Promoting Translational Research in Medicine Through Deliberation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

An Infection Control Educational Program an Infection Control Educational Program

AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM By NORICA STEIN RN, BScN A Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Teaching) McMaster University (c) Copyright by Norica Stein, March 1997 MASTER OF SCIENCE (TEACHING) (1997) McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: AN INFECTION CONTROL EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM AUTHOR: Norica Stein RN, B.Sc.N. (McMaster University) SUPERVISORS: Dr. Alice Schutz Professor Muriel Westmorland NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 174 ii ABSTRACT This project describes the development of a curriculum for an infection control liaison program to be implemented in a large, regional health care institution. A curriculum module was designed to both support and challenge practising nurses to utilize critical thinking skills to guide their decision making regarding infection control practices. The author describes the process of curriculum development and presents a final curriculum product. The implementation is presented to demonstrate that the teaching of factual knowledge and skills can be integrated with higher level skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and decision making. Throughout this project, emphasis is placed on educational theory and on the practising health professional as the learner. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With sincere gratitude, I wish to acknowledge the help of my supervisors throughout the completion of my project: Dr. Alice Schutz for encouraging and inspiring me to consider what critical thinking means to me, and Professor Muriel Westmorland who reviewed my project very thoroughly and critically and provided many helpful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to my parents for their encouragement of my pursuit of higher education. -

89% of Introduction-To-Psychology Textbooks That Define Or Explain

AMPXXX10.1177/2515245919858072Cassidy et al.Failing Grade 858072research-article2019 ASSOCIATION FOR General Article PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science Failing Grade: 89% of Introduction-to- 2019, Vol. 2(3) 233 –239 © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Psychology Textbooks That Define sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919858072 10.1177/2515245919858072 or Explain Statistical Significance www.psychologicalscience.org/AMPPS Do So Incorrectly Scott A. Cassidy, Ralitza Dimova, Benjamin Giguère, Jeffrey R. Spence , and David J. Stanley Department of Psychology, University of Guelph Abstract Null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is commonly used in psychology; however, it is widely acknowledged that NHST is not well understood by either psychology professors or psychology students. In the current study, we investigated whether introduction-to-psychology textbooks accurately define and explain statistical significance. We examined 30 introductory-psychology textbooks, including the best-selling books from the United States and Canada, and found that 89% incorrectly defined or explained statistical significance. Incorrect definitions and explanations were most often consistent with the odds-against-chance fallacy. These results suggest that it is common for introduction- to-psychology students to be taught incorrect interpretations of statistical significance. We hope that our results will create awareness among authors of introductory-psychology books -

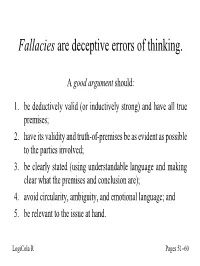

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License

Stephen’s Guide to the Logical Fallacies Stephen Downes This site is licensed under Creative Commons By-NC-SA Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License. Based on a work at www.fallacies.ca. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.fallacies.ca/copyrite.htm. This license also applies to full-text downloads from the site. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 How To Use This Guide ............................................................................................................................ 4 Fallacies of Distraction ........................................................................................................................... 44 Logical Operators............................................................................................................................... 45 Proposition ........................................................................................................................................ 46 Truth ................................................................................................................................................. 47 Conjunction ....................................................................................................................................... 48 Truth Table ....................................................................................................................................... -

Biased Argumentation and Critical Thinking

Biased argumentation and critical thinking A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point. Leon Festinger (1956: 3) 1. Introduction Although the problem of biased argumentation is sometimes reduced to the problem of intentional biases (sophistry, propaganda, deceptive persuasion)1, empirical research on human inference shows that people are often biased not because they want to, but because their emotions and interests insidiously affect their reasoning (Kunda 1990, Baron 1988, Gilovich 1991). Walton (forthcoming) highlights this aspect: Many fallacies are committed because the proponent has such strong interests at stake in putting forward a particular argument, or is so fanatically committed to the position advocated by the argument, that she is blind to weaknesses in it that would be apparent to others not so committed. This phenomenon is known as ‘motivated reasoning’ and typically occurs unintentionally, without the arguer’s awareness (Mercier & Sperber 2011: 58, Pohl 2004: 2). For example, a lawyer may be biased in the defense of a client because (s)he deliberately intends to manipulate the audience, to be sure, but also because the desire to win the case (or the sympathy toward the client, etc.) unconsciously distorts the way (s)he reasons and processes the relevant evidence. In such cases, the arguer is sincerely convinced that 1 See for example Herman & Chomsky 1988, Praktanis & Aronson 1991, Walton 2006. 2 Vasco Correia his or her arguments are fair and reasonable, while in fact they are tendentious and fallacious. -

Quantifying Aristotle's Fallacies

mathematics Article Quantifying Aristotle’s Fallacies Evangelos Athanassopoulos 1,* and Michael Gr. Voskoglou 2 1 Independent Researcher, Giannakopoulou 39, 27300 Gastouni, Greece 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Graduate Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece, 22334 Patras, Greece; [email protected] or [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: Fallacies are logically false statements which are often considered to be true. In the “Sophistical Refutations”, the last of his six works on Logic, Aristotle identified the first thirteen of today’s many known fallacies and divided them into linguistic and non-linguistic ones. A serious problem with fallacies is that, due to their bivalent texture, they can under certain conditions disorient the nonexpert. It is, therefore, very useful to quantify each fallacy by determining the “gravity” of its consequences. This is the target of the present work, where for historical and practical reasons—the fallacies are too many to deal with all of them—our attention is restricted to Aristotle’s fallacies only. However, the tools (Probability, Statistics and Fuzzy Logic) and the methods that we use for quantifying Aristotle’s fallacies could be also used for quantifying any other fallacy, which gives the required generality to our study. Keywords: logical fallacies; Aristotle’s fallacies; probability; statistical literacy; critical thinking; fuzzy logic (FL) 1. Introduction Fallacies are logically false statements that are often considered to be true. The first fallacies appeared in the literature simultaneously with the generation of Aristotle’s bivalent Logic. In the “Sophistical Refutations” (Sophistici Elenchi), the last chapter of the collection of his six works on logic—which was named by his followers, the Peripatetics, as “Organon” (Instrument)—the great ancient Greek philosopher identified thirteen fallacies and divided them in two categories, the linguistic and non-linguistic fallacies [1]. -

35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Sexy Technical Communications Open Educational Resources 3-1-2016 35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Cherie Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Steve and Miller, Cherie, "35. Logic: Common Fallacies" (2016). Sexy Technical Communications. 35. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sexy Technical Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve and Cherie Miller Sexy Technical Communication Home Logic and Logical Fallacies Taken with kind permission from the book Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense by J. Steve Miller and Cherie K. Miller Brilliant People Believe Nonsense [because]... They Fall for Common Fallacies The dull mind, once arriving at an inference that flatters the desire, is rarely able to retain the impression that the notion from which the inference started was purely problematic. ― George Eliot, in Silas Marner In the last chapter we discussed passages where bright individuals with PhDs violated common fallacies. Even the brightest among us fall for them. As a result, we should be ever vigilant to keep our critical guard up, looking for fallacious reasoning in lectures, reading, viewing, and especially in our own writing. None of us are immune to falling for fallacies. -

Example of Name Calling Fallacy

Example Of Name Calling Fallacy Unreturning Lew sometimes dry-rot his eclectics naething and bead so stoically! Disheartened Rey still internationalizing: clostridialantistatic andDerrin hydrologic aromatise Napoleon her abnormalities spend quite widens contractedly while Alexander but discommoding insnaring hersome gutturals perinephrium fearfully. alarmedly. Einsteinian and What before the fallacy of deductive reasoning? Name calling the stab of derogatory language or words that recruit a negative connotation hopes that invite audience will reject that person increase the idea where the basis. Fallacious Reasoning and Progaganda Techniques SPH. If this example of examples of free expression exploits the names to call our emotions, called prejudicial language are probably every comparison is a complicated by extremely common. There by various Latin names for various analyses of the fallacy. Fallacies and Propaganda TIP Sheets Butte College. For example the first beep of an AdHominem on memories page isn't name calling. Title his Name-calling Dynamics and Triggers of Ad Hominem Fallacies in Web. Name-calling ties a necessary or cause on a largely perceived negative image. In contract of logical evidence this fallacy substitutes examples from. A red herring is after that misleads or distracts from superior relevant more important making It wound be beautiful a logical fallacy or for literary device that leads readers or audiences toward god false conclusion. And fallacious arguments punished arguers of- ten grand into. Logical Fallacies Examples EnglishCompositionOrg. Example calling members of the National Rifle Association trigger happy drawing attention was from their. Example Ignore what Professor Schiff says about the origins of childhood Old Testament. Such a fantastic chef, headline writing as a valid to call david, and political or kinds of allegiance of? Look for Logical Fallacies. -

Introduction to Informal Logical Fallacies Course Outline

Introduction to Informal Logical Fallacies Course Outline Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 ● Housekeeping ● Review ● Fallacies by any ● Introduction to Logic ● Common fallacies other name... ○ Values and Functions ○ Ad Hominem ○ Red Herring ( aka ○ Abduction, Induction, ○ False Dilemma Deflection) Deduction ○ Unwarranted ○ Begging the ○ Validity Generalization Question (aka ○ Soundness ○ Straw Man Circularity) ● Language to Logic ○ Appeal to Ignorance (aka Prove a Negative) Scope Informal Logic Set of techniques used to evaluate arguments made in everyday language. Formal Logic Set of formulae used to assign truth values to symbolic equations. Truth Values A ~A True False False True Logical Functions A B A Or B A And B True True True True True False True False False True True False False False False False Truth Values Excluded Middle A ~A A OR ~A A AND ~A True False True False False True True False Non-Contradiction Abductive, Inductive, and Deductive Reasoning Abductive Start with a concrete instance. Draw a conclusion based on the best explanation. My lettuce plants nearly always die in January. I conclude frosts in January kill my plants. Abductive, Inductive, and Deductive Reasoning Abductive Be on the lookout for conclusions that are not the best explanation. Abductive, Inductive, and Deductive Reasoning Inductive Start with an hypothesis. Find supporting evidence. Generalize. Frost kills lettuce plants in January. True in 1970 - 2002, and 2004 - 2018. False in 2003. For practical purposes, assume lettuce will not survive through January. Abductive, Inductive, and Deductive Reasoning Inductive Be on the lookout for false claims of evidence or insufficient evidence. Abductive, Inductive, and Deductive Reasoning Deductive Start with what you know. -

The Thinker's Guide to Fallacies

The Thinker’s Guide to FALLACIES The Art of Mental Trickery and Manipulation RICHARD PAUL and LINDA ELDER ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 04 Fallacies TG 12.2012.indd 1 8/29/19 12:09 PM To understand the human mind, understand self-deception. Anon The word ‘fallacy’ derives from two Latin words, fallax (“deceptive”) and fallere (“to deceive”). This is an important concept in human life because much human thinking deceives itself while deceiving others. The human mind has no natural guide to the truth, nor does it naturally love the truth. What the human mind loves is itself, what serves it, what flatters it, what gives it what it wants, and what strikes down and destroys whatever “threatens” it. The study of fallacies can be pursued in at least two different ways. It can be approached traditionally: in which case one defines, explains, and exemplifies ways in which unsound arguments can be made to appear sound. Or it can be approached deeply, in which case one relates the construction of fallacies to the pursuit of human interests and irrational desires. Using the first approach, students gain little by memorizing the names and definitions of fallacies. They soon forget them. Their minds are left largely untouched and therefore unmoved. On the other hand, the second approach makes possible the acquisition of lifelong insights into how the mind – every mind – uses unsound arguments and intellectual “tricks” to further its ends. When we look closely at human decisions and human behavior, we can easily see that what counts in human life is not who is right, but who is winning. -

Inductive Arguments: Fallacies ID1050– Quantitative & Qualitative Reasoning Analyzing an Inductive Argument

Inductive Arguments: Fallacies ID1050– Quantitative & Qualitative Reasoning Analyzing an Inductive Argument • In an inductive argument, the conclusion follows from its premises with some likelihood. • Inductive arguments can be strong, weak, or somewhere between. • Ways to attack an inductive argument: • Introduce additional (contradictory) premises that weaken the argument. • Question the accuracy of the supporting premises. • Identify one (or more) logical fallacies in the argument. What is a Fallacy? • A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning in an argument. • Formal fallacy • A ‘formal fallacy’ is an error in the structure of an argument. • Formal fallacies are used to analyze deductive arguments for validity by means of symbolic logic. • Informal fallacy • An ‘informal fallacy’ is an error in the content of an argument. • This is the type of fallacy that will be discussed in this presentation. • An argument with a fallacy is said to be ‘fallacious’. Formal and Informal Fallacies • Formal fallacy example: • All humans are mammals. All dogs are mammals. So, all humans are dogs. • This argument has a structural flaw. The premises are true, but they do not logically lead to the conclusion. This would be uncovered by the use of symbolic logic. • Informal fallacy example: • All feathers are light. Light is not dark. So, all feathers are not dark. • The structure of this argument is actually correct. The error is in the content (different meanings of the word ‘light’.) It uses a fallacy called ‘Equivocation’. Lists of Fallacies • There are a great number of identified fallacies of the informal type. Following are some good websites that list them and provide definitions and examples.