The 1522 Muster Role for West Berkshire (Part 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Compendium of World War Two Memories

World War Two memories Short accounts of the wartime experiences of individual Radley residents and memories of life on the home front in the village Compiled by Christine Wootton Published on the Club website in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War Two Party to celebrate VJ Day in August 1946 Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day) was on 8 August 1945. It's likely the party shown in the photograph above was held in Lower Radley in a field next to the railway line opposite the old village hall. Club member Rita Ford remembers a party held there with the little ones in fancy dress, including Winston Churchill and wife, a soldier and a Spitfire. The photograph fits this description. It's possible the party was one of a series held after 1945 until well into the 1950s to celebrate VE Day and similar events, and so the date of 1946 handwritten on the photograph may indeed be correct. www.radleyhistoryclub.org.uk ABOUT THE PROJECT These accounts prepared by Club member and past chairman, Christine Wootton, have two main sources: • recordings from Radley History Club’s extensive oral history collection • material acquired by Christine during research on other topics. Below Christine explains how the project came about. Some years ago Radley resident, Bill Small, gave a talk at the Radley Retirement Group about his time as a prisoner of war. He was captured in May 1940 at Dunkirk and the 80th anniversary reminded me that I had a transcript of his talk. I felt that it would be good to share his experiences with the wider community and this set me off thinking that it would be useful to record, in an easily accessible form, the wartime experiences of more Radley people. -

The 1522 Muster Role for West Berkshire (Part 5)

Vale and Downland Museum – Local History Series The 1522 Muster Role for West Berkshire (Part 5) - Incomes in Tudor Berkshire: A Recapitulation by Lis Garnish A well reasoned counter argument is always useful in research, calling for a reappraisal of the evidence and possibly opening up new and profitable lines of thought. Having written an initial article in "Oxfordshire Local History" on the 1522 Muster Certificate for west Berkshire (1), and a follow up one suggesting that the figures for “goods” were income rather than capital (2), I was pleased to see Simon Kemp’s article in reply (3). However, I finished reading the item with a sense of disappointment and confusion. Disappointment because he had produced very little in the way of extra evidence from the west Berkshire area, and confusion because he seemed to be countering propositions which I had not made. Kemp's article seems to contain two main lines of argument. Firstly, that the figures for “goods” given in the 1522 Muster Certificate were for “total wealth”, not income, and secondly that the comparison I made with later probate inventories was unjustified. If he had confined himself to the second argument he might have had a valid point. The comparison was a speculative one in an attempt to set the figures in a wider context, although in the absence of other hard evidence I feel it was justifiable to try to draw some conclusions. However, his case for “goods” being capital, as opposed to income, does not seem to have been made. Kemp's first criticism seems to be that two lists were required from the Muster Commissioners, that these were to be separate and that I have ignored this evidence (3). -

River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock

NRA Thames 254 National Rivers Authority Thames Region TR44 River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock Catchment Review October 1994 NRA Thames Region Document for INTERNAL CIRCULATION only National River Authority Thames Region Catchment Planning - West River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock Catchment Review October 1994 River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock - Catchment Review CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE CURRENT STATUS OF THE WATER ENVIRONMENT Overview 2 Geology and Topography 2 Hydrology 2 Water Resources 5 Water Quality 9 Pollution Control 14 Consented Discharges 15 * Flood Defence 18 Fisheries 18 Conservation 19 Landscape 21 Recreation 23 Navigation 26 Land Use Planning Context 29 Minerals 31 P2J73/ i River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock - Catchment Review Page 3. CATCHMENT ISSUES 34 South West Oxfordshire Reservoir Proposal 34 Ground water Pollution 35 River Levels & Flows 35 Habitat Degradation 35 Wolvercote Pit 36 Eutrophication of the Thames 36 River Thames : Seacourt Stream Relationship 36 The River Thames Through Oxford 37 Oxford Structures Study 37 Oxford Sewage Treatment Works 37 Kidlington Sewage Treatment Works 38 Oxford Sewers 38 Development Pressure 38 Navigation Issues 39 Landscape Issues 39 Recreation Issues 39 Wiltshire Berkshire Canal 40 Summary of Key Issues 41 4. CATCHMENT ACTIONS 43 5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 51 P2573/ i i River Thames (Eynsham to Benson) and Ock - Catchment Review LIST OF TABLES Page 2.1 Details of Licensed Ground/Surface Water Abstractions of Greater than lML/day 9 2.2 RQOs, -

Rose Hill-City Centre-Abingdon

Wood Farm - City Centre - Abingdon 4 Mondays to Fridays notes Wood Farm Terminus 69325494 06.10 07.00 08.00 09.06 10.10 11.10 12.10 13.10 14.12 Morrell Avenue Top 69345658 06.19 07.10 08.11 09.16 10.20 11.20 12.20 13.20 14.22 Oxford High Street Queens Lane 69325694 06.26 07.16 08.20 09.25 10.28 11.28 12.28 13.28 14.30 Oxford High Street Carfax 69326483 06.27 07.20 08.23 09.28 10.30 11.30 12.30 13.30 14.32 Oxford Castle Street 69345648 06.30 07.28 08.33 09.38 10.38 11.38 12.38 13.38 14.39 Oxford Frideswide Square 69328972 06.33 07.33 08.38 09.43 10.43 11.43 12.43 13.43 14.43 Botley Elms Parade 69323497 06.38 07.38 08.43 09.48 10.48 11.48 12.48 13.48 14.48 Cumnor Kenilworth Road 69345397 06.46 07.46 08.51 09.56 10.56 11.56 12.56 13.56 14.56 Wootton Sandleigh Road 69327546 06.53 07.53 08.58 10.04 11.04 12.04 13.04 14.04 15.04 Dalton Barracks 69346857 07.02 08.02 09.07 10.13 11.13 12.13 13.13 14.13 15.13 Abingdon High Street 69326827 07.07 08.07 09.12 10.18 11.18 12.18 13.18 14.18 15.18 Abingdon Ock Street - 07.12 08.12 09.17 10.23 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 Wood Farm Terminus 15.18 16.20 17.20 17.50 18.30 19.30 20.30 21.30 22.30 23.15 Morrell Avenue Top 15.28 16.30 17.30 18.00 18.38 19.38 20.38 21.38 22.38 23.23 Oxford High Street Queens Lane 15.36 16.38 17.38 18.08 18.44 19.44 20.44 21.44 22.44 23.29 Oxford High Street Carfax 15.38 16.40 17.40 18.10 18.46 19.46 20.46 21.46 22.46 23.31 Oxford Castle Street 15.46 16.48 17.48 18.18 18.50 19.50 20.50 21.50 22.50 23.35 Oxford Frideswide Square 15.51 16.53 17.53 18.23 18.52 19.52 20.52 21.52 -

Thames Travel 36/X36 from Monday 12 December 2011

Thames Travel 36/X36 From Monday 12 December 2011 Wantage - East Hanney/West Hendred - Didcot Monday to Friday service 36 36 36 36 36 36 X36 X36 X36 X36 X36 Wantage Market Place 06.15 07.2008.20 09.20 10.20 11.20 13.12 14.12 15.12 16.12 17.12 Grove Mayfield Avenue 06.25 07.30 08.30 09.30 10.30 11.30 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ East Hanney Black Horse 06.30 07.3508.35 09.35 10.35 11.35 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Steventon High Street 06.37 07.42 08.42 09.42 10.42 11.42 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Milton Park east 06.41 07.46 08.46 09.46 10.46 11.46 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ West Hendred The Hare ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ 13.17 14.17 15.17 16.17 17.17 Rowstock Corner ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ 13.22 14.22 15.22 16.22 17.22 Harwell Village ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ 13.24 14.24 15.24 16.24 17.24 Didcot Broadway ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.32 17.32 Didcot Orchard Centre ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ 13.33 14.33 15.33 16.33 17.33 Didcot Parkway 06.49 07.54 08.56 09.54 10.54 11.54 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.35 17.35 service X36 X36 X36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 Didcot Parkway 07.54 09.54 10.54 11.54 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.35 17.40 Didcot Orchard Centre 07.56 09.56 10.56 11.56 12.37 13.37 14.37 15.37 16.37 17.42 Didcot Broadway 07.58 09.58 10.58 11.58 12.38 13.38 14.38 15.38 16.38 17.43 Harwell Village 08.03 10.03 11.03 ~~ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Rowstock Corner 08.05 10.05 11.05 ~~ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ West Hendred The Hare 08.10 10.1011.10 ~~ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Milton Park west ↓ ↓ ↓ ~~ 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 16.47 17.52 Steventon High Street ↓ ↓ ↓ ~~ 12.52 13.52 14.52 15.52 16.52 17.57 East Hanney Black Horse ↓ ↓ ↓ ~~ 12.59 13.59 14.59 15.59 16.59 18.04 Grove Mayfield Avenue ↓ ↓ ↓ ~~ 13.03 14.03 15.03 16.03 17.03 18.09 Wantage Market Place 08.17 10.1511.15 ~~ 13.12 14.12 15.12 16.12 17.12 18.18 This service is normally operated with wheelchair accessible buses Thames Travel traveline, Wyndham House Lester Way public transport info: Wallingford 0871 200 22 33 Oxon OX10 9TD Whites Coaches 38 From Monday 12h December 2011 Childrey-Wantage and Wantage Town Service Monday to Saturday MF S Childrey, Village Hall ……………. -

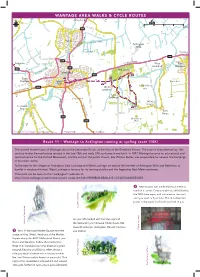

Wantage Area Walks & Cycle Routes

WANTAGE AREA WALKS & CYCLE ROUTES N Abingdon 68 0 1 2 km A338 74 D A O Grove R ED CANAL N DISUS IO T Ardington A F T A S R Wick IN G D O Crab Hill Reading N R O A A417 D A417 OAD DING R Faringdon REA West East Hendred Hendred L A338 A417 NA CA Ardington D SE ISU WANTAGE 4 D A417 East 5 Challow Market 1 Park Hill Square 2 Roundabout B4507 West D ROA Hill TON Lockinge ICKLE 146 East 139 Lockinge D Chain Hill A 132 O C West R H R A Ginge O I N Letcombe N 3 H A I Regis M L L R East O A Ginge D A338 Droveway B4494 Hill 128 Maps produced by Oxford Cartographers, www.oxfordcartographers.com Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 Hungerford Newbury Route 11 – Wantage to Ardington running or cycling route (10K) The ancient market town of Wantage sits on the Letcombe Brook, at the foot of the Berkshire Downs. The town is characterised by 16th century timber framed houses refaced in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in red brick. In 1847 Wantage became an educational and spiritual centre for the Oxford Movement, and the vicar of the parish church, Rev William Butler, was responsible for several fine buildings in the town centre. To the east lie the villages of Ardington, East Lockinge and West Lockinge, as well as the hamlets of Ardington Wick and Betterton (a hamlet in mediaeval times). West Lockinge is famous for its training stables and the legendary Best Mate racehorse. -

Berkshire Parish Registers. Marriages

942.29019 Aalp V.2 1379046 I I GENEALOGY COLLECTIOi \ ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00676 0992 General Editor ... ... T. M. Blagg, F.S.A. BERKSHIRE PARISH REGISTERS fiDarriaoea. PHILLIMORE S PARISH REGISTER SERIES, VOL. CXXXVI. (BERKSHIRE, VOL. One hundred and fifty printed. Berkshire Parish Registers VOL. n. Edited by The lath W. P. W. PHILLIMORE, M.A., B.C.L. AND T. M. BLAGG, F.S.A. HonDon : Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co., Ltd., 124, Chancery Lane, 1914. PREFACE. The present volume has passed through many vicissi- tudes. The MSS. for the first five Parishes were sent to press as long ago as ist July, 1910, by the late Mr. W. P. W. Phillimore, and at his death on 9th April, 1913, it was found that the \'olume was printed off as far as page 96 but that there was not sufficient MS. in hand to complete it. Some time elapsed before the present co-editor, over- whelmed with the labour involved b}' taking over the Chief Editorship of the entire series, now comprising thirtA^ counties, could give attention to completing this volume, and the work in Berkshire has suffered through the lack of an energetic local Editor, such as have come forw^ard in most of the other counties and contributed so greatly to their success. It is hoped that now the Berkshire Series has again been set going, someone interested in the genea- logy of the County will help in this way and so enable this work to be made as useful as in other counties, in many of which the Marriages of over one hundred Parishes have been printed. -

OX12 Health and Care Needs Project Information and Data Pack

OX12 Health and Care Needs Project Information and Data Pack September 2019 . Contents Page Introduction 2 Purpose of the pack 2 OX12 Pack on a page (How to use this document) 4 OX12 Health Profile Summary 5 Population health prevalence across the life course 6 OX12 People and Places 7-9 Housing 9 Housing and Growth 10 Travel and Transport 11-12 Other Factors Affecting Health 13 Health and Care Services 14-21 Appendices 22-28 1 Introduction The partners in the Oxfordshire health and social care system have agreed a new way to planning health, care and wellbeing services using an agreed Health and Care Needs Framework with a population health management (PHM) approach. The first area where the framework has been applied in a specific geographic area is in the OX12 postcode (Wantage, Grove and surrounding villages). Purpose of the pack To co-produce a jargon free overview of the information and data gathered in a way that supports and aids discussions for the OX12 Project. The information and data collection process The ‘health needs’ data has been developed following the metric guidelines in the Public Health England Flatpack for population health management. Work has also been undertaken to map local services and assets and has been supported by an OX12 Project Survey asking local people about the services they currently use and value. Further analysis commissioned provided information on the use of community, mental health and acute based services by patients registered with the two GP practices. Primary Care information has also been analysed and informs this pack. -

Walking in the North Wessex Downs

TRADE PROGRAMME Based on one of the first Great Roads commissioned by the Kings of England, the Great West Way® winds its way through landscapes filled with the world-famous and the yet-to-be-discovered. ParticularlyFIT/self-drive suitable tours for WALKING IN THE NORTH WESSEX DOWNS Give your customers fabulous views hiking on The Ridgeway either on a guided walk or on their own. Used since prehistoric times it is effectively Britain’s oldest road, passing through the glorious North Wessex Downs. Cheltenham BLENHEIM PALACE GREAT WEST WAY Oxford C otswolds ns ROUTE MAP ter hil C e Th Clivedon Clifton Marlow Big Ben Suspension Westonbirt Malmesbury Windsor Paddington Bridge Swindon Castle Henley Castle LONDON Combe Lambourne on Thames wns Eton Dyrham ex Do ess College BRISTOL Park Chippenham W rth Windsor Calne Avebury No Legoland Marlborough Hungerford Reading KEW Brunel’s SS Great Britain Heathrow GARDENS Corsham Bowood Runnymede Ascot Richmond Lacock Racecourse Bristol BATH Newbury ROMAN Devizes Pewsey BATHS Bradford Highclere Cheddar Gorge on Avon Trowbridge Castle Ilford Manor Gardens Westbury STONEHENGE & AVEBURY Longleat WORLD HERITAGE SITE Stourhead Salisbury GREAT WEST WAY GWR DISCOVERER PASS PLACES OF INTEREST INSIDER SUGGESTIONS Journey along the Great West Way on the bus and rail network using the Great West Way GWR Discoverer pass. Includes unlimited Off- Barbury Castle Enjoy classic British pub food at Peak train travel from London Paddington to Bristol via Reading with gastropub Silks on the Downs or White Horse at Uffington options to branch off to Oxford, Kemble and Salisbury via Westbury (or the White Horse Inn, near Calne. -

Transport Issues Assessment

Milton Park - Local Development Order Document: 1 Version: 3 Assessment of Transport Issues 25 September 2012 Milton Park - Local Development Order Document: 1 Version: 3 Assessment of Transport Issues 25 September 2012 Halcrow Group Limited Elms House, 43 Brook Green, London W6 7EF tel +44 20 3479 8000 fax +44 20 3479 8001 halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited is a CH2M HILL company Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of the client, for the client’s sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2012 Document history Milton Park – Local Development Order, Assessment of Transport Issues This document has been issued and amended as follows: Version Date Description Created by Verified by Approved by 00 10/08/2012 Interim draft report JR HS MH 01 03/09/2012 Draft report JR HS MH 01 20/09/2012 Interim revised report JR 02 25/09/2012 Revised report JR HS MH 03 25/09/2012 Revised report HS HS HS Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction 4 2.1 Purpose of Report 4 2.2 Context 4 2.3 Background 5 2.4 Structure of report 6 3 Policy Framework 7 3.1 Introduction 7 3.2 Transport policy 7 3.3 Enterprise Zones and Local Development Orders 14 4 Review of previous transport strategy/assessment work 16 4.1 Introduction 16 4.2 Southern Central Oxfordshire Transport Strategy (SCOTS) 16 4.3 Didcot Area Integrated Transport Strategy & Science Vale UK Area Transport Strategy 17 4.4 DaSTS 18 4.5 Summary of local and strategic measures -

Abingdon 100 Number Status Description Width Conditions + Limitations Remarks (Non-Conclusive Information)

Abingdon 100 Number Status Description Width Conditions + Limitations Remarks (non-conclusive information) 1 FP From Drayton Road at N side of The Poplars, W and S to Diversion Order confirmed 1) Diversion Order Confirmed 4.8.1981. Mill Road at site of Old Canal Bridge. 4.8.81 provided a width 2) Diversion Order Confirmed 19.3.84. of 2m over diverted route. 2 BOAT From New Cut Mill, WSW and SSE to Drayton Parish boundary. 3 FP From Preston Road at Overmead , SW to Borough Part of former FP3 now a maintained boundary at Oday Hill. road. 4 FP From E of Abingdon Lock, E to Culham Parish boundary. 5 FP From Radley Road S for 33m along the E boundary of 1) Diversion Order confirmed 22.10.73 Thomas Read Primary School, then SE and generally provided a width of 6 feet over diverted ENE to the Radley Parish boundary NW of Wick Hall. section. 2) Diversion Order Confirmed (Vale of White Horse (Parishes) Order 1986 transfered 15.1.1986. 3) Vale of White Horse part of Radley FP 8 into Abingdon where it was (Parishes) Order 1986. renumbered as part of Abingdon FP 5). 6 FP From Appleford Drive leading E across Hedgemead Section diverted by Order 1) Diversion Order 14.7.76. 2) Avenue to Radley Road. (Vale of White Horse (Parishes) 22.4.1981(see below) Diversion Order 22.4.81. 3) Vale of Order 1986 transfered all of Radley FP 12 into Abingdon awarded a width of 2m. White Horse (Parishes) Order 1986. where it was renumbered as part of Abingdon FP 6).