCME®) for a maximum of 27 European CME credits (ECMEC®s). Each medical specialist should claim only those credits that he/she actually spent in the educational activity. The EACCME® is an institution of the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS), www.uems.net. Through an agreement between -

CONTENTS Journal VOLUME 42 / NUMBER 6 / DECEMBER 2013

EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY CONTENTS journal VOLUME 42 / NUMBER 6 / DECEMBER 2013 EDITORIALS 1433 The European Lung Corner Jean-Paul Sculier 1435 Putting noninvasive lung mechanics into context Peter M.A. Calverley and Ramon Farre 1438 The CFTR and EGFR relationship in airway vascular growth, and its importance in cystic fibrosis Jay A. Nadel 1441 Bronchodilator combinations for COPD: real hopes or a new Pandora’s box? Nicolas Roche and Pascal Chanez 1446 Clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a framework for moving forward David J. Lederer 1449 Therapeutic drug management: is it the future of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment? Shashikant Srivastava, Charles A. Peloquin, Giovanni Sotgiu and Giovanni Battista Migliori 1454 Legionnaires’ disease in Europe: all quiet on the eastern front? Julien Beauté, Emmanuel Robesyn and Birgitta de Jong, on behalf of the European Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance Network 1459 Avoiding overdiagnosis in lung cancer screening: the volume doubling time strategy Marie-Pierre Revel 1464 Does drug-induced emphysema exist? Norbert F. Voelkel, Shiro Mizuno and Masanori Yasuo European lung corner 1469 Canaries in the coal mine Maeve Barry ORIGINAL ARTICLES COPD 1472 The impact of COPD on health status: findings from the BOLD study Open Christer Janson, Guy Marks, Sonia Buist, Louisa Gnatiuc, Thorarinn Gislason, Mary Ann McBurnie, ERJ Rune Nielsen, Michael Studnicka, Brett Toelle, Bryndis Benediktsdottir and Peter Burney 1484 Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy: the -

Intersection Between Mental Health and the Juvenile Justice System Mental Health Disorders Are Prevalent Among Youths in the Juvenile Justice System

Last updated: July 2017 www.ojjdp.gov/mpg Intersection between Mental Health and the Juvenile Justice System Mental health disorders are prevalent among youths in the juvenile justice system. A meta-analysis by Vincent and colleagues (2008) suggested that at some juvenile justice contact points, as many as 70 percent of youths have a diagnosable mental health problem. This is consistent with other studies that point to the overrepresentation of youths with mental/behavioral health disorders within the juvenile justice system (Shufelt and Cocozza 2006; Meservey and Skowyra 2015; Teplin et al. 2015). However, prevalence varies depending on the stage in the justice system at which youths are assessed. In a nationwide study, the prevalence of diagnosed disorders increased the further that youths were processed in the juvenile justice system (Wasserman et al. 2010). While there appears to be a prevalence of youths with mental health issues in the juvenile justice system, the relationship between mental health problems and involvement in the system is complicated, and it can be hard to disentangle correlational from causal relationships between the two (Shubert and Mulvey 2014). This literature review will focus on the scope of mental health problems of at-risk and justice-involved youths; the impact of mental health on justice involvement as well as the impact of justice involvement on mental health; disparities in mental health treatment in the juvenile justice system; and evidence- based programs that have been shown to improve outcomes for youths with mental health issues. Defining Mental Health and Identifying Mental Health Needs Defining Mental Health. According to the U.S. -

Croi 2021 Program Committee

General Information CONTENTS WELCOME . 2 General Information General Information OVERVIEW . 2 CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION . 3 CONFERENCE SUPPORT . 4 VIRTUAL PLATFORM . 5 ON-DEMAND CONTENT AND WEBCASTS . 5 CONFERENCE SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE . 6 PRECONFERENCE SESSIONS . 9 LIVE PLENARY, ORAL, AND INTERACTIVE SESSIONS, AND ON-DEMAND SYMPOSIA BY DAY . 11 SCIENCE SPOTLIGHTS™ . 47 SCIENCE SPOTLIGHT™ SESSIONS BY CATEGORY . 109 CROI FOUNDATION . 112 IAS–USA . 112 CROI 2021 PROGRAM COMMITTEE . 113 Scientific Program Committee . 113 Community Liaison Subcommittee . 113 Former Members . 113 EXTERNAL REVIEWERS . .114 SCHOLARSHIP AWARDEES . 114 AFFILIATED OR PROXIMATE ACTIVITIES . 114 EMBARGO POLICIES AND SOCIAL MEDIA . 115 CONFERENCE ETIQUETTE . 115 ABSTRACT PROCESS Scientific Categories . 116 Abstract Content . 117 Presenter Responsibilities . 117 Abstract Review Process . 117 Statistics for Abstracts . 117 Abstracts Related to SARS-CoV-2 and Special Study Populations . 117. INDEX OF SPECIAL STUDY POPULATIONS . 118 INDEX OF PRESENTING AUTHORS . .122 . Version 9 .0 | Last Update on March 8, 2021 Printed in the United States of America . © Copyright 2021 CROI Foundation/IAS–USA . All rights reserved . ISBN #978-1-7320053-4-1 vCROI 2021 1 General Information WELCOME TO vCROI 2021 Welcome to vCROI 2021! The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world for all of us in so many ways . Over the past year, we have had to put some of our HIV research on hold, learned to do our research in different ways using different tools, to communicate with each other in virtual formats, and to apply the many lessons in HIV research, care, and community advocacy to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic . Scientists and community stakeholders who have long been engaged in the endeavor to end the epidemic of HIV have pivoted to support and inform the unprecedented progress made in battle against SARS-CoV-2 . -

Click Here to Access Copyright Information

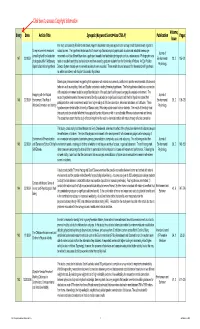

Volume, Entry Date Article Title Synopsis (Keyword Search=Use CTRL-F) Publication Pages Issue In a study conducted by Rita Berto and others, Kaplan's fascination study was applied to the concept of soft facination with regards to Do eye movements measured natural scenes. The hypothesis tested was that if shown high fascination photographs such as urban and industrial scenes, eye Journal of across high and low fascination movement would be different than when a participant viewed a low fascination photograph such as a nature scene. Photographs were 147 2/2/2009 Environmental 28, 2 185-191 photographs differ? Addressing rated on a scale from high to low fascination and then viewed by graduate students from the University of Padova. An Eye Position Psychology Kaplan's fascination hypothesis Detector System tracked eye movements and results were recorded. These results showed a support for the researcher's hypothesis as well as consistency with Kaplan's fascination hypothesis. Based upon previous research suggesting that experience with natural environments contributes to positive environmental attitudes and behaviors such as recycling, Hinds and Sparks conducted a testing three key hypotheses. The first hypothesis stated that a connection with a natural environment would be a significant indicator of the participant's willingness to engage in a natural environment. The Engaging with the Natural Journal of second hypothesis asserted that environmental identity would also be a significant indicator and the third hypothesis stated that 146 2/2/2009 Environment: The Role of Environmental 28, 2 109-120 participants from rural environments would have higher ratings of affective connection, behavioral intentions, and attitudes. -

Table of Contents (PDF)

VOL. 178 Խ NO. 6 Խ March 15, 2007 Խ Pages 3343–4002 IMMUNOLOGY OF TABLE OF CONTENTS 3343 In This Issue Brief Reviews 3345 Maternal Acceptance of the Fetus: True Human Tolerance Indira Guleria and Mohamed H. Sayegh Cutting Edge 3353 Cutting Edge: Acute and Chronic Exposure of Immature B Cells to Antigen Leads to Impaired Homing and SHIP1-Dependent Reduction in Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 Responsiveness Anne Brauweiler, Kevin Merrell, Stephen B. Gauld, and John C. Cambier 3358 Cutting Edge: Chemokine Receptor CCR4 Is Necessary for Antigen-Driven Cutaneous Accumulation of OURNAL CD4 T Cells under Physiological Conditions J James J. Campbell, Daniel J. O’Connell, and Marc-Andre´ Wurbel 3363 Cutting Edge: Antibody-Mediated TLR7-Dependent Recognition of Viral RNA THE Jennifer P. Wang, Damon R. Asher, Melvin Chan, Evelyn A. Kurt-Jones, and Robert W. Finberg 3368 Cutting Edge: Influenza A Virus Activates TLR3-Dependent Inflammatory and RIG-I-Dependent Antiviral Responses in Human Lung Epithelial Cells Ronan Le Goffic, Julien Pothlichet, Damien Vitour, Takashi Fujita, Eliane Meurs, Michel Chignard, and Mustapha Si-Tahar 3373 Cutting Edge: Proinflammatory and Th2 Cytokines Synergize to Induce Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Production by Human Skin Keratinocytes Sofia I. Bogiatzi, Isabel Fernandez, Jean-Christophe Bichet, Marie-Annick Marloie-Provost, Elisabetta Volpe, Xavier Sastre, and Vassili Soumelis Cellular Immunology and Immune Regulation 3379 The Fas/Fas Ligand System Inhibits Differentiation of Murine Osteoblasts but Has a Limited Role in Osteoblast and Osteoclast Apoptosis Natasˇa Kovac˘ic´, Ivan Kresˇimir Lukic´, Danka Grc˘evic´, Vedran Katavic´, Peter Croucher, and Ana Marusˇic´ 3390 Serpin-6 Expression Protects Embryonic Stem Cells from Lysis by Antigen-Specific CTL Zeinab Abdullah, Tomo Saric, Hamid Kashkar, Nikola Baschuk, Benjamin Yazdanpanah, Bernd K. -

Name Clustering on the Basis of Parental Preferences Gerrit Bloothooft and Loek Groot Utrecht University, the Netherlands

names, Vol. 56, No. 3, September, 2008, 111–163 Name Clustering on the Basis of Parental Preferences Gerrit Bloothooft and Loek Groot Utrecht University, The Netherlands Parents do not choose fi rst names for their children at random. Using two large datasets, for the UK and the Netherlands, covering the names of children born in the same family over a period of two decades, this paper seeks to identify clusters of names entirely inferred from common parental naming preferences. These name groups can be considered as coherent sets of names that have a high probability to be found in the same family. Operational measures for the statistical association between names and clusters are developed, as well as a two-stage clustering technique. The name groups are subsequently merged into a limited set of grand clusters. The results show that clusters emerge with cultural, linguistic, or ethnic parental backgrounds, but also along characteristics inherent in names, such as clusters of names after fl owers and gems for girls, abbreviated names for boys, or names ending in –y or -ie. Introduction The variety in personal given names has increased enormously over the past century. In the Netherlands, the top 3, top 10, and top 100 names account, respectively, for 16%, 33%, and 70% of the fi rst names of elderly born between 1910 and 1930, while these fi gures are 3%, 8%, and 39% for babies born between 2000 and 2004. Compa- rable fi gures are presented by Galbi (2002, 4) for England and Wales. Along with the increase in the variety in names, the motives behind the choice of names for children by their parents have changed from a more or less prescribed naming after relatives to a free decision, a process that was facilitated in the Netherlands by the tolerant name law of 1970. -

Meisjes C MC3 1

Meisjes C MC3 1 Louise Bartels C03 2 Elise Bogaards C03 3 Emma Dam C03 4 Sophie Fijnheer C03 5 Lieke Kerstjens C03 6 Nina van der Leest C03 7 Brit van der Meijden C03 8 Iris Nikerk C03 9 Willemijn van Oord C03 KEEPER 10 Julia Schellekens C03 11 Kim Stranders C03 12 Guillemette Verdonk C03 13 Noor Vrouwenraets C03 14 Maxine van Walbeek C03 MC4 1 Willemijn Abbenhuis C04 2 Pien van den Berkmortel C04 3 Floor Cornelissen C04 4 Rebecca Hietink C04 5 Anne Hooftman C04 6 Fabiënne van Lun C04 7 Nora Nooter C04 KEEPER 8 Margaux van Overvest C04 9 Aline van Rijswijk C04 10 Ruth Ruskamp C04 11 Romee Schrijver C04 12 Imke Sonnemans C04 13 Rachel Steenbrink C04 14 Laurine Stodel C04 15 Merel Vosters C04 MC5 1 Charlotte de Bekker C05 2 Janne van den Berkmortel C05 3 Katharina Boekhorst C05 4 Laura Borchers C05 5 Noor Botenga C05 6 Feline van der Eijk C05 7 Valérie Heidman C05 8 Puck Janssen C05 9 Evelien van der Laan C05 10 Quirine Moolenaar C05 11 Coos van Raalte C05 12 Carlijn Smulders C05 13 Marie-Elske van der Vat C05 14 Simone Vis C05 MC6 1 Marilou Bartels C06 2 Femke van Beyma C06 3 Constance Bosland C06 4 Margot van Doorn C06 5 Babette van Giersbergen C06 6 Sharon Groen C06 7 Maud van Loon C06 8 Lise Lot Ridderbos C06 9 Eva Schlösser C06 10 Margot Sieburgh C06 11 Barbara Slooff C06 12 Josephine Wesseling C06 13 Sarah Alice van der Wielen C06 14 Lotte van Wijngaarden C06 MC7 1 Suzanne van Baarle C07 2 Liesje Bloembergen C07 3 Olivia de Cuba C07 4 Noémie Dickmann C07 5 Fleur Gieskes C07 6 Karlijn Lange C07 7 Eva Mollema C07 8 Susanne Musters C07 -

Free Tips for Searching Ancestors' Surnames

SURNAMES: FAMILY SEARCH TIPS AND SURNAME ORIGINS Picking a name Naming practices developed differently from region to region and country to country. Yet even today, hereditary The Name Game names tend to fall into one of four categories: patronymic Onomastics, a field of linguistics, is the study of names and (named from the father), occupational, nickname or place naming practices. The American Name Society (ANS) was name. According to Elsdon Smith, author of American Sur- founded in 1951 to promote this field in the United States and names (Genealogical Publishing Co.), a survey of some 7,000 abroad. Its goal is to “find out what really is in a name, and to surnames in America revealed that slightly more than 43 investigate cultural insights, settlement history and linguistic percent of our names derive from places, followed by about characteristics revealed in names.” 32 percent from patronymics, 15 percent from occupations The society publishes NAMES: A Journal of Onomastics, and 9 percent from nicknames. a quarterly journal; the ANS Bulletin; and the Ehrensperger Often the lines blur between the categories. Take the Report, an annual overview of member activities in example of Green. This name could come from one’s clothing onomastics. The society also offers an online discussion or it could be given to one who was inexperienced. It could group, ANS-L. For more information, visit the ANS website at also mean a dweller near the village green, be a shortened <www.wtsn.binghamton.edu/ANS>. form of a longer Jewish or German name, or be a translation from another language.