Chapter Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Gilmour HIST480 Dissertation.Pdf

University of Canterbury Propaganda in Prose A Comparative Analysis of Language in British Blue Book Reports on Atrocities and Genocide in Early Twentieth-Century Britain This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of B.A. Honours in History at the University of Canterbury. This dissertation is the result of my own work. Material from the published or unpublished work of other historians used in the dissertation is credited to the author in the footnote references. The dissertation is approximately 9964 words in length. Thomas Gilmour Supervisor: Dr. David Monger Category One HIST480 2016 1 Abstract This paper examines three British Blue Book reports published in early twentieth-century Britain during the war period. The first report examines the invasion of Belgium by the German army and their maltreatment of Belgian people. The second report discusses the Committee of Union and Progress’ acts of cruelty against Armenian Christians. Both of these reports were authored, compiled and then distributed by the British Government in Britain and other Western countries. The third report discusses German colonial rule in South-West Africa and their abuse of ‘native’ Herero. This report was compiled and authored in South- West Africa, but published for a British audience. This dissertation engages in a comparative analysis of these three Blue Book reports. It examines how they are structurally different, but thematically and qualitatively similar. Investigation begins with discussion of the reports’ authors and how they validate claims made in the respective prefaces. Subsequently, there is examination of thematic similarities between each report’s historical narratives. -

Contrasting Portrayals of Women in WW1 British Propaganda

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 of history, propaganda has been aimed at patriarchal Victims or Vital: Contrasting societies and thus, has primarily targeted men. This Portrayals of Women in WWI remained true throughout WWI, where propaganda came into its own as a form of public information and British Propaganda manipulation. However, women were always part of Stacey Reed those societies, and were an increasingly active part History 385 of the conversations about the war. They began to be Fall 2014 targeted by propagandists as well. In war, propaganda served a variety of More than any other war before it, World War I purposes: recruitment of soldiers, encouraging social invaded the every day life of citizens at home. It was the responsibility, advertising government agendas and first large-scale war that employed popular mass media programs, vilifying the enemy and arousing patriotism.5 in the transmission and distribution of information from Various governments throughout WWI found that the the front lines to the Home Front. It was also the first image of someone pointing out of a poster was a very to merit an organized propaganda effort targeted at the effective recruiting tool for soldiers. Posters presented general public by the government.1 The vast majority of British men with both the glory of war and the shame this propaganda was directed at an assumed masculine of shirkers. Women were often placed in the role of audience, but the female population engaged with the encouraging their men to go to war. Many propaganda messages as well. -

Overview Paths of Glory Is a Corps/Army Game Covering All of WWI in Europe and the Near East from August 1914

n June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg crowns of Austria and Hungary, was assassinated by Serb nationalists in Sarajevo, then the capitol of Austrian controlled Bosnia-Herzogovina. The murder of Franz Ferdinand provided an excuse for the Austrian Army's chief of staff, Conrad von Hotzendorff, to "settle accounts" with the upstart Serbs, and on July 23 Austria presented Serbia with an ultimatum with a 48 hour time limit. The Serbs appealed to their traditional protector, Russia, for help. When Russia mobilized, Germany, Austria's ally, declared war on Russia on August 1. Having no plans for a war against Russia alone, Germany soon declared war on Russia's ally, France, and demanded the neutral Belgian government allow German troops passage through Belgium in order to execute the infamous Schlieffen Plan. This demand was refused, and the invasion of Belgium brought Britain into the war against Germany on August 4. In little more than a month the murder at Sarejevo had led to the First World War. Over four years later the war ended on November 11, 1918. The three great dynasties that had begun the war, Habsburg, Romanov, and Hohenzollern, had been destroyed. Lenin was waging a civil war for control of Russia, while Austria-Hungary had dissolved into its various ethnic components. The victors, France and Britain, were in scarcely better shape than the vanquished. The United States of America, which entered the war in April 1917, was disillusioned by the peace that followed and withdrew into isolationism. The Second World War was the result of the First. -

National Narratives of the First World War

NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR AUTHOR(S) Aleksandra Pawliczek COLLABORATOR(S) THEMES World War I PERIOD 1914-2014 Veteran’s of Australia http://www.anzacportal.dva.gov.au/ CENDARI is funded by the European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme for Research 3 CONTENTS 6 NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF 35 THE RAPE OF BELGIUM THE FIRST WORLD WAR – MEMORY AND COMMEMORATION 38 HUNGARY’S LOST TERRITORIES Abstract Introduction 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 THE “GREAT WAR” IN THE UK 12 “LA GRANDE GUERRE” IN FRANCE 16 GERMANY AND WAR GUILT 19 AUSTRIA AND THE END OF THE EMPIRE 21 ANZAC DAY IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA 25 POLAND AND THE WARS AFTER THE WAR 27 REVOLUTIONS AND CIVIL WAR IN RUSSIA 29 SERBIA’S “RED HARVEST” 31 THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE 33 UKRAINE’S FIRST ATTEMPT OF INDEPENDENCE 34 OCCUPATION OF BELARUS 4 5 National Narratives of the First World War – Memory and Commemoration CENDARI Archival Research Guide NATIONAL NARRATIVES OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR – MEMORY Here is not the place to reflect on the ambivalences of public and private memories in AND COMMEMORATION depth (but see also the ARG on Private Memories). It is rather the place to address the strongest current trends and their alteration over time, pointing at the still prevalent nar- ratives in their national contexts, which show huge differences across (European) borders Abstract and manifest themselves in the policy of cultural agents and stakeholders. According to the official memories of the First World War, cultural heritage institutions have varying How is the First World War remembered in different regions and countries? Is there a roles around the Centenary, exposing many different sources and resources on the war “European memory”, a “mémoire partagée”, or do nations and other collective groups and thus also the perceptions of the war in individual countries. -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology. -

Smyrna's Ashes

Smyrna’s Ashes Humanitarianism, Genocide, and the Birth of the Middle East Michelle Tusan Published in association with the University of California Press “Set against one of the most horrible atrocities of the early twentieth century, the ethnic cleansing of Western Anatolia and the burning of the city of Izmir, Smyrna’s Ashes is an important contribution to our understanding of how hu- manitarian thinking shaped British foreign and military policy in the Late Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean. Based on rigorous archival research and scholarship, well written, and compelling, it is a welcome addition to the growing literature on humanitarianism and the history of human rights.” kEitH dAvid wAtEnpAugh, University of California, Davis “Tusan shows vividly and compassionately how Britain’s attempt to build a ‘Near East’ in its own image upon the ruins of the Ottoman Empire served as a prelude to today’s Middle East of nation-states.” pAEtEr M ndlEr, University of Cambridge “Traces an important but neglected strand in the history of British humanitarianism, showing how its efforts to aid Ottoman Christians were inextricably enmeshed in impe- rial and cultural agendas and helped to contribute to the creation of the modern Middle East.” dAnE kEnnEdy, The George Washington University “An original and meticulously researched contribution to our understandings of British imperial, gender, and cultural history. Smyrna’s Ashes demonstrates the long-standing influence of Middle Eastern issues on British self-identification. Tusan’s conclusions will engage scholars in a variety of fields for years to come.” nAncy l. StockdAlE, University of North Texas Today the West tends to understand the Middle East primarily in terms of geopolitics: Islam, oil, and nuclear weapons. -

The Lion, the Rooster, and the Union: National Identity in the Belgian Clandestine Press, 1914-1918

THE LION, THE ROOSTER, AND THE UNION: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE BELGIAN CLANDESTINE PRESS, 1914-1918 by MATTHEW R. DUNN Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for departmental honors Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Andrew Denning _________________________ Dr. Nathan Wood _________________________ Dr. Erik Scott _________________________ Date Abstract Significant research has been conducted on the trials and tribulations of Belgium during the First World War. While amateur historians can often summarize the “Rape of Belgium” and cite nationalism as a cause of the war, few people are aware of the substantial contributions of the Belgian people to the war effort and their significance, especially in the historical context of Belgian nationalism. Relatively few works have been written about the underground press in Belgium during the war, and even fewer of those works are scholarly. The Belgian underground press attempted to unite the country's two major national identities, Flemings and Walloons, using the German occupation as the catalyst to do so. Belgian nationalists were able to momentarily unite the Belgian people to resist their German occupiers by publishing pro-Belgian newspapers and articles. They relied on three pillars of identity—Catholic heritage, loyalty to the Belgian Crown, and anti-German sentiment. While this expansion of Belgian identity dissipated to an extent after WWI, the efforts of the clandestine press still serve as an important framework for the development of national identity today. By examining how the clandestine press convinced members of two separate nations, Flanders and Wallonia, to re-imagine their community to the nation of Belgium, historians can analyze the successful expansion of a nation in a war-time context. -

Living with the Enemy in First World War France

i The experience of occupation in the Nord, 1914– 18 ii Cultural History of Modern War Series editors Ana Carden- Coyne, Peter Gatrell, Max Jones, Penny Summerfield and Bertrand Taithe Already published Carol Acton and Jane Potter Working in a World of Hurt: Trauma and Resilience in the Narratives of Medical Personnel in Warzones Julie Anderson War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: Soul of a Nation Lindsey Dodd French Children under the Allied Bombs, 1940– 45: An Oral History Rachel Duffett The Stomach for Fighting: Food and the Soldiers of the First World War Peter Gatrell and Lyubov Zhvanko (eds) Europe on the Move: Refugees in the Era of the Great War Christine E. Hallett Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War Jo Laycock Imagining Armenia: Orientalism, Ambiguity and Intervention Chris Millington From Victory to Vichy: Veterans in Inter- War France Juliette Pattinson Behind Enemy Lines: Gender, Passing and the Special Operations Executive in the Second World War Chris Pearson Mobilizing Nature: the Environmental History of War and Militarization in Modern France Jeffrey S. Reznick Healing the Nation: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War Jeffrey S. Reznick John Galsworthy and Disabled Soldiers of the Great War: With an Illustrated Selection of His Writings Michael Roper The Secret Battle: Emotional Survival in the Great War Penny Summerfield and Corinna Peniston- Bird Contesting Home Defence: Men, Women and the Home Guard in the Second World War Trudi Tate and Kate Kennedy (eds) -

Historical Analysis of Chemical Warfare in World War I for Understanding the Impact of Science and Technology

Historical Analysis of Chemical Warfare in World War I for Understanding the Impact of Science and Technology An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Cory Houghton John E. Hughes Adam Kaminski Matthew Kaminski Date: 2 March 2019 Report Submitted to: David I. Spanagel Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects ii Acknowledgements Our project team would like to express our appreciation to the following people assisted us with our project: ● Professor David Spanagel, our project advisor, for agreeing to advise our IQP and for helping us throughout the whole process. ● Amy Lawton, Head of the Access Services at Gordon Library, for helping us set up and plan our exhibit at Gordon Library. ● Arthur Carlson, Assistant Director of the Gordon Library, for helping us set up and plan our exhibit as well as helping us with archival research. ● Jake Sullivan, for helping us proofread and edit our main research document. ● Justin Amevor, for helping us to setup and advertise the exhibit. iii Abstract Historians categorize eras of human civilization by the technologies those civilizations possessed, and so science and technology have always been hand in hand with progress and evolution. Our group investigated chemical weapon use in the First World War because we viewed the event as the inevitable result of technology outpacing contemporary understanding. -

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium During the First World War and the Case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives. Ed. Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin and Sophie Kurkdjian. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021. 72–88. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350119895.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 18:11 UTC. Copyright © Selection, editorial matter, Introduction Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards- Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian and Individual chapters their Authors 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture N e l e B e r n h e i m What happens to civil life during wartime is a favorite subject of historians and commands major interest among the learned public. Our best source on the situation in Belgium during the First World War is Sophie De Schaepdrijver’s acclaimed book De Groote Oorlog: Het Koninkrijk Belgi ë tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Th e Great War: Th e Kingdom of Belgium During the Great War). 1 However, to date, there has been no research on the Belgian wartime luxury trade, let alone fashion. For most Belgian historians, fashion during this time of hardship was the last of people’s preoccupations. Of course, fashion historians know better.2 Th e contrast between perception and reality rests on the clich é that survival and subsistence become the overriding concerns during war and that aesthetic life freezes—particularly the most “frivolous” of all aesthetic endeavors, fashion. -

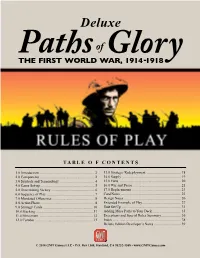

Pog-Deluxe-Rules-FINAL.Pdf

Deluxe TABLE O F CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ............................................................. 2 13.0 Strategic Redeployment ...................................... 18 2.0 Components ............................................................ 2 14.0 Supply ................................................................. 19 3.0 Symbols and Terminology ...................................... 4 15.0 Forts .................................................................... 20 4.0 Game Set-up ............................................................ 5 16.0 War and Peace ..................................................... 21 5.0 Determining Victory ............................................... 6 17.0 Replacements ...................................................... 23 6.0 Sequence of Play ..................................................... 7 Card Notes ................................................................... 23 7.0 Mandated Offensives .............................................. 8 Design Notes ................................................................ 26 8.0 Action Phase ............................................................ 8 Extended Example of Play ........................................... 27 9.0 Strategy Cards ....................................................... 10 Unit Set Up .................................................................. 33 10.0 Stacking ................................................................11 Adding More Paths to Your Deck ...............................