Roddy Meagher: a Life in Art Damien Freeman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

41234248.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Trials, Truth-Telling and the Performing Body. Kathryn Lee Leader A thesis submitted to the University of Sydney in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Performance Studies July 2008 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the role performance plays in the adversarial criminal jury trial. The initial motivation behind this inquiry was the pervasiveness of a metaphor: why is the courtroom so frequently compared to a theatre? Most writings on this topic see the courtroom as bearing what might be termed a cosmetic resemblance to a theatre, making comparisons, for instance, between elements of costume and staging. I pursue a different line of argument. I argue that performance is not simply an embellishment of the trial process but rather a constitutive feature of the criminal jury trial. It is by means of what I call the performance of tradition that the trial acquires its social significance as a (supposedly) timeless bulwark of authority and impartiality. In the first three chapters I show that popular usage of the term ‗theatrical‘ (whether it be to describe the practice of a flamboyant lawyer, or a misbehaving defendant) is frequently laden with pejorative connotations and invariably (though usually only implicitly) invokes comparison to a presupposed authentic or natural way of behaviour (‗not-performing‘). Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu I argue that, whatever legal agents see as appropriate trial conduct (behaviour that is ‗not-performing‘), they are misrecognising the performative accomplishments and demands required of both legal agents and laypersons in the trial. -

Harry Crawford V History

Harry Crawford v History: Problem Bodies, Queertrans Cosmogonies, and Historiographical Ethics in Cases of Gender Transgression in Late Nineteenth-Early Twentieth Century Australia Robin Eames 311196152 A treatise submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of: Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Department of History The University of Sydney May 2018 This thesis has not been submitted for examination at this or any other university Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Title page 6 Introduction The historian as cosmographer 7 Trans gravitational waves 9 Finding other universes 10 Chapter one: Problem bodies Gender outlaws: cultural crimes with legal punishments 13 Otherworldly bodies, bodily otherworlds 16 Examining the unmentionables 24 Queer afterlives: listening to the ghosts 29 Chapter two: Queertrans cosmogonies The apparitional trans: hidden from history, haunting the margins 33 The origin of identity: queer myth and metamorphosis 36 The crisis of category 41 Visions and retrovisions 46 Chapter three: Towards a best praxis of transgender historiography Embracing paradox 53 Names have power 54 Queertrans quintessence 59 History Wars Episode IV: A New Hope 68 Coda/Afterthoughts 72 Works cited Epigraphs 74 Primary sources 74 Secondary sources 82 Visual appendix 92 2 Abstract The predominant cultural metanarrative of transgender existence is that we sprang fully formed into being sometime in the 1960s, like Athena stepping out of Zeus’s skull. And yet in every corner of human history we find people who might fit modern definitions of ‘transgender’. This thesis does not seek to retrofit contemporary understandings of gender onto the past. Rather, it sheds light on queertrans antecedence, through the case of Harry Crawford in 1920s Sydney. -

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine Autumn 2007 DIXON THE DEFENDER Reports of the death of our national literature are greatly exaggerated, says the newly appointed chair of Australian literature, ISSN 1834–3937 ISSN Professor Robert Dixon SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine 6 8 20 26 NEWS: BUSINESS SCHOOL ALLIANCE RESEARCH: PREDICTIVE TECHNOLOGY ESSAY: OUR LITERARY CITY SPORT: WOMEN’S CRICKET Autumn 2007 features 10 DIXON THE DEFENDER Reports of Australian literature’s demise are greatly exaggerated. 16 CAMPUS 2027 Editor Dominic O’Grady What kind of world will our students enter The University of Sydney, Publications Office 20 years from now? Room K6.06, Quadrangle A14, NSW 2006 Telephone +61 2 9036 6372 Fax +61 2 9351 6868 Email [email protected] Sub-editor John Warburton regulars Design tania edwards design Contributors Robert Aldrich, Gregory Baldwin, 2LETTERS Tracey Beck, Vice-Chancellor Professor Gavin Brown, Cautious and suspicious: US Studies Centre reaction. Graham Croker, Carole Cusack, Rebecca Johinke, 5 OPINION Stephanie Lee, Robert O'Neill, Peter Reimann, Maggie Renvoize, Chris Rodley, Ted Sealy, Rick Shine, We’ll tolerate complexity for the sake of flexibility, says Vice-Chancellor. Marian Theobald, Geordie Williamson. Printed by PMP Limited. 28 ALUMNI UPDATES Senate approves new name for alumni body. Cover photo Karl Schwerdtfeger. Advertising Please direct all inquiries to the editor. 32 GRAPEVINE Class notes from the 1940s to the present. Editorial Advisory Committee The Sydney Alumni Magazine is supported by an Editorial 36 DIARY Advisory Committee. Its members are: Kathy Bail, Editor, Rational order: Carl Von Linné at the Australian Financial Review Magazine; Martin Hoffman Macleay Museum. -

Mark Tedeschi QC Steps Down As Senior Crown Prosecutor’

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge Gordon Wood Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles On 20 December 2017 Georgina Mitchell and Michaela Whitbourn of the Sydney Morning Herald reported ‘Mark Tedeschi QC steps down as Senior Crown Prosecutor’ The state's top prosecutor, Mark Tedeschi, QC, has announced he will step down in February after two decades in the role. Mr Tedeschi, who was appointed Senior Crown Prosecutor in 1997 after 15 years as a Crown Prosecutor, helped put some of state's most notorious criminals behind bars, including serial killer Ivan Milat and Simon Gittany, who was convicted of throwing his fiancee off a high- rise balcony in Sydney. He was also the prosecutor in three murder trials of Robert Xie - which variously ended in a hung jury, illness of a judge, and the jury being discharged - before Xie was found guilty after a fourth trial. The top prosecutor took an extended period of leave earlier this year and Christopher Maxwell, QC, took over while he was absent. In an email to his colleagues on Wednesday afternoon, Mr Tedeschi said he would now return to being a private barrister. "After a lot of thought and deep consideration, I have decided that in February next year I will return to the Private Bar," Mr Tedeschi said. "I feel that at my age, after 35 years as a Crown Prosecutor including 20 years as Senior Crown Prosecutor, one either should retire or, if one still has the energy to work, reinvent oneself. I have chosen the latter," he said. -

St Patrick's Church Hill, Sydney

Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society Volume 39 2018 Sydney, Central Australia and the West: fields of Catholic endeavour St Patrick’s Church Hill, Sydney 1 Australian Catholic Historical Society Contacts General Correspondence, including membership applications and renewals, should be addressed to The Secretary ACHS PO Box A621 Sydney South, NSW, 1235 Enquiries may also be directed to: [email protected] http://australiancatholichistoricalsociety.com.au/ Executive members of the Society President: Dr John Carmody Vice Presidents: Prof James Franklin Mr Howard Murray Secretary: Ms Helen Scanlon Treasurer: Dr Lesley Hughes ACHS Chaplain: Sr Helen Simpson Cover image: St Patrick’s Church Hill. Sydney Photograph by Gerry Nolan, 31 January 2019 See article page 93 The ACHS meets monthly in the crypt of St Patrick’s 2 Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society JACHS ISSN: 0084-7259 ACHS 2018 soft cover ISBN: 978-1-925872-47-7 ACHS 2018 hard cover ISBN: 978-1-925872-48-4 ACHS 2018 epub ISBN: 978-1-925872-49-1 ACHS 2018 pdf ISBN: 978-1-925872-50-7 Editor: James Franklin Published by ATF Press Publishing Group under its ATF Theology imprint Editorial control and subscriptions remain with the Australian Catholic Historical Society 1 Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society vol 39 2018 Contents Edmund Campion, Archdeacon John McEncroe: An architect of the Australian Church. 4 Colin Fowler, Lewis Harding, catechist at Norfolk Island penal settlement 1838–1842 ..................................... 13 Graeme Pender, The life and contribution of Bishop Charles Henry Davis OSB (1815–1854) to the Catholic Church in Australia .......29 Odhran O’Brien, Beyond Melbourne: Nineteenth-century cathedral building in the Diocese of Perth ............................ -

Wide Open Roads Bullying in the Workplace

JULY–SEPTEMBER 2017 WIDE OPEN ROADS The PSA’s regional organisers BULLYING IN THE WORKPLACE What you can do to make a difference MARK TEDESCHI ...and justice for all PUBLIC SERVICE ASSOCIATION POST OFFICE APPROVED OF NEW SOUTH WALES PP 255003/01563 ISSN 1030-0740 Call us! 13 61 91 OUT with the OLD IN with the NEW Make it happen with an SCU Fixed Rate Car Loan Super low fixed rate Flexible repayment options Fast approval All applications are subject to SCU normal lending criteria. Fees, charges, terms & conditions apply. Sydney Credit Union Ltd ABN 93 087 650 726 I Australian Credit Licence Number 236476 I AFSL 236476. All information is correct as at 20/06/2017 and subject to change. For further information, please call 13 61 91 or visit www.scu.net.au. JULY–SEPTEMBER 2017 CONTENTS News 4 PSA members win a 2.5 per cent pay rise From the General Secretary 10 The fight ahead President’s message 12 Australia’s trade union movement takes stock From the Acting Asst General Secretary 14 The tragedy of privatising Disability Services Member profile 15 Seventeen years at RMS 18 Annual conference 16 A first for the first nations Cover story 18 Mark Tedeschi on the law and unionism Bullying 24 When work goes bad 26 Wide open roads 26 On the beat with the PSA’s regional organisers Your money 31 How to save for a better retirement Our money 32 The PSA’s annual financial statements 24 PUBLIC SERVICE ASSOCIATION OF NEW SOUTH WALES Managing Editor Stewart Little, General Secretary PSA Head Office Issue Editors Murray Engleheart and Jason Mountney A 160 Clarence Street, Sydney NSW GPO Box 3365, Sydney NSW 2001 Art Direction Michael Blythe T 1300 772 679 F (02) 9262 1623 Printers Spotpress, (02) 9549 1111 W www.psa.asn.au E [email protected] www.spotpress.com.au Membership Section Enquiries PSA Communications Unit, 1300 772 679 T 1300 772 679 E [email protected] RED TAPE | 3 NEWS PUGH IN THE FIGHT FOR NORTHERN RIGHTS ASREN Pugh is the PSA’s new regional organiser, working from the soon-to-be- relocated Lismore office. -

Doubt Sydney University Law Society Social Justice Journal 2013 Dissent Doubt Sydney University Law Society Social Justice Journal 2013

issent. DDoubt SYDNEY UNIVERSITY LAW SOCIETY SOCIAL JUSTICE JOURNAL 2013 Dissent Doubt Sydney University Law Society Social Justice Journal 2013 ISSN 1839-1508 Editor-in-Chief Melissa Chen Editorial Board Lucinda Bradshaw Joanna Connolly Nathan Hauser Aden Knaap Nina Newcombe Justin Pen Greta Ulbrick Mala Wadhera Design Judy Zhu Nina Newcombe Melissa Chen Artwork Nina Newcombe With special thanks to Gilbert + Tobin, Sponsor Mark Tedeschi AM QC, Guest Speaker Joellen Riley, Dean James Higgins, SULS Vice-President (Social Justice) Judy Zhu, SULS Design Officer Printing Kopystop Pty Ltd Disclaimer: This journal is published under the auspices of the Sydney University Law Society (SULS). The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors, not the editors. Contents iv Editor-in-Chief’s Foreword v Dean’s Foreword 1 Opening Submission Kate Farrell 2 Doubting DNA Laura Precup-Pop 8 Navigating the Memory Labyrinth Virat Nehru 12 Broken Promises Samuel Murray 17 “That Secret Court Took My Kids Away” Anonymous 25 Doubting Adoption Legislation Dr Catherine Lynch 27 Infamy Jo Seto and Angelica McCall 32 Trial by Media Isabella Kang 36 Trust Me, I’m a Journo David Blight 41 Future or Fad? Catherine Dawson 47 Photographic Essay Raihana Haidary 50 The Plentiful Paradox Connie Ye 57 The Ghost that Keeps on Giving Lewis Hamilton 62 Social Diversity and Social Justice Ellen O’Brien 67 The Privatisation of the Human Genome Christina White 73 Privacy as a Human “Premium” Jo Seto 79 Activism or Slacktivism? John-Ernest Dinamarca 85 Social Justice Snobbery Georgina Meikle 88 Good Intentions James Clifford 93 Closing Submission Kate Farrell 94 Reference List DISSENT iv Editor-in-Chief’s Foreword Doubt confronts us at every turn. -

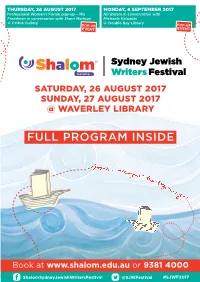

Full Program Inside

THURSDAY, 24 AUGUST 2017 MONDAY, 4 SEPTEMBER 2017 Professional Women’s Forum pop-up – Mia Nir Baram in conversation with Freedman in conversation with Sharri Markson Michaela Kalowski @ COMA Gallery @ Double Bay Library POP-UP POP-UP EVENT EVENT SATURDAY, 26 AUGUST 2017 SUNDAY, 27 AUGUST 2017 @ WAVERLEY LIBRARY FULL PROGRAM INSIDE Book at www.shalom.edu.au or 9381 4000 ShalomSydneyJewishWritersFestival @SJWFestival #SJWF2017 THURSDAY, 24 AUGUST @ COMA GALLERY 7.30 pm - 9.30 pm, COMA Gallery This is a Professional Women’s Forum event, for women only. ‘Work, Strife, Balance’—Mia Freedman in conversation with Sharri Markson POP-UP Meet over wine, cheese and dessert. An honest chat with Mia Freedman. EVENT SATURDAY, 26 AUGUST @ WAVERLEY LIBRARY 7.45 pm - 8.15 pm, MAIN HALL OPENING EVENT Sydney Jewish Writers Festival 2017 — official welcome with music and storytelling from Masha’s Legacy, drinks and dessert, and mingling with our guest authors • 8.30 pm - 10.00 pm, MAIN HALL PANEL • 8.30 pm - 10.00 pm, THEATRETTE DISCUSSION Israel — from the inside and out Megan Goldin, ‘A Boy in Winter’ — in conversation with Alex Ryvchin & Gadi Taub, moderated by Michaela Kalowski Rachel Seiffert with Leah Kaminsky Israel. The word and the place inspire in us all such different extreme Award-winning British author Rachel Seiffert asks the emotions and responses. Whether you sit on the left or the right, no one brave question: how does it feel to be on the wrong can deny that Israel receives more media attention than any other country. side of history? Set in November 1941, A Boy in Winter In this discussion, three very different writers and Israel experts reflect on steers clear of overt descriptions of Nazi horror and the country and writing about it. -

Autumn 2006 History Reports Itself

Autumn 2006 History reports itself Contents Recently, correspondents of the Sydney Morning History of the NSW crown prosecutors............2 Herald shared some jokes about wigs and lawyers. One letter‐writer was blunt, saying that “[a]ny Autumn Quarters...............................................21 barrister will give you 10 spurious reasons why Membership.........................................................22 they retain the wig and gown, and at the same time fail to mention that it makes them feel special, Contact the Forbes Society................................23 while creating an air of superiority over others.”i Another was more cryptic, suggesting that Court as its work was essentially non‐criminal and iv “Australian lawyers wear wigs and gowns so they did not deal with family law cases. will never be confused with quail”.ii A reference to the quail as courtesan, perhaps. Is this recognition, implicit and explicit, of a paradox that while wigs on the one hand are old Given the fact that an overwhelming number of hat in our democratic times, they fulfil or are Australians appear to be able to function without a perceived as fulfilling a role in the areas in which wig, it is likely that there are more reasons the law is and must be the most intrusive? spurious than sensible for its retention by barristers. However, the issue is not without some What will a legal historian in a hundred years complexity. make of all this? Or will it be history? Will wigs in 2106 be regarded as necessary or desirable, In May 1999, Western Australia abolished the wig whatever clobber the barristers – if they still exist – in civil but not criminal matters, with the Chief are wearing? Justice of Western Australia quoted as saying that one of his long‐term goals was to ensure “that the One highly experienced barrister who dons a wig law of the Courts and its procedures are for his criminal work is the Senior Crown Prosecutor for New South Wales, Mark Tedeschi appropriate for the times in which we live”.iii QC. -

M a R K T E D E S C H I

M A R K T E D E S C H I Q C Barrister W A R D E L L C H A M B E R S Level 10, 111 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 DX 379 Sydney T + 61 2 9231 3133 F + 61 2 9233 4164 M + 61 417 279 933 E [email protected] A highly esteemed Queen’s Counsel, Mark possesses over 35 years’ experience prosecuting some of the most complex and high-profile criminal trials in New South Wales. Serving as the Senior Crown Prosecutor – the leader of the State’s Crown Prosecutors – for 20 years, Mark was the Head of Chambers of 80 – 100 Crown Prosecutors and was responsible for their management and for the allocation of all criminal trial briefs. His experience also extended to prosecuting several high-profile political cases overseas. Since joining Wardell Chambers in 2018, Mark has expanded his areas of practice to include both defending and prosecuting criminal matters, disciplinary proceedings, commissions and inquiries, inquests and general regulatory matters, including environmental law prosecutions. He has appeared in a wide range of jurisdictions, including the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court of Australia, and was recently briefed in an Inquiry on behalf of the Government to make recommendations with respect to improvements in efficiency, transparency, fairness and consistency of one of its major departments. His professional interests now also extend to conducting mediations as a mediator. Notably, Mark was appointed a Cavaliere (Italian National Honour) in 2009 and a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2013. -

Swearing in of His Honour Judge J Pickering SC And

COPYRIGHT RESERVED NOTE: Copyright in this transcript is reserved to the Crown. The reproduction, except under authority from the Crown, of the contents of this transcript for any purpose other than the conduct of these proceedings is prohibited. RSB:SND DRAFT IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES THE CHIEF JUDGE THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE D PRICE AM AND THE JUDGES OF THE COURT MONDAY 11 APRIL 2016 SWEARING IN OF HIS HONOUR JOHN PICKERING OF THE DISTRICT COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES SWEARING IN OF HER HONOUR SIOBHAN HERBERT AS A JUDGE OF THE DISTRICT COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES The Honourable G Upton, Attorney General, on behalf of the New South Wales Bar Mr Gary Ulman, President, Law Society of New South Wales, on behalf of solicitors --- (Commission read) (Oaths of office taken) PRICE CJ: Judge Pickering, Judge Herbert, on behalf of all the Judges of this Court, I very warmly welcome you and wish you, each of you, the very best in your judicial careers. JUDGE PICKERING: Thank you, Chief Judge. JUDGE HERBERT: Thank you, Chief Judge. PRICE CJ: Attorney. ATTORNEY GENERAL: Your Honour, it is my privilege today to appear not only as the Attorney General of New South Wales but also on behalf of the New South Wales Bar. We gather today to swear in two outstanding lawyers to the Bench of the District Court of New South Wales. On behalf of the State of New South Wales it is my great pleasure to congratulate his Honour Judge Pickering and her Honour Judge Herbert on your respective appointments. -

FIONA T ROUGHLEY +61 2 9376 0600 Barrister [email protected]

FIONA T ROUGHLEY +61 2 9376 0600 Barrister [email protected] PROFESSIONAL NSW Bar (since 2011). Ranked in: Chambers and Partners, Dispute Resolution (Junior Counsel) (2016 - 2020) Doyle’s Guide to leading junior counsel in commercial litigation and dispute resolution (2015 - 2020); insolvency and restructuring (2018 - 2020), competition (2018, 2019) Principal Research Officer, Department of the Senate, Parliament of Australia (2010). Select Committee on the NBN; Select Committee on the Reform of the Australian Federation; Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs. Associate to the Hon. Justice Hayne AC, High Court of Australia (2009-2010). Allens Arthur Robinson Lawyer (2008 –2009). Competition and Litigation. North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (intern) (Nov 2007 – Feb 2008). Australian Law Reform Commission (intern) (July – Nov 2006). Cambridge University Pro-Bono Project 2010-2011. EDUCATION Australian Institute of Company Directors Graduate, AICD Company Directors Course (2018). The Australian National University PhD candidate (2015-present; part-time). Thesis topic: the role of the Attorney-General for the Commonwealth. Australian Postgraduate Research Training Scholarship. The University of Cambridge Master of Law, Hons Class I (2011). Gates Cambridge Scholarship, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Australian Bicentennial Award for postgraduate study in the UK; Jesus College Foundation Scholarship; first in Course: History and Philosophy of International Law. BANCO.NET.AU The University of Sydney Bachelor of Laws, Hons Class I and the University Medal in Law (2008). Bachelor of Arts, Hons Class I and the University Medal in English (2006). The University of Sydney Convocation Medal (2006) for exceptional contribution to the University and academic excellence.