MPYE – 001 LOGIC Assignment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Infection Control Educational Program an Infection Control Educational Program

AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM By NORICA STEIN RN, BScN A Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Teaching) McMaster University (c) Copyright by Norica Stein, March 1997 MASTER OF SCIENCE (TEACHING) (1997) McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM AUTHOR: Norica Stein RN, B.Sc.N. (McMaster University) SUPERVISORS: Dr. Alice Schutz Professor Muriel Westmorland NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 174 ii ABSTRACT This project describes the development of a curriculum for an infection control liaison program to be implemented in a large, regional health care institution. A curriculum module was designed to both support and challenge practising nurses to utilize critical thinking skills to guide their decision making regarding infection control practices. The author describes the process of curriculum development and presents a final curriculum product. The implementation is presented to demonstrate that the teaching of factual knowledge and skills can be integrated with higher level skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and decision making. Throughout this project, emphasis is placed on educational theory and on the practising health professional as the learner. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With sincere gratitude, I wish to acknowledge the help of my supervisors throughout the completion of my project: Dr. Alice Schutz for encouraging and inspiring me to consider what critical thinking means to me, and Professor Muriel Westmorland who reviewed my project very thoroughly and critically and provided many helpful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to my parents for their encouragement of my pursuit of higher education. -

Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License

Stephen’s Guide to the Logical Fallacies Stephen Downes This site is licensed under Creative Commons By-NC-SA Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License. Based on a work at www.fallacies.ca. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.fallacies.ca/copyrite.htm. This license also applies to full-text downloads from the site. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 How To Use This Guide ............................................................................................................................ 4 Fallacies of Distraction ........................................................................................................................... 44 Logical Operators............................................................................................................................... 45 Proposition ........................................................................................................................................ 46 Truth ................................................................................................................................................. 47 Conjunction ....................................................................................................................................... 48 Truth Table ....................................................................................................................................... -

Biased Argumentation and Critical Thinking

Biased argumentation and critical thinking A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point. Leon Festinger (1956: 3) 1. Introduction Although the problem of biased argumentation is sometimes reduced to the problem of intentional biases (sophistry, propaganda, deceptive persuasion)1, empirical research on human inference shows that people are often biased not because they want to, but because their emotions and interests insidiously affect their reasoning (Kunda 1990, Baron 1988, Gilovich 1991). Walton (forthcoming) highlights this aspect: Many fallacies are committed because the proponent has such strong interests at stake in putting forward a particular argument, or is so fanatically committed to the position advocated by the argument, that she is blind to weaknesses in it that would be apparent to others not so committed. This phenomenon is known as ‘motivated reasoning’ and typically occurs unintentionally, without the arguer’s awareness (Mercier & Sperber 2011: 58, Pohl 2004: 2). For example, a lawyer may be biased in the defense of a client because (s)he deliberately intends to manipulate the audience, to be sure, but also because the desire to win the case (or the sympathy toward the client, etc.) unconsciously distorts the way (s)he reasons and processes the relevant evidence. In such cases, the arguer is sincerely convinced that 1 See for example Herman & Chomsky 1988, Praktanis & Aronson 1991, Walton 2006. 2 Vasco Correia his or her arguments are fair and reasonable, while in fact they are tendentious and fallacious. -

Biases and Fallacies: the Role of Motivated Irrationality in Fallacious Reasoning

COGENCY Vol. 3, N0. 1 (107-126), Winter 2011 ISSN 0718-8285 Biases and fallacies: The role of motivated irrationality in fallacious reasoning Sesgos y falacias: El rol de la irracionalidad motivada en el razonamiento falaz Vasco Correia Institute for the Philosophy of Language New University of Lisbon, Lisboa, Portugal [email protected] Received: 20-12-2010 Accepted: 25-05-2011 Abstract: This paper focuses on the effects of motivational biases on the way people reason and debate in everyday life. Unlike heuristics and cognitive biases, motiva- tional biases are typically caused by the infuence of a desire or an emotion on the cognitive processes involved in judgmental and inferential reasoning. In line with the ‘motivational’ account of irrationality, I argue that these biases are the cause of a number of fallacies that ordinary arguers commit unintentionally, particularly when the commitment to a given viewpoint is very strong. Drawing on recent work in ar- gumentation theory and psychology, I show that there are privileged links between specifc types of biases and specifc types of fallacies. This analysis provides further support to the idea that people’s tendency to arrive at desired conclusions hinges on their ability to construct plausible justifcations for those conclusions. I suggest that this effort to rationalize biased views is the reason why unintentional fallacies tend to be persuasive. Keywords: Argumentation, biases, confrmation bias, fallacies, hasty generalization. Resumen: Este artículo se centra en los efectos de los sesgos motivacionales a partir de la forma en que la gente razona y debate cada día en la vida cotidiana. -

Promoting Translational Research in Medicine Through Deliberation

Promoting Translational Research in Medicine through Deliberation Gordon R. Mitchell and Kathleen M. McTigue• Paper presented at the “Justification, Reason, and Action" Conference in Honor of Professor David Zarefsky Northwestern University Evanston, IL May 29 & 30, 2009 • Gordon R. Mitchell is Associate Professor of Communication and Director of the William Pitt Debating Union at the University of Pittsburgh. Kathleen M. McTigue is Assistant Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology University of Pittsburgh. Portions of this research were presented earlier at the 12th Wake Forest Argumentation Conference in Venice, Italy, June 16‐18, 2008. Promoting Translational Research in Medicine through Deliberation Abstract With the project of drawing upon principles and conceptual tools from argumentation theory to inform the maturing Evidence‐Based Medicine (EBM) movement well underway, the time is ripe to consider the potential of deliberation to elucidate research pathways in translational medicine. While many "benchtop‐to‐bedside" research pathways have been developed in "Type I" translational medicine, vehicles to facilitate "Type II" translation that convert scientific data into clinical and community interventions designed to improve the health of human populations have received less attention. As these latter forms of translational medicine implicate social, political, economic and cultural factors, they require "integrative" research strategies that blend insights from multiple fields of study. This essay considers how argumentation theory's epistemological flexibility, audience attentiveness, and heuristic qualities yield conceptual tools and principles with potential to foster inter‐disciplinary exchange, help research teams percolate cogent arguments, and cultivate physician‐ citizenship, thereby promoting Type II translational medicine. KEYWORDS: translational research, argumentation, rhetoric, Isocrates, hypothesis‐testing, evidence‐based medicine, EBM, public health. -

PAR Syllabus

Philosophy & Reason Senior Syllabus 2004 Philosophy & Reason Senior Syllabus © The State of Queensland (Queensland Studies Authority) 2004 Copyright protects this work. Please read the Copyright notice at the end of this work. Queensland Studies Authority, PO Box 307, Spring Hill, Queensland 4004, Australia Phone: (07) 3864 0299 Fax: (07) 3221 2553 Email: [email protected] Website: www.qsa.qld.edu.au job 1544 CONTENTS 1 RATIONALE ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2 GLOBAL AIMS.................................................................................................................................. 3 3 GENERAL OBJECTIVES.................................................................................................................. 4 3.1 Knowledge:............................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Application ............................................................................................................................. 4 3.3 Communication ...................................................................................................................... 4 3.4 Affective................................................................................................................................. 4 4 COURSE ORGANISATION ............................................................................................................. -

Thinking Logically: Learning to Recognize Logical Fallacies Created by Samantha Hedges and Joe Metzka

Thinking Logically: Learning to Recognize Logical Fallacies Created by Samantha Hedges and Joe Metzka Arguments are presented to persuade someone of a particular view. Credible evidence is an important component of informed, persuasive arguments. When credible evidence is not available, the one presenting the argument often defaults to using other devices to sway thinking, such as logical fallacies. Logical fallacies are common errors in reasoning that undermine the logic of an argument. Fallacies can be illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim. Students need to be aware of these fallacies to present their own viewpoints and engage in open inquiry effectively. One must avoid making fallacious arguments and identify fallacious arguments presented by others to productively engage in open inquiry and constructively disagree with the perspective. This resource outlines common logical fallacies that students may have experienced in their own interactions or those in their social networks. Towards the bottom of the resource, there is a list of additional logical fallacies that students can research and suggestions for activities that can be adapted for high school or college students. Common Logical Fallacies Ad Hominem Ad Hominem means “against the man”. Ad Hominem is when you attack the personal characteristics of the person you’re debating instead of attacking the argument the person is making. In political debates, this is known as “mudslinging”. Example: Candidate 1: “I’m for raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour.” Candidate 2: “You’re for raising the minimum wage, but you’re not even smart enough to run a business.” Candidate 2 attacked the intelligence of Candidate 1 rather than the merits of the minimum wage policy proposed. -

Deconstructing Climate Science Denial

Cite as: Cook, J. (2020). Deconstructing Climate Science Denial. In Holmes, D. & Richardson, L. M. (Eds.) Edward Elgar Research Handbook in Communicating Climate Change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Deconstructing Climate Science Denial John Cook Introduction Numerous studies have found overwhelming scientific consensus on human-caused global warming both in the scientific community (Anderegg et al., 2010; Carlton et al., 2015; Doran & Zimmerman, 2009) and in the scientific literature (Cook et al., 2013; Oreskes, 2004). Conversely, a small minority of climate scientists reject the consensus position, and climate denial has a vanishingly small presence in the scientific literature. The small number of published studies that reject mainstream climate science have been shown to possess fatal errors. Abraham et al. (2014) summarized how papers containing denialist claims, such as claims of cooling in satellite measurements or estimates of low climate sensitivity, have been robustly refuted in the scientific literature. Similarly, Benestad et al. (2016) attempted to replicate findings in contrarian papers and found a number of flaws such as inappropriate statistical methods, false dichotomies, and conclusions based on misconceived physics. Given their lack of impact in the scientific literature, contrarians instead argue their case directly to the public. Denialist scientists self-report a higher degree of media exposure relative to mainstream scientists (Verheggen et al., 2014), and content analysis of digital and print media articles confirms that contrarians have a higher presence in media coverage of climate change relative to expert scientists (Petersen, Vincent, & Westerling, 2019). The viewpoints of contrarian scientists are also amplified by organizations such as conservative think-tanks, the fossil fuel industry, and mainstream media outlets (organizations that generate and amplify climate change denial are examined further in Chapter 4 by Brulle & Dunlap). -

Public Submission

CPS2020-0532 Attach 6 Letter 1 Public Submission City Clerk's Office Please use this form to send your comments relating to matters, or other Council and Committee matters, to the City Clerk’s Office. In accordance with sections 43 through 45 of Procedure Bylaw 35M2017, as amended. The information provided may be included in written record for Council and Council Committee meetings which are publicly available through www.calgary.ca/ph. Comments that are disrespectful or do not contain required information may not be included. FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND PROTECTION OF PRIVACY ACT Personal information provided in submissions relating to Matters before Council or Council Committees is col- lected under the authority of Bylaw 35M2017 and Section 33(c) of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIP) Act of Alberta, and/or the Municipal Government Act (MGA) Section 636, for the purpose of receiving public participation in municipal decision-making. Your name, contact information and comments will be made publicly available in the Council Agenda. If you have questions regarding the collection and use of your personal information, please contact City Clerk’s Legislative Coor- dinator at 403-268-5861, or City Clerk’s Office, 700 Macleod Trail S.E., P.O Box 2100, Postal Station ‘M’ 8007, Calgary, Alberta, T2P 2M5. ✔ * I have read and understand that my name, contact information and comments will be made publicly available in the Council Agenda. * First name Daniel * Last name Komori Email [email protected] Phone * Subject Reworded Definition for Calgary Conversion Therapy Bylaw a group of people in Calgary who are concerned about this bylaw who have gathered under the name "Free to Care" * Comments - please refrain from www.freetocare.ca providing personal information in this field (maximum 2500 They have drafted a version of this bylaw which would protect the rights of individuals characters) from harm, while also respecting the rights of individuals to choose the type of support they want. -

Unit 1 – an Introduction to Proof Through Euclidean Geometry Mga4u0 Unit 1 – an Introduction to Proof Through Euclidean Geometry

MGA4U0 UNIT 1 – AN INTRODUCTION TO PROOF THROUGH EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY MGA4U0 UNIT 1 – AN INTRODUCTION TO PROOF THROUGH EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY..............................................1 WHAT IS A PROOF? – INDUCTIVE AND DEDUCTIVE REASONING .......................................................................................4 NOLFI’S INTUITIVE DEFINITION OF “PROOF” .........................................................................................................................................4 PYTHAGOREAN THEOREM EXAMPLE .....................................................................................................................................................4 Proof: ...............................................................................................................................................................................................4 RESEARCH EXERCISES ...........................................................................................................................................................................4 THE MEANING OF Π – AN EXAMPLE OF DEDUCTIVE REASONING ..........................................................................................................5 Examples ..........................................................................................................................................................................................5 TIPS ON BECOMING A POWERFUL “PROVER”..........................................................................................................................................6 -

Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies

Stephen’s Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes Overview The point of an argument is to give reasons in support of some conclusion. An argument commits a fallacy when the reasons offered do not, in fact, support the conclusion. Each fallacy is described in the following format: Name: this is the generally accepted name of the fallacy Definition: the fallacy is defined Examples: examples of the fallacy are given Proof: the steps needed to prove that the fallacy is committed Note: Please keep in mind that this is a work in progress, and therefore should not be thought of as complete in any way. Fallacies of Distraction • False Dilemma: two choices are given when in fact there are three options • From Ignorance: because something is not known to be true, it is assumed to be false • Slippery Slope: a series of increasingly unacceptable consequences is drawn • Complex Question: two unrelated points are conjoined as a single proposition Each of these fallacies is characterized by the illegitimate use of a logical operator in order to distract the reader from the apparent falsity of a certain proposition. False Dilemma Definition: A limited number of options (usually two) is given, while in reality there are more options. A false dilemma is an illegitimate use of the "or" operator. Examples: (i) Either you're for me or against me. (ii) America: love it or leave it. (iii) Either support Meech Lake or Quebec will separate. (iv) Every person is either wholly good or wholly evil. Identifying Proof: Identify the options given and show (with an example) that there is an additional option. -

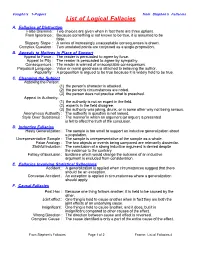

List of Logical Fallacies A

Vaughn's 1-Pagers from Stephen's Fallacies List of Logical Fallacies A. Fallacies of Distraction False Dilemma : Two choices are given when in fact there are three options. From Ignorance : Because something is not known to be true, it is assumed to be false. Slippery Slope : A series of increasingly unacceptable consequences is drawn. Complex Question : Two unrelated points are conjoined as a single proposition. B. Appeals to Motives in Place of Support Appeal to Force : The reader is persuaded to agree by force. Appeal to Pity : The reader is persuaded to agree by sympathy. Consequences : The reader is warned of unacceptable consequences. Prejudicial Language : Value or moral goodness is attached to believing the author. Popularity : A proposition is argued to be true because it is widely held to be true. C. Changing the Subject Attacking the Person: (1) the person's character is attacked. (2) the person's circumstances are noted. (3) the person does not practice what is preached. Appeal to Authority: (1) the authority is not an expert in the field. (2) experts in the field disagree. (3) the authority was joking, drunk, or in some other way not being serious. Anonymous Authority : The authority in question is not named. Style Over Substance : The manner in which an argument (or arguer) is presented is felt to affect the truth of the conclusion. D. Inductive Fallacies Hasty Generalization : The sample is too small to support an inductive generalization about a population. Unrepresentative Sample : The sample is unrepresentative of the sample as a whole. False Analogy : The two objects or events being compared are relevantly dissimilar.