Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Bondage in Peru

CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Stewart UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES COLLEGE LIBRARV DUKE UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Chinese Bondage IN PERU A History of the Chinese Coolie in Peru, 1849-1874 BY WATT STEWART DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1951 Copyright, 195 i, by the Duke University Press PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE SEEMAN PRINTERY, INC., DURHAM, N. C. ij To JORGE BASADRE Historian Scholar Friend Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesebondageinOOstew FOREWORD THE CENTURY just passed has witnessed a great movement of the sons of China from their huge country to other portions of the globe. Hundreds of thousands have fanned out southwestward, southward, and southeastward into various parts of the Pacific world. Many thousands have moved eastward to Hawaii and be- yond to the mainland of North and South America. Other thousands have been borne to Panama and to Cuba. The movement was in part forced, or at least semi-forced. This movement was the consequence of, and it like- wise entailed, many problems of a social and economic nature, with added political aspects and implications. It was a movement of human beings which, while it has had superficial notice in various works, has not yet been ade- quately investigated. It is important enough to merit a full historical record, particularly as we are now in an era when international understanding is of such extreme mo- ment. The peoples of the world will better understand one another if the antecedents of present conditions are thoroughly and widely known. -

Newsletter of the Latin America and Caribbean Section (IFLA/LAC)

Newsletter of the Latin America and Caribbean Section (IFLA/LAC) Number 64 January- June 2014 IFLA seeks new editor for IFLA Journal Ifla participation at the 10th Session of the Open Group on Sustainable Development Goals IFLA Presidential meeting in Helsinki IFLA in the discussions of the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda IFLA and WIPO Section for Latin America and the Caribbean IFLA/LAC International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. IFLA Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean Library and Information Science Research Institute National Autonomous University of Mexico. Av. Universidad núm. 3000 Ciudad Universitaria C.P. 04510. Ciudad de México. Tel.: +55 55 50 74 61 Fax: +55 56 23 03 37. E-mail: [email protected]. IFLANET: http://www.ifla.org. Blog de IFLA/LAC: http://blogs.ifla.org/lac. Newsletter IFLA/LAC is published in June and December each year by the IFLA Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. It is the leading medium of communication among IFLA regional members. Please share your ideas, experiences, contributions and suggestions with the Regional Office. Newsletter IFLA/LAC Editor: Jaime Ríos Ortega Associated Editor: Sigrid Karin Weiss Dutra Compilation and Copy Desk: Edgar Abraham Alameda Rangel Layout and Design: Carlos Ceballos Sosa Newsletter IFLA/LAC Number 64 (January- June 2014). The online edition is published in June and December each year by the IFLA Regional Office of Latin America and the Caribbean. It is the leading medium of communication among IFLA regional members. ISSN: 1022-9868. It is compiled, edited and produced in UNAM Library and Information Science Research Institute, Mexico. -

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

El Pais Digital

EL PAIS DIGITAL CON EL ARTISTA LUIS CAMNITZER "Aprendí a pensar en Uruguay" Pedro da Cruz LUIS CAMNITZER es artista visual, investigador, docente y crítico. Nació en Lübeck, Alemania, en 1937, y un año más tarde su familia emigró a Uruguay. Estudió en la Escuela de Bellas Artes y la Facultad de Arquitectura. En 1964 se radicó en Estados Unidos. En 1969 ingresó como profesor en la State University of New York, en la que enseñó durante treinta años. En 2007 fue curador pedagógico de la Bienal del Mercosur en Porto Alegre, y en 2008 publicó Didáctica de la liberación. Arte conceptualista latinoamericano. Una serie de sus obras, pertenecientes al acervo de DAROS Latinamerica, son actualmente mostradas en el Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales. TOMA DE CONCIENCIA. -Nacido en Alemania, crecido en Uruguay, activo en Estados Unidos. ¿Cómo percibís las distintas posturas sobre tu origen y pertenencia nacional? -Siempre me extraña que haya una creencia subyacente de que el lugar donde nacés se te mete en la estructura genética y te condiciona. Me parece una posición muy reaccionaria e irreal, anticientífica. -Tú viniste a Uruguay con tu familia cuando tenías un año. -Exacto. Siempre digo que si mis padres hubieran esperado un año, hubiera nacido en Uruguay. ¿Y eso me hace distinto? No. Sería exactamente la misma persona. Entonces, la nacionalidad, en la medida en que crees en que la nacionalidad tiene sentido, o la nación tiene sentido, la ubicas por los entornos culturales. No por los entornos donde respiraste por primera vez, sino donde tomaste conciencia por primera vez. -

Codo Del Pozuzo) Pueblo Nuevo R Codo Del Pozuzo Pueblo Libre Nuevo Dantas John Peter Pueblo Nuevo CODO DEL POZUZO HU HU Santa Ana Emp

76° W 395000 400000 405000 410000 415000 420000 425000 430000 435000 440000 445000 450000 455000 460000 465000 470000 475000 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 R San Gregorio / La Playa í Río Nova San Gregorio Ricardo Herrera o Alto Huayhuante Ricardo Herrera. Río Nova Incari. Santa Seca Juan Velasco. A Río Nova MARISCAL 638 g a Emp. HU-628 ío Nov Nuevo Huayhuante u R 270 CACERES Puerto Libre a y a í t Emp. HU-619 (Dv. Bolaina) t ía y 0 0 HU Pta. Carretera. San Pablo. a u 0 LUYANDO HU 0 628 g BELLAVISTA LORETO A 0 ¬ Alto Huayhuante -Huayhuantillo San Pablo Alto 0 «Supte Chico o 620 í 5 Mishki Punta «¬ Comunidad 5 HU R SAN S S 7 7 Huayhuantillo Nativa ° 619 Heroes del Oriente ° MARTIN UCAYALI 9 9 Supte Chico. Emp. HU-619 (Bolaina). 8 «¬ 8 Bolaina Puerto Azul 8 IRAZOLA HU 8 Bolaina 978 PUENTE LA LIBERTAD Vista Alegre Pta. Carretera (Río Tulumayo). Topa HU «¬ Emp. PE-5N (Galicia) Emp. HU-622 Topa GALICIA TOCACHE Sol Naciente 610 a «¬ e Bajo Guayabal Alto Galicia. San Jorge Galicia t Nueva Union San Miguel de Tulumayo R i PATAZ CORONEL HU Huascar í h Río Negro Emp. HU-619 o N c PORTILLO Julio Cesar Tello o a Emp. HU-622 (Supte San Jorge) 622 Emp. HU-622 va P Supte San Jorge o «¬ Huascar í Atahualpa Emp. HU-622 11 de Octubre R Emp. HU-622 Estación Metereológica Supte. SIHUAS UCAYALI Vista Alegre Atahuallpa Sanja Seca a e POMABAMBA HU t HU i Sanja Seca h San Antonio RUPA-RUPA 624 c 627 a PADRE «¬ P ¬ MARAÑON « Comunidad ABAD 207 o Capitan Arellano. -

2015 Year in Review

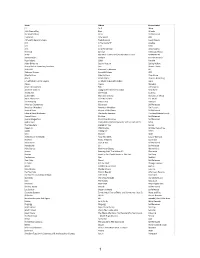

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

GIORGIO MORODER Album Announcement Press Release April

GIORGIO MORODER TO RELEASE BRAND NEW STUDIO ALBUM DÉJÀ VU JUNE 16TH ON RCA RECORDS ! TITLE TRACK “DÉJÀ VU FEAT. SIA” AVAILABLE TODAY, APRIL 17 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “DÉJÀ VU FEATURING SIA” DÉJÀ VU ALBUM PRE-ORDER NOW LIVE (New York- April 17, 2015) Giorgio Moroder, the founder of disco and electronic music trailblazer, will be releasing his first solo album in over 30 years entitled DÉJÀ VU on June 16th on RCA Records. The title track “Déjà vu featuring Sia” is available everywhere today. Click here to listen now! Fans who pre-order the album will receive “Déjà vu feat. Sia” instantly, as well as previously released singles “74 is the New 24” and “Right Here, Right Now featuring Kylie Minogue” instantly. (Click hyperlinks to listen/ watch videos). Album preorder available now at iTunes and Amazon. Giorgio’s long-awaited album DÉJÀ VU features a superstar line up of collaborators including Britney Spears, Sia, Charli XCX, Kylie Minogue, Mikky Ekko, Foxes, Kelis, Marlene, and Matthew Koma. Find below a complete album track listing. Comments Giorgio Moroder: "So excited to release my first album in 30 years; it took quite some time. Who would have known adding the ‘click’ to the 24 track would spawn a musical revolution and inspire generations. As I sit back readily approaching my 75th birthday, I wouldn’t change it for the world. I'm incredibly happy that I got to work with so many great and talented artists on this new record. This is dance music, it’s disco, it’s electronic, it’s here for you. -

Exploring Casma Valley Geographical Kinship: Mapping the Landscape of Identity

EXPLORING CASMA VALLEY GEOGRAPHICAL KINSHIP: MAPPING THE LANDSCAPE OF IDENTITY by Maria Orcherton B.A., National University of Distance Education (UNED), 1995 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIAL WORK UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA March 2012 ©Maria Orcherton, 2012 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87533-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87533-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Evolving Transnational Crime-Terrorism Nexus in Peru and Its Strategic Relevance for the U.S

The Evolving Transnational Crime-Terrorism Nexus in Peru and its Strategic Relevance for the U.S. and the Region BY R. EVAN ELLIS1 n September, 2014, the anti-drug command of the Peruvian National Police, DIRANDRO, seized 7.6 metric tons of cocaine at a factory near the city of Trujillo. A Peruvian family-clan, Iin coordination with Mexican narco-traffickers, was using the facility to insert the cocaine into blocks of coal, to be shipped from the Pacific Coast ports of Callao (Lima) and Paita to Spain and Belgium.2 Experts estimate that Peru now exports more than 200 tons of cocaine per year,3 and by late 2014, the country had replaced Colombia as the world’s number one producer of coca leaves, used to make the drug.4 With its strategic geographic location both on the Pacific coast, and in the middle of South America, Peru is today becoming a narcotrafficking hub for four continents, supplying not only the U.S. and Canada, but also Europe, Russia, and rapidly expanding markets in Brazil, Chile, and Asia. In the multiple narcotics supply chains that originate in Peru, local groups are linked to powerful transnational criminal organizations including the Urabeños in Colombia, the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico, and most recently, the First Capital Command (PCC) in Brazil. Further complicating matters, the narco-supply chains are but one part of an increasingly large and complex illicit economy, including illegal mining, logging, contraband merchandise, and human trafficking, mutually re-enforcing, and fed by the relatively weak bond between the state and local communities. -

Studies in Arts

Center for Open Access in Science Open Journal for Studies in Arts 2019 ● Volume 2 ● Number 2 https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0202 ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 OPEN JOURNAL FOR STUDIES IN ARTS (OJSA) ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html [email protected] Publisher: Center for Open Access in Science (COAS) Belgrade, SERBIA www.centerprode.com [email protected] Editorial Board: Chavdar Popov (PhD) National Academy of Arts, Sofia, BULGARIA Vasileios Bouzas (PhD) University of Western Macedonia, Department of Applied and Visual Arts, Florina, GREECE Rostislava Todorova-Encheva (PhD) Konstantin Preslavski University of Shumen, Faculty of Pedagogy, BULGARIA Orestis Karavas (PhD) University of Peloponnese, School of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Kalamata, GREECE Meri Zornija (PhD) University of Zadar, Department of History of Art, CROATIA Responsible Editor: Goran Pešić Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 35 From Figurative Painting to Painting of Substance – The Concept of an Artist Zdravka Vasileva 45 Spectacular Orientalism: Finding the Human in Puccini’s Turandot Francisca Folch-Couyoumdjian 57 Music and Environment: From Artistic Creation to the Environmental Sensitization and Action – A Circular Model Emmanouil C. Kyriazakos Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4.