The FCC's Main Studio Rule: Achieving Little for Localism at a Great Cost to Broadcasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

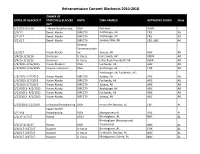

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Appendix a Stations Transitioning on June 12

APPENDIX A STATIONS TRANSITIONING ON JUNE 12 DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LICENSEE 1 ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (D KTXS-TV BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. 2 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC 3 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC 4 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 5 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC 6 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 7 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC 8 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC 9 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 10 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 11 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CW KASY-TV ACME TELEVISION LICENSES OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 12 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM UNIVISION KLUZ-TV ENTRAVISION HOLDINGS, LLC 13 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM PBS KNME-TV REGENTS OF THE UNIV. OF NM & BD.OF EDUC.OF CITY OF ALBUQ.,NM 14 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM ABC KOAT-TV KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. 15 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM NBC KOB-TV KOB-TV, LLC 16 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CBS KRQE LIN OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 17 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM TELEFUTURKTFQ-TV TELEFUTURA ALBUQUERQUE LLC 18 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE CARLSBAD NM ABC KOCT KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. -

2009-332 TTBG Omaha Opco LLC Previously Pappas Telecasting

2009-332 BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS SARPY COUNTY, NEBRASKA RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING CHAIRMAN TO SIGN ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF RECEIPT OF CHANGE IN NOTICE AND PAYMENT INFORMATION REGARDING EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT TOWER LEASE WHEREAS, pursuant to Neb. Rev. Stat. §23-1 04(6) (Reissue 2007), the County has the power to do all acts in relation to the concerns of the county necessary to the exercise of its corporate powers; and, WHEREAS, pursuant to Neb. Rev. Stat. §23-103 (Reissue 2007), the powers ofthe County as a body are exercised by the County Board; and, WHEREAS, Pappas Telecasting ofthe Midlands has assigned all of its rights, duties and obligations under the agreement to lease tower facilities to Sarpy County dated June 7, 1995 to TTBG Omaha 0pC0, LLC, WHEREAS, TTBG Omaha OpCo, LLC has requested that Sarpy County sign an acknowledgment of change in notice provision and change in address to which lease payments are sent to reflect current ownership by TTBG Omaha 0pC0, LLC, NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SARPY COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS THAT, pursuant to the statutory authority set forth above, the Chairman ofthis Board, together with the County Clerk, be and hereby are authorized to sign on behalf of this Board an acknowledgment ofreceipt ofchange in notice and payment information regarding emergency management tower lease, a copy of which is attached hereto. DATED this 3.,d~daof~ember, 2009. ~ Moved by ~,t:h _~ , seconded by ItJYn q:?i~ ,that the above Resolution be adopte . Carried. NAYS: ABSENT: <-/j(ltlJ ABSTAIN: <tl@l Approved as to~ ~Deputy County Attorney TTBG OMAHA OPCO, LLC 4625 Farnam Street Omaha, NE 68132-3222 October 15, 2009 VIA CERTIFIED MAIL - RETURN RECEIPT Emergency Management and Communication Agency Sarpy County Sheriff Sarpy County Courthouse Attn: Larry Lavelle 121 0 Golden Gate Drive Papillion, NE 68046 Re: Notice of Assignment and Assumption of Lease (the "Notice") Lease Agreement, dated 6/7/95, as extended (the "Lease") Dear Mr. -

Sly Fox Buys Big, Gets Back On

17apSRtop25.qxd 4/19/01 5:19 PM Page 59 COVERSTORY Sly Fox buys big, The Top 25 gets back on top Television Groups But biggest station-group would-be Spanish-language network, Azteca America. Rank Network (rank last year) gainers reflect the rapid Meanwhile, Entravision rival Telemundo growth of Spanish-speaking has made just one deal in the past year, cre- audiences across the U.S. ating a duopoly in Los Angeles. But the 1 Fox (2) company moved up several notches on the 2 Viacom (1) By Elizabeth A. Rathbun Top 25 list as Univision swallowed USA. ending the lifting of the FCC’s owner- In the biggest deal of the past year, News 3 Paxson (3) ship cap, the major changes on Corp./Fox Television made plans to take 4 Tribune (4) PBROADCASTING & CABLE’s compila- over Chris-Craft Industries/United Tele- tion of the nation’s Top 25 TV Groups reflect vision, No. 7 on last year’s list. That deal 5 NBC (5) the rapid growth of the Spanish-speaking finally seems to be headed for federal population in the U.S. approval. 6 ABC (6) The list also reflects Industry consolidation But the divestiture 7 Univision (13) the power of the Top 25 doesn’t alter that News Percent of commercial TV stations 8 Gannett (8) groups as whole: They controlled by the top 25 TV groups Corp. returns to the control 44.5% of com- top after buying Chris- 9 Hearst-Argyle (9) mercial TV stations in Craft. This year, News the U.S., up about 7% Corp. -

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER TO: Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER TO: www.cablefax.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 5 Pages Today Thursday — November 30, 2006 Volume 17 / No. 231 ’Tis the Season: EchoStar, Mediacom Fighting Fri Retrans Deadlines There are some things you can count on around this time every year. Turkey leftovers, Santa at the mall… and retrans fights. The latest flare up has Pappas Telecasting threatening to pull all of its broadcast signals from EchoStar on Fri (the same day it has to shutdown all distant network signals) because the 2 have been unable to work out a retrans deal (see story below). Fri is also D-Day for Sinclair and Mediacom’s public retrans spat. On Wed, Mediacom held a confer- ence call to tell its side of the story to city officials and reporters (moments before it began, Sinclair issued a news release headlined, “Sinclair Negotiations With Mediacom Unlikely to Result in an Agreement”). Mediacom hopes the FCC will grant an emergency request to keep the stations on the air. Mediacom chief Rocco Commisso said the MSO upped its offer to Sinclair by 33% over the past week and also agreed to increase its payment by up to 20% if Sinclair inks a deal in the next 2 years exceeding the one it reaches with Mediacom. The MSO also offered Sinclair an a la carte deal in which subs would pay for the broadcast stations if they wanted them. Sinclair rejected the offers, as well as a proposal for bind- ing arbitration, Commisso added. If Mediacom does lose the Sinclair signals at 12:01 Fri, it will impact about 700K subs (50% of its basic subs). -

Broadcast Actions 6/28/2006

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46266 Broadcast Actions 6/28/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/26/2006 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED MI BMLH-20060203ABK WRGZ 49304 WATZ RADIO, INC. License to modify BLED-20051123AHF to change from noncommercial educational to commercial operation. E 96.7 MHZ MI , ROGERS CITY Actions of: 05/30/2006 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED LA BMLED-20060217AAT KYLA 49880 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA License to modify. FOUNDATION E 106.7 MHZ LA , HOMER Actions of: 06/22/2006 TELEVISION APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY DISMISSED MS BPCT-20060317ADW WKDH 83310 SOUTHERN BROADCASTING, Minor change in licensed facilities, callsign WKDH. INC. E CHAN-45 MS , HOUSTON Page 1 of 20 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46266 Broadcast Actions 6/28/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 06/22/2006 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED AL BAL-20060503ABB WEBJ 19823 CANDY CASHMAN SMITH, Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended INDIVIDUAL From: CANDY CASHMAN SMITH, INDIVIDUAL E 1240 KHZ To: BREWTON BROADCASTING, INC. -

08-3078 Document: 003110147203 Page: 1 Date Filed: 05/17/2010

Case: 08-3078 Document: 003110147203 Page: 1 Date Filed: 05/17/2010 Nos. 08-3078, 08-4454, 08-4455, 08-4456, 08-4457, 08-4458, 04-4459, 08-4460, 08-4461, 08-4462, 08-4463, 08-4464, 08-4465, 08-4466, 08-4467, 08-4468, 08- 4469, 08-4470, 08-4471, 04-4472, 08-4473, 08-4474, 08-4475, 08-4476, 08-4477, 08-4478 & 08-4652 In the UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT ___________________________________ PROMETHEUS RADIO PROJECT, et al., Petitioners and Appellants, v. FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondents and Appellee. _________________________________ On Petition for Review and Appeal of an Order of the Federal Communications Commission _________________________________ BRIEF OF APPELLANTS COX ENTERPRISES, INC., COX RADIO, INC., COX BROADCASTING, INC, AND MIAMI VALLEY BROADCASTING CORPORATION AND PETITIONER COX ENTERPRISES, INC. John R. Feore, Jr. Michael D. Hays DOW LOHNES PLLC 1200 New Hampshire Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036-6802 (202) 776-2000 Counsel for Cox Enterprises, Inc.; Cox Radio, Inc.; Cox Broadcasting, Inc.; and Miami Valley Broadcasting Corporation Case: 08-3078 Document: 003110147203 Page: 2 Date Filed: 05/17/2010 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1 and the Rules of this Court, Appellant and Petitioner Cox Enterprises, Inc. and Appellants Cox Radio, Inc., Cox Broadcasting, Inc.1 and Miami Valley Broadcasting Corporation (collectively “Cox”) state as follows: Cox Enterprises, Inc. is a privately held corporation and has no parent companies. Cox Broadcasting, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Cox Holdings, Inc., which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Cox Enterprises, Inc. -

KHAS-TV, Analog Channel 5, Digital Channel 21, NBC KHGI-TV

KHAS-TV, Analog Channel 5, Digital Channel 21, NBC KTVG, Analog Channel 17, Digital Channel 19, FOX Licensee & Group Owner: Greater Nebraska Television, Inc. Licensee: Hill Broadcasting, Inc. 6475 Osborne Drive W., Hastings, NE 68901. Box 220 Kearney, NE 68848. 1078 25th Road, Axtell, NE TEL: (402) 463-1321. FAX: (402) 463-6551. 68848. TEL: (308) 734-2794. FAX: (308) 743-2644. email: [email protected] www.khas.msnbc.com KUON-TV, Analog Channel 12, Digital Channel 40, PBS KHGI-TV, Analog Channel 13, Digital Channel 36, ABC Licensee: University of Nebraska. Licensee: Pappas Telecasting of Central Nebraska, a Box 83111, Lincoln, NE 68501. California, LP. Group Owner: Pappas Telecasting Companies. Street address: 1800 N. Box 220, Kearney, NE 68848-0220. 33rd St., Lincoln, NE 68503. TEL: (402) 472 3611. FAX: (402) 171-8089. Street address: 1078 25th Rd., Axtell, NE www.mynptv.org 68924, GENERAL MANAGER TEL: (308) 743-2494. FAX: (308) 743-2644. www.nebraska.tv Rod Bates V.P. & GENERAL MANAGER Stephen Morris KWNB-TV, Analog Channel 6, Digital Channel 18, ABC PROGRAMMING MANAGER Licensee: Pappas Telecasting of Central Nebraska, a Scott Swenson California, LP. Group Owner: Pappas Telecasting Companies. NEWS DIRECTOR Box 220 Kearney, NE 68848. Mark Baumert Street address: R2, Hayes Center, NE 69032. KHNE-TV, Analog Channel 29, Digital Channel 28, PES TEL: (308) 743 2494. FAX: (308) 743-2644. www.nebraska.tv Licensee: Nebraska Educational Telecommunications NEWS DIRECTOR Commission. Mark Baumert Box 83111, Lincoln, NE 68501. MCCOOK, NE, MARKET Street address: 1800 N. 33rd St., Lincoln, NE 68503. see Wichita - Hutchinson Plus, KS, Market TEL: (402) 472-3611. -

Retransmission-Consent Outlook DIFFICULT and Costly

Retransmission-Consent Outlook DIFFICULT and Costly BY CHRIS CINNAMON, HEIDI SCHMID AND ADRIANA KISSEL n a video world where most operators deliver 150-plus channels, broad- cast stations represent no more than a small slice of channel lineups. Yet the carriage of a few broadcast channels involves a process that for many video providers, especially smaller ones, entails aggravating uncertainty, intense pressure and irrational cost increases. That process? IRetransmission consent. In about 12 months, video providers nationwide will receive certified “election letters” triggering the next round of retransmission-consent negotiations. The out- look for retransmission negotiations in 2011? Difficult and costly. To maximize the likelihood of success—and to minimize pain—preparation is key. Smaller provid- ers should begin preparations now. 32 RURALTELECOM > JULY-AUGUST 2010 ILLUSTRATION BY BRUCE MACPHERSON RTjuly.aug10.FINAL_cc.indd 32 6/18/10 10:07:11 AM RTjuly.aug10.FINAL_cc.indd 33 6/18/10 10:07:12 AM RETRANSMISSION CONSENT WHY NTCA IS CONCERNED About Comcast and NBC Universal By Steve Fravel, NTCA Manager, Video Services Those planning for retransmission-consent negotiations should keep an eye on the Comcast/NBC Universal merger, which could have ramifications for those negotiations. The merger between Comcast, the largest cable provider in the United States, and NBC Universal (NBCU), owner of national television network NBC, creates concern on several levels. Will multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) that compete with Comcast have access to the content cur- rently owned by NBC and Comcast at comparable and competitive terms? The fear is that Comcast will withhold access to “must have” content, or increase the licensing fees to unrealistic levels. -

Station Transactions: 1991 Through September 1998

---Station Transactions: 1991 through September 1998 Page 35 BEAR STEARNS Station Transactions -1991 through September 1998 - In this section, we provide quarterly summaries of significant television transactions that have occurred from 1991 through September 1998. The data summarized include: • the date a transaction was announced (rather than closed) • the property or properties acquired/swapped • the affiliation of the acquired/swapped property • the Designated Market Area (DMA) in which the acquired/swapped television station operates • the purchaser • the seller; and • the purchase price, on the date of announcement. Since the majority of these transactions were private, cash flow and transaction multiple estimates were not available for most of the properties and therefore were not included. These data can be used to determine 1) which broadcasters have been active buyers and sellers; 2) the relative prices paid for different properties in the same market; and 3) relative acquisition activity by quarter. Sources for data in this section: Bear, Stearns & Co. Inc.; Broadcasting & Cable Magazine; Broadcast & Cable Fax; The Wall Street]oumal; The New York Times. BEAR STEARNS Page 36 Q." J T_T_......-~l.. &lifriillOCiklli DOIlii1Iilid IG\CO "'-1Y IIoIbIIntIAno IIl_alllIoI\ 5ep(eri>e<21,1998-- WPGJ(·TV -Fox p"""",ClIy, FL --Woin Broodcas1ing -WIcks_IG~ $7.1_ ~B,I998 WOKR·TV ABC _.NY _,CoorluicaIiono Si1dIir_I~ $125_ 5ep(eri>e< B, 1998 WGME·TV CBS P_,ME SW1cIair_IG""4' Guy GaMoII CoImu1IcoIlono $310_ WlCS-TV NBC ~& Splilgfield-Deca".IL Si1dIirB_IG~ GuyGaMoll~ $310_ Guy _ Cormuicationo WlCD·TV lSimJl;ul) NBC ~ & SpmgfieId-Decalur,IL SW1cIairB_IG~ $310_ Guy _ CoImu1Icollons KGAN·TV CBS CdrRapidS, IA SW1cIairB_IG~ $310_ __IG~ Guy _ CoImu1IcolIons WGGB·TV ABC 5pinglieId,MA $310_ Guy _ CoImu1Icollons WTWC·TV NBC TIIiIaha_.Fl SW1cIairBroadcaItG~ $310_ Guy _ CoImu1Icollons WOKR·TV ABC _,NY SW1cIair_IG~ $310_ $9 _ _ , ComnuicaIion. -

Television Associations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 318 389 IR 014 061 TITLE Satellite Home Viewer Copyright Act. Hearings on H.R. 2848 before the Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Administration of Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (November 19, 1987 and January 27, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. 'louse Committee on the Judiciary. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 751p.; Serial No. 89. Portions contain marginally legible type. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC31 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cable Television; *Communications Satellites; *Copyrights; Federal Legislation; Hearings; *Intellectual Property; *Legal Responsibility; *Policy Formation; Telecommunications IDENTIFIERS Congress 101st ABSTRACT These hearings on the Satellite Home Viewer Copyright Act (H.R. 2849) include:(J.) the text of the bill;(2) prepared statements by expert witnesses (including executives of satellite companies, the Motion Picture Association of Amerira, and cable television associations); (3) transcripts of witneJs testimonies; and (4) additional statements (consisting mostly of letters from telecommunications executives to Congressman Robert W. Kastenmeier) . Appended are legislative materials (Parts 1 and 2 of House of Representatives Report Number 100-887, on the Satellite Home Viewer Copyright Act), additional materials provided by witnesses, and miscellaneous correepondence. ***********A*******************Ak*******************%****************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from fJle original document. ****ft***m*R*******g************************************************w*** SATELLITE HOME VIEWER COPYRIGHT ACT HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COURTS, CIVIL LIBERTIES, AND THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDREDTH CONGRESS FIRST AND SECOND SESSIONS ON H.R. -

Winter 2007-2008 Campaigns on Campus

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA–LINCOLN COJMC ALUMNI MAGAZINE WINTER 2007-2008 CAMPAIGNS ON CAMPUS BREAKING NEWS RENAUD WITNESSES BIRTH OF A KOSOVO NATION I S tory on page 75 NOTEB OOK Ward Jacobson Losing the bridge I’ll never forget the sirens. Coopers of the world had their cameras pointed squarely on the My wife and I had just moved into our southeast Minneapolis rubble, seeking out the people who were there — emergency per- house the previous Thursday. We were about five minutes into din- sonnel, survivors, witnesses. By early the next week, they were all ner on our back patio — a Wednesday evening where the air was gone. heavy, the sky a threatening mix of grey and brown. It was just after Once the last body had finally been recovered, the questions 6 when the sirens started. started coming. Why did this happen? No one wants to hear sirens. Thankfully, they usually last only Then came the data. Some of the numbers were startling as it a few seconds, maybe a minute or two. These sirens seemed to cry was learned just how many bridges in this country were sub-stan- forever. It was Aug. 1. dard. Initially, Minnesotans were reluctant to criticize public offi- As we continued to eat, the sirens grew louder and more per- cials. In this case however, criticism can’t be avoided. sistent. “Must be some wreck on the freeway,” we In the past several weeks I have learned that thought. I-94 is the east-west route connecting transportation concerns in this state have largely Minneapolis and St.