The Ethics of Disagreement in Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ablution "Wudhu"

1 2 3 بسم اهلل الرحمن الرحیم 4 5 Contents TAQULEED "Imitation" Following a Qualified Jurist ....................................................... 16 At Taharat "Purity" ........................................................................................................ 21 Natural and mixed water ................................................................................................. 21 II. under-kurr water ......................................................................................................... 22 III. Running water ............................................................................................................ 23 IV. Rain water .................................................................................................................. 24 V. Well Water .................................................................................................................. 25 Rules Regarding Waters .................................................................................................. 26 Rules concerned to the use of lavatory ........................................................................... 27 Istbra ""confirmation of emptiness ................................................................................. 30 Recommended and Disapprove acts ............................................................................... 31 Impure Things .................................................................................................................. 32 SEMEN ............................................................................................................................ -

GCSE RELIGIOUS STUDIES REVISION BOOK Year 10 Topics BELIEFS PRACTICES QUOTATION QUESTIONSS God

GCSE RELIGIOUS STUDIES REVISION BOOK Year 10 Topics BELIEFS PRACTICES QUOTATION QUESTIONSS God Omnipotent Omnipresent Omniscient Eternal Merciful Justice Immanent Transcendent Predestination Beneficence Benevolent Free Will Resurrection Day of Judgement Sin Fairness Faith Revelation Heaven Hell The 6 Articles of Faith (Sunni) The Five Roots Allah & Tawhid One God (Shi’a) Tawhid - Belief in the oneness Angels 1. One God -Tawhid of God Holy Books 2. Divine Justice - Adalat Shirk – Breaking Tawhid Prophets 3. Prophethood - Nubuwat Inshallah – If Allah wills it Day of Judgement 4. Belief in Imams -Imamate Omnipotent Predestination 5. The Day of Resurrection - Al- Omnipresent 99 Ma’ad Omniscient Eternal Merciful How does Which beliefs are the same and Just Tawhid Which of these beliefs is the most which are different to Sunni Immanent affect the important ? Islam? Transcendent life of a How does each of these beliefs Which belief is the most Creator Muslim? affect the lives of a Muslim? divisive? Why? Benevolent BELIEFS BELIEFS BELIEFS Angels Predestination What they are? Qadr. God has foreknowledge and control over a Light. Allah’s workers , mortal, hidden from person’s destiny. us Free will. A person's ability to choose how to act. What they do? Is it possible to believe in both predestination and free Worship Allah .Do what he says . Take If humans change their fate, will? What is recorded in the Allah’s word to man. then Allah would have made book of life is based on Jibra’il. God ‘s messenger. Qur’an . Mary & a mistake. Allah cannot what you chose to do. God Isa. -

Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim)

Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim) Written by Abdul-Aziz bin Abdullah bin Baz Compiled by Muhammad bin All bin Ibrahim Al-Arfaj Edited by TbtVists yUljib DARUSSALAM Explanation of Important Lessons (For Every Muslim) By Abdul-Aziz bin Abdullah bin Baz Compiled by Muhammad bin Ali bin Ibrahim Al-Arfaj Translated by Darussalam Published by DARUSSALAM Publishers & Distributors Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED &•>ja>v> A..UJ1 ti^a> **. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DARUSSALAM First Edition: October 2002 Supervised by: ABDUL MALIK MUJAHID Headquarters: Mobile: 0044-794 730 6706 P.O. Box: 22743, Riyadh 11416, KSA Fax: 0044-208 521 7645 Tel: 00966-1-4033962/4043432 • Darussalam International Publications Fax:00966-1-4021659 Limited, Regent Park Mosque, E-mail: [email protected] 146 Park Road, London NW8 7RG, Website: http://www.dar-us-salam.com Tel: 0044-207 724 3363 Bookshop: Tel: 00966-1-4614483 FRANCE Fax:00966-1-4644945 • Editions & Libairie Essalam Branches & Agents: 135, Bd de Menilmontant 7501 Paris (France) K.S.A. Tel: 01 43 381 956/4483 - Fax 01 43 574431 . Jeddah: Tel & Fax: 00966-2-6807752 Website: http: www.Essalam.com • Al-Khobar: Tel: 00966-3-8692900 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 00966-3-8691551 AUSTRALIA U.A.E. • Lakemba NSW: ICIS: Ground Floor • Tel: 00971-6-5632623 Fax: 5632624 165-171, Haldon St. PAKISTAN Tel: (61-2) 9758 4040 Fax: 9758 4030 • 50-Lower Mall, Lahore MALAYSIA Tel: 0092-42-7240024 Fax: 7354072 • E&D BOOKS SDN. -

Dry Ablution (Tayammum)

Dry Ablution (Tayammum) Description: A summarized study of Tayammum (dry ablution), its method of performance, permissibility and nullification. By Imam Mufti Published on 12 Mar 2012 - Last modified on 25 Jun 2019 Category: Lessons >Acts of Worship > Prayers Prerequisites · Ablution (Wudoo). Objectives · To learn about tayammum - the substitute for wudoo when water is not available. · To know the situations where tayammum can be performed. · To learn how to perform tayammum. · To know the surfaces which can be used for tayammum. · To learn what nullifies tayammum. Arabic Terms · Wudoo - ablution. · Ghusl - ritual bath. · Sunnah - The word Sunnah has several meanings depending on the area of study however the meaning is generally accepted to be, whatever was reported that the Prophet said, did, or approved. · Tayammum – dry ablution. Introduction Dry Ablution (Tayammum) 1 of 5 www.NewMuslims.com What should you do in the situation where you have to pray salah (ritual prayer), yet neither have no water suitable for making wudoo, nor the time be able to find such water soon enough to pray on time? What if you are sick and either not able to make wudoo, or making wudoo is detrimental to your health. What is the correct procedure in such a case? The answer to these common questions is to perform a “dry” ablution, which is called tayammum. Tayammum consists of using clean soil or dust to wipe your face and hands with the intention of preparing oneself to pray, and, as such, substitutes wudoo in special circumstances. The procedure and basic conditions of making tayammum are mentioned in the Quran and Sunnah. -

WHEN RELIGION and ORGANIZATION CONFLICT by JOHN

WHEN RELIGION AND ORGANIZATION CONFLICT By JOHN LAROSA Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my most humble appreciation to the men and women of this study; without your perceptions of the world, I would not understand my world. I value your time and your honesty. I would also like to thank Dr. Brain Horton for his hard work and patience with me throughout this process. Further appreciation is extended to Dr. Andrew Clark and Dr. Eronini Megwa for their guidance and leadership. To my father and sister who never stopped believing in me even when I stopped believing in myself, I am forever in debt to you and I love you more than anything. Finally, to Bridget Bishop, without your continued optimism I would not be here today, I love you. April 14, 2011 ii ABSTRACT WHEN RELIGION AND ORGANIZATION CONFLICT John LaRosa, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2011 Supervising Professor: Brian Horton After the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the United States became a much different place to live and work for Muslim-Americans. Muslims are one of most discriminated, misunderstood, and feared groups in the US. This qualitative study used survey questionnaires to explore the potential role conflicts in the workplace faced by Muslim- Americans as they navigate their way through a post 9/11 world. In the workplace, Muslim-Americans are very aware of how they are viewed by other Muslims and non- Muslims alike. -

Prayer for Young and New Muslims

Prayer For Young and New Muslims Imam Yahya M. Al-Hussein 2 Prayer For Young and New Muslims By Imam Yahya M. Al-Hussein Published by: The Islamic Foundation of Ireland 163, South Circular Road, Dublin 8, Ireland. Tel. 01-4533242 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.islaminireland.com 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 7 CHAPTER ONE: PREPARATION FOR THE PRAYER–STAGE 1 9 1.1. THE PRE-CONDITIONS OF PRAYER 11 1.2. WUDU -ABLUTION 12 1.3. THINGS THAT BREAK WUDU -ABLUTION 14 CHAPTER TWO : PRAYER – STAGE 1 2.1. NAMES AND RAK'ATS OF PRAYERS 17 2.2. TIMES OF PRAYER 18 2.3. IQAMAH 20 2.4. SHORT SURAS (QUR’ANIC CHAPTERS) FOR PRAYER 21 2.5. AT-TASHAHUD 24 2.6. HOW THE PRAYER IS PERFORMED 25 2.7. HOW THE FIVE DAILY PRAYERS ARE PERFORMED 28 CHAPTER THREE: PREPARATION FOR THE PRAYER – STAGE 2 3.1. TYPES OF WATER 33 3.2. GHUSL 35 3.3. TAYAMMUM 38 3.4. WIPING OVER THE SOCKS 40 3.5. RULES OF THE TOILET ROOM 42 CHAPTER FOUR : PRAYER – STAGE 2 4.1. AS-SALATU 'ALA AN-NABBI 45 4.2. FARD ACTS OF THE PRAYER 46 5 4.3. SUNNAH ACTS OF THE PRAYER 47 4.4. DHIKR AND DU'AS AFTER SALAM (END OF PRAYER) 49 4.5. DISLIKED ACTS DURING THE PRAYER 50 4.6. THINGS THAT BREAK THE PRAYER 51 4.7. FORBIDDEN TIMES FOR PRAYER 52 4.8. THE PRAYER OF A TRAVELLER 54 4.9. SUJUD AS-SAHW (PROSTRATION OF FORGETFULNESS) 57 4.10. -

Islamic Law with the Qur’Ĉn and Sunnah Evidences

Islamic Law with the Qur’Ĉn and Sunnah Evidences (From ٖanafţ Perspective) Dr. Recep Dogan FB PUBLISHING SAN CLEMENTE Copyright © 2013 by Dr. Recep Dogan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including photocopying, recording, and information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, FB Publishing. Published by: FB Publishing 645 Camino De Los Mares Suite 108-276 San Clemente, CA 92673 Visit our website at www.fbpublishinghouse.com Cover design: Cover Design: Gokmen Saban Karci Book Design: Daniel Middleton | www.scribefreelance.com ISBN: 978-0-9857512-4-1 First Edition, July 2013 Published in the United States of America CONTENTS PREFACE ......................................................................................................................... IX TRANSLITERATION TABLE ......................................................................................... xi FIQH ................................................................................................................................ 12 THE LITERAL MEANING OF FIQH ........................................................................... 12 M) ................................................................................... 14 THE LEGAL RULES (AٖK LEGAL CAPACITY (AHLIYAH) IN ISLAMIC LAW ..................................................... 15 M-I SHAR’IYYA) ........................................... -

Concepts of Social Justice: an Islamic Perspective

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol.8, No.4, 2016 Concepts of Social Justice: An Islamic Perspective Shakeel Ahmad Sofi Senior Research Fellow, Department of Management Studies, Central University of Kashmir (J&K) India Dr. Fayaz Ahmad Nika Associate Professor, Department of Management Studies,Central University of Kashmir (J&K) India Abstract Whole world is witnessing turmoil engulfed by an unending conflict and the causes may not be open to general public but it is largely rooted in the race for hegemony. This commotion will prolong till people don’t realize it and don not struggle to destroy the hegemony of evil doctrine. There are many avenues through which this doctrine can challenged and Social Justice is one such aspect which can shape the worldly affairs under one umbrella. But certain things are warranted too and it needs to be ascertained as what will determine Social Justice. The conception of Social justice finds its significance in every blissful society as no individual with human compassion would like to impair others. Different definitions and frameworks have been put forward to establish impartiality and that may govern the state of affairs of a county. But there still exist difficulty in shaping impartiality throughout the world. This paper in an attempt tries to explore the pros and cons of the manmade laws for developing impartiality and then finally outlines the framework proposed by the Almighty Allah, ‘The Lord of Lands”. The researcher has compared rules and penalties instituted by mankind and those revealed in the Book of Allah, “Al-Quran”. -

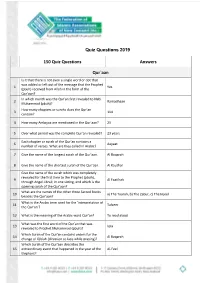

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

The Healthcare Provider's Guide to Islamic Religious Practices

The Healthcare Provider’s Guide to Islamic Religious Practices About CAIR The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) is the largest American Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States. Its mission is to enhance understanding of Islam, protect civil rights, promote justice, and empower American Muslims. CAIR-California is the organization’s largest and oldest chapter, with offices in the Greater Los Angeles Area, the Sacramento Valley, San Diego, and the San Francisco Bay Area. According to demographers, Islam is the world’s second largest faith, with more than 1.6 billion adherents worldwide. It is the fastest-growing religion in the U.S., with one of the most diverse and dynamic communities, representing a variety of ethnic backgrounds, languages, and nationalities. Muslims are adding a new factor in the increasingly diverse character of patients in the health care system. The information in this booklet is designed to assist health care providers in developing policies and procedures aimed at the delivery of culturally competent patient care and to serve as a guide for the accommodation of the sincerely-held religious beliefs of some Muslim patients. It is intended as a general outline of religious practices and beliefs; individual applications of these observances may vary. Disclaimer: The materials contained herein are not intended to, and do not constitute legal advice. Readers should not act on the information provided without seeking professional legal counsel. Neither transmission nor receipt of these materials creates an attorney- client relationship between the author and the receiver. The information contained in this booklet is designed to educate healthcare providers about the sincerely-held and/or religiously mandated practices/beliefs of Muslim patients, which will assist providers in delivering culturally competent and effective patient care. -

Islamic Studies and Religious Education Bi-Annual Curriculum

Islamic Studies and Religious Education bi-annual Curriculum Subject Leader: Mr Abdullah AS Patel, Deputy Head Teacher Intent We are committed to providing a curriculum with breadth that allows all our pupils to be able to achieve the following: ● Build Islamic character, through the termly topics, and a special focus on character building in the final term. ● To learn relevant knowledge to their religious preferences and the values they come with from home. ● To challenges, motivate, inspire and lead them to a lifelong interest in learning, using their Islamic values as a base for further religious exploration, in further education. ● To facilitate pupils to achieve their personal best and grow up to be Muslims with a strong sense of identity. ● To create a link between different subjects to give the pupils and appreciation of the breadth and connected nature of learning. ● To promote active community involvement, we will ensure pupils are prepared for life in modern Britain, by teaching universal human values, and dedicating time in the year to learning specifically about British Values. Implementation To help us achieve our Islamic Studies curriculum intent, we will: ● Offer a quality-assured curriculum using multiple syllabi, and ensuring all lessons are well-planned and effectively delivered. ● Provide pupils and parents with ‘Tarbiyah’ checklists to monitor their character-building progress. ● Where appropriate, we will provide pupils with the tools to learn more effectively by means of practical demonstrations. ● To build a sense of tolerance and respect, we will arrange trips to visit different places of worship to learn about others and appreciate their teachings. -

The Advantages of Wudhu for Some Contemporary Problems

Maddika : Journal of Islamic Family Law Vol. 02, No. 01,September-2020 (E) ISSN : 2775-7161 http://ejournal.iainpalopo.ac.id/index.php/maddika THE ADVANTAGES OF WUDHU FOR SOME CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS 1Adinda Putri Alim, 2Albazar, 3Triya Marselina, 4Zaim Rais Universitas Islam Negeri Imam Bonjol Padang [email protected] Abstract This article aims to discuss the Hadas, (excretion) and najis that are an obstacle for us to perform worship to Allah SWT. Repeating the study of taharah and najis in Islamic Fiqh will make us find a rule and discussion that we have never known before. It is necessary to Clean or clean first to worship to the maximum To get rid of the Hadas, and unclean. Clean signals that we should always clean our souls from sin and all vile deeds. Clean is performed not only to achieve worship but also to maintain the cleanliness and health of the human body. We are required to know all the ins and outs of Clean and practice it correctly. There are still many Muslims who even do not understand Clean. The procedure of Clean has been mentioned in fiqh books in great detail. Always, with the method of content analysis and qualitative approach, the author tries to dig back into something that is rarely touched by fiqh books in general. In the reading of Pustaka, the author obtains the status of animal feces that are halal eaten by the meat; it turns out that the wastes are not unclean according to various sects such as Malikyah and Hanabilah. So far, many people think that the feces of chickens, goats, cows, and other livestock ate are unclean and can cancel Clean.