1968Apjs...15..131G OH ABSORPTION in the GALAXY* W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae

Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae By Dave Knisely Light Pollution and various “nebula” filters have been around since the late 1970’s, and amateurs have been using them ever since to bring out detail (and even some objects) which were difficult to impossible to see before in modest apertures. When I started using them in the early 1980’s, specific information about which filter might work on a given object (or even whether certain filters were useful at all) was often hard to come by. Even those accounts that were available often had incomplete or inaccurate information. Getting some observational experience with the Lumicon line of filters helped, but there were still some unanswered questions. I wondered how the various filters would rank on- average against each other for a large number of objects, and whether there was a “best overall” filter. In particular, I also wondered if the much-maligned H-Beta filter was useful on more objects than the two or three targets most often mentioned in publications. In the summer of 1999, I decided to begin some more comprehensive observations to try and answer these questions and determine how to best use these filters overall. I formulated a basic survey covering a moderate number of emission and planetary nebulae to obtain some statistics on filter performance to try to address the following questions: 1. How do the various filter types compare as to what (on average) they show on a given nebula? 2. Is there one overall “best” nebula filter which will work on the largest number of objects? 3. -

Supernova Shocks in Molecular Clouds: Velocity Distribution of Molecular Hydrogen William T

Draft version September 6, 2019 Typeset using LATEX preprint2 style in AASTeX63 Supernova Shocks in Molecular Clouds: Velocity Distribution of Molecular Hydrogen William T. Reach,1 Le Ngoc Tram,1 Matthew Richter,2 Antoine Gusdorf,3 Curtis DeWitt,1 1Universities Space Research Association, MS 232-11, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 2University of California, Davis, CA USA 3Observatoire de Paris, Ecole´ normale sup´erieure, Sorbonne Universit´e,CNRS, LERMA, 75005 Paris, France ABSTRACT Supernovae from core-collapse of massive stars drive shocks into the molecular clouds from which the stars formed. Such shocks affect future star formation from the molecu- lar clouds, and the fast-moving, dense gas with compressed magnetic fields is associated with enhanced cosmic rays. This paper presents new theoretical modeling, using the Paris-Durham shock model, and new observations at high spectral resolution, using the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), of the H2 S(5) pure rota- tional line from molecular shocks in the supernova remnant IC 443. We generate MHD models for non-steady-state shocks driven by the pressure of the IC 443 blast wave into gas of densities 103 to 105 cm−3. We present the first detailed derivation of the shape of the velocity profile for emission from H2 lines behind such shocks, taking into account the shock age, preshock density, and magnetic field. For preshock densities 103{105 −3 cm , the H2 emission arises from layers that extend 0.01{0.0003 pc behind the shock, respectively. The predicted shifts of line centers, and the line widths, of the H2 lines range from 20{2, and 30{4 km s−1, respectively. -

How to Make $1000 with Your Telescope! – 4 Stargazers' Diary

Fort Worth Astronomical Society (Est. 1949) February 2010 : Astronomical League Member Club Calendar – 2 Opportunities & The Sky this Month – 3 How to Make $1000 with your Telescope! – 4 Astronaut Sally Ride to speak at UTA – 4 Aurgia the Charioteer – 5 Stargazers’ Diary – 6 Bode’s Galaxy by Steve Tuttle 1 February 2010 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 Algol at Minima Last Qtr Moon Æ 5:48 am 11:07 pm Top ten binocular deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2244, NGC 2264, NGC 2301, NGC 2360 Top ten deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2261, NGC 2362, NGC 2392, NGC 2403 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Algol at Minima Morning sports a Moon at Apogee New Moon Æ super thin crescent (252,612 miles) 8:51 am 7:56 pm Moon 8:00 pm 3RF Star Party Make use of the New Moon Weekend for . better viewing at the Dark Sky Site See Notes Below New Moon New Moon Weekend Weekend 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Presidents Day 3RF Star Party Valentine’s Day FWAS Traveler’s Guide Meeting to the Planets UTA’s Maverick Clyde Tombaugh Ranger 8 returns Normal Room premiers on Speakers Series discovered Pluto photographs and NatGeo 7pm Sally Ride “Fat Tuesday” Ash Wednesday 80 years ago. impacts Moon. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Algol at Minima First Qtr Moon Moon at Perigee Å (222,345 miles) 6:42 pm 12:52 am 4 pm {Low in the NW) Algol at Minima Æ 9:43 pm Challenge binary star for month: 15 Lyncis (Lynx) Challenge deep-sky object for month: IC 443 (Gemini) Notable carbon star for month: BL Orionis (Orion) 28 Notes: Full Moon Look for a very thin waning crescent moon perched just above and slightly right of tiny Mercury on the morning of 10:38 pm Feb. -

A Multispectral Analysis of the Northeastern Shell of IC 443

MNRAS 000,1–13 (2019) Preprint 13 August 2019 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 A multispectral analysis of the northeastern shell of IC 443 Alexandre Alarie,1;2;3 Laurent Drissen,2;3 1 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad National Autónoma de México, Apdo. Postal 70264, 04510 Mexico D.F., Mexico 2 Département de physique, de génie physique et d’optique, Université Laval, Québec, QC, G1V 0A6, Canada 3 Centre de Recherche en Astrophysique du Québec 13 August 2019 ABSTRACT We have carried out optical observations of the north-eastern part of the supernova remnant IC 443 using the CFHT imaging spectrograph SITELLE. The observations consist of three multispectral cubes covering an 110 ×110 area allowing the investigation of both the spatial and spectral variation of 9 emission lines : [O II] ll3726+3729, [O III] ll4959,5007, Hb, Ha, [N II] ll6548,6583 and [S II] ll6716,6731. Extinction measurement from the Ha/Hb shows significant variation across the observed region with E(B-V) = 0.8-1.1. Electron density measurements using [S II] lines indicate densities ranging from 100 up to 2500 cm−3. Models computed with the shock modelling code MAPPINGS are presented and compared with the observations. A combination of complete shock model and truncated ones are required in order to explain the observed spectrum. The shock velocities found in IC 443 are between 20 and 150 km s−1 with 75 km s−1 being the most prominent velocity. The pre-shock number density varies from 20 to 60 cm−3. A single set of abundances close to solar values combined with varying shock parameters (shock velocity, pre-shock density and shock age) are sufficient to explain the great variation of lines intensities observed in IC 443. -

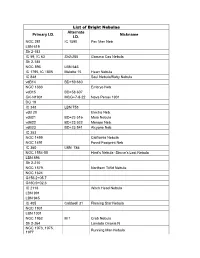

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Early Stages of Massive Star Formation

Early Stages of Massive Star Formation Vlas Sokolov Munchen¨ 2018 Early Stages of Massive Star Formation Vlas Sokolov Dissertation an der Fakultat¨ fur Physik der Ludwig–Maximilians–Universitat¨ Munchen¨ vorgelegt von Vlas Sokolov aus Kyjiw, Ukraine Munchen,¨ den 13 Juli 2018 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Paola Caselli Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Markus Kissler-Patig Tag der mundlichen¨ Prufung:¨ 27 August 2018 Contents Zusammenfassung xv Summary xvii 1 Introduction1 1.1 Overview......................................1 1.2 The Interstellar Medium..............................2 1.2.1 Molecular Clouds..............................5 1.3 Low-mass Star Formation..............................9 1.4 High-Mass Star and Cluster Formation....................... 12 1.4.1 Observational perspective......................... 14 1.4.2 Theoretical models............................. 16 1.4.3 IRDCs as the initial conditions of massive star formation......... 18 1.5 Methods....................................... 20 1.5.1 Radio Instrumentation........................... 20 1.5.2 Radiative Processes in the Dark Clouds.................. 22 1.5.3 Blackbody Dust Emission......................... 23 1.5.4 Ammonia inversion transitions....................... 26 1.6 This Thesis..................................... 28 2 Temperature structure and kinematics of the IRDC G035.39–00.33 31 2.1 Abstract....................................... 31 2.2 Introduction..................................... 32 2.3 Observations.................................... 33 2.3.1 GBT observations............................ -

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Studies of Particle Acceleration in Supernova Remnants

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Studies of Particle Acceleration in Supernova Remnants Takaaki Tanaka (KIPAC, Stanford University) Fermi LAT results presented on behalf of the Fermi LAT collaboration Teraelectronvolt Astronomy 37 SNRs = Cosmic-Ray Sources? Supernova remnants have been thought to be accelerating cosmic rays up to the knee (PeV) thorough the diffusive shock acceleration mechanism Synchrotron X-rays and TeV gamma rays from SNRs = Evidence of acceleration up to TeV energies SN 1006 Chandra H.E.S.S. 30′ Figure 6: Four SNRs imaged in (dominantly) non-thermal X-rays (left) and resolved in VHE γ-rays with H.E.S.S. (right). a) RX J1713.7 3946 with 1–3 keV data from ASCA (Uchiyama, Takahashi & Aharonian −2002), b) RX J0852.0 4622 with ROSAT (1.3–2.4 keV) (Aschenbach 1998), c) RCW86 with− 2–4 keV data from XMM-Newton (Vinketal. 2006) d) SN 1006 with Chandra archive data (0.5–10 keV). The H.E.S.S. data are taken from Aharonian et al. (2006b, 2007d), Aharonian & etal.(2008), Naumann-Godo & et al. (2006). The white scale bars are 0.5◦ long. Suzaku (XIS + HXD) Results ① Suzaku has been probing electrons accelerated in SNRs through XIS + HXD measurements of synchrotron X-rays ① RX J1713.7–3946 (Takahashi+ 2008; Tanaka+ 2008) ② Tycho (Tamagawa+ 2009) ③ Cassiopeia A (Maeda+ 2009) No. S1] Suzaku Observations of Tycho’s SNR S173 No. 6] Possible keV–TeV Correlation in the Reverse Shock 1223 ② ③ Fig. 8. (a) XIS and PIN spectra fitted with a thermal bremsstrahlung, an srcut model, and GaussianFig. lines. -

The Galaxy in Context: Structural, Kinematic & Integrated Properties

The Galaxy in Context: Structural, Kinematic & Integrated Properties Joss Bland-Hawthorn1, Ortwin Gerhard2 1Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics A28, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia; email: [email protected] 2Max Planck Institute for extraterrestrial Physics, PO Box 1312, Giessenbachstr., 85741 Garching, Germany; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2016. Keywords 54:529{596 Galaxy: Structural Components, Stellar Kinematics, Stellar This article's doi: 10.1146/annurev-astro-081915-023441 Populations, Dynamics, Evolution; Local Group; Cosmology Copyright c 2016 by Annual Reviews. Abstract All rights reserved Our Galaxy, the Milky Way, is a benchmark for understanding disk galaxies. It is the only galaxy whose formation history can be stud- ied using the full distribution of stars from faint dwarfs to supergiants. The oldest components provide us with unique insight into how galaxies form and evolve over billions of years. The Galaxy is a luminous (L?) barred spiral with a central box/peanut bulge, a dominant disk, and a diffuse stellar halo. Based on global properties, it falls in the sparsely populated \green valley" region of the galaxy colour-magnitude dia- arXiv:1602.07702v2 [astro-ph.GA] 5 Jan 2017 gram. Here we review the key integrated, structural and kinematic pa- rameters of the Galaxy, and point to uncertainties as well as directions for future progress. Galactic studies will continue to play a fundamen- tal role far into the future because there are measurements that can only be made in the near field and much of contemporary astrophysics depends on such observations. 529 Redshift (z) 20 10 5 2 1 0 1012 1011 ) ¯ 1010 M ( 9 r i 10 v 8 M 10 107 100 101 102 ) c p 1 k 10 ( r i v r 100 10-1 0.3 1 3 10 Time (Gyr) Figure 1 Left: The estimated growth of the Galaxy's virial mass (Mvir) and radius (rvir) from z = 20 to the present day, z = 0. -

The Supernova Remnant W49B As Seen with H.E.S.S

PUBLISHED VERSION H.E.S.S. Collaboration: H. Abdalla … R. Blackwell … P. DeWilt … J. Hawkes … J. Lau … N. Maxted … G. Rowell … F. Voisin … et al. The supernova remnant W49B as seen with H.E.S.S. and Fermi-LAT Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2018; 612:A5-1-A5-10 © ESO 2018 Originally published: http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201527843 PERMISSIONS https://www.aanda.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=863&Itemid=2 95 Green Open Access The Publisher and A&A encourage arXiv archiving or self-archiving of the final PDF file of the article exactly as published in the journal and without any period of embargo. 19 September 208-18 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/112084 A&A 612, A5 (2018) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527843 & c ESO 2018 Astrophysics H.E.S.S. phase-I observations of the plane of the Milky Way Special issue The supernova remnant W49B as seen with H.E.S.S. and Fermi-LAT? H.E.S.S. Collaboration: H. Abdalla1, A. Abramowski2, F. Aharonian3,4,5, F. Ait Benkhali3, A. G. Akhperjanian5; 6,y, T. Andersson10, E. O. Angüner7, M. Arrieta15, P. Aubert24, M. Backes8, A. Balzer9, M. Barnard1, Y. Becherini10, J. Becker Tjus11, D. Berge12, S. Bernhard13, K. Bernlöhr3, R. Blackwell14, M. Böttcher1, C. Boisson15, J. Bolmont16, P. Bordas3, J. Bregeon17, F. Brun26,??, P. Brun18, M. Bryan9, T. Bulik19, M. Capasso29, J. Carr20, S. Casanova21,3, M. Cerruti16, N. Chakraborty3, R. Chalme-Calvet16, R.C. G. Chaves17,22, A. Chen23, J. Chevalier24, M. Chrétien16, S. -

The X-Ray Structure and Spectrum of the Pulsar Wind Nebula Surrounding PSR B1853+01 in W44

The X-ray Structure and Spectrum of the Pulsar Wind Nebula Surrounding PSR B1853+01 in W44 R. Petre, K. D. Kuntz 1 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 and R. L. Shelton The Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218 ABSTRACT We present the result of a Chandra ACIS observation of the pulsar PSR B1853+01 and its associated pulsar wind nebula (PWN), embedded within the supernova remnant W44. A hard band ACIS map cleanly distinguishes the PWN from the thermal emission of W44. The nebula is extended in the north-south direction, with an extent about half that of the radio emission. Morphological differences between the X-ray and radio images are apparent. Spectral fitting reveals a clear difference in spectral index between the hard emission from PSR B1853+01 (F --_ 1.4) and the extended nebula (F --, 2.2). The more accurate values for the X-ray flux and spectral index are used refine estimates for PWN parameters, including magnetic field strength, the average Lorentz factor _ of the particles in the wind, the magnetization parameter a, and the ratio k of electrons to other particles. Subject headings: supernova remnants--ISM:individual(W 44)--X-rays:general 1. Introduction fated, old radio pulsars. Additionally, because of its high proper motion, the pulsar leaves a record The remarkable pulsar wind nebula associated of its evolution embedded in the extended neb- with PSR B1853+01 and embedded in the evolved, ula. A combination of high resolution radio and mixed-morphology supernova remnant W44 is of X-ray observations can potentially disentangle this particular interest for several reasons. -

Pga 183525.Pdf

Condensed Technical Program USNC/URSI 15-19 May 1978 MONDAY, 15 MAY Room 0900-1200 B-1 Electromagnetics 0105 B-2 SEM 0109 E-1 Lightning, Spherics and Noise (Joint with F and H) 1105 1330-1700 B-3 Thin Wires 0105 B-4 Inverse Scattering and Profile Reconstruction 0109 E-2 CCIR Panel Discussion (Joint with F) 1105 F-1 Oceanography 1109 1700 Commission E Business Meeting 1105 1715 Commission B Business Meeting 0105 TUESDAY, 16 MAY 0830-1200 B-5 Scattering 0109 C-1 Impairments to Earth-Satellite Transmission 1101 F-2 Remote Sensing of the Atmosphere from Space 1109 1330-1700 B-6 Transmission Lines 0109 C-2 System Aspects of Antennas and Dual Polarization 1101 Transmission F-3 Scattering by Random Media and Rough Surfaces (Joint with 1109 AP-S and B) G-1 HF Radio Wave Absorption and Heating Effects 0123 1700 Commission C Business Meeting 1101 Commission F Business Meeting 0123 Commission H Business Meeting 0123 (continued on inside back cover) United States National Connnittee INTERNATIONAL UNION.OF RADIO SCIENCE PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1978 Spring Meeting May 15-19 Held Jointly with ANTENNAS AND PROPAGATION SOCIETY INSTITUTE OF ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS ENGINEERS Washington, D.C. ]!Q:!!: Programs and Abstracts of the USNC/URSI Meetings are available from: USNC/URSI National Academy of Sciences 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20418 at $2 for meetings prior to 1970, $3 for 1971-75 meetings, and $5 for 1976-78 meetings. The full papers are not published in any collected format; requests for them should be addressed to the authors who may have them published on their own initiative. -

VI. Dense Gas and Mini-Starbursts in the W43 Giant Molecular Cloud Complex

Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan (2014) 00(0), 1–42 1 doi: 10.1093/pasj/xxx000 FOREST Unbiased Galactic plane Imaging survey with the Nobeyama 45 m telescope (FUGIN). VI. Dense gas and mini-starbursts in the W43 giant molecular cloud complex Mikito KOHNO1∗ ∗ , Kengo TACHIHARA1∗, Kazufumi TORII2∗, Shinji FUJITA1,3∗, Atsushi NISHIMURA1,3, Nario KUNO4,5,12, Tomofumi UMEMOTO2,6, Tetsuhiro MINAMIDANI2,6,7, Mitsuhiro MATSUO2, Ryosuke KIRIDOSHI3, Kazuki TOKUDA3,7, Misaki HANAOKA1, Yuya TSUDA8, Mika KURIKI4, Akio OHAMA1, Hidetoshi SANO1,7,9, Tetsuo HASEGAWA7, Yoshiaki SOFUE10, Asao HABE11, Toshikazu ONISHI3 and Yasuo FUKUI1,9 1Department of Physics, Graduate School of Science, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8602, Japan 2Nobeyama Radio Observatory, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS), 462-2, Nobeyama, Minamimaki, Minamisaku, Nagano 384-1305, Japan 3Department of Physical Science, Graduate School of Science, Osaka Prefecture University, 1-1 Gakuen-cho, Naka-ku, Sakai, Osaka 599-8531, Japan 4Department of Physics, Graduate School of Pure and Applied Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Ten-nodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8577, Japan 5Tomonaga Center for the History of the Universe, University of Tsukuba, Ten-nodai 1-1-1, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8571, Japan 6Department of Astronomical Science, School of Physical Science, SOKENDAI (The Graduate University for Advanced Studies), 2-21-1, Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan 7National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ),