* Magnetic Scalar Potential * Magnetic Vector Potential Magnetic Potentials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electrostatics Vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics

Electrostatics vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics Stationary charges ⇒ Constant Electric Field Steady currents ⇒ Constant Magnetic Field Coulomb’s Law Biot-Savart’s Law 1 ̂ ̂ 4 4 (Inverse Square Law) (Inverse Square Law) Electric field is the negative gradient of the Magnetic field is the curl of magnetic vector electric scalar potential. potential. 1 ′ ′ ′ ′ 4 |′| 4 |′| Electric Scalar Potential Magnetic Vector Potential Three Poisson’s equations for solving Poisson’s equation for solving electric scalar magnetic vector potential potential. Discrete 2 Physical Dipole ′′′ Continuous Magnetic Dipole Moment Electric Dipole Moment 1 1 1 3 ∙̂̂ 3 ∙̂̂ 4 4 Electric field cause by an electric dipole Magnetic field cause by a magnetic dipole Torque on an electric dipole Torque on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric force on an electric dipole Magnetic force on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric Potential Energy Magnetic Potential Energy of an electric dipole of a magnetic dipole Electric Dipole Moment per unit volume Magnetic Dipole Moment per unit volume (Polarisation) (Magnetisation) ∙ Volume Bound Charge Density Volume Bound Current Density ∙ Surface Bound Charge Density Surface Bound Current Density Volume Charge Density Volume Current Density Net , Free , Bound Net , Free , Bound Volume Charge Volume Current Net , Free , Bound Net ,Free , Bound 1 = Electric field = Magnetic field = Electric Displacement = Auxiliary -

Chapter 2 Introduction to Electrostatics

Chapter 2 Introduction to electrostatics 2.1 Coulomb and Gauss’ Laws We will restrict our discussion to the case of static electric and magnetic fields in a homogeneous, isotropic medium. In this case the electric field satisfies the two equations, Eq. 1.59a with a time independent charge density and Eq. 1.77 with a time independent magnetic flux density, D (r)= ρ (r) , (1.59a) ∇ · 0 E (r)=0. (1.77) ∇ × Because we are working with static fields in a homogeneous, isotropic medium the constituent equation is D (r)=εE (r) . (1.78) Note : D is sometimes written : (1.78b) D = ²oE + P .... SI units D = E +4πP in Gaussian units in these cases ε = [1+4πP/E] Gaussian The solution of Eq. 1.59 is 1 ρ0 (r0)(r r0) 3 D (r)= − d r0 + D0 (r) , SI units (1.79) 4π r r 3 ZZZ | − 0| with D0 (r)=0 ∇ · If we are seeking the contribution of the charge density, ρ0 (r) , to the electric displacement vector then D0 (r)=0. The given charge density generates the electric field 1 ρ0 (r0)(r r0) 3 E (r)= − d r0 SI units (1.80) 4πε r r 3 ZZZ | − 0| 18 Section 2.2 The electric or scalar potential 2.2 TheelectricorscalarpotentialFaraday’s law with static fields, Eq. 1.77, is automatically satisfied by any electric field E(r) which is given by E (r)= φ (r) (1.81) −∇ The function φ (r) is the scalar potential for the electric field. It is also possible to obtain the difference in the values of the scalar potential at two points by integrating the tangent component of the electric field along any path connecting the two points E (r) d` = φ (r) d` (1.82) − path · path ∇ · ra rb ra rb Z → Z → ∂φ(r) ∂φ(r) ∂φ(r) = dx + dy + dz path ∂x ∂y ∂z ra rb Z → · ¸ = dφ (r)=φ (rb) φ (ra) path − ra rb Z → The result obtained in Eq. -

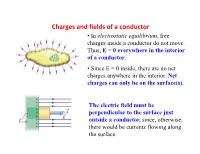

Charges and Fields of a Conductor • in Electrostatic Equilibrium, Free Charges Inside a Conductor Do Not Move

Charges and fields of a conductor • In electrostatic equilibrium, free charges inside a conductor do not move. Thus, E = 0 everywhere in the interior of a conductor. • Since E = 0 inside, there are no net charges anywhere in the interior. Net charges can only be on the surface(s). The electric field must be perpendicular to the surface just outside a conductor, since, otherwise, there would be currents flowing along the surface. Gauss’s Law: Qualitative Statement . Form any closed surface around charges . Count the number of electric field lines coming through the surface, those outward as positive and inward as negative. Then the net number of lines is proportional to the net charges enclosed in the surface. Uniformly charged conductor shell: Inside E = 0 inside • By symmetry, the electric field must only depend on r and is along a radial line everywhere. • Apply Gauss’s law to the blue surface , we get E = 0. •The charge on the inner surface of the conductor must also be zero since E = 0 inside a conductor. Discontinuity in E 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential • The electrostatic force is a conservative force, which means we can define an electrostatic potential energy. – We can therefore define electric potential or voltage. .Two parallel metal plates containing equal but opposite charges produce a uniform electric field between the plates. .This arrangement is an example of a capacitor, a device to store charge. • A positive test charge placed in the uniform electric field will experience an electrostatic force in the direction of the electric field. -

Review of Electrostatics and Magenetostatics

Review of electrostatics and magenetostatics January 12, 2016 1 Electrostatics 1.1 Coulomb’s law and the electric field Starting from Coulomb’s law for the force produced by a charge Q at the origin on a charge q at x, qQ F (x) = 2 x^ 4π0 jxj where x^ is a unit vector pointing from Q toward q. We may generalize this to let the source charge Q be at an arbitrary postion x0 by writing the distance between the charges as jx − x0j and the unit vector from Qto q as x − x0 jx − x0j Then Coulomb’s law becomes qQ x − x0 x − x0 F (x) = 2 0 4π0 jx − xij jx − x j Define the electric field as the force per unit charge at any given position, F (x) E (x) ≡ q Q x − x0 = 3 4π0 jx − x0j We think of the electric field as existing at each point in space, so that any charge q placed at x experiences a force qE (x). Since Coulomb’s law is linear in the charges, the electric field for multiple charges is just the sum of the fields from each, n X qi x − xi E (x) = 4π 3 i=1 0 jx − xij Knowing the electric field is equivalent to knowing Coulomb’s law. To formulate the equivalent of Coulomb’s law for a continuous distribution of charge, we introduce the charge density, ρ (x). We can define this as the total charge per unit volume for a volume centered at the position x, in the limit as the volume becomes “small”. -

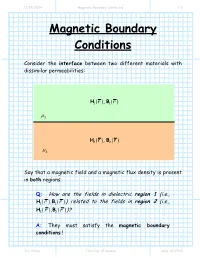

Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6

11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 1/6 Magnetic Boundary Conditions Consider the interface between two different materials with dissimilar permeabilities: HB11(r,) (r) µ1 HB22(r,) (r) µ2 Say that a magnetic field and a magnetic flux density is present in both regions. Q: How are the fields in dielectric region 1 (i.e., HB11()rr, ()) related to the fields in region 2 (i.e., HB22()rr, ())? A: They must satisfy the magnetic boundary conditions ! Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 2/6 First, let’s write the fields at the interface in terms of their normal (e.g.,Hn ()r ) and tangential (e.g.,Ht (r ) ) vector components: H r = H r + H r H1n ()r 1 ( ) 1t ( ) 1n () ˆan µ 1 H1t (r ) H2t (r ) H2n ()r H2 (r ) = H2t (r ) + H2n ()r µ 2 Our first boundary condition states that the tangential component of the magnetic field is continuous across a boundary. In other words: HH12tb(rr) = tb( ) where rb denotes to any point along the interface (e.g., material boundary). Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 11/28/2004 Magnetic Boundary Conditions 3/6 The tangential component of the magnetic field on one side of the material boundary is equal to the tangential component on the other side ! We can likewise consider the magnetic flux densities on the material interface in terms of their normal and tangential components: BHrr= µ B1n ()r 111( ) ( ) ˆan µ 1 B1t (r ) B2t (r ) B2n ()r BH222(rr) = µ ( ) µ2 The second magnetic boundary condition states that the normal vector component of the magnetic flux density is continuous across the material boundary. -

Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell’s Equations Matt Hansen May 20, 2004 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The basics 3 2.1 Static charges . 3 2.2 Moving charges . 4 2.3 Magnetism . 4 2.4 Vector operations . 5 2.5 Calculus . 6 2.6 Flux . 6 3 History 7 4 Maxwell’s Equations 8 4.1 Maxwell’s Equations . 8 4.2 Gauss’ law for electricity . 8 4.3 Gauss’ law for magnetism . 10 4.4 Faraday’s law . 11 4.5 Ampere-Maxwell law . 13 5 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction If asked, most people outside a physics department would not be able to identify Maxwell’s equations, nor would they be able to state that they dealt with electricity and magnetism. However, Maxwell’s equations have many very important implications in the life of a modern person, so much so that people use devices that function off the principles in Maxwell’s equations every day without even knowing it. 2 The basics 2.1 Static charges In order to understand Maxwell’s equations, it is necessary to understand some basic things about electricity and magnetism first. Static electricity is easy to understand, in that it is just a charge which, as its name implies, does not move until it is given the chance to “escape” to the ground. Amounts of charge are measured in coulombs, abbreviated C. 1C is an extraordi- nary amount of charge, chosen rather arbitrarily to be the charge carried by 6.41418 · 1018 electrons. The symbol for charge in equations is q, sometimes with a subscript like q1 or qenc. -

Electro Magnetic Fields Lecture Notes B.Tech

ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (II YEAR – I SEM) (2019-20) Prepared by: M.KUMARA SWAMY., Asst.Prof Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS Objectives: • To introduce the concepts of electric field, magnetic field. • Applications of electric and magnetic fields in the development of the theory for power transmission lines and electrical machines. UNIT – I Electrostatics: Electrostatic Fields – Coulomb’s Law – Electric Field Intensity (EFI) – EFI due to a line and a surface charge – Work done in moving a point charge in an electrostatic field – Electric Potential – Properties of potential function – Potential gradient – Gauss’s law – Application of Gauss’s Law – Maxwell’s first law, div ( D )=ρv – Laplace’s and Poison’s equations . Electric dipole – Dipole moment – potential and EFI due to an electric dipole. UNIT – II Dielectrics & Capacitance: Behavior of conductors in an electric field – Conductors and Insulators – Electric field inside a dielectric material – polarization – Dielectric – Conductor and Dielectric – Dielectric boundary conditions – Capacitance – Capacitance of parallel plates – spherical co‐axial capacitors. Current density – conduction and Convection current densities – Ohm’s law in point form – Equation of continuity UNIT – III Magneto Statics: Static magnetic fields – Biot‐Savart’s law – Magnetic field intensity (MFI) – MFI due to a straight current carrying filament – MFI due to circular, square and solenoid current Carrying wire – Relation between magnetic flux and magnetic flux density – Maxwell’s second Equation, div(B)=0, Ampere’s Law & Applications: Ampere’s circuital law and its applications viz. -

2 Classical Field Theory

2 Classical Field Theory In what follows we will consider rather general field theories. The only guiding principles that we will use in constructing these theories are (a) symmetries and (b) a generalized Least Action Principle. 2.1 Relativistic Invariance Before we saw three examples of relativistic wave equations. They are Maxwell’s equations for classical electromagnetism, the Klein-Gordon and Dirac equations. Maxwell’s equations govern the dynamics of a vector field, the vector potentials Aµ(x) = (A0, A~), whereas the Klein-Gordon equation describes excitations of a scalar field φ(x) and the Dirac equation governs the behavior of the four- component spinor field ψα(x)(α =0, 1, 2, 3). Each one of these fields transforms in a very definite way under the group of Lorentz transformations, the Lorentz group. The Lorentz group is defined as a group of linear transformations Λ of Minkowski space-time onto itself Λ : such that M M→M ′µ µ ν x =Λν x (1) The space-time components of Λ are the Lorentz boosts which relate inertial reference frames moving at relative velocity ~v. Thus, Lorentz boosts along the x1-axis have the familiar form x0 + vx1/c x0′ = 1 v2/c2 − x1 + vx0/c x1′ = p 1 v2/c2 − 2′ 2 x = xp x3′ = x3 (2) where x0 = ct, x1 = x, x2 = y and x3 = z (note: these are components, not powers!). If we use the notation γ = (1 v2/c2)−1/2 cosh α, we can write the Lorentz boost as a matrix: − ≡ x0′ cosh α sinh α 0 0 x0 x1′ sinh α cosh α 0 0 x1 = (3) x2′ 0 0 10 x2 x3′ 0 0 01 x3 The space components of Λ are conventional three-dimensional rotations R. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 8 MAGNETOQUASISTATIC FIELDS: SUPERPOSITION INTEGRAL AND BOUNDARY VALUE POINTS OF VIEW 8.0 INTRODUCTION MQS Fields: Superposition Integral and Boundary Value Views We now follow the study of electroquasistatics with that of magnetoquasistat ics. In terms of the flow of ideas summarized in Fig. 1.0.1, we have completed the EQS column to the left. Starting from the top of the MQS column on the right, recall from Chap. 3 that the laws of primary interest are Amp`ere’s law (with the displacement current density neglected) and the magnetic flux continuity law (Table 3.6.1). � × H = J (1) � · µoH = 0 (2) These laws have associated with them continuity conditions at interfaces. If the in terface carries a surface current density K, then the continuity condition associated with (1) is (1.4.16) n × (Ha − Hb) = K (3) and the continuity condition associated with (2) is (1.7.6). a b n · (µoH − µoH ) = 0 (4) In the absence of magnetizable materials, these laws determine the magnetic field intensity H given its source, the current density J. -

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We Present Magnetostatics in Comparison with Electrostatics

Magnetostatics: Part 1 We present magnetostatics in comparison with electrostatics. Sources of the fields: Electric field E: Coulomb’s law Magnetic field B: Biot-Savart law Forces exerted by the fields: Electric: F = qE Mind the notations, both Magnetic: F = qvB printed and hand‐written Does the magnetic force do any work to the charge? F B, F v Positive charge moving at v B Negative charge moving at v B Steady state: E = vB By measuring the polarity of the induced voltage, we can determine the sign of the moving charge. If the moving charge carriers is in a perfect conductor, then we can have an electric field inside the perfect conductor. Does this contradict what we have learned in electrostatics? Notice that the direction of the magnetic force is the same for both positive and negative charge carriers. Magnetic force on a current carrying wire The magnetic force is in the same direction regardless of the charge carrier sign. If the charge carrier is negative Carrier density Charge of each carrier For a small piece of the wire dl scalar Notice that v // dl A current-carrying wire in an external magnetic field feels the force exerted by the field. If the wire is not fixed, it will be moved by the magnetic force. Some work must be done. Does this contradict what we just said? For a wire from point A to point B, For a wire loop, If B is a constant all along the loop, because Let’s look at a rectangular wire loop in a uniform magnetic field B. -

Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System

Excerpt from the Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference 2010 Boston Modeling of Ferrofluid Passive Cooling System Mengfei Yang*,1,2, Robert O’Handley2 and Zhao Fang2,3 1M.I.T., 2Ferro Solutions, Inc, 3Penn. State Univ. *500 Memorial Dr, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] Abstract: The simplicity of a ferrofluid-based was to develop a model that supports results passive cooling system makes it an appealing from experiments conducted on a cylindrical option for devices with limited space or other container of ferrofluid with a heat source and physical constraints. The cooling system sink [Figure 1]. consists of a permanent magnet and a ferrofluid. The experiments involved changing the Ferrofluids are composed of nanoscale volume of the ferrofluid and moving the magnet ferromagnetic particles with a temperature- to different positions outside the ferrofluid dependant magnetization suspended in a liquid container. These experiments tested 1) the effect solvent. The cool, magnetic ferrofluid near the of bringing the heat source and heat sink closer heat sink is attracted toward a magnet positioned together and using less ferrofluid, and 2) the near the heat source, thereby displacing the hot, optimal position for the permanent magnet paramagnetic ferrofluid near the heat source and between the heat source and sink. In the model, setting up convective cooling. This paper temperature-dependent magnetic properties were explores how COMSOL Multiphysics can be incorporated into the force component of the used to model a simple cylinder representation of momentum equation, which was coupled to the such a cooling system. Numerical results from heat transfer module. The model was compared the model displayed the same trends as empirical with experimental results for steady-state data from experiments conducted on the cylinder temperature trends and for appropriate velocity cooling system. -

Chapter 2. Electrostatics

Chapter 2. Electrostatics Introduction to Electrodynamics, 3rd or 4rd Edition, David J. Griffiths 2.3 Electric Potential 2.3.1 Introduction to Potential We're going to reduce a vector problem (finding E from E 0 ) down to a much simpler scalar problem. E 0 the line integral of E from point a to point b is the same for all paths (independent of path) Because the line integral of E is independent of path, we can define a function called the Electric Potential: : O is some standard reference point The potential difference between two points a and b is The fundamental theorem for gradients states that The electric field is the gradient of scalar potential 2.3.2 Comments on Potential (i) The name. “Potential" and “Potential Energy" are completely different terms and should, by all rights, have different names. There is a connection between "potential" and "potential energy“: Ex: (ii) Advantage of the potential formulation. “If you know V, you can easily get E” by just taking the gradient: This is quite extraordinary: One can get a vector quantity E (three components) from a scalar V (one component)! How can one function possibly contain all the information that three independent functions carry? The answer is that the three components of E are not really independent. E 0 Therefore, E is a very special kind of vector: whose curl is always zero Comments on Potential (iii) The reference point O. The choice of reference point 0 was arbitrary “ambiguity in definition” Changing reference points amounts to adding a constant K to the potential: Adding a constant to V will not affect the potential difference: since the added constants cancel out.