Exploring Casma Valley Geographical Kinship: Mapping the Landscape of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 5/04

Follow us on NEWSLETTER FAR HORIZONS ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRIPS Volume 19, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Published Erratically by Far Horizons • P.O. Box 2546 • San Anselmo, CA 94979 USA (800) 552-4575 • (415) 482-8400 • fax (415) 482-8495 • www.farhorizons.com • email: [email protected] FEATURED Dear Travelers, JOURNEYS There is probably no other area on this planet where our understanding of past history is changing so fast as in Cambodia. Many of the discoveries mirror that of another powerful rain forest society, the ancient Maya of Travel with Bob Brier! Mexico and Central America. To understand the similarities of the Khmer Join Bob on one of his four trips – Majesty of Egypt and the Maya, we have confirmed the celebrated Mayanist, Michael D. features private visits to tombs that are closed to the Coe, and the deputy director of the Greater Angkor Project (GAP), Damian public, including the gloriously painted Nefatari’s final Evans, to join us onboard a privately-chartered luxurious river vessel with resting place and the chamber high in the Great only 12 cabins to cruise up the mighty Mekong River from the Vietnam Pyramid. On Oases of Egypt , explore the six verdant spring-fed oases: Siwa, Dakhla, Bahariya, Farafra, delta to the unique environment of Cambodia’s Tonle Sap, the huge lake Karga, and the Fayoum. Or join Undiscovered Egypt that swells to cover one fifth of the country during the monsoons. As we to view areas of Egypt that even savvy tourists do not search for out-of-the-way pagodas and gracefully incised sanctuaries, these see - Alexandria; remote areas of Saqqara to view eminent scholars will enlighten and entertain us with stories of these great some of Egypt’s most isolated and spectacular royal civilizations. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4. -

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial

UNITED NATIONS CER International Convention Distr. GENERAL on the Elimination CERD/C/SR.1083 of all Forms of 13 March 1995 Racial Discrimination Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Forty-sixth session SUMMARY RECORD OF THE 1083rd MEETING Held at the Palais des Nations, Geneva, on Tuesday, 7 March 1995, at 3 p.m. Chairman: Mr. GARVALOV CONTENTS CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS, COMMENTS AND INFORMATION SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 9 OF THE CONVENTION (continued) Eighth, ninth, tenth and eleventh periodic reports of Peru ORGANIZATIONAL AND OTHER MATTERS (continued) This record is subject to correction. Corrections should be submitted in one of the working languages. They should be set forth in a memorandum and also incorporated in a copy of the record. They should be sent within one week of the date of this document to the Official Records Editing Section, room E.4108, Palais des Nations, Geneva. Any corrections to the records of the public meetings of the Committee at this session will be consolidated in a single corrigendum, to be issued shortly after the end of the session. GE.95-15597 (E) CERD/C/SR.1083 page 2 The meeting was called to order at 3.15 p.m. CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS, COMMENTS AND INFORMATION SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 9 OF THE CONVENTION (agenda item 4) (continued) Eighth, ninth, tenth and eleventh periodic reports of Peru (CERD/C/225/Add.3; HRI/CORE/1/Add.43) 1. At the invitation of the Chairman, Mr. Vega Santa-Gadea, Mr. Urrutia, Mr. Chauny, Mr. Rubio-Correa, Mr. -

Weak Rule of Law As the Primary Cause of Lower-Quality Latin American Democracies

ABSTRACT Weak Rule of Law as the Primary Cause of Lower-Quality Latin American Democracies Dacie A. Bradley Director: Victor Hinojosa, Ph.D. Drawing on a deep tradition of rule of law literature, spanning from Aristotle to O’Donnell, this thesis argues that the main problem in modern Latin America is a weak rule of law evidenced by ineffective judicial systems unable to sustain vertical and horizontal accountability. A broad analysis of the necessary characteristics and conditions for democratic rule of law leads to mid-range theory on the application of these characteristics in combination with the unique challenges facing modern day Latin America. A case study of Peru examining crime rates and court systems supports gives evidence to the paramount importance of rule of law and its lack thereof within the state and the region as a whole. This lack of strong rule of law gives rise to a host of other current issues and undermines democratic institutions lowering the quality of democracy. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Victor Hinojosa, Thesis Director, Department of Political Science APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: __________________________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: _____________ WEAK RULE OF LAW AS THE PRIMARY CAUSE OF LOWER-QUALITY, LATIN AMERICAN DEMOCRACIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Dacie A. Bradley Waco, Texas August 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Rule of Law Tradition……………………………………………………...1 Chapter Two: Democratic Rule of Law in Modern Latin America……………………...23 Chapter Three: Crime and the Court Systems of Peru: A Case Study…………………..46 Chapter Four: Concluding Remarks on the Strength of Peruvian Rule of Law…………68 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..76 ii CHAPTER ONE: Rule of Law Tradition Latin America has been undergoing a process of democratization for the past thirty years resulting in a plethora of very different outcomes. -

ICAHM Final Program

FINAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM EL PROGRAMA FINAL DEL CONGRESO WITH PAPER ABTRACTS/CON LOS RESUMENES 27-30 NOVEMBER/NOVIEMBRE, 2012 CUZCO, PERU THANK YOU TO OUR HOSTS GRACIAS A NUESTROS ANFITRIONES UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL SAN ANTONIO ABAD DEL CUSCO 1 Monday, November 26 Inauguración en la Municipalidad del Cuzco Words from: Mayor of Cuzco: Economista Luis Florez García Rector of the National University of Cuzco: Dr. Germán Zecenarro Madueño Drs. Douglas Comer and Willem Willems, Co-Presidents of ICAHM Dr. Alberto Martorell, President of ICOMOS-PERU Musical performance: Sylvia Falcón Welcome Cocktail Party in the Museo Machu Picchu, Casa Concha Words from: Dr. Jean-Jacques Decoster, Director of the Museo Machu Picchu Tuesday, November 27 9:00-10:30 Participants pick up their registration materials at Municipalidad del Cuzco 10:30-12:30 KEYNOTE TALKS LOCATION: MUNICIPALIDAD DEL CUZCO MODERATOR: WILLEM WILLEMS 10:30 Doug Comer (Co-President, ICAHM) 11:00 Fritz Lüth (President, European Association of Archaeologists) 11:30 Ruth Shady (Former President, ICOMOS-Peru) 12:00 Nuria Sanz (UNESCO) (read by Willem Willems) 12:30 -2:30 LUNCH BREAK 2:30-5:15 Management and Policy LOCATION: MUNICIPALIDAD DEL CUZCO MODERATOR: HELAINE SILVERMAN 2:30-2:45 Neale Draper: “Managing Archaeological Heritage in the Pilbara Resources Boom” 2:45-3:00 Elin Dalen: “Cultural and Natural Heritage-A New Policy for World Heritage in Norway” 3:00-3:15 Alejandro Camino Diez Canseco: “Making Heritage sites conservation sustainable: the experience of the Global Heritage Fund” 3:15-3:30 -

The Human Rights Trial of Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori: a Milestone in the Global Struggle Against Impunity Conference Executive Summary

The Human Rights Trial of Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori: A Milestone in the Global Struggle Against Impunity Conference Executive Summary An international symposium Convenors: Jo-Marie Burt, George Mason University and Carlos Rivera Paz, Instituto de Defensa Legal (IDL) Lima, Peru, May 19-20, 2010 With the support of the Latin American Program of the Open Society Institute The Fujimori trial represents a significant milestone in the struggle against impunity and for the consolidation of the rule of law in Peru. But the Fujimori trial transcends the domestic context in important Synopsis ways. George Mason University and the Instituto de Defensa Legal invited renowned international experts to participate in this symposium to reflect on the significance of the Fujimori trial and verdict for anti- impunity efforts in Peru and beyond. Conference Organizers: Conference Co-sponsors: Center for Global Studies The symposium, “The Human Rights Trial of Former President Alberto Fujimori: A Milestone in the Global Struggle against Impunity,” was a collaborative effort organized by George Mason University and the Instituto de Defensa Legal (IDL) to draw local and international attention to the global significance of the Fujimori trial. It was the fifth of a conference series organized by Mason and IDL starting in 2008 with the support of the Latin America Program of the Open Society Institute focusing on the Fujimori trial and the ongoing struggle to combat impunity in Peru and Latin America more broadly. Information about these events, including rapporteur reports and a working paper series, are available at the project website, http://cgs.gmu.edu/HRJDProject.htm. -

Peace and Democratization in Peru: Advances, Setbacks, and Reflections in the 2000 Elections

Peace and Democratization in Peru: Advances, Setbacks, and Reflections in the 2000 Elections A report on a conference sponsored by the George Washington University Andean Seminar and the Washington Office on Latin America Acknowledgements The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and the George Washington University (GWU) Andean Seminar gratefully acknowledge the support of the United States Institute of Peace for this conference, which was held at George Washington University on January 27, 2000. The conference was organized by WOLA Senior Associate Coletta Youngers and GWU Professor Cynthia McClintock. Numerous individuals contributed to the organization of the event, but particular credit goes to WOLA Program Assistant Peter Clark and James Foster of GWU. WOLA research assistant Stephen Moore provided invaluable assistance in transcribing the conference tapes. We would also like to extend our sincere gratitude to all of those who participated in the conference, and in particular those who traveled from Peru. This rapporteur’s report was authored by Cynthia McClintock and edited by Coletta Youngers. It is based on recordings of the presentations and written notes provided by the speakers. In order to release the report in a quick and timely manner, speakers were not provided the opportunity to review the written comments presented in this report. Peter Clark coordinated production and distribution of the report. Introduction On January 27, 2000, historic elections in Peru were just ten weeks away. Nearing the end of almost a decade in office, incumbent President Alberto Fujimori sought an unprecedented third term and led in the polls by a considerable margin. Assessment of the achievements and setbacks to conflict resolution and democracy in Peru during the decade, as well as the prospects for change after the elections, was timely. -

Peru/Chile: Serious Human Rights Violations During the Presidency of Alberto Fujimori (1990- 2000)

What can you do? Help share information about the serious human rights violations committed during the years Alberto Fujimori was president of Peru. Distribute this report as widely as possible amongst friends, contacts, etc. Go to our website : http://www.amnesty.org.uk/action/fujimori.shtml and sign the petition. Thank you. AI Index: AMR 46/007/2005 Amnistía Internacional – December 2005 Amnesty International – December 2005 AI Index: AMR 46/007/2005 Peru/Chile Serious human rights violations during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000) “…It happened around 10pm during a fundraising party, which was to collect donations for improvements to the residence block. Then, at that time, a group of six uniformed people entered abruptly, two were leading and had their faces covered. They started saying things like … miserable terrorists, you are going to get it now … they insulted us and ordered us to lay on the ground. There is the case of Tomás Livias, one of those present, he resisted … and they hit his back and chest with the butts of their rifles and threw him to the ground. One man stood up and said: I’m the one who organized this, do it to me. They shot him. They machined-gunned him and he fell. They went to the right, towards a room where … there were two girls. They went and finished them off with shots, they returned to attack us when we were on the floor. Then the massacre started…”1 This is how survivors of the Barrios Altos massacre recounted their testimony to the Comisión de la Verdad y la Reparación (CVR), Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Peru. -

Place and Nation in the Theatre of Yuyachkani, Bando De Teatro Olodum and Catalinas Sur

Staging Port Cities: Place and Nation in the Theatre of Yuyachkani, Bando de Teatro Olodum and Catalinas Sur Michelle Nicholson Sanz Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen Mary, University of London October 2015 1 Statement of Originality I, Michelle Nicholson Sanz, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 9 October 2015. Details of collaboration and publications: Some parts of section 2.3 (‘Re-routing Afro-Brazilian Identity towards the African Diaspora [Áfricas, Bando de Teatro Olodum, 2007]’) have been published as part of the article: ‘On my mind’s world map, I see an Africa: Bando de Teatro Olodum’s Re- routing of Afro-Brazilian Identity’, Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 19 (2014), Special Issue: ‘New Practice, New Methods, New Voices’, 287–95. -

The Initial Period and Early Horizon: Chavín De Huántar Copyright Bruce Owen 2006

Andean Archaeology and Ethnohistory - Anthro 326: Class 12 The Initial Period and Early Horizon: Chavín de Huántar Copyright Bruce Owen 2006 − Note on dates in Kembel and Rick reading − These are the newest and probably best dates for the IP and EH, based on a better understanding of the site of Chavín − they shift the period boundaries several centuries earlier than previously thought − BUT: the dates they give are all in uncalibrated form − Here they are in calibrated years, rounded to the nearest century: − Initial Period (IP): 2200-1000 cal BC (given as 1800-900 uncal BC) − Early Horizon (EH): 1000-200 cal BC (given as 900-200 uncal BC) − (the two scales happen to almost match around 200 BC) − the discussion here draws heavily on Sylvia Kembel's 2001 Stanford dissertation, which radically revises our view of the Early Horizon and Chavín de Huántar − with lots of information from Richard Burger (1992) − and to a lesser extent on Ivan Ghezzi's recent work dating Chanquillo in the Casma valley − there has been a lot of rethinking going on, and it is not necessarily done yet − Decline on the coast: 1000-700 cal BC: the first part of the Early Horizon − Initial Period U-shaped temples had been built, expanded, and used with only minor overall change in design or (apparently) social context for roughly 1000 years − in some valleys there were several of these centers − by the late Initial Period in the Lurin valley, for example, ten different temple complexes were in use at the same time − each probably serving the people in one small segment -

Estudio Sobre Armas De Guerra Y Caza En El Área Centro-Andina

Arqueología y Sociedad Nº 27, 2014: 297-338 ISSN: 0254-8062 Recibido: enero de 2014 Aceptado: mayo de 2014 ESTUDIO SOBRE ARMAS DE GUERRA Y CAZA EN EL ÁREA CENTRO-ANDINA. DESCRIPCIÓN Y USO DE LAS ARMAS DE ESTOCADA Y DE TAJO Vincent Chamussy Investigador asociado al CNRS – Universidad de París I [email protected] RESUMEN Todos los tipos de armas no fueron utilizados de la misma manera ni en el mismo momento durante la prehistoria del área centro-andina. Las armas arrojadizas servían principalmente para la caza. Las armas de estocada han sido armas de guerra por excelencia y la lucha cuerpo a cuerpo, la forma de combate predilecta. Arma de combate temible, la maza siempre ha simbolizado el poder y el prestigio; asimismo, entre las armas de corte, el hacha se convirtió en el arma de sacrificio conocida como tumi, mientras que el cuchillo se volvió puñal. PALABRAS CLAVE: Andes, armas, guerra, caza, instrumento, símbolo. ABSTRACT All types of weapons were not used in the same way and at the same time during the prehistory of the Cen- tral Andean Area. Throwing weapons have been used mainly for hunting and ritual. Thrusting weapons have been war weapons par excellence, and hand to hand fight the preferred type of fight. Among thrus- ting weapons, the club, although dreadful in action, always symbolized power and prestige, while among cutting weapons, the axe became the tool of sacrifice called tumi, whereas the knife became the dagger. KEYWORDS: Andes, warfare, weapons, hunting, tool, symbol. Las armas ofensivas pueden ser clasificadas en tres categorías: las armas de «estocada», las armas «de corte» —cortantes y afiladas—, así como las armas arrojadizas. -

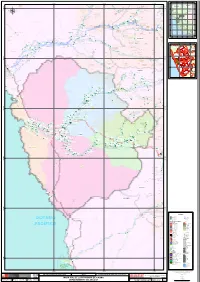

Océano Pacífico

81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W 140000 160000 180000 ° ° 0 0 Socorro Nueva Victoria Comunidad R Santa Domingo ío Rayan COLOMBIA AN C Campesina o Comunidad s Cocate ECUADOR Lampanin Chico 910 m Comunidad 0 Lacramarca «¬La Victoria a Campesina 0 Uchspacancha 0 Campesina 0 Huari Catac Pamparomas 0 Hacienda Condicion Lliclla Alto Karka San Lorenzo de Huata 0 Ticza Chucllash Karcap 0 0 Perque Irca S S AN Comunidad de Cosma Pecu Zanja ° ° 0 Pampa 0 Tambillo 3 3 0 Lliclla Bajo «¬911 Hucapugran / Huaca Punuran 0 Cruz Pampa 9 C. Camp. Cosma Pirurocoto 9 Comunidad Campesina Cosma TUMBES LORETO San Antonio Aoshipu Yepish Anyilirca AN Catorce Incas Marcopampa Colta Jose Carlos Retama 904 Perco Jilca Emp. AN-904 Racratumanca Pacayo a ¬ h Mariategui « c Collique Pucllanca o PIURA AMAZONAS Pampap c Comunidad AN Shiquita a Huaylasquita h c 905 S S o be Campesina «¬ ° ° im Comunidad C G 6 6 o Cosma Alacpampa a LAMBAYEQUE BRASIL í Comunidad Campesina Campesina AN d CAJAMARCA R a 894 r Jose Carlos Pamparomas b µ «¬ e SAN MARTIN Barranco Alto Yanac Alto Peru Mariategui Llacta u ANCASH Cantu Q Llacta Salitre Rupantin Yamahuilca LA LIBERTAD Salitre Grande Chapan Pamparomas Barrio Nuevo Emp. AN-104 S ANCASH S Ulta Emp. AN-104 Catumarca Piedra Grande ° ° Comunidad 9 9 Marco PAMPAROMAS Arenal Nuevo Progreso Lucmash Campesina HUANUCO Sanco Huatas Pampa Carash AN Puquio UCAYALI Canchapampa Tupac Amaru AN 903 PASCO Æ Ä «¬ AN Sectacaca Cochayo Emp. AN-104 Molino 907 Carash Puyapampa 883 Comunidad «¬ Queropuquio «¬ Emp. AN-104 Condorumi Campesina Uchup Cayapo Upianca AN 7 AN Comunidad Campesina PUENTE Comunidad JUNIN S S Chaparral Luis Pardo Emp.