The Golden Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WCER Special Economic Zones

Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice WCER Canadian Association Institute Working Academy International of Universities for the Economy Center of National Development and Colleges in Transition for Economic Economy Agency of Canada Reform Special Economic Zones Moscow IET 2007 UDC 332.122 BBC 65.046.11 S78 Special Economic Zones / Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice – Moscow : IET, 2007. – 247 p. : il. – ISBN 9785932552070 Agency CIP RSL Authors: Prihodko S., Volovik N., Hecht A., Sharpe B., Mandres M. Translated from the Russian by Todorov L. Page setting: Yudichev V. The work is concerned with free economic zones classification and basic principles of operation. Foreign experience of free economic zones creation is regarded. Considerable attention is paid to the his tory of free economic zones organization in Russia. The main causes of failures of their implementation are analyzed. At present the work on creation of special economic zones of main types – industrial and production, innovation and technological, tourist and recreation has started in Russia. The main part of the work is devoted to Canadian experience of regional development. JEL Classification: R0, R1. The research and the publication were undertaken in the framework of CEPRA (Consortium for Economic Policy Re search and Advice) project funded by the Canadian Agency for International Development (CIDA). UDC 332.122 BBC 65.046.11 ISBN 9785932552070 5, Gazetny per., Moscow, 125993 Russia Tel. (495) 6296736, Fax (495) 2038816 [email protected], http://www.iet.ru Table of Contents I. Regional Development in Canada..........................................7 1. An Introduction to Regional Development in Canada................7 2. -

BR IFIC N° 2501 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2501 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha: 26.08.2003 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-additioner MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 103018201 AUT 850.000 WIEN AUT 16E23'0" 48N12'0" FX 1 SUP 2 103017022 BEL -

Material Composition and Geochemical Characteristics of Technogenic River Silts E

ISSN 0016-7029, Geochemistry International, 2019, Vol. 57, No. 13, pp. 1361–1454. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2019. Material Composition and Geochemical Characteristics of Technogenic River Silts E. P. Yanin* Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119991 Russia *e-mail: [email protected] Received May 20, 2019; revised June 7, 2019; accepted June 7, 2019 Abstract—The paper discusses the results of many years of studying the material composition and geochem- ical characteristics, conditions, and processes in the formation of technogenic river silts: a new type of mod- ern river sediments formed in riverbeds within the boundaries and zones of influence of industrial–urbanized areas. The article examines the main sources and most important characteristics of technogenic sedimentary material flowing into rivers, as well as the geochemical conditions of technogenic alluvial sedimentation, the morphology and structure of technogenic silts, the extent of their spatial distribution in riverbeds, their grain size characteristics, and mineral and chemical composition. Special attention is paid to analyzing the group composition of organic matter in river sediments and the features of its transformation in pollution zones. The study analyzes the technogenic geochemical associations that form in silts in zones of influence of various impact sources, the features of the concentration and distribution of chemical elements, heavy metal specia- tion, the composition of exchangeable cations in technogenic silts and natural (background) alluvium, and the composition of silt water. Possible secondary transformations of technogenic silts and their significance as a long-term source of pollution of the water mass and hydrobionts are substantiated. -

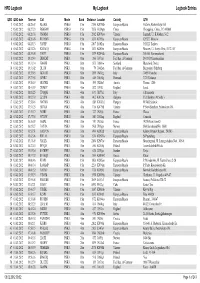

HRD Logbook Logbook Entries My Logbook

HRD Logbook My Logbook Logbook Entries QSO QSO date Time on Call Mode Band Distance Locator Country QTH 105.02.2012 08:28:07 RL6MA PSK63 15m 2150KN98xb European Russia Gukovo, Rostovskaya Obl 205.02.2012 08:27:23 BG8GAM PSK63 15m 7878OL39gm China Chongqing , China , P.C.400060 305.02.2012 08:26:38 US0MM PSK63 15m 2082KN98po Ukraine Lugansk, Ul. K.Marksa, 5-12 405.02.2012 08:26:03 RV3AMV PSK63 15m 1833KO85tu European Russia 129327, Moscow 505.02.2012 08:25:13 UA3RF PSK63 15m 2107LO02rq European Russia 392022, Tambov 605.02.2012 08:24:26 RX3AGQ PSK63 15m 1833KO85ts European Russia Moscow, Ul. Novyi Arbat, 31/12-107 705.02.2012 08:24:00 UA3PI PSK63 15m 1879KO94da European Russia 301650, Novomoskovsk 803.02.2012 19:32:43 DK0KAT PSK31 80m 260JO71ao Fed. Rep. of Germany D-01983 Grossraeschen 903.02.2012 19:31:14 GM4RS PSK31 80m 873IO80vw Scotland Blandford, Dorset 1003.02.2012 19:31:02 DL1OI PSK31 80m 79JO42wn Fed. Rep. of Germany Burgwedel / Fuhrberg 1103.02.2012 19:28:45 IK7GOD PSK31 80m 1269JN81eg Italy 70059 Trani Ba 1203.02.2012 19:27:58 OZ5RZ PSK31 80m 445JO65fq Denmark 2720 Vanloese 1303.02.2012 19:26:49 OE1TRB PSK31 80m 595JN88ef Austria Vienna, 1200 1403.02.2012 18:41:39 2E0WJC PSK63 40m 822IO93ft England Leeds 1503.02.2012 18:18:25 IT9QQM PSK31 40m 1631JM77al Italy Caltanissetta 1603.02.2012 18:12:30 LZ1XM PSK31 40m 1402KN12nr Bulgaria 1320 Bankya (Nr Sofia ) 1703.02.2012 17:58:46 HA7MG PSK31 40m 889KN07cd Hungary H-5008 Szolnok 1803.02.2012 17:51:25 UR7HA PSK31 40m 1710KN79di Ukraine P. -

International Out-Of-Delivery-Area and Out-Of-Pickup-Area Surcharges

INTERNATIONAL OUT-OF-DELIVERY-AREA AND OUT-OF-PICKUP-AREA SURCHARGES International shipments (subject to service availability) delivered to or picked up from remote and less-accessible locations are assessed an out-of-delivery area or out-of-pickup-area surcharge. Refer to local service guides for surcharge amounts. The following is a list of postal codes and cities where these surcharges apply. Effective: January 17, 2011 Albania Crespo Pinamar 0845-0847 3254 3612 4380-4385 Berat Daireaux Puan 0850 3260 3614 4387-4388 Durres Diamante Puerto Santa Cruz 0852-0854 3264-3274 3616-3618 4390 Elbasan Dolores Puerto Tirol 0860-0862 3276-3282 3620-3624 4400-4407 Fier Dorrego Quequen 0870 3284 3629-3630 4410-4413 Kavaje El Bolson Rawson 0872 3286-3287 3633-3641 4415-4428 Kruje El Durazno Reconquista 0880 3289 3644 4454-4455 Kucove El Trebol Retiro San Pablo 0885-0886 3292-3294 3646-3647 4461-4462 Lac Embalse Rincon De Los Sauces 0909 3300-3305 3649 4465 Lezha Emilio Lamarca Rio Ceballos 2312 3309-3312 3666 4467-4468 Lushnje Esquel Rio Grande 2327-2329 3314-3315 3669-3670 4470-4472 Shkodra Fair Rio Segundo 2331 3317-3319 3672-3673 4474-4475 Vlore Famailla Rio Tala 2333-2347 3323-3325 3675 4477-4482 Firmat Rojas 2350-2360 3351 3677-3678 4486-4494 Andorra* Florentino Ameghino Rosario De Lerma 2365 3360-3361 3682-3683 4496-4498 Andorra Franck Rufino 2369-2372 3371 3685 4568-4569 Andorra La Vella General Alvarado Russel 2379-2382 3373 3687-3688 4571 El Serrat General Belgrano Salina De Piedra 2385-2388 3375 3690-3691 4580-4581 Encamp General Galarza -

BR IFIC N° 2500 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2500 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha: 12.08.2003 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-additioner MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 103009455 ALG 698.000 BORDJ EL BAHRI ALG 3E14'0" 36N49'0" BT 1 ADD 2 102087415 -

Mosca È La Città Dei Contrasti

Moscova da: Pavel "KoraxDC" Kazachkov Mosca è la città dei contrasti. Qui trovate sia la semplicità da bohémien che la brillante eleganza: una chiesa ricoperta d’oro del XVI secolo accanto ad una costruzione in vetro degli anni ’90 ed il caviale salato che viene accompagnato dal dolce sjampanskoye. E cosa rappresenta questo spirito meglio di ogni altra cosa che la metropolitana di Mosca? Per pochi rubli potete viaggiare tra le stazioni decorate di lampadari di cristallo e di marmo! jespahjoy Top 5 Palazzo Delle Armaturea al Cremlino Se avete la passione per l’oro, il velluto e le pietre preziose dovete recarvi al Palazzo delle Armature al Cremlino. Qui trov... La Piazza Rossa ed Il Mausoleo ... Circondata dall’edificio del GUM, dal Cremlino e dalla Cattedrale di San Basilio, la Piazza Rossa si mette in mostra. Qui ripo... Galleria Tretiakov da: Ed Yourdon Con le sue 62 sale e 100 000 opere, la Galleria Tretiakov contiene la collezione più grande del mondo di arte russa. Fortunata... Museo Pushkin Di Belle Arti. Un paradiso per chi si interessa di arte. Qui l’arte impressionistica e postimpressionistica è raccolta insieme ad opere più a... da: Chris Aggiornato lunedì 11 maggio 2015 Destinazione: Moscova Data Pubblicazione: 2015-05-11 LA CITTÀ Grande. Indirizzo: Cremlino, ingresso dal Giardino di Alessandro. Telefono: +7 495 921 47 20 Internet: www.kremlin.museum.ru La Piazza Rossa ed Il Mausoleo Di Lenin Circondata dall’edicio del GUM, dal Cremlino e dalla Cattedrale di San Basilio, la Piazza Rossa si mette in mostra. Qui riposa inoltre Lenin nel suo mausoleo. -

The Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Central Russia

THE HOLY NEW MARTYRS AND CONFESSORS OF CENTRAL RUSSIA Vladimir Moss © Copyright, 2008: Vladimir Moss INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 1. HIEROMARTYR MACARIUS, BISHOP OF OREL .......................................5 2. HIEROMARTYR ISIDORE, BISHOP OF MIKHAILOV................................8 3. HIEROMARTYR METROPHANES, BISHOP OF MIKHAILOV...............10 4. HIEROCONFESSOR JOASAPH, ARCHBISHOP OF KRUTITSA.............11 5. HIEROCONFESSOR EUGENE, BISHOP OF KOSTROMA .......................12 6. HIEROMARTYR NICANOR, BISHOP OF NOGINSK ...............................13 7. HIEROCONFESSOR BASIL, BISHOP OF SUZDAL ...................................14 8. HIEROCONFESSOR THEODORE, BISHOP OF MOSALSK .....................15 9. HIEROCONFESSOR BORIS, ARCHBISHOP OF RYAZAN ......................17 10. HIEROCONFESSOR NICHOLAS, BISHOP OF VYAZNIKI....................19 11. HIEROCONFESSOR AGATHANGELUS, METROPOLITAN OF YAROSLAVL.........................................................................................................20 12. HIEROCONFESSOR NICHOLAS, BISHOP OF VETLUGA ....................26 13. HIEROMARTYR MAXIMUS, BISHOP OF SERPUKHOV .......................31 14. HIEROCONFESSOR MICAH, BISHOP OF KALUGA .............................53 15. HIEROMARTYR BENJAMIN, BISHOP OF RYBINSK..............................56 16. HIEROCONFESSOR AMBROSE OF MSTER .............................................61 17. HIEROCONFESSOR JOB, BISHOP OF MSTER .........................................62 -

Investment Passport of Taldomsky Urban District

Investment Passport of Taldomsky Urban District 2019 Dear friends! It is a pleasure for me to introduce to you Taldomsky district, the northmost territory of Moscow region with a very high potential. Consumer power together with economic and social capacity of the territory are ambitious and demand strong management decisions and effective investment policy. Taldomsky district is ready to broaden diversified business contacts based on true equality and respect of mutual interests. We confirm the seriousness of our intentions not only by the objective analysis of the territory’s basic opportunities, but also by the readiness to support an investment project all the way through, to get through the most difficult launching phase and to create comfortable environment for establishment and development of the district’s new economic entity. The general principles on which we rely on in our important and highly demanded work are the development of investment friendly environment and a real help in practice rather than in words. I am sure that this Investment Passport will attract your interest and inspire you to take further actions. I will give every possible help and support and will be very pleased to work together on the territory of Taldomsky district! Head of Taldomsky district Vladislav Yudin Brief historical digression Taldomsky district is the northmost district of Moscow region. It was mentioned for the first time in 1677. That time it was a small village with 7 households. Since the 17th century Taldom has come through a growth of shoe manufacturing in the town and villages. According to the encyclopaedical dictionary, published in 1901, the village of Taldom was mentioned as ―a centre of shoe district, the capital of the shoe empire‖. -

International Out-Of-Delivery-Area and Out-Of-Pickup-Area Surcharges

INTERNATIONAL OUT-OF-DELIVERY-AREA AND OUT-OF-PICKUP-AREA SURCHARGES International shipments (subject to service availability) delivered to or picked up from remote and less-accessible locations are assessed an out-of-delivery area or out-of-pickup-area surcharge. Refer to local service guides for surcharge amounts. The following is a list of postal codes and cities where these surcharges apply. Effective: September 19, 2011 Albania Coronel Pringles Pigue 0845-0847 3254 3612 4380-4385 Berat Crespo Pinamar 0850 3260 3614 4387-4388 Durres Daireaux Puan 0852-0854 3264-3274 3616-3618 4390 Elbasan Diamante Puerto Santa Cruz 0860-0862 3276-3282 3620-3624 4400-4407 Fier Dolores Puerto Tirol 0870 3284 3629-3630 4410-4413 Kavaje Dorrego Quequen 0872 3286-3287 3633-3641 4415-4428 Kruje El Bolson Rawson 0880 3289 3644 4454-4455 Kucove El Durazno Reconquista 0885-0886 3292-3294 3646-3647 4461-4462 Lac El Trebol Retiro San Pablo 0909 3300-3305 3649 4465 Lezha Embalse Rincon De Los Sauces 2312 3309-3312 3666 4467-4468 Lushnje Emilio Lamarca Rio Ceballos 2327-2329 3314-3315 3669-3670 4470-4472 Shkodra Esquel Rio Grande 2331 3317-3319 3672-3673 4474-4475 Vlore Fair Rio Segundo 2333-2347 3323-3325 3675 4477-4482 Famailla Rio Tala 2350-2360 3351 3677-3678 4486-4494 Andorra* Firmat Rojas 2365 3360-3361 3682-3683 4496-4498 Andorra Florentino Ameghino Rosario De Lerma 2369-2372 3371 3685 4568-4569 Andorra La Vella Franck Rufino 2379-2382 3373 3687-3688 4571 El Serrat General Alvarado Russel 2385-2388 3375 3690-3691 4580-4581 Encamp General Belgrano Salina -

Russian Market Internationalization: Ceramifor Case Study

Internship Report Master in International Business RUSSIAN MARKET INTERNATIONALIZATION: CERAMIFOR CASE STUDY Aliaksandr Lasianok Leiria, May 2017 Internship Report Master in International Business RUSSIAN MARKET INTERNATIONALIZATION: CERAMIFOR CASE STUDY Aliaksandr Lasianok Internship Report developed under the supervision of Phd Vitor Ferreira, professor at the School of Technology and Management of the Polytechnic Institute of Leiria and co- supervision of Paula Cardoso co-supervisor, commercial coordinator at the CERAMIFOR. Leiria, May 2017 Acknowledgements I’m grateful to my curator and professor of IPL Vitor Hugo Ferreira for his patience to my mistakes, support and clear guidance of a working process. Would like to thank all the CERAMIFOR’s team for a friendly reception, warm environment and helpfulness. Special gratitude goes to the managing director Bruno Bras for provision of opportunities of exhibition attendance, what I liked so much. Additionally, I want to acknowledge the company’s curator Paula Cardoso for her efforts and care of my adaptation in the company and all advices done. Thanks for all your encouragement! ii Resumo (in portuguese) O desenvolvimento das tecnologias tornou o mundo "mais pequeno", promovendo o surgimento de conexões entre todas as partes do mundo. Sob tais condições as empresas tendem a envolver o processo de internacionalização expandindo-se para diferentes mercados, empurradas por vários objetivos e motivos. Os negócios e empresas internacionais têm tentado desenvolver uma estrutura ideal que permita às empresas evitar riscos e implementar a estratégia inicial mais apropriada. Entre as perspectivas mais populares podem ser destacadas: Resource based view, Transaction costs view, Institutional view, Uppsala model etc. O trabalho baseia-se no estudo do caso da empresa CERAMIFOR, um fabricante português de equipamentos de indústria cerâmica e tratamento térmico. -

Febrer 2019 Abasha

Febrer 2019 Abasha ..... H-10 Al Hoceima ..... J-2 Almus ..... I-9 Åbenrá ..... E-5 Alacant ..... I-3 Alosno ..... I-2 Aberaeron ..... E-3 Alaka ..... I-9 Alovo ..... D-10 Aberdeen ..... D-4 Alanya ..... J-9 al-Qaryatayn ..... J-10 Abertillery ..... E-3 Alapli ..... I-8 Altamura ..... I-6 Åbo ..... D-7 Alashchevskaya ..... F-10 Altenholz ..... E-5 Aboyne ..... D-4 Alatyr ..... D-10 Alüksne ..... D-7 Abu ad Duhur ..... J-10 Alba ..... H-5 Alushta ..... H-9 Abu Kemal ..... J-10 Alba Iulia ..... G-7 Ålvdalen ..... C-6 Acate ..... J-6 Albacete ..... I-3 Alvito ..... H-1 Achames ..... J-7 Albarracín ..... H-3 Ålvsbyn ..... B-7 Acri ..... I-6 Albertville ..... G-4 Alyth ..... D-4 Adana ..... J-9 Albi ..... H-4 Alytus ..... E-7 Adapazari ..... I-8 Alborg ..... D-5 Alzira ..... I-3 Adazi ..... D-7 Albox ..... I-2 Amaliada ..... J-7 Ademuz ..... H-3 Alburquerque ..... H-2 Amantea ..... I-6 Adiyaman ..... I-10 Alcacér do Sal ..... H-1 Amasra ..... H-9 Adjud ..... G-8 Alcalá de Henares ..... H-3 Amasya ..... I-9 Adrano ..... J-5 Alcamo ..... J-5 Amberes ..... F-4 Adria ..... H-5 Alcañíz ..... H-3 Ambleside ..... E-4 Aegio ..... J-7 Alcobaça ..... H-1 Amfissa ..... J-7 Afipskiy ..... G-10 Alcobendas ..... H-2 Amhem ..... F-5 Aflou ..... J-3 Alcoi ..... I-3 Amiens ..... F-4 Afrin ..... J-10 Alcora, l’ ..... I-3 Åmli ..... D-5 Afsin ..... I-9 Alcorcón ..... H-2 Amposta ..... H-3 Afyon ..... I-8 Alcorisa ..... H-3 Amsterdam ..... F-4 Agadir ..... J-1 Ale ..... D-6 Amvrosiivka ..... G-9 Agara ..... H-10 Alekhnovshchina ....