Japanese Shinto Shrine (神社)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reliquaries of Hyrule: a Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time

Press Start The Reliquaries of Hyrule The Reliquaries of Hyrule: A Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time Jared Hansen University of Oregon Abstract This study is a semiotic and iconographic analysis of the sacred architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo, 1998). Through an analysis of the visual elements of the game, the researcher found evidence of visual metaphors that coded three temples as sacred spaces. This coding of the temples is accomplished through the symbolism of progression that matches the design of shrines and cathedrals, drawing on iconography and other symbolism associated with Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sacred architecture. Such indications of sacred spaces highlight the ways in which these virtual environments are designed to symbolize the progression of the player from secular to sacred, much like the player’s progression from zero to hero. By using the architecture and symbolism of the three aforementioned belief systems, Ocarina of Time signifies these temples as reliquaries—that is, sacred places that house reverential items as part of the apotheosis of the player. Keywords Art history; The Legend of Zelda; sacred space; symbolism; temple. Press Start 2021 | Volume 7 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hansen The Reliquaries of Hyrule Introduction The video game experiences that I remember and treasure most are the feelings I have within the virtual environments. -

Old Japan Redux 3

Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG February 2017 The cover painting is a section from 弱竹物語, National Diet Library. Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG, February 2017 Content Poem and Stories The Origins of Japan ……………………………………………… April Grace Petrascu 2 Journal of an Unnamed Samurai ………………………………… Myles Kristalovich 5 Holdout at Yoshino ……………………………………………………… Zachary Adrian 8 Memoirs of Ieyasu ……………………………………………………………… Selena Yu 12 Sword Tales ………………………………………………………………… Adam Cohen 15 Comics Creation of Japan …………………………………………………………… Karla Montilla 19 Yoshitsune & Benkei ………………………………………………………… Alicia Phan 34 The Story of Ashikaga Couple, others …………………… Qianhua Chen, Rui Yan 44 This is a collection of poem, stories and manga comics from the final reports submitted to Japanese Civilization, fall 2016. Please enjoy the young creativity and imagination! P a g e | 2 The Origins of Japan The Mythical History April Grace Petrascu At the beginning Izanagi and Izanami descended The universe was chaos Upon these islands The heavens and earth And began to wander them Just existed side by side Separately, the first time Like a yolk inside an egg When they met again, When heaven rose up Izanami called to him: The kami began to form “How lovely to see Four pairs of beings A man such as yourself here!” After two of genesis The first-time speech was ever used. Creating the shape of earth The male god, upset Izanagi, male That the first use of the tongue Izanami, the female Was used carelessly, Kami divided He once again circled the land By their gender, the only In an attempt to cool down Kami pair to be split so Once they met again, Both of these two gods Izanagi called to her: Emerged from heaven wanting “How lovely to see To build their own thing A woman like yourself here!” Upon the surface of earth The first time their love was matched. -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

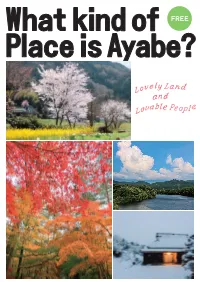

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai. Author: (Katsushika Hokusai) Original Title: (Kanagawa-oki nami ura) Year: 1829 – 1832 Base/stand: Colour-engraved upon a wooden block. Japanese ukiyo-e master. The Great Wave is the most recognized piece by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai, who specializes in ukiyo-e. Published between 1830 and 1833 during the Edo period, it forms part of the collection “Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji”, even though Mount Fuji is the smallest element. The wave references the relentless force of nature, the sea, and the importance this event has in Japan’s economy and its cultural development, given the country is formed by 4 islands. EQUO JUMPTEAM----------FNL-0002RR--_03B 1 Report Created SAT 7 AUG 2021 16 :45 Page 1/7 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Fence 4 – Mascot of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Japanese illustrator Ryo Taniguchi. Manga and gamer references are seen, in representation of the Japanese contemporary visual culture and with a character design inspired by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games’ Logo. The pair of futuristic characters combine tradition and innovation. The name of the Olympics mascot, Miraitowa, fuses the Japanese words for future and eternity. Someity, the Paralympics mascot, is derived from Somei-yoshino, a type of cherry blossom, cherry blossom variety "Someiyoshino" and is a play on words with the English phrase “So mighty”. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Die Riten Des Yoshida Shinto

KAPITEL 5 Die Riten des Yoshida Shinto Das Ritualwesen war das am eifersüchtigsten gehütete Geheimnis des Yoshida Shinto, sein wichtigstes Kapital. Nur Auserwählte durften an Yoshida Riten teilhaben oder gar so weit eingeweiht werden, daß sie selbst in der Lage waren, einen Ritus abzuhalten. Diese zentrale Be- deutung hatten die Riten sicher auch schon für Kanetomos Vorfah- ren. Es ist anzunehmen, daß die Urabe, abgesehen von ihren offizi- ellen priesterlichen Aufgaben, wie sie z.B. in den Engi-shiki festgelegt sind, bereits als ietsukasa bei diversen adeligen Familien private Riten vollzogen, die sie natürlich so weit als möglich geheim halten muß- ten, um ihre priesterliche Monopolstellung halten und erblich weiter- geben zu können. Ein Austausch von geheimen, Glück, Wohlstand oder Schutz vor Krankheiten versprechenden Zeremonien gegen ge- sellschaftliche Anerkennung und materielle Privilegien zwischen den Urabe und der höheren Hofaristokratie fand sicher schon in der späten Heian-Zeit statt, wurde allerdings in der Kamakura Zeit, als das offizielle Hofzeremoniell immer stärker reduziert wurde, für den Bestand der Familie umso notwendiger. Dieser Austausch verlief offenbar über lange Zeit in sehr genau festgelegten Bahnen: Eine Handvoll mächtiger Familien, alle aus dem Stammhaus Fujiwara, dürften die einzigen gewesen sein, die in den Genuß von privaten Urabe-Riten gelangen konnten. Bis weit in die Muromachi-Zeit hin- ein existierte die Spitze der Hofgesellschaft als einziger Orientie- rungspunkt der Priesterfamilie. Mit dem Ōnin-Krieg wurde aber auch diese Grundlage in Frage gestellt, da die Mentoren der Familie selbst zu Bedürftigen wurden. Selbst der große Ichijō Kaneyoshi mußte in dieser Zeit sein Über- leben durch Anbieten seines Wissens und seiner Schriften an mächti- ge Kriegsherren wie z.B. -

Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Teixeira Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric Teixeira, "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon" (2015). Master's Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/626 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON by Eric Teixeira Mendes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Religion Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Stephen Covell, Ph.D., Chair LouAnn Wurst, Ph.D. Brian C. Wilson, Ph.D. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON Eric Teixeira Mendes, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 This thesis offers an examination of modern Japanese amulets, called omamori, distributed by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. As amulets, these objects are meant to be carried by a person at all times in which they wish to receive the benefits that an omamori is said to offer. In modern times, in addition to being a religious object, these amulets have become accessories for cell-phones, bags, purses, and automobiles. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

אמאטרסו أماتيراسو آماتراسو Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amaterasu Amaterasu From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Amaterasu (天照 ), Amaterasu- ōmikami (天照大 神/天照大御神 ) or Ōhirume-no-muchi-no-kami (大日孁貴神 ) is a part of the Japanese myth cycle and also a major deity of the Shinto religion. She is the goddess of the sun, but also of the universe. The name Amaterasu derived from Amateru meaning "shining in heaven." The meaning of her whole name, Amaterasu- ōmikami, is "the great august kami (god) who shines in the heaven". [N 1] Based on the mythological stories in Kojiki and Nihon Shoki , The Sun goddess emerging out of a cave, bringing sunlight the Emperors of Japan are considered to be direct back to the universe descendants of Amaterasu. Look up amaterasu in Wiktionary, the free Contents dictionary. 1 History 2 Worship 3 In popular culture 4 See also 5 Notes 6 References History The oldest tales of Amaterasu come from the ca. 680 AD Kojiki and ca. 720 AD Nihon Shoki , the oldest records of Japanese history. In Japanese mythology, Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, is the sister of Susanoo, the god of storms and the sea, and of Tsukuyomi, the god of the moon. It was written that Amaterasu had painted the landscape with her siblings to create ancient Japan. All three were born from Izanagi, when he was purifying himself after entering Yomi, the underworld, after failing to save Izanami. Amaterasu was born when Izanagi washed out his left eye, Tsukuyomi was born from the washing of the right eye, and Susanoo from the washing of the nose. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work.