First 3 Chapters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crew Members: AJ-F (For Freddie)

April 2019 Issue 01 VM1904C This is the first time we have had such a fantastic selection of signed Dambuster covers. I have included each crew member, even though some may not have signed. I am sure many of you will not be able to resist!! On the night of 16-17 May 1943, Wing Commander Guy Gibson led 617 Squadron, later called the Dambusters, of the Royal Air Force on a bombing raid to destroy three dams in the Ruhr valley, the industrial heartland of Germany. The mission was codenamed Operation ‘Chastise’. The dams were fiercely protected. Torpedo nets in the water stopped underwater attacks and anti-aircraft guns defended them against enemy bombers. But 617 Squadron had a secret weapon: the ‘bouncing bomb’, which was developed by Barnes Wallis. The surviving aircrew of 617 Squadron were lauded as heroes, and Guy Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions during the raid. The raid also established 617 Squadron as a specialist precision bombing unit, experimenting with new bomb sights, target marking techniques and colossal new ‘earthquake’ bombs developed by Barnes Wallis. AJ-F (for Freddie) RYD617FN £75 Our choice of Crew Members: cover, signed by Dudley P Heal. F/Sgt Kenneth Brown CGM (Pilot), Sgt Harold B Feneron (Engineer), Sgt Dudley P Heal DFM (Navigator), Sgt H J Hewstone (Wireless Operator), Sgt S Oancia (Bomb Aimer), Sgt D Allaston (Front Gunner), F/Sgt Grant S MacDonald (Rear Gunner). RYD617FR £100 Our choice of cover signed by F/Sgt Grant S MacDonald. £50 per month over 2 months RYD617FRB £100 £50 per month over 2 months RYD617FRA £100 2007 Operation 2007 Formation of 617 Squadron. -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Didcot Railway CENTRE

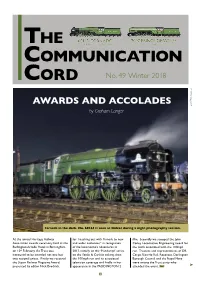

THE COMMUNICATION ORD No. 49 Winter 2018 C Shapland Andrew AWARDS AND ACCOLADES by Graham Langer Tornado in the dark. No. 60163 is seen at Didcot during a night photography session. At the annual Heritage Railway for “reaching out with Tornado to new film. Secondly we scooped the John Association awards ceremony held at the and wider audiences” in recognition Coiley Locomotive Engineering award for Burlington Arcade Hotel in Birmingham of the locomotive’s adventures in the work associated with the 100mph on 10th February, the Trust was 2017, initially on the ‘Plandampf’ series run. Trustees and representatives of DB honoured to be awarded not one but on the Settle & Carlisle railway, then Cargo, Ricardo Rail, Resonate, Darlington two national prizes. Firstly we received the 100mph run and its associated Borough Council and the Royal Navy the Steam Railway Magazine Award, television coverage and finally in her were among the Trust party who ➤ presented by editor Nick Brodrick, appearance in the PADDINGTON 2 attended the event. TCC 1 Gwynn Jones CONTENTS EDItorIAL by Graham Langer PAGE 1-2 Mandy Gran Even while Tornado Awards and Accolades up his own company Paul was Head of PAGE 3 was safely tucked Procurement for Northern Rail and Editorial up at Locomotive previously Head of Property for Arriva Tornado helps Blue Peter Maintenance Services Trains Northern. t PAGE 4 in Loughborough Daniela Filova,´ from Pardubice in the Tim Godfrey – an obituary for winter overhaul, Czech Republic, joined the Trust as Richard Hardy – an obituary she continued to Assistant Mechanical Engineer to David PAGE 5 generate headlines Elliott. -

Cat No Ref Title Author 3170 H3 an Airman's

Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 3170 H3 An Airman's Outing "Contact" 1842 B2 History of 607 Sqn R Aux AF, County of 607 Sqn Association 607 RAAF 2898 B4 AAF (Army Air Forces) The Official Guide AAF 1465 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 2504 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 790 B3 Post War Yorkshire Airfields Abraham, Barry 2654 C3 On the Edge of Flight - Development and Absolon, E W Engineering of Aircraft 3307 H1 Looking Up At The Sky. 50 years flying with Adcock, Sid the RAF 1592 F1 Burning Blue: A New History of the Battle of Addison, P/Craig JA Britain (The) 942 F5 History of the German Night Fighter Force Aders, Gerbhard 1917-1945 2392 B1 From the Ground Up Adkin, F 462 A3 Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Aero Publishers' Staff 961 A1 Pictorial Review Aeroplane 1190 J5 Aeroplane 1993 Aeroplane 1191 J5 Aeroplane 1998 Aeroplane 1192 J5 Aeroplane 1992 Aeroplane 1193 J5 Aeroplane 1997 Aeroplane 1194 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1195 J5 Aeroplane 1990 Aeroplane Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 1196 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1197 J5 Aeroplane 1989 Aeroplane 1198 J5 Aeroplane 1991 Aeroplane 1200 J5 Aeroplane 1995 Aeroplane 1201 J5 Aeroplane 1996 Aeroplane 1525 J5 Aeroplane 1974 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1526 J5 Aeroplane 1975 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1527 J5 Aeroplane 1976 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1528 J5 Aeroplane 1977 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1529 J5 Aeroplane 1978 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1530 J5 Aeroplane 1979 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1531 J5 Aeroplane 1980 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1532 J5 Aeroplane 1981 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1533 J5 -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

THE TRAINMASTER NON-PROFIT ORG ANIZATION Room 1, Union Station 800 NW 6Th Avenue US POSTAG E Portland, Oregon 97209 PAID Portland, Oregon Permit No

THE TRAINMASTER NON-PROFIT ORG ANIZATION Room 1, Union Station 800 NW 6th Avenue US POSTAG E Portland, Oregon 97209 PAID Portland, Oregon Permit No. 595 ADDRESS CORRECTION REQUESTED TIM E VALUE MAIL PACIFIC NORTHWEST CHAPTER NATIONAL RAILWAY HISTORICAL SOCIETY,! (an Oregon Non-Profit Corporation) ., . :.� � . � � 1975 CHAPTER OFFICERS president director-at-Iarge EDWARD E IMMEL (503) 233-9706 IRVING G EWEN (503) 232-2441 3124 S E Taylor Street 4128 N E 76th Avenue Portland, Oregon - 97214 Portland, Oregon - 97218 vice-president director-at-Iarge WALTER R GRANDE 246-3254 CORA JACKSON 774-3802 4243 S.w. Admiral Street 5825 S E Lambert Street Portland, Oregon - 97221 Portland, Oregon - 97206 secretary chapter director CHARLES W STORZ , JR 289-4529 ROGER W SA CKETT 644-3437 146 N E Bryant Street 11550 S W Cardinal Terr Portland, Oregon - 97211 Beaverton, Oregon - 97005 treasurer JAMES J GILMORE 246-1202 2140 S.W. Palatine Street Portland, Oregon - 97219 CHAPTER NEWS LETTER STAFF editor and publisher Articles which appear in "The Trainmaster" do IRVING G EWEN (503) 232-2441 not express the official National Railway Histor 412B N E 76ih Avenue ical Society attitude on any subject unless Portland, Oregon - 97218 specifically designated as such. circulation manager "The Trainmaster" is sent to all Chapters of the CHARLES W STORZ, JR 289-4529 National Railway Historical Society. Copies are 146 N E Bryant Street addressed to the Chapter Director if no other - 97211 Portland, Oregon address is available. Chapters wishing to have "The Trainmaster" sent to another officer or the Chapter editor should write to the circulation All exchange news letters should be sent to manager as listed above. -

TTGGMC Newsletter

Tea Tree Gully Gem & Mineral Club Inc. (TTGGMC) April Clubrooms: Old Tea Tree Gully School, Dowding Terrace, Tea Tree Gully, SA 5091. Edition Postal Address: Po Box 40, St Agnes, SA 5097. President: Ian Everard. H: 8251 1830 M: 0417 859 443 Email: [email protected] 2016 Secretary: Claudia Gill. M: 0419 841 473 Email: [email protected] Treasurer: Russell Fischer. Email: [email protected] "Rockzette" Tea Tree Gully Gem & Mineral Club News In This Edition… President’s Report Meetings, Courses & Fees. Hi All, Diary Dates Meetings Don McColl is doing a presentation on, st Stop Press Club meetings are held on the 1 Thursday of Harts Range, N.T.; hope you all can make President's Report. each month except January: Club Activities. it. Apologies from Janet, Mel and myself Committee meetings start at 7.00 pm. General Meetings, Courses & Fees. for the April meeting as we will be on our meetings - arrive at 7.30 pm for 8.00 pm start. Member’s Mineral Purchases. way to the Canberra ‘Rockswap’. ‘Shell Grotto’ Article. Cheers, Ian. Faceting (times to be advised) General Interest - Workshops. Course 10 weeks x 2 hours Cost $20.00. General Interest – ‘Flying Scotsman’, Handy Club Activities Use of equipment $1.00 per hour. Hints, and Nancy’s Travel Poem. Lapidary (Tuesday mornings) Members Notice Board Competitions Course 5 weeks x 2 hours Cost $10.00. Competitions have been suspended indefinitely and are currently replaced Use of equipment $1.00 per hour. Diary Dates with members showcasing an interesting Silver Craft (Friday mornings) part of their collection. -

Proud to Sponsor Canterbury Festival

CANTERBURY FESTIVAL KENT’S INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 20 OCT - 3 NOV 2018 canterburyfestival.co.uk i Welcome & Sponsors Box Office: 01227 787787 canterburyfestival.co.uk WELCOME PARTNER AND PRINCIPAL SPONSOR FUNDERS from Rosie Turner Festival Director Per ardua ad astra (through struggle to the stars) has been our watchword in preparing this Canterbury Christ Church University welcomes the SPONSORS year’s star-studded Festival. opportunity to work with Canterbury Festival in 2018, for the ninth consecutive year. We are delighted to be Massive thanks to our sponsors and associated with such a prestigious and popular event in donors – led by Canterbury Christ the city, as both Principal Sponsor and Partner. Church University – who have stayed Venue Sponsor loyal, increased their commitment, Canterbury Festival plays both a vital role in the city’s or joined us for the first time, proving excellent cultural programme and the UK festival that Canterbury needs, loves and calendar. It brings together the people of Canterbury, deserves a fantastic Festival. Now visitors, and international artists in an annual celebration you can support us by booking early, of arts and culture, which contributes to a prosperous telling your friends, organising a and more vibrant city. This year’s Festival promises to work’s night out… we need to sell be as ambitious and inspirational as ever, with a rich Technical Sponsor more tickets than ever before and and varied programme. there’s lots to tempt you. The University is passionate about, and contributes From Knights and Dames to significantly to, the region’s creative economy. We are performing Socks – please look proud to work closely with a range of local and national through the entire programme as cultural organisations, such as the Canterbury Festival, some of our unique events defy to collectively offer an artistically vibrant, academically simple classification. -

Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Fox, K. (2019) Paddy the Cope, Michael Powell and the story of the unmade film. Donegal Annual: Journal of the Donegal Historical Society. (In Press) Link to official URL (if available): This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Dr Ken Fox, School of Media, Art and Design, Canterbury Christ Church University Paddy the Cope, Michael Powell and the story of the unmade film. As a native of Donegal with some knowledge of Paddy the Cope’s legendary status I find myself working in a University film department housed in the Powell Building, named after Michael Powell. The opportunity to bring Donegal and Powell’s Canterbury back together again was too serendipitous to miss. The story of Paddy the Cope was another of those films which only I would want to make and which I certainly should have made (Powell, 1986: 565). Almost ten pages of the first volume of Michael Powell’s (1905-90) autobiography is taken up with the trip to Ireland in 1946, the journey on horseback from Dublin to Dungloe to meet Paddy the Cope, at least near Dungloe, as by most accounts the horses were stabled at Inver and had to be returned to their owners in Dublin. Powell’s sojourn through Ireland provided so much publicity and incident it is surprising the trek has not become the basis for some retelling in film, television, radio, prose or theatre. -

Liminal Soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger's Wartime Films

Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge To cite this version: Anita Jorge. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films. Studies in European Cinema, Intellect, 2016, 14 (1), pp.22 - 32. 10.1080/17411548.2016.1248531. hal-01699401 HAL Id: hal-01699401 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01699401 Submitted on 8 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Liminal soundscapes in Powell & Pressburger’s wartime films Anita Jorge Université de Lorraine This article explores Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s wartime films through the prism of the soundscape, focusing on the liminal function of sound. Dwelling on such films as 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942), it argues that sound acts as a diegetic tool translating the action into a spatiotemporal elsewhere, as well as a liberation tool, enabling the people threatened by Nazi assimilation to reach for a more permissive world where restrictions no longer operate. Lastly, the soundscape serves as a ‘translanguage’, bridging the gap between soldiers and civilians, or between different nations fighting against a common enemy, thus giving birth to a transnational community. -

Frederic Raphael the Glittering Prizes

FREDERIC RAPHAEL THE GLITTERING PRIZES For Stella Richman and in memory of David Gore-Lloyd CONTENTS An Early Life A Sex Life A Past Life A Country Life An Academic Life A Double Life AN EARLY LIFE 'Hullo,' Adam said, when the girl opened the door, 'it's only me. Anyone at home?' 'Only me,' she said. 'Any news?' Adam looked blank. 'News?' 'Don't be silly. From Cambridge.' 'Oh from Cambridge!' He went past her into the sitting room. 'Well, they did send me this.' He was holding out a telegram. Sheila took it from him and read it. When she looked at him again, he was grinning. 'Aren't you a pig?' she said. 'Major Scholarship! You are a pig. "They did send me this!" Pig.' He tried to put his arms round her, as if he had earned something. She was a pretty, dark girl with green eyes and a very red mouth. In 1952 most girls had very red mouths, but Sheila's mouth had a pout at once sensual and disapproving, which gave its redness a particular charm. She wore a tartan skirt with a stainless steel safety pin in it, and a white angora sweater, enchantingly tight. She disengaged herself from Adam and went, awkwardly, to the mantelpiece, where candlesticks and family pictures in silver frames were arranged with symmetrical propriety. 'So,' she said, 'the secret is out. Adam Morris is a genius.' 'It's now official, that's all. It's no news to me.' 'Three years,' Sheila said. "You know what I'd like to do now? I'd like to drive down to my dear old school in a fleet of limousines — I've now officially left incidentally, as of the aforesaid telegraphic communication - and I'd like to wrap the good news round a large brick and sling it personally through the Headmaster's window.' 'What for? He got you your scholarship, didn't he? What's your grouse?' 'What's my grouse, what's my pheasant, what's my hard-boiled egg? He only did his damnedest to stop me getting anything at all.' 'Why would he want to do that?' Sheila was turning a chocolate round and round in its crinkled paper. -

Aprèsthe 617 Squadron Moi Aircrew Association Newsletter January 2013

AprèsThe 617 Squadron Moi Aircrew Association Newsletter January 2013 Contents Editorial 2 Robertson’s Ramblings 3 The Dambusters’ Front Line 5 Happy 98th Birthday from the BBMF 7 68 Years On, Thumper Returns to the Circuit 8 Sir Barnes Wallis 125th Anniversary 11 A Flight in a Mosquito 12 Dominion Post - Magical Merlins in a Flying Machine 15 Final Landings 16 617 - Going To War With Today’s Dambusters 18 Registered Charity No 1141817 617 Sqn Aircrew Association Cover Photo: John Bell looks out from the cockpit of the BBMF Lancaster at the official unveiling after a re-paint in 617 Sqn markings. Editorial Many thanks to Jock Cochrane and especially to his wife Rachel for managing the Association’s accounts for the past few years. I am sure you will join me in wishing them an interesting and fulfilling time during Jock’s posting to Jordan. Even more thanks to Stuart Greenland for taking up the post of treasurer (just as soon as NatWest sorts its paperwork out). I would like to make a plea to all members to ensure that they pay the full subscription of £10 to ease the treasurer’s workload - it is six years since we increased the subscription from £8 and still we have members who have not updated their standing orders. The other problem we have is members not advising us when they move house or change their email address. The membership secretary, Bill Williams and I have spent the last few months chasing up members who have disappeared from our radar over recent years, and updating the membership list.