Problems in Argument Analysis and Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sentimentalism and Moral Dilemmas

Sentimentalism and Moral Dilemmas András Szigeti Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: András Szigeti, Sentimentalism and Moral Dilemmas, 2015, Dialectica, (69), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1746-8361.12087 Copyright: Wiley: 12 months http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-118875 Sentimentalism and Moral Dilemmas András SZIGETI UiT The Arctic University of Norway/Linköping University Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: It is sometimes said that certain hard moral choices constitute tragic moral dilemmas in which no available course of action is justifiable, and so the agent is blameworthy whatever she chooses. This paper criticizes a certain approach to the debate about moral dilemmas and considers the metaethical implications of the criticisms. The approach in question has been taken by many advocates as well as opponents of moral dilemmas who believe that analyzing the emotional response of the agent is the key to the debate about moral dilemmas. The metaethical position this approach is most naturally associated with is sentimentalism. Sentimentalists claim that evaluation, and in particular moral evaluation, crucially depends on human sentiment. This paper is not concerned with the question whether moral dilemmas exist, but rather with emotion-based arguments used on both sides of the debate. The first aim of the paper is to show that emotion-based arguments by friends or foes of moral dilemmas cannot garner support from sentimentalism. The second aim is to show that this constitutes a serious problem for sentimentalism. -

Argumentation Theory and Practical Discourse

Ulrich's Bimonthly 1 Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly Formerly "Picture of the Month" November-December 2009 Reflections on Reflective Practice (6b/7) HOME Part 6b: Argumentation theory and practical discourse – Habermas 2 Previous | Next WER NER ULRICH'S BIO We are still engaged in an effort to review the practical philosophies of For a hyperlinked overview of all issues of "Ulrich's PUBLICATIONS Aristotle, Kant, and Habermas, to see what we can learn from them for the Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the Month" series, READINGS ON CSH purpose of grounding reflective practice philosophically. The discussions of see the site map DOWNLOADS Aristotle and Kant were detailed but still found place within a single essay PDF file HARD COPIES each. The current discussion of Habermas, however, takes more space and I CRITICAL SYSTEMS have therefore decided to split it into three parts (see the right-hand note). HEURISTICS (CSH) Note: This is the second of three parts reviewing the Before we continue with the second part, it may help returning readers if I CST FOR PROFESSIONALS implications of the work of & CITIZENS briefly sum up where we stand; should you be new to the Bimonthly, I Habermas for reflective professional practice. The first A TRIBUTE TO C.W. CHURCHMAN recommend you read the previous Part 6a/7 to facilitate your reading of the part appeared in the Bimonthly of September-October 2009; LUG ANO SUMMER SCHOOL present Part 6b/7 (click on the "Previous" button at the top right of this page). the third and concluding part is planned for a later ULRICH'S BIMONTHLY Bimonthly. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

89% of Introduction-To-Psychology Textbooks That Define Or Explain

AMPXXX10.1177/2515245919858072Cassidy et al.Failing Grade 858072research-article2019 ASSOCIATION FOR General Article PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science Failing Grade: 89% of Introduction-to- 2019, Vol. 2(3) 233 –239 © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Psychology Textbooks That Define sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919858072 10.1177/2515245919858072 or Explain Statistical Significance www.psychologicalscience.org/AMPPS Do So Incorrectly Scott A. Cassidy, Ralitza Dimova, Benjamin Giguère, Jeffrey R. Spence , and David J. Stanley Department of Psychology, University of Guelph Abstract Null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is commonly used in psychology; however, it is widely acknowledged that NHST is not well understood by either psychology professors or psychology students. In the current study, we investigated whether introduction-to-psychology textbooks accurately define and explain statistical significance. We examined 30 introductory-psychology textbooks, including the best-selling books from the United States and Canada, and found that 89% incorrectly defined or explained statistical significance. Incorrect definitions and explanations were most often consistent with the odds-against-chance fallacy. These results suggest that it is common for introduction- to-psychology students to be taught incorrect interpretations of statistical significance. We hope that our results will create awareness among authors of introductory-psychology books -

Mathematics and Computation

Mathematics and Computation Mathematics and Computation Ideas Revolutionizing Technology and Science Avi Wigderson Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright c 2019 by Avi Wigderson Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to [email protected] Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Control Number: 2018965993 ISBN: 978-0-691-18913-0 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Editorial: Vickie Kearn, Lauren Bucca, and Susannah Shoemaker Production Editorial: Nathan Carr Jacket/Cover Credit: THIS INFORMATION NEEDS TO BE ADDED WHEN IT IS AVAILABLE. WE DO NOT HAVE THIS INFORMATION NOW. Production: Jacquie Poirier Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Kathryn Stevens Copyeditor: Cyd Westmoreland This book has been composed in LATEX The publisher would like to acknowledge the author of this volume for providing the camera-ready copy from which this book was printed. Printed on acid-free paper 1 Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Dedicated to the memory of my father, Pinchas Wigderson (1921{1988), who loved people, loved puzzles, and inspired me. Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, 1943 Contents Acknowledgments 1 1 Introduction 3 1.1 On the interactions of math and computation..........................3 1.2 Computational complexity theory.................................6 1.3 The nature, purpose, and style of this book............................7 1.4 Who is this book for?........................................7 1.5 Organization of the book......................................8 1.6 Notation and conventions..................................... -

Beardsley's Theory of Analogy

INFORMAL LOGIC XI.3, Fall 1989 Beardsley's Theory of Analogy EVELYN M. BARKER The University of Maryland 1. Is the Argument from Analogy a consequences of an "abdication of Fallacy? statesmanship."2 Kissinger cites historical analogy as the only basis for sound judg In the various editions of Practical Logic ment in international diplomacy: and Thinking Straight Monroe Beardsley History is the only experience on which pioneered informal logic, the assessment of statesmen can draw. But it does not teach reasoning techniques employed in actual its lessons automatically. It demonstrates the human situations. 1 Although acknowledg consequences of comparable situations, but ing the prominence of analogies in reason each generation has to determine what situa ing, he contended that analogy has some tions are in fact comparable. heuristic uses, but an argument based on one Such analogical arguments, as Kissinger is inherently fallacious: points out, are directed to finding suitable Analogies illustrate, and they lead to premises for wise and prudent action. hypotheses, but thinking in terms of analogy Beardsley's intellectualist approach limits becomes fallacious when the analogy is us rational argumentation to asserting premises ed as a reason for a principle. This fallacy as evidence for the truth of a conclusion. is called the "argument from analogy." Consequently he overlooks or misconceives (PL 107) the character of some forms of analogical Beardsley's view implies that no serious argument prevalent in practical reasoning. reasoner will use analogies between things It is misleading to speak of "the argument in drawing conclusions, or be persuaded by from analogy," as Beardsley does, as if all another's introduction of them. -

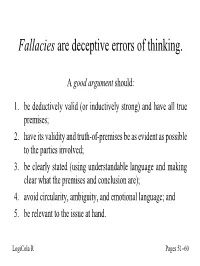

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Replies to Commentators on the Concept of Argument: Clarifying Themes, Answering Questions, Settling Objections Harald R

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:52 a.m. Informal Logic Replies to Commentators on The Concept of Argument: Clarifying Themes, Answering Questions, Settling Objections Harald R. Wohlrapp Volume 37, Number 4, 2017 Article abstract The paper provides a series of responses to the papers published in Vol. 37, No. URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042917ar 3, of this journal that explored the ideas in Harald Wohlrapp’s The Concept of DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v37i4.5004 Argument (2014), where arguing is understood as the theoretical or theory-forming activity that can be found in research of all kinds. Thus, the See table of contents approach taken focuses on the validity of theses. This approach is clarified further as the author considers points raised by his commentators and provides answers and, where necessary, corrections. Publisher(s) Informal Logic ISSN 0824-2577 (print) 2293-734X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Wohlrapp, H. (2017). Replies to Commentators on The Concept of Argument: Clarifying Themes, Answering Questions, Settling Objections. Informal Logic, 37(4), 247–321. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v37i4.5004 Copyright (c), 2017 Harald R. Wohlrapp This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. -

Developments in Argumentation Theory

Developments in Argumentation Theory Frans H van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst, University of Amsterdam Abstract In this paper, a survey is provided of the state of the art in argumentation theory. Some of the most significant approaches of the past two decades are discussed: Informal Logic, the formal theory of fallacies, formal dialectics, pragma-dialectics, Radical Argumentativism, and the modem revival of rhetoric. The survey is based not only on books, but also on papers published in professional joumals or included in conference proceedings. 1. Introduction Argumentation is a speech act complex aimed at resolving a difference of opinion. According to a prominent handbook definition, it is a verbal and social activity of reason carried out by a speaker or writer concerned with increasing (or decreasing) the acceptability of a controversial standpoint for a listener or reader; the con stellation of propositions brought to bear in this endeavour is intended to justify (or refute) the standpoint before a rational judge.\ Argumentation theory is the name given to the (systematic results of the) study of this discourse phenomenon. Argumentation theory studies the production, analysis and evaluation of argumen tation with a view of developing adequate criteria for determining the validity of the point of departure and presentational layout of argumentative discourse. The constellation of propositions advanced in argumentation is often referred to by the term argument, particularly by logicians and philosophers. This may lead to confusion because (in English) the word 'argument' has various meanings. Apart from (a) a reason and (b) a logical inference of a conclusion from one or more premisses, 'argument' can also denote (c) a discussion and (d) a quarrel. -

Teorie Vědy / Theory of Science / Xl / 2018 / 2 The

TEORIE VĚDY / THEORY OF SCIENCE / XL / 2018 / 2 ////// studie / article //////////////////////////////////////////// THE PARADOX OF Paradox moralistického omylu: MORALISTIC FALLACY: argument proti nebezpečné A CASE AGAINST THE znalosti DANGEROUS KNOWLEDGE Abstrakt: V článku je rozveden Abstract: In this article, the concept koncept moralistického omylu, of moralistic fallacy introduced by který předložil B. D. Davis. Jsou B. D. Davis is elaborated on in more diskutovány základní charakteris- detail. Th e main features of this fal- tiky tohoto omylu s cílem představit lacy are discussed, and its general jeho obecnou formu. Moralistický form is presented. Th e moralistic omyl má přitom nechtěné následky, fallacy might have some undesirable z nichž některé dokonce mohou být outcomes. Some of them might even v přímém rozporu s původní morální be in direct confl ict to the original pozicí, která stojí v začátku tohoto moral position. If this occurs, it samotného omylu. Pokud takovýto is possible to characterize it as stav nastane, lze ukázat, že mora- a paradox of moralistic fallacy. Th e listický omyl způsobuje paradox. possibility of this paradox provides Možnost takovéhoto paradoxu pak a further reason not to prevent any poskytuje důvod k tomu, aby bylo scientifi c inquiries and not to depict odmítnuto omezování vědeckého any knowledge as dangerous. zkoumání a aby nebyla žádná zna- lost charakterizována jako nebez- Keywords: moralistic fallacy; pečná. reverse naturalistic fallacy; Bernard D. Davis; paradox of moralistic Klíčová slova: moralistický fallacy; dangerous knowledge omyl; reverzní naturalistický omyl; Bernard D. Davis; paradox moralistického omylu; nebezpečná znalost TOMÁŠ ONDRÁČEK Department of Corporate Economy, Masaryk University Lipová 41a, 602 00, Brno, Czech Republic email / [email protected] 191 Tomáš Ondráček Introduction Is there knowledge which should be considered as dangerous and unwanted? Knowledge which should be prevented from acquiring? Th ere have been many attempts to prohibit some knowledge in history. -

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: a Critical Appreciation of Doury's Account

The Argument Form “Appeal to Galileo”: A Critical Appreciation of Doury’s Account MAURICE A. FINOCCHIARO Department of Philosophy University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV 89154-5028 USA [email protected] Abstract: Following a linguistic- Résumé: En poursuivant une ap- descriptivist approach, Marianne proche linguistique-descriptiviste, Doury has studied debates about Marianne Doury a étudié les débats “parasciences” (e.g. astrology), dis- sur les «parasciences » (par exem- covering that “parascientists” fre- ple, l'astrologie), et a découvert que quently argue by “appeal to Galileo” les «parasavants» raisonnent souvent (i.e., defend their views by compar- en faisant un «appel à Galilée" (c.-à- ing themselves to Galileo and their d. ils défendent leurs points de vue opponents to the Inquisition); oppo- en se comparant à Galileo et en nents object by criticizing the analo- comparant leurs adversaires aux gy, charging fallacy, and appealing juges de l’Inquisition). Les adver- to counter-examples. I argue that saires des parasavant critiquent Galilean appeals are much more l'analogie en la qualifiant de soph- widely used, by creationists, global- isme, et en construisant des contre- warming skeptics, advocates of “set- exemples. Je soutiens que les appels tled science”, great scientists, and à Galilée sont beaucoup plus large- great philosophers. Moreover, sever- ment utilisés, par des créationnistes, al subtypes should be distinguished; des sceptiques du réchauffement critiques questioning the analogy are planétaire, des défenseurs de la «sci- proper; fallacy charges are problem- ence établie», des grands scien- atic; and appeals to counter- tifiques, et des grands philosophes. examples are really indirect critiques En outre, on doit distinguer plusieurs of the analogy. -

Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings

SUMMER 2014, VOL. 29, NO. 2 35 Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings School of Arts and Humanities Nottingham Trent University, UK Abstract 7KHVWXG\RIWKHIDOODFLHVKDVFKDQJHGDOPRVWEH\RQGUHFRJQLWLRQVLQFH&KDUOHV+DPEOLQFDOOHG IRUDUDGLFDOUHDSSUDLVDORIWKLVDUHDRIORJLFDOLQTXLU\LQKLVERRN)DOODFLHV7KH³ZLWOHVV H[DPSOHVRIKLVIRUEHDUV´WRZKLFK+DPEOLQUHIHUUHGKDYHODUJHO\EHHQUHSODFHGE\PRUH authentic cases of the fallacies in actual use. It is now not unusual for fallacy and argumentation theorists to draw on actual sources for examples of how the fallacies are used in our everyday UHDVRQLQJ+RZHYHUDQDVSHFWRIWKLVPRYHWRZDUGVJUHDWHUDXWKHQWLFLW\LQWKHVWXG\RIWKH fallacies, an aspect which has been almost universally neglected, is the attempt to subject the fallacies to empirical testing of the type which is more commonly associated with psychological experiments on reasoning. This paper addresses this omission in research on the fallacies by examining how subjects use two fallacies – circular argument and analogical argument – during a reasoning task in which subjects are required to consider a number of public health scenarios. Results are discussed in relation to a view of the fallacies as cognitive heuristics that facilitate reasoning in a context of uncertainty. Keywords: analogical argument, circular argument, heuristic, informal fallacy, public health, reasoning, uncertainty I. Introduction puns, anecdotes, and witless examples of his forbears. The study of the fallacies has changed :KHUHSKLORVRSKLFDOUHÀHFWLRQRQWKH considerably in