WHEN RELIGION and ORGANIZATION CONFLICT by JOHN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCSE RELIGIOUS STUDIES REVISION BOOK Year 10 Topics BELIEFS PRACTICES QUOTATION QUESTIONSS God

GCSE RELIGIOUS STUDIES REVISION BOOK Year 10 Topics BELIEFS PRACTICES QUOTATION QUESTIONSS God Omnipotent Omnipresent Omniscient Eternal Merciful Justice Immanent Transcendent Predestination Beneficence Benevolent Free Will Resurrection Day of Judgement Sin Fairness Faith Revelation Heaven Hell The 6 Articles of Faith (Sunni) The Five Roots Allah & Tawhid One God (Shi’a) Tawhid - Belief in the oneness Angels 1. One God -Tawhid of God Holy Books 2. Divine Justice - Adalat Shirk – Breaking Tawhid Prophets 3. Prophethood - Nubuwat Inshallah – If Allah wills it Day of Judgement 4. Belief in Imams -Imamate Omnipotent Predestination 5. The Day of Resurrection - Al- Omnipresent 99 Ma’ad Omniscient Eternal Merciful How does Which beliefs are the same and Just Tawhid Which of these beliefs is the most which are different to Sunni Immanent affect the important ? Islam? Transcendent life of a How does each of these beliefs Which belief is the most Creator Muslim? affect the lives of a Muslim? divisive? Why? Benevolent BELIEFS BELIEFS BELIEFS Angels Predestination What they are? Qadr. God has foreknowledge and control over a Light. Allah’s workers , mortal, hidden from person’s destiny. us Free will. A person's ability to choose how to act. What they do? Is it possible to believe in both predestination and free Worship Allah .Do what he says . Take If humans change their fate, will? What is recorded in the Allah’s word to man. then Allah would have made book of life is based on Jibra’il. God ‘s messenger. Qur’an . Mary & a mistake. Allah cannot what you chose to do. God Isa. -

Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim)

Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim) Written by Abdul-Aziz bin Abdullah bin Baz Compiled by Muhammad bin All bin Ibrahim Al-Arfaj Edited by TbtVists yUljib DARUSSALAM Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim) By Abdul-Aziz bin Abdullah bin Baz Compiled by Muhammad bin Ali bin Ibrahim Al-Arfaj Translated by Darussalam Published by DARUSSALAM Publishers & Distributors Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED &•>ja>v> A..UJ1 ti^a> **. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DARUSSALAM First Edition: October 2002 Supervised by: ABDUL MALIK MUJAHID Headquarters: Mobile: 0044-794 730 6706 P.O. Box: 22743, Riyadh 11416, KSA Fax: 0044-208 521 7645 Tel: 00966-1-4033962/4043432 • Darussalam International Publications Fax:00966-1-4021659 Limited, Regent Park Mosque, E-mail: [email protected] 146 Park Road, London NW8 7RG, Website: http://www.dar-us-salam.com Tel: 0044-207 724 3363 Bookshop: Tel: 00966-1-4614483 FRANCE Fax:00966-1-4644945 • Editions & Libairie Essalam Branches & Agents: 135, Bd de Menilmontant 7501 Paris (France) K.S.A. Tel: 01 43 381 956/4483 - Fax 01 43 574431 . Jeddah: Tel & Fax: 00966-2-6807752 Website: http: www.Essalam.com • Al-Khobar: Tel: 00966-3-8692900 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 00966-3-8691551 AUSTRALIA U.A.E. • Lakemba NSW: ICIS: Ground Floor • Tel: 00971-6-5632623 Fax: 5632624 165-171, Haldon St. PAKISTAN Tel: (61-2) 9758 4040 Fax: 9758 4030 • 50-Lower Mall, Lahore MALAYSIA Tel: 0092-42-7240024 Fax: 7354072 • E&D BOOKS SDN. -

Concepts of Social Justice: an Islamic Perspective

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol.8, No.4, 2016 Concepts of Social Justice: An Islamic Perspective Shakeel Ahmad Sofi Senior Research Fellow, Department of Management Studies, Central University of Kashmir (J&K) India Dr. Fayaz Ahmad Nika Associate Professor, Department of Management Studies,Central University of Kashmir (J&K) India Abstract Whole world is witnessing turmoil engulfed by an unending conflict and the causes may not be open to general public but it is largely rooted in the race for hegemony. This commotion will prolong till people don’t realize it and don not struggle to destroy the hegemony of evil doctrine. There are many avenues through which this doctrine can challenged and Social Justice is one such aspect which can shape the worldly affairs under one umbrella. But certain things are warranted too and it needs to be ascertained as what will determine Social Justice. The conception of Social justice finds its significance in every blissful society as no individual with human compassion would like to impair others. Different definitions and frameworks have been put forward to establish impartiality and that may govern the state of affairs of a county. But there still exist difficulty in shaping impartiality throughout the world. This paper in an attempt tries to explore the pros and cons of the manmade laws for developing impartiality and then finally outlines the framework proposed by the Almighty Allah, ‘The Lord of Lands”. The researcher has compared rules and penalties instituted by mankind and those revealed in the Book of Allah, “Al-Quran”. -

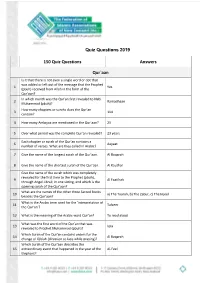

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

MCC Part Time Schools Approved Theology Syllabus (Iman, Ibadat, Akhlaq) Academic Year, 2009-10 Grade: 01 Topic Code Topic Book

MCC Part Time Schools Approved Theology Syllabus (Iman, Ibadat, Akhlaq) Academic year, 2009-10 Grade: 01 Topic Code Topic Book Iman and Ibadaat G01I01 Allah: Only one, creator, kind, loving, other attributes of Allah Islam for younger people G01I02 Allah’s creation: Hills, Mountains, Rivers, Flowers, rain, sun, moon, stars, sky Islam for younger people G01I03 Memorize Kalima Tayyiba with meanings Children’s book of Islam part 1 Islam for younger people G01I04 Memorize Kalima Shahadah with meanings Children’s book of Islam part 1 G01I05 Demonstration of Salat alone and with Jam’at, wudu, takbir, tasbih, adan, iqamah, masjid, Qibla. My coloring book of Salah Akhlaq G01A01 Respect for Allah’s creation: animals, plants and ecology, conservation of natural resources and appreciation of Allah’s bounties 106 G01A02 Cleanliness: Hands, teeth, body, clothes, room 96 G01A03 The use of washroom and washroom etiquettes My little book of Dua G01A04 Assalamu-Alaikum, Wa Alaikum Assalam with meanings My little book of Dua G01A05 Love and respect for parents and elders Islam for younger people MCC Part Time Schools Approved Theology Syllabus (Iman, Ibadat, Akhlaq) Academic year, 2009-10 Grade: 02 Topic Code Topic Book Iman and Ibadaat G02I06 The five pillars of Islam: Ash-Shahadah, Salat, Zakat, Sawm, and Hajj Children’s book of Islam (I) and (II) G02I01 Four names of Allah: Allah, Al-RAb, Al-Rahman, Al-Rahim Worship & Conduct G02I02 Angels of Allah: Jibrail, Michail, Izrail, and Israfil Islam for younger people G02I03 Names of five daily prayers My coloring book of Salah G02I04 Memorize Tashahhud Worship & Conduct G02I08 Demonstration of Salat alone and with Jam’at, wudu, takbir, tasbih, adan, iqamah, masjid, Qibla. -

Supreme Court of the United States ------ ------GREGORY HOUSTON HOLT A/K/A ABDUL MAALIK MUHAMMAD, Petitioner, V

No. 13-6827 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- GREGORY HOUSTON HOLT A/K/A ABDUL MAALIK MUHAMMAD, Petitioner, v. RAY HOBBS, DIRECTOR, ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION, ET AL., Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Eighth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS AND HUY AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JOEL WEST WILLIAMS Counsel of Record RICHARD A. GUEST STEVEN C. MOORE NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND 1514 P Street NW (Rear), Suite D Washington, DC 20005 (202) 785-4166 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae JOHN DOSSETT NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS 1516 P Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Counsel for Amicus the National Congress of American Indians GABRIEL S. GALANDA GALANDA BROADMAN, PLLC 8606 35th Avenue NW, Suite L1 Seattle, WA 98115 Counsel for Amicus Huy ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the Arkansas Department of Correction’s grooming policy violates the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000, 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc et seq. (2006), to the extent that it prohibits Petitioner from growing a one-half-inch beard in accordance with his religious beliefs. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioner is Gregory Houston Holt, a/k/a Abdul Maalik Muhammad. Respondents are six employees of the Arkansas Department of Correction: Director Ray Hobbs Chief Deputy Director Larry May Warden Gaylon Lay Major Vernon Robertson Captain Donald Tate Sergeant Michael Richardson All respondents are sued in their official capacities only. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED.................................. -

In This Issue Rejection of Innovation Dr Salah Al-Sawy: Tafsir and Fatawa Begin Your Planting in Rajab

NEWSLETTER ISSUE 112 IN THIS ISSUE REJECTION OF INNOVATION DR SALAH AL-SAWY: TAFSIR AND FATAWA BEGIN YOUR PLANTING IN RAJAB REJECTION OF INNOVATION This is the fifth hadith in our monthly series by our student Dr Neelofer Sohail on the 40 Hadith of Imam Nawawi. These short reflections are written under the guidance of our instructor Dr Muhammad Al- Rahawan. Dr Neelofer is in her second year at Mishkah, and is geriatric physician, a wife and a mother of 3 beautiful children. Imam An-Nawawi Hadith 5 Cultural practices have permeated Islam to such an extent that sometimes it is difficult to know what is from the Prophet (saw) and the salaf rather than a cultural innovation or bidaah. So what is bidaah? Linguistically, bidaah means to bring in something unprecedented. Technically, it implies a new methodology or practice. Ibn Rajab, may Allah have mercy on him, said," A bidaah is any form of worship which has no basis in the Shariah which would warrant its legislation." This hadith is a fundamental basis of our deen in guiding our outward actions. It complements the first hadith which talks about the inner aspects of an action which is intention, and adds the dimension of outward actions. The outward actions need to conform to the deen and the shariah, otherwise they will be rejected. In Surah Al Maidah: 3, Allah states "This day I have perfected and completed your religion for you, completed my favor upon you and have chosen for you Islam as your religion." In this verse, Allah is telling us directly He has given us everything we need to follow the religion completely and perfectly through the Quran and Prophet (saw). -

Milledgeville Campus - 2020 Fall Dean's List

Milledgeville Campus - 2020 Fall Dean's List Aime, Tabitha Depner, Haven Kadlec, Selah Phillips, Mikkayla Alvizo, Daniel Downie, Abigail Knight, Matthew Pritchett, Colin Amofah, Emmanuel Doyle, Dane Lamendola, Peter Pruitt, Michael Arantes, Pedro Dyer, Juliann Leslie, MacEe Ragland, Nicholas Atchison, Jasmine Edwards, Jessica Lewis, Kayley Raicovi, Anna Augustine, Gabrielle Eichelberger, James Lull, Timothy Ray, Ohm Barbaree, Christy Ester, Gabriel Lundy, De'kayla Rich, Peyton Barlow, Lora Etheridge, Brooklynn Mall, James Rott, Katharine Barnes, Caylee Evans, Caitlyn Malone, Sara Samuels, Devonta Barnes, Caytlin Ferreira, Andre Marquez de la Plata, Sydney Saunders, Maddie Bartschi, Brett Fontenot, Shelby Martinez Ibarra, Jasper Jared Scott, Andrew Bentley, Michael Fries, Timothy Mattison, Rico Seales, Tirin Benware, Trinity Garcia, Kira McDaniel, Noah Serrano, Litzi Black, Abby Gomez, Dejanira McFarlin, DeVincent Snow, Gregory Boggs, Abigail Gonzalez, Jose McKenzie, Shanell Soares, Rafaella Boutelle, Anna Gordon, Skylar McKie, Davis Song, Maalik Bridges, Kayla Grant, Dylan McKinney, Kristen Steadman, John Bringas, Omar Graves, Cassey McMichael, Kenlan Thompson, Logan Broersma, Lillyana Greene, Katelynn Meadors, Bohanon Touhami, Malek Brower, Kaitlyn Greer, Abbigail Mercier, Isaiah Turnipseed, Daniel Brown, Nicole Griffin, Carson Metrailer, Warren Tyson, Brandon Burks, Stefon Grigas, Kelsi Miller, Caleb Valdez, Brandon Burton, Tristen Grizzard, Mathew Mock, Chandler Venable, Abbie Calhoun, Jack Hall, Phebe Moore, Tristram Wagner, Jacob -

3Rd Grade Islamic Contest 2020-21

Bright Horizon Academy 3rd Grade Islamic Studies Contest 3 A 1. What kind of creatures are the angels? They are created from light and have the ability to change their appearance and are forever obedient to Allah (SWT). 3 A 2. Name some of the angels mentioned in the Qur’an or the Sunnah. , ِرضوان Ridwan , إِسرافيل Michael), Israfeel) ِميكائِيل Gabriel) , Mika-eel) ِجبريل Jibreel . ما ِلك and Maalik ? ِجبريلA 3. What are the duties of Angel Jibreel 3 He is the intermediary of Allah (SWT) to the Prophets to inform them about the instructions of Allah (SWT). ? ِميكائِيل A 4. What are the duties of Angel Mika-eel 3 He is the angel in charge of sustenance and rain. ? إِسرافيل A 5. What are the duties of Angel Israfeel 3 He is the angel who will blow the horn on the Day of Judgement. ? ما ِلك A 6. What are the duties of Angel Maalik 3 He is the angel in charge of Hell. ? ِرضوانA 7. What are the duties of Angel Ridwan 3 He is the angel in charge of Paradise. ?ال َحكيم A 8. What is the meaning of Allah’s (SWT) name, Al-Hakeem 3 The most Wise, Judicious ? الغَفَّار A 9. What is the meaning of Al-Gaffar 3 It means the Most Forgiving, the Pardoner. 3 A 10. How do you acquire knowledge about Allah (SWT) and His commands? Through the Qur’an and the traditions of the last Prophet Mohammad (S). 3 A 11. What is the first duty to Allah (SWT)? To believe in Him and submit completely to His commands. -

Ruqya Demystified Dissertation

4/1/2021 Ruqya Demystified Ruqya in the light of fiqh Naieem Mohammed Page 0 of 68 Ruqya demystified. “Allah comes to the aid of His friends and obedient slaves, but such a friendship with Allah comes with a due price, that involves Sabr, sacrifice, search for knowledge and dedication TO THE LAWS ESTABLISHED BY SHARIAH” 1 Ruqya demystified. Table of contents Title Page 1. Introduction and explanation of the Title 2 2. Ruqya adheres to the Usool of Fiqh 3 3. History and Comparison 5 4. Harut and Maroot in the light of Fiqh 5 5. Incident of Kharaym bin Faatik r.a. 11 6. Incident of Tameem Ad Daari 15 7. Symbols of Shirk and Kufr 18 8. Number and letter codes 20 9. Belief and Muslims amongst the Jinns 21 10. Disbelief of the Jinn and men amongst humans seeking refuge in the Jinn 24 11. Sawaad bin Qaarib 27 12. How does Ruqya work? 28 13. Essential Rules of Ruqya 33 14. Do not depend solely upon the information or the help of jinns 41 15. Ruling on using Jinns for Ruqya 47 16. Definitions regarding Ruqya 58 17. Brief explanation of the Authentic Methodology 59 18. The Manzil 63 19. Conclusion 65 20. Bibliography 66 2 Ruqya demystified. Introduction Explaining why the title has been chosen: Our attempt is to demystify the misnomers that are usually connected to the field of Ruqya. We have undoubtedly noticed that there is a rising number of self-proclaimed Raaqis in almost all countries, Cities, Jamaats, etc. Most of these methods practiced by these individuals follow very shady Usools or have no Usools at all. -

Religious Accommodation of Muslim Prisoners Before Holt V. Hobbs

University of Cincinnati Law Review Volume 84 Issue 1 Article 3 April 2018 Islam Incarcerated: Religious Accommodation of Muslim Prisoners Before Holt v. Hobbs Khaled A. Beydoun Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr Recommended Citation Khaled A. Beydoun, Islam Incarcerated: Religious Accommodation of Muslim Prisoners Before Holt v. Hobbs, 84 U. Cin. L. Rev. (2018) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol84/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Cincinnati Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Cincinnati College of Law Scholarship and Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beydoun: Islam Incarcerated: Religious Accommodation of Muslim Prisoners B ISLAM INCARCERATED: RELIGIOUS ACCOMMODATION OF MUSLIM PRISONERS BEFORE HOLT V. HOBBS KhaledA. Beydount I. Introduction ...................................................................................... 100 II. (Re)Building a Nation: The Nation of Islam ................................... 107 A. Origins and History ............................................................... 109 B . C ore B eliefs .......................................................................... 114 C. How Other Muslims Perceived the Nation of Islam D uring its Rise ..................................................................... 118 III. The Nation of Islam's Rise Behind -

Demystifying Islam.Pdf

Demystifying Islam Your Guide to the Most Misunderstood Religion of the 21st. Century By Dr. Ali Shehata Edited by Julie Samia Mair. JD MPH 2019 Contents Author’s Introduction Important Terms Evidences for God Allah—His Very Name Means Love Monotheism—the Bedrock of Islam The Quran – the Spoken Word of God Modern Science and the Quran The Preservation of the Quran Hadith and the Sunnah of Muhammad —the Second Divine Revelation Can Hadith be Trusted as Authentic? A Sampling of Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad Muhammad —the Messenger of God The Character and Teachings of the Prophet Muhammad Was Muhammad Prophesied In Other Scriptures? Prophet or Liar? Looking Into the Matter of Prophecy Relevance of the Prophet Muhammad Today Jesus Christ—the Revered Son of Mary in the Islamic Scriptures Why Don't Muslims believe that Jesus is God? Why Don't Muslims believe that Jesus is the Son of God? How do Muslims view Salvation? Blind Faith? Jesus in Islam The Shariah of Islam—an Often Misunderstood Complete Way of Life Distinctive Features of Islamic Law The Islamic Criminal Punishment System The Issue of “Honor Killings” Islamic State or Muslim Country – Is there a Difference? The Islamic Stance on Terrorism and War - Direct from the Sources What are the Verses from the Quran that Mention Violence and War? Is Islam the Only Religion that Sanctions War and Fighting? Does Islam Condemn Terrorism Scripturally? Is Islam a Religion of Tolerance? A Brief Word on 9/11 Women in Islam: Hidden and Glorious Past, Uncertain Present Women in Modern Day Secular