Northern Coast Range Adaptive Management Area Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting O&C Lands: Mount Hebo

A fact sheet from Sept 2013 Bob Van Dyk Bob Van Dyk Bob Van Dyk Protecting O&C Lands Mount Hebo Location: Northern Oregon Coast Range Rising 3,175 feet from its densely forested surroundings, Mount Hebo is one of the highest peaks 11,310 Acres: in the northern Oregon Coast Range. The prominent Ecological value: Historical significance, lookout is a popular day hike for those willing to breathtaking vistas, hemlock and Douglas fir climb far above the massive hemlock and Douglas fir forests, and abundant wildflowers forest to fully experience the breathtaking scope of the Northwest’s landscape. Along the path, a traveler Economic value: Hiking and biking will find an abundance of towering trees and rare wildflowers. North of the mountain’s summit lies the last remaining roadless area in northwest Oregon, What are the O&C lands? providing a unique wild land experience in this part In 1866, Congress established a land-grant program for the Oregon of the state. This area should be forever protected & California (O&C) Railroad Co. to spur the completion of the as wilderness. rail line between Portland and San Francisco that required the company to sell the deeded land to settlers. Forty years later, when Pioneers dubbed the peak “Heave Ho” because of the the company failed to meet the terms of the agreement fully, the way it seemed to erupt from the surrounding forest. federal government reclaimed more than 2 million acres of mostly Over the years, the name “Heave Ho” morphed into forested land. Today, those O&C lands remain undeveloped and “Hebo.” These explorers discovered what Native are administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. -

Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 Minute Quadrangles)

(a-0g) R ago (na. 96-53 14. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR , U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Alatzi2/6 (Of (c,c) - R qo rite 6/6-53y Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 minute Quadrangles) by Parke D. Snavely, Jr.', Alan Niem 2 , Florence L. Wong', Norman S. MacLeod 3, and Tracy K. Calhoun 4 with major contributions by Diane L. Minasian' and Wendy Niem2 Open File Report 96-0534 1996 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American stratigraphic code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1/ U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA 94025 2/ Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97403 3/ Consultant, Vancouver, WA 98664 4/ U.S. Forest Service, Corvallis, OR 97339 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 GEOLOGIC SKETCH 2 DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS SURFICIAL DEPOSITS 7 BEDROCK UNITS Sedimentary and Volcanic Rocks 8 Intrusive Rocks 14 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 15 REFERENCES CITED 15 MAP SHEETS Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwestern Oregon Coast Range, scale 1:24,000, 2 sheets. Geologic Map of the Cascade Head Area, Northwest Oregon Coast Range (Neskowin, Nestucca Bay, Hebo, and Dolph 7.5 minute Quadrangles) by Parke D. Snavely, Jr., Alan Niem, Florence L. Wong, Norman S. MacLeod, and Tracy K. Calhoun with major contributions by Diane L. Minasian and Wendy Niem INTRODUCTION The geology of the Cascade Head (W.W. -

Oregon Silverspot Recovery Plan

PART I INTRODUCTION Overview The Oregon silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene hippolyta) is a small, darkly marked coastal subspecies of the Zerene fritillary, a widespread butterfly species in montane western North America. The historical range of the subspecies extends from Westport, Grays Harbor County, Washington, south to Del Norte County, California. Within its range, the butterfly is known to have been extirpated from at least 11 colonies (2 in Washington, 8 in Oregon, and 1 in California). We, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, listed the Oregon silverspot butterfly was listed as a threatened species with critical habitat in 1980 (USDI 1980; 45 FR 44935). We completed a recovery plan for this species in 1982 (USDI 1982). The species recovery priority number is 3, indicating a high degree of threat and high recovery potential (USDI 1983; 48 FR 43098). At the time of listing, the only viable population known was at Rock Creek-Big Creek in Lane County, Oregon, and was managed by the U.S. Forest Service (Siuslaw National Forest). The Siuslaw National Forest developed an implementation plan (Clady and Parsons 1984) to guide management of the species at Rock Creek-Big Creek and Mount Hebo (Mt. Hebo) in Tillamook County, Oregon. Additional Oregon silverspot butterfly populations were discovered at Cascade Head, Bray Point, and Clatsop Plains in Oregon, on the Long Beach Peninsula in Washington, and in Del Norte County in California. The probability of survival of four populations has been increased by management efforts of the Siuslaw National Forest and The Nature Conservancy, however, some threats to the species remain at all of the sites. -

Appendix F.3 Scenic Features in Study Area

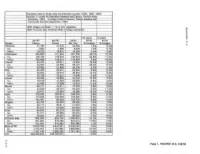

Population data for Study Area and individual counties (1980, 1990, 1993) Sources: 1) Center for Population Research and Census, Portland State University, 1994. 2) Oregon Census Abstract, Oregon Housing and Community Services Department, 1993. 1990: Oregon contained 1.1% of U.S. population 1990: 9-county area contained 36% of Oregon population ~ 'd (1) ::s 0...... (10 years) (3 years) >: Apr-80 Apr-90 Jul-93 80-90 90-93 t'%j County Census Census Est. Pop % Increase % Increase ...... Tillamook 21,164 21,670 22,900 1.9% 6.2% Inc. 7,892 7,969 8,505 1.0% 6.7% Uninc. 13,272 13,601 14,395 2.6% 6.8% Washington 245,860 311,654 351,000 26.7% 12.7% Inc. 105,162 162,544 180,344 64.6% 11.0% Uninc. 140,698 149,010 170,656 5.9% 14.5% Yamhill 55,332 65,551 70,900 18.5% 8.2% Inc. 34,840 43,965 48,161 26.2% 9.5% Uninc. 20,492 21,586 22,739 5.3% 5.3% Polk 45,203 49,541 53,600 9.6% 8.2% Inc. 30,054 34,310 36,554 14.2% 6.5% Uninc. 15,149 15,231 17,046 0.5% 11.9% lincoln 35,264 38,889 40,000 10.3% 2.9% Inc. 19,619 21,493 22,690 9.6% 5.6% Uninc. 15,645 17,396 17,310 11.2% -0.5% Benton 68,211 70,811 73,300 3.8% 3.5% Inc. 44,640 48,757 54,220 9.2% 11.2% Uninc. -

WOPR Salem District Resource Management Plan

Resource Management Plan 25 Salem District ROD and RMP 26 Resource Management Plan Resource Management Plan Planning Area The entire planning area analyzed in the Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Revision of the Resource Management Plans of the Western Oregon Bureau of Land Management (October 2008) includes all lands (private, local, state, and federal) in western Oregon. See Figure 1 (Entire planning area of the Western Oregon BLM resource management plan revisions). The Salem District Resource Management Plan and the coordinated resource management plans for the other districts affect BLM-administered lands in the BLM districts and counties of western Oregon that are listed in Table 1 (BLM districts and Oregon counties included in the planning area of the Western Oregon BLM resource management plan revisions). Table 1. BLM Districts And Oregon Counties Included In The Planning Area Of The Resource Management Plan Revisions BLM Districts Oregon Counties Coos Bay Benton Jackson Marion Eugene Clackamas Josephine Multnomah Lakeview (Klamath Falls Resource Area only) Clatsop Klamath Polk Medford Columbia Lane Tillamook Roseburg Coos Lincoln Washington Salem Curry Linn Yamhill Douglas Figure 1. Entire Planning Area Of The Western Oregon BLM Resource Management Plan Revisions 27 Salem District ROD and RMP The six coordinated resource management plans provide requirements for management of approximately 2,557,800 acres of federal land within the planning area. These BLM-administered lands are widely scattered and represent only about 11% of the planning area. Of the approximately 2,557,800 acres administered by the BLM, approximately 2,151,200 acres are managed primarily under the O&C Act and are commonly referred to as the O&C lands. -

Early Oligocene Intrusions in the Central Coast Range of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jeremiah Oxford for the degree of Master of Science in Geology presented on October 13, 2006. Title: Early Oligocene Intrusions in the Central Coast Range of Oregon: Petrography, Geochemistry, Geochronology, and Implications for the Tertiary Magmatic Evolution of the Cascadia Forearc Abstract approved: Adam Kent The Early Oligocene Oregon Coast Range Intrusions (OCRI) consist of gabbroic rocks and lesser alkalic intrusive bodies that were emplaced in marine sedimentary units and volcanic sequences within a Tertiary Cascadia forearc basin. The alkalic intrusions include nepheline syenite, camptonite, and alkaline basalt. The gabbros occur as dikes and differentiated sills. Presently, erosional remnants of the intrusions underlie much of the high topography along the axis of the central Oregon Coast Range. The intrusive suite is most likely associated with Tertiary oblique rifting of the North America continental margin. Dextral shear and extension along the continental margin may have been a consequence of northeast-directed oblique Farallon plate convergence. However, while both the gabbroic and alkaline OCRI appear to be related to tectonic extension, major and trace element geochemistry reveal separate parental magma sources between the two suites. The OCRI are part of a long-lived (42-30 Ma) magmatic forearc province that includes the Yachats Basalt and Cascade Head Basalt. The timing of Cascadia forearc magmatism correlates with a significant decrease in convergence rates between the Farallon and North American plates from 42 to 28 Ma. The OCRI are also contemporaneous with magmatism that occurred over a broad area of the Pacific Northwest (e.g. Western Cascades, John Day Formation). -

Map Extent 13 17 16 Grandrond E Tribal Eland S 8 9 10 11 Eola Village

D R L D A N O Travel Management D C 2 29 28 27 30 29 1 6 M Braun 28 1 31 32 33 31 32 6 5 4 3 34 35 36 31 32 33 33 33 34 35 Long Mountain Area 2 36 Tater Hill 12 1 SADDLE MTN MANAGEMENT 31 32 ClatsopCounty 36 SADDLE MTN 34 35 36 31 32 33 D 35 ColumCounty bia 34 7 11 6 11 6 5 4 4 N T. 12 R 3 2 5 4 Wildlife Management 7 8 1 TillamookCounty UNIT MANAGEMENT 6 5 4 3 2 1 3 2 1 6 5 4 K 3 2 12 1 6 5 Wash ing tonCounty R Sunset Highway Forest Wayside 4 3 2 1 6 5 9 10 4 3 18 O 10 Unit UNIT 10 7 11 7 8 8 17 15 14 F 11 12 9 18 God's Valley Salmonberry 7 8 9 12 17 10 Hoffman Hill H 13 16 14 13 11 12 Coyote Corner 7 8 26 Sunset Camp Neahkahnie 15 9 ¤£ 7 8 PrivateCooperators 19 T FOSS RD 10 11 12 9 10 11 12 7 !!!!!!!!! Mountain R 8 9 10 17 16 20 Wildlife Area 18 17 !!!!!!!!! 21 O 18 18 17 22 23 15 14 13 16 15 Tophill 24 14 !!!!!!!!! N 19 Wakefield 16 13 18 Giustina Land & Timber 20 Belfort 15 14 13 17 21 Green Mountain !!!!!!!!! 22 16 23 24 15 14 13 18 17 16 Neahkahnie 15 14 13 !!!!!!!!! Beach Manzanita 18 17 16 15 29 28 27 !Nehalem 19 20 19 20 Company P! P 21 22 23 24 21 22 !!!!!!!!! 19 Enright 23 26 25 20 22 24 19 27 30 29 21 23 24 20 L.L "Stub" !!!!!!!!! 28 27 21 26 25 22 23 19 24 20 21 22 23 20 !!!!!!!!! Mohler Stewart State 24 19 21 22 T. -

Outreach Notice

USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region Siuslaw National Forest __________________________________________________________________________________ The Siuslaw National Forest is outreaching, with plans to fill the following seasonal positions for the 2015 summer season. These positions will be advertised through the demo at www.usajobs.gov beginning January 6, 2015 Location Openings Position Contact Siuslaw Fire Zone Up to 6 GS-0462-3/4/5 Forestry Aid (Fire), David Andersen, Engine Captian Hebo, OR Forestry Technician (Fire) (503) 392-5111, 15-TEMP-R60462-4-HSHC-DT-PG [email protected] 15-TEMP-R60462-5-HSHC-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-3-HSHC-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-5-FEO-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-4-ENG-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-3-ENG-DT-PG Siuslaw Fire Zone Up to 8 GS-0462-3/4/5 Forestry Aid (Fire), Aaron Schneider, Crew Captain Waldport, OR Forestry Technician (Fire) (541) 563-8455, 15-TEMP-R60462-4-HSHC-DT-PG [email protected] 15-TEMP-R60462-5-HSHC-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-3-HSHC-DT-PG Siuslaw Fire Zone Up to 6 GS-0462-3/4/5 Forestry Aid (Fire), Jason Monroe, Engine Captain Reedsport, OR Forestry Technician (Fire) (541) 271-6018, 15-TEMP-R60462-4-HSHC-DT-PG [email protected] 15-TEMP-R60462-5-HSHC-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-3-HSHC-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-5-FEO-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-4-ENG-DT-PG 15-TEMP-R60462-3-ENG-DT-PG USDA-Forest Service is an equal opportunity employer and provider. USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region Siuslaw National Forest __________________________________________________________________________________ Location Openings Position Contact Coastal Valley Up to 2 GS-0462-4/5 Forestry Aid (Fire), Roberta Runge, Center Manager, Interagency Comm. -

Ecoregions of Oregon's Coast Range

84 OREGON WILD SUMNER ROBINSON Home to Oregon’s Rainforests Coast Range Ecoregion xtending from the Lower Columbia River south to the California border, Douglas-fir/Western Hemlock forests — the most common forest type in and east from the northeastern Pacific Ocean to the interior valleys of the western Oregon — dominate the interior of the ecoregion. After a disturbance (such as Willamette, Umpqua and Rogue Rivers and to the Klamath Mountains, fire or a blowdown), Douglas-fir will dominate a site for centuries. If no additional Ethe 5.8 million acres in Oregon’s portion of the Coast Range Ecoregion major disturbance occurs, the shade-tolerant western hemlock will eventually overtake rarely exceed 2,500 feet in elevation. Yet these mountain slopes are steep the Douglas-fir and achieve stand dominance on the wettest sites. Grand fir and and interlaced and incised with countless trickles and streams. The highest point, western redcedar are occasionally found in these forests. Red alder and bigleaf maple Marys Peak (4,097 feet), is visible from much of the mid-Willamette Valley. Beyond are common along watercourses, and noble fir can be found at the highest snowy Oregon, the Coast Range Ecoregion extends north into far western Washington (and points in the Coast Range. Toward the southern end of the Oregon Coast Range, includes Vancouver Island in British Columbia) and south to northwestern California. coastal Redwood trees range into Oregon up to twelve miles north of the California In Oregon, only two rivers cross through the Coast Range: the Umpqua and the Rogue. border and are usually found on slopes rather than in river bottoms. -

Boyer-Tillamook Access Road Improvement Project

BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION Boyer-Tillamook Access Road Improvement Project Preliminary Environmental Assessment September 2013 DOE/EA-1941 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Purpose of and Need for Proposed Action 1-1 1.1 Background 1-1 1.2 Need for Action 1-3 1.3 Purposes 1-3 1.4 Public Involvement 1-3 1.4.1 Scoping Comment Period 1-3 1.4.2 Preliminary EA Comment Period 1-4 CHAPTER 2 Proposed Action and Alternatives 2-1 2.1 Proposed Action 2-1 2.1.1 Roads 2-2 2.1.2 Retaining Wall Construction 2-10 2.1.3 Bridge and Arch Pipe Construction 2-11 2.1.4 Staging Areas 2-13 2.1.5 Anticipated Construction Schedule 2-13 2.1.6 Operation and Maintenance 2-13 2.2 No Action Alternative 2-14 2.3 Comparison of Alternatives 2-14 CHAPTER 3 Affected Environment, Environmental Consequences, and Mitigation Measures 3-1 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Land Use, Recreation, and Transportation 3-2 3.2.1 Affected Environment 3-2 3.2.2 Environmental Consequences – Proposed Action 3-7 3.2.3 Mitigation – Proposed Action 3-10 3.2.4 Unavoidable Impacts Remaining After Mitigation 3-10 Boyer-Tillamook Access Road Improvement Project i September 2013 Table of Contents 3.2.5 Cumulative Impacts – Proposed Action 3-10 3.2.6 Environmental Consequences – No Action Alternative 3-11 3.3 Geology and Soils 3-12 3.3.1 Affected Environment 3-12 3.3.2 Environmental Consequences – Proposed Action 3-13 3.3.3 Mitigation – Proposed Action 3-16 3.3.4 Unavoidable Impacts Remaining After Mitigation 3-16 3.3.5 Cumulative Impacts – Proposed Action 3-16 3.3.6 Environmental -

Dreissenid Mussel Rapid Response in the Columbia River Basin: Recommended Practices to Facilitate Endangered Species Act Section 7 Compliance

A native mussel with a cluster of attached zebra mussels found on Beconia Beach on the south basin of Lake Winnipeg. Photo credit: C. Parks, Province of Manitoba. Dreissenid Mussel Rapid Response in the Columbia River Basin: Recommended Practices to Facilitate Endangered Species Act Section 7 Compliance Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission by: Lisa DeBruyckere of Creative Resource Strategies, LLC October 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................................................. 7 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 7 PURPOSE OF THIS MANUAL .......................................................................................................................... 9 SCOPE AND INTENT OF THIS MANUAL .......................................................................................................... 10 QUAGGA AND ZEBRA MUSSELS ................................................................................................................. -

Assessment Report

ASSESSMENT REPORT FEDERAL LANDS IN AND ADJACENT TO OREGON COAST PROVINCE July 1995 We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect ... That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics. - Aldo Leopold Western Oregon Provinces !Ill USFS Lands D BLM Lands D Other Ownerships N 4th Field HUCS j\ ' Study Area Boundary N Provinre Boundary Scale 1:1905720 Mardi 21, 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. INTRODUCTION 1 OVERVIEW OF AREA 2 B. DESCRIPTION OF ASSESSMENT AREA 5 LANDOWNERSHIP 5 NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN 6 C. LARGE-SCALE NATURAL PROCESSES CLIMATE 13 SOIL/CLIMATE ZONES 15 Derivation of Zones 15 Description of Zones 15 NATURAL DISTURBANCE PROCESSES 17 Fire History 18 Development of Disturbance Regime Blocks 19 Disturbance Block Summary 30 LANDSLIDE RISK 33 Debris Slides 33 Deep Seated Slumps and Earthflows 35 Management Implications 35 SOIL PRODUCTIVITY 36 Effects of Wildfire and Timber Harvest Activity 36 Management Implications 37 D. TERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT 39 CURRENT VEGETATION 39 Matrix Vegetation 41 Managed Stands 44 WILDLIFE HABITATS AND SPECIES ASSOCIATED WITH LATE-SUCCESSIONAL FORESTS 45 Amount and Pattern of Late-Successional Forests 45 Dispersal Habitat Analysis 52 Northern Spotted Owls 52 Marbled Murrelets 55 Riparian Reserves 55 Isolated Secure Blocks 59 Botanical Resources 60 Elk Habitat Capability 60 Management Implications for Late-Successional Forest Restoration 62 E. AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 65 WATER QUALITY 65 Effects of Logging 66 Effects of Farming 68 Interagency Coordination Opportunities 68 i - 1 WATER QUANTITY 69 Interagency Management Opportunities 69 FISH DISTRIBUTION 70 FISH HABITAT 71 Riparian Conditions 75 Fish Habitat Needs Within Late-Successional Reserves 78 ODFW Objectives 78 Management Implications 79 F.