Rebuilding Afghanistan's Higher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

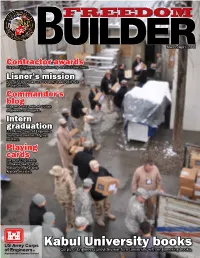

Kabul University Books Corps of Engineers Provides War-Torn University with Engineering Books

March/April 2011 Contractor awards Corps of Engineers recognizes top construction firms. Lisner’s mission N.D. Air Force man serves Army leadership role in Afghanistan. Commander's blog Magness touts role of civilian engineers to bloggers. Intern graduation U.S. Army Corps of Engineers trains and mentors Afghan soldiers. Playing cards Corps of Engineers, Embassy team up to explain the deal with Afghan artifacts. Kabul University books Corps of Engineers provides war-torn university with engineering books. C h Tajikistan in Uz a bekis tan District Commander Col. Thomas Magness AED-North District Command Sergeant Major hshan dak Chief Master Sgt. Forest Lisner Ba Chief of Public Affairs ar J. D. Hardesty uz kh Kund Ta K Layout & Design ash Joseph A. Marek m jan Balkh wz ir Staff Writer Ja Paul Giblin lan Staff Writer gh LaDonna Davis n Ba n ta angan r ta is am e ris n S jsh u e Pan N ar m ul un The Freedom Builder is the field magazine of the Far P K k yab ri n Kapisa n Afghanistan Engineer District, U.S. Army Corps of r a wa L a S ar aghm Engineers; and is an unofficial publication authorized u Bamyan P Kabul by AR 360-1. It is produced monthly for electronic ul ories - r distribution by the Public Affairs Office, U.S. Army T ab St rha K ga Corps of Engineers, Afghanistan Engineer District. It is an produced in the Afghanistan theater of operations. N Views and opinions expressed in The Freedom ardak r Builder are not necessarily those of the Department of n W a dghis g the Army or the U.S. -

OARE Participating Academic Institutions

OARE Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Afghanistan Rehabilitation And Development Center Alfalah University 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Program Afghanistan Centre Cooperation Center For Afghanistan (cca) Ministry of Transport And Civil Aviation Ministry of Urban Development Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Emergency NGO - Afghanistan French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Afghanistan National Public Health Institute, ANPHI Kabul Education University Allied Afghan Rural Development Organization (AARDO) Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Afghan Evaluation Society Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Information and Communication Technology Institute (ICTI) Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan Kabul Medical University Isteqlal Hospital 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan -

Curriculum Vitae

Dr. Homaira Mohammad Azim Apt No. 17, Block No. 54 A, 1st Micro rayon, Kabul, Afghanistan Phone: +93-788-292-331 [email protected] Personal Information Place of Birth: Kabul, Afghanistan Date of Birth: April 25, 1983 Education Attended Be Be Summaya High School in Peshawar, Pakistan Baccalaureate, 1996 Graduated from Kabul Medical University (KMU), Kabul, Afghanistan MD in Medical Sciences, 2007 Non-Formal Education Participated in several training workshops from May 2007 to April 2008. Themes and topics of the trainings included: The Art of Good Rhetoric: Communication, Presentation, and Explanation Skills, Moderation and Facilitation Skills Open Space: a Method for Running and Facilitating Events The Harvard Concept of Negotiation and Conflict Management Leadership for Change: Communication and Leadership Skills Understanding Conflicts and Building Peace with Systemic Conflict Transformation, Phases I & II Youth and Trust Building Language Skills Native Persian speaker Working and studying knowledge of English Knowledge of Pashtu and Urdu Translation skills from English to Persian, Pashtu, and Urdu, and vice versa. 1 Computer Skills Computer programs including MS office, using the web services, some designing soft ware, and soft ware installations Working Experience Anatomy Lecturer at the Kabul Medical University (KMU), K a bu l, Afghanistan, 2008 – pre se nt Conducting lectures on Human Anatomy for the medicine, dentistry, nursing and public health schools at the Kabul Medical University (KMU) Compiling and translating -

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-Standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik ABSTRACT The article aims to introduce a gold-standard Pashto dataset and a segmentation app. The Pashto dataset consists of 300 line images and corresponding Pashto text from three selected books. A line image is simply an image consisting of one text line from a scanned page. To our knowledge, this is one of the first open access datasets which directly maps line images to their corresponding text in the Pashto language. We also introduce the development of a segmentation app using textbox expanding algorithms, a different approach to OCR segmentation. The authors discuss the steps to build a Pashto dataset and develop our unique approach to segmentation. The article starts with the nature of the Pashto alphabet and its unique diacritics which require special considerations for segmentation. Needs for datasets and a few available Pashto datasets are reviewed. Criteria of selection of data sources are discussed and three books were selected by our language specialist from the Afghan Digital Repository. The authors review previous segmentation methods and introduce a new approach to segmentation for Pashto content. The segmentation app and results are discussed to show readers how to adjust variables for different books. Our unique segmentation approach uses an expanding textbox method which performs very well given the nature of the Pashto scripts. The app can also be used for Persian and other languages using the Arabic writing system. The dataset can be used for OCR training, OCR testing, and machine learning applications related to content in Pashto. -

Promoting Female Enrollment in Public Universities of Afghanistan

Promoting Female Enrollment in Public Universities of Afghanistan Higher Education Development Program Ministry of Higher Education Contents 1. Theme 1.1 Increasing Access to priority Degree Programs (Promoting Female Enrollment) .......... 3 2- Kankor Seat Reservation (Special Seats for Female in Priority Desciplines) ..................................... 3 3- Trasnprtaion Services for Female Students ...................................................................................... 4 4- Day Care Services for Female in Public Universities ........................................................................ 5 - KMU………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 - Bamyan…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 - Takhar…………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………….5 - Al-Bironi……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 - Parwan……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….6 5- Counselling Services in Public Univeristies ...................................................................................... 6 - Kabul University - Kabul Education University - Jawzjan University - Bamyan University - Balkh University - Herat University 6- Scholarship (Stipened) for Disadvantaged Female Students ............................................................ 8 7- Female Dorms .................................................................................................................................. 9 2 Theme 1.1: Increasing Access to Priority Degree Programs for Economic Development The objective -

Afghanistan Country Fact Sheet 2018

Country Fact Sheet Afghanistan 2018 Credit: IOM/Matthew Graydon 2014 Disclaimer IOM has carried out the gathering of information with great care. IOM provides information at its best knowledge and in all conscience. Nevertheless, IOM cannot assume to be held accountable for the correctness of the information provided. Furthermore, IOM shall not be liable for any conclusions made or any results, which are drawn from the information provided by IOM. I. CHECKLIST FOR VOLUNTARY RETURN 1. Before the return 2. After the return II. HEALTH CARE 1. General information 2. Medical treatment and medication III. LABOUR MARKET AND EMPLOYMENT 1. General information 2. Ways/assistance to find employment 3. Unemployment assistance 4. Further education and trainings IV. HOUSING 1. General Information 2. Ways/assistance to find accommodation 3. Social grants for housing V. SOCIAL WELFARE 1. General Information 2. Pension system 3. Vulnerable groups VI. EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM 1. General Information 2. Cost, loans and stipends 3. Approval and verification of foreign diplomas VII. CONCRETE SUPPORT FOR RETURNEES 1. Reintegration assistance programs 2. Financial and administrative support 3. Support to start income generating activities VIII. CONTACT INFORMATION AND USEFUL LINKS 1. International, Non-Governmental, Humanitarian Organizations 2. Relevant local authorities 3. Services assisting with the search for jobs, housing, etc. 4. Medical Facilities 5. Other Contacts For further information please visit the information portal on voluntary return and reintegration ReturningfromGermany: 2 https://www.returningfromgermany.de/en/countries/afghanistan I. Checklist for Voluntary Return Insert Photo here Credit: IOM/ 2003 Before the Return After the Return The returnee should The returnee should ✔request documents: e.g. -

INSPIRE the Monthly Employee Newsletter

19th Issue INSPIRE The Monthly Employee Newsletter November 2020 Employee of The Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer Staff Birthdays New Employees Introduction Reflections Birthday Wishes Kardan University wishes a happy birthday to all of our employees who celebrate their birthdays in November. Wahidullah Ibrahimkhail Ahmad Zaki Ludin November 2 November 4 Sarbajeet Mukherjee Faisal Hashimi November 6 November 6 Alauddin Qurishi Jahanzeb Ahmadzai November 8 November 11 Ahmad Khetab Roohullah Hassanyar November 22 November 13 Employee of the Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer We are pleased to announce Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb as our Employee for November 2020. Ms. Tayyeb is an inspiring, committed, and dedicated employee of Kardan University. Ms. Sajida has been immensely cooperative with her students, who are on the verge of graduation to complete their final project. She is handling the online sessions of the department with diligence. Additionally, she has been deeply involved in developing the Departments and the Faculty of Economics' Strategic Plan for the past month. She is also working with the DRD to conduct the upcoming National Conference on SDGs. She is a very dedicated employee, kind teacher, and energetic colleague. The whole department is happy to work by her side We congratulate her on this achievement and wish her the best of luck in her future endeavors. New Employees Introduction Mr. Abdullah Salihy Graphic Designer Mr. Abdullah Salihy joined Kardan University as a Graphic Designer in the Office of Communications. Mr. Salihy holds a bachelor's degree in Fine Arts with a specialization in Graphic Design from Kabul University. -

Afghanistan-Pakistan Activities Quarterly Report XII (July-August-September 2005) Sustainable Development of Drylands Project IALC-UIUC

Afghanistan-Pakistan Activities Quarterly Report XII (July-August-September 2005) Sustainable Development of Drylands Project IALC-UIUC Introduction: Although specific accomplishments will be detailed below, a principal output this quarter was the Scope of Work (SoW) for fiscal year 2006 (FY 06), i.e. October 1, 2005 to September 30, 2006. The narrative portion of the SoW is attached to this report. Readers will note that this submission, which went to IALC headquarters on September 2, presents the progress made by our component thus far and the work ahead of us during year three of the current Cooperative Agreement and year four of the component we have titled “Human Capacity Development for the Agriculture Sector in Afghanistan”. The “Organized Short Courses” section of our FY 06 SoW states our intention to use core funds allocated through the Cooperative Agreement to support four one-month technical courses at an all-inclusive cost of $50,000 per course. As has been done in past years, we were planning to combine core funds with supplemental funds from other sources, allowing us to offer the usual six to eight short courses per year. We were informed by the Project Director that there would be a redistribution of core funds and a reduction in our allocation, from $375,000 in FY 05 to $300,000 this year. If these funds are not restored in full or in part, either from the core or additional Mission buy-in, this budget reduction will add significantly to the challenges we face in FY06 because we will need to generate this short course support from other sources. -

Philanthropy Reflection in Gulpacha "Olfat"

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 Philanthropy Reflection in GulPacha “Olfat” Proses Ehsanullah Pamir1, Khan Muhammad Azizi 2 1Assistant Professor, Paktya University, Language and Literature Faculty, Pashto Department, Gardez, Paktya, Afghanistan 2Assistant Professor, Takhar University, Language and Literature Faculty, Pashto Department, Takhar, Afghanistan Abstract: GulPacha “Olfat” has expressed the issue of the philanthropy in his artistic proses very well, “Olfat” is a star of the Pashto literature, for this reason he can expresses the philanthropy very well. Philanthropy is an origin in this contemporary period, it is philanthropy which it can dissolve the problems of the people, and philanthropy shows the direct and successfulness way for all people. And Allah Says in holy Quran which the all Muslims people are brothers. Different information about the social life has described in “Olfat” proses, and his proses express the social, economic, and political states ,which they have connection with philanthropy and humanity, so all these give very good information for us, and we can find the way of the life by philanthropy. The good way and the successfulness way do exist in the philanthropy, which all they are the inheritance of the GulPacha “Olfat”. So “Olfat” has pointed in his proses to every good way. And also I have decided which I must write anything under the title of the philanthropy, because we must live in the space of affection, and in the space of sympathy. So this topic can give very good counsel for all people, till the people take decision for the making and for progress of their country and society. -

Higher Education Institution Partnership to Strengthen the Health Care Workforce in Afghanistan

http://ijhe.sciedupress.com International Journal of Higher Education Vol. 9, No. 2; 2020 Higher Education Institution Partnership to Strengthen the Health Care Workforce in Afghanistan Carolyn M. Porta1, Erin M. Mann2, Rohina Amiri3, Melissa D. Avery1, Sheba Azim4, Janice M. Conway-Klaassen5, Parvin Golzareh6, Mahdawi Joya7, Emil Ivan Mwikarago8, Mohammad Bashir Nejabi9, Megan Olejniczak10, Raghu Radhakrishnan11, Olive Tengera12, Manuel S. Thomas13, Julia L. Weinkauf10, Stephen M. Wiesner5 1 School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America 2 Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America 3 University Support in Workforce Development Program, Kabul, Afghanistan 4 Anesthesiology Department, Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan 5 Medical Laboratory Sciences Program, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America 6 Midwifery Department, Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan 7 Allied Health Science Department, Medical Lab Technology, Kabul, Afghanistan 8 National Reference Laboratory, Rwanda Biomedical Center, Kigali, Rwanda 9 Department of Prosthodontics, Dentistry Faculty, Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan 10 Department of Anesthesiology, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America 11Office of International Affairs and Collaboration, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, -

·~~~I~Iiiiif~Imlillil~L~Il~Llll~Lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2

·~~~i~IIIIIf~imlillil~l~il~llll~lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2 OPERATION SALAM OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS CO-ORDINATOR FOR HUMANITARIAN AND ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE PROGRAMMES RELATING TO AFGHANISTAN PROGRESS REPORT (JANUARY - APRIL 1990) ACKU GENEVA MAY 1990 Office of the Co-ordinator for United Nation Bureau du Coordonnateur des programmes Humanitarian and Economic Assistance d'assistance humanitaire et economique des Programmes relating to Afghanistan Nations Unies relatifs a I 1\fghanistan Villa La Pelouse. Palais des Nations. 1211 Geneva 10. Switzerland · Telephone : 34 17 37 · Telex : 412909 · Fa·x : 34 73 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................. 5 SECTORAL OVERVIEWS . 7 I) Agriculture . 7 II) Food Aid . 7 Ill) De-m1n1ng . 9 IV) Road repair . 9 V) Shelter . 10 VI) Power . 11 VII) Telecommunications . 11 VI II) Health . 12 IX) Water supply and sanitation . 14 X) Education . 15 XI) Vocational training . 16 XII) Disabled . 18 XIII) Anti-narcotics programme . 19 XIV) Culture . ACKU. 20 'W) Returnees . 21 XVI) Internally Displaced . 22 XVII) Logistics and Communications . 22 PROVINCIAL PROFILES . 25 BADAKHSHAN . 27 BADGHIS ............................................. 33 BAGHLAN .............................................. 39 BALKH ................................................. 43 BAMYAN ............................................... 52 FARAH . 58 FARYAB . 65 GHAZNI ................................................ 70 GHOR ................... ............................. 75 HELMAND ........................................... -

BETWEEN PATRONAGE and REBELLION 1. the 1960S and 1970S

AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Briefing Paper Series Dr Antonio Giustozzi February 2010 BETWEEN PATRONAGE AND REBELLION Student Politics in Afghanistan Contents Introduction 1. The 1960s and Student politics is an important aspect of politics in most countries 1970s ...................1 and its study is important to understanding the origins, development and future of political parties. Student politics is also relevant to elite 2. Post-2001: A different formation, because elites often take their first steps in the political arena environment .......... 4 through student organisations. In Afghanistan today, student politics 3. Post-2001: moves between two poles—patronage and rebellion—and through its Patronage and study we can catch a glimpse of the future of Afghan politics. Careerism ............. 6 Student politics in Afghanistan has not been the object of much 4. Post-2001: Rebellion scholarly attention, but we know that student politics in the 1960-70s Surging................12 had an important influence on the development of political parties, which in turn shaped Afghanistan’s entry into mass politics in the late 5. Conclusion and 1970-80s. The purpose of this study is therefore multiple: to fill a gap Implications ..........15 in the horizon of knowledge, to investigate the significance of changes Annex: Summary of in the student politics of today compared to several decades ago, and Cited Organisations ...16 finally to detect trends that might give us a hint of the Afghan politics of tomorrow. The research is based on approximately 100 interviews About the Author with students and political activists in Kabul, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif and Jalalabad, as well as approximately 12 interviews with former Dr Antonio Giustozzi is student activists of the 1960-70s.