Effective School Characteristics and Student Achievement Correlates As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondarystudentparen Thandbook 2 0

SECONDARY STUDENT PARENT HANDBOOK 2020-21 Title 1 SECONDARY STUDENT PARENT HANDBOOK 2020-21 Table of Contents Message from the Superintendent Page 7 Message from the Secondary Principal Page 8 Contacting the School Page 9 Telephone Contact List Secondary Faculty Email Addresses Accounts Office Secondary Quick Calendar 2018-19 Understanding Lahore American School Page 11 LAS Mission LAS Beliefs LAS Profile of Graduates Joining LAS Page 14 Admissions Grade Placement Transfer of High School Credits Transfer from Other National Systems Transfer From Schools with Different Calendars A New Student’s First Day at LAS The LAS Campus Page 15 Facilities Cafeteria Swimming Pool Media Resource Center School Store WiFi Water Campus Security and Emergency Procedures Page 17 Traffic Identification Visitors Surveillance Student Pickup under Extraordinary Circumstances Safety Drills Fire Drill Procedure Duck and Cover Drill Procedure Lockdown Procedure 2 SECONDARY STUDENT PARENT HANDBOOK 2020-21 Code of Conduct- Parents For Your Child’s Safety Page 20 For Your Child’s Health For Your Child’s Success in School For Your Child’s Moral Development For Your Child’s Belongings Administration of Over-the-Counter Medications at LAS Communication Between LAS and Home Channels of Communication Staying Informed Parent-Teacher-Student Conferences Notification of Student Withdrawals Code of Conduct-Students Page 25 Student Rights Student Responsibilities Daily Life at School Page 29 School Hours Class Schedule Bell Schedule Required Supplies Print Resources Technology -

Teacher Education Policies and Programs in Pakistan

TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education - Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang Two significant effects of globalization around the world are the decentralization and liberalization of systems, including education services. In 2000, the Pakistani Government brought major higher education liberalization and expansion reforms by encouraging market approaches based on self-financed programs. These approaches have been particularly important in the area of teacher education and development. The Pakistani Government data reports (AEPAM Islamabad) on education show vast growth in market-model off-campus (open and distance) post-baccalaureate teacher education programs in the last fifteen years. Many academics and scholars have criticized traditional off-campus programs for their low quality; new policy reforms in 2009, with the support of USAID, initiated the four-year honors program, with the intention of phasing out all traditional programs by 2018. However, the new policy still allows traditional off-campus market-model programs to be offered. This important policy reform juncture warrants empirical research on the effectiveness of traditional programs to inform current and future policies. Thus, this study focused on assessing the worth of traditional and off-campus programs, and the effects of market approaches, on the implementation of traditional post-baccalaureate teacher education programs offered by public institutions in a southern province of Pakistan. -

Secondary Student Parent Handbook 2021-22

Secondary Student Parent Handbook 2021-22 LAHORE AMERICAN SCHOOL Table of Contents MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT PAGE 3 | MESSAGE FROM THE SECONDARY PRINCIPAL PAGE 5 | MESSAGE FROM THE SECONDARY ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL/CURRICULUM COORDINATOR PAGE 6 | CONTACTING THE SCHOOL PAGE 7 | UNDERSTANDING LAHORE AMERICAN SCHOOL PAGE 9 | JOINING LAS PAGE 13 | THE LAS CAMPUS PAGE 15 | CAMPUS SECURITY AND EMERGENY PROCEURES PAGE 17 | CODE OF CONDUCT: PARENTS PAGE 20 | CODE OF CONUCT PAGE 22 | EXPECTATIONS OF LAS STUDENTS PAGE 25 | EXPECTATIONS OF LAS PARENTS AND GUARDIANS PAGE 26 | DAILY LIFE AT SCHOOL PAGE 30 | STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES PAGE 36 | LAS ACADEMICS: HIGH SCHOOL PAGE 39 | LAS ACADEMICS : MIDDLE SCHOOL PAGE 43 | ASSESSMENT AND REPORTING PAGE 45 | STANDARDIZED TESTS AT LAS PAGE 49 | ACADEMIC STATUS: HONORS AND AWARDS PAGE 50 | ACADEMIC STATUS : WARNING AND PROBABTION PAGE 51 | STUDENT ACADEMIC EXPECTATIONS AND CONSEQUENCES PAGE 52 | STUDENT ATTENDANCE EXPECTATIONS PAGE 53 | STUDENT BEHAVIORAL EXPEPECTATIONS AND DISCIPLINE PAGE 55 | STUDENT LIFE AND ACTIVITIES PAGE 58 | STUDENT GOVERNMENT AND ORGANIZATIONS PAGE 60 | SAISA PAGE 63 | SAISA CALENDAR PAGE 66 | CONTACT INFORMATION PAGE 66 | IMPORTANT FORMS PAGE 67| Message from the Superintendent A warm welcome to the 2021/2022 school year to all our LAS secondary families. The secondary department at Lahore American School is student- centered, where our learners come first. We strive to provide an educational platform for learners of every skill level. We ensure both inclusion, and diversity, throughout our secondary department through a tiered curriculum program available to all learners. Through our specialized learning support program, we’ve developed a curriculum that provides additional assistance to students with special needs. -

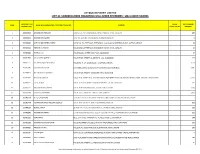

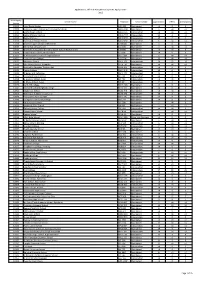

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. -

Program of Studies – Message from the Principal

Program of Studies 2017-2018 Program of Studies – Message from the Principal Dear LAS Student, Our goals of the secondary program at Lahore American School are twofold. The first goal is for you, the student, to receive acceptance letters from the universities to which you apply. However this is just the beginning. Our second goal is for you to successfully complete the course of study at the university you decide to attend. In order to receive those acceptance letters you must accomplish five important things. You must write a solid college application essay You need strong letters of recommendation from your teachers and counselor. You must have good scores in your standardized testing such as the SAT. You need to show leadership in activities, athletics, organizations, and projects. You must demonstrate a commitment to learning and stretch yourself academically in a rigorous academic program The Lahore American School’s Program of Studies is designed to provide each student with a rigorous program that will accomplish the two goals. Firstly, it will show admissions officials at your selected universities that you have challenged yourself academically. Secondly, by successfully completing a rigorous academic program, you are academically prepared for the challenges of university study. The descriptions provided in this document will help you answer the following important questions: Am I choosing courses that are appropriate for my abilities, interests and career plans? Am I choosing courses that will challenge my abilities? Am I choosing courses that fulfill LAS graduation requirements? Am I choosing courses that qualify me for the universities I wish to attend? Am I choosing a program of study that allows time for extra-curricular activities? It is important to remember to seek information from a variety of sources. -

Green Region (Punjab) 33 Cash Prize Winner

RESULTS Green Region (Punjab) 33 Cash Prize Winner 03 National Winners 47 Teacher’s Award of Excellence 215 Winners 06 National Winners Children with Special Needs Prize of Honor Selected for Exhibitions 120 Winners of 315 ArtBeat Special Studio Workshop Award Winners Jury & Selection R.M. Naeem Painter and Teacher, National College of Arts Abdul Jabbar Gull Sculptor and Painter Sadaf Naeem Painter and Lecturer, Kinnaird College Sajjad Akram Visual Artist and Teacher National College of Arts CASH PRIZE WINNERS Green Region Prizes (Punjab) Age Group A: (4-9 years) 1st Prize: 7,000 Rs. Class School M.Haider Awan KG TNS Beaconhouse DHA Lahore 2nd Prize: 5,000 Rs. Class School Sarah Mueed Prep-A Lahore GraMMar School 31 FCC Lahore 3rd Prize: 3,000 Rs. Class Class Zahrah Prep Orange APS Garrison Junior Abid Majeed Road Lahore Age Group B: (10-14 years) 1st Prize: 7,000 Rs. Class School Aroosh 4-A FatiMa Fertilizer School Sadiqabad 2nd Prize: 5,000 Rs. Class School Khadeeja IMran VII Beaconhouse School SysteM Bahawalpur 3rd Prize: 3,000 Rs. Class Class Maheen Zohaib V-Red Beaconhouse School SysteM Girls PriMary Johar Town Lahore Age Group C: (15-18 years) 1st Prize: 7,000 Rs. Class School Mina SalMan A-Level The City School Ravi CaMpus Lahore 2nd Prize: 5,000 Rs. Class School Syeda MaiMoona TabassuM 11 Independent Artist Lahore 3rd Prize: 3,000 Rs. Class Class Maya Zaidi A2 Independent Artist Lahore National Prizes For CHildren WitH Special Needs 6 Prizes of 7,000 Rs. Each for children with special needs Mazhar Abbas Govt Special Educaiton Center -

Full Name Jobtitle Institution Country Kamal Abdel-‐Nour President Ibn

Full Name JobTitle Institution Country Kamal Abdel-Nour President Ibn Khuldoon National School Bahrain Abdul Nasser Business/Finance Universal American School UAE Browning Curriculum/P.D. Al Bayan Bilingual School Kuwait Saleh Abdullah Salem Al MekhleF Board Member/Trustee Kuwait Bilingual School Kuwait Mohammed Abdulmajeed Board Member/Trustee The American International School oF Muscat Oman Sana Abiad Other International Schools Group Saudi Arabia Roula Raidan AbiFaker Teacher Leader/Dept.Head American School oF Dubai UAE Carlos Aboumrad Other Bahrain Bayan School Bahrain Jeries Abu Al Etham Other Friends School Palestine Karim Abu Haydar Principal American Community School Lebanon Mohamed Hafez Mousa Abu-Lebdeh Teacher Leader/Dept.Head Dhahran Ahliyya Schools Saudi Arabia Baria Abu Zein Principal Al Najah Private School UAE Walid Abushakra Head oF School/Institution Educational Services Overseas Limited (ESOL) Egypt Tammam Abushakra Other Educational Services Overseas Limited (ESOL) Egypt Bassam Abushakra Head oF School/Institution Educational Services Overseas Limited (ESOL) Egypt Mr. JohnEric Advento Principal American School oF Dubai UAE Dana K. Adwan Business/Finance King's Academy Jordan Maisae AFFour ES Principal Ibn Khuldoon National School Bahrain Fazna Ahmed Board Member/Trustee The Overseas School oF Colombo Sri Lanka Sajeda Akbarally Board Member/Trustee The Overseas School oF Colombo Sri Lanka Ala-din Al-afghani Principal Kuwait bilingual school kuwait Lana Al-Aghbar Principal American School oF Doha Qatar Maryam Ahmed Naser Al Ali Other Abu Dhabi Education Council UAE Rashed Al Doulab Other International Schools Group Saudi Arabia Dahi Laili Al Fadhli ChieF Executive OFFicer Sama Educational Co KSCC-Kuwait Kuwait Feda Al Khatib Board Member/Trustee Advanced Learning Schools Saudi Arabia Amal Mustafa Al-Minawai Principal American Baccalaureate School Kuwait Alaa Mohammed Al Mumtan Business/Finance Dhahran Ahliyya Schools Saudi Rabia Maha Al Romaihi Asst. -

ED318701.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 318 70]. SP 032 197 AUTHOR Bernardi, Ray D. TITLE Teaching in Other Countries. An Overview of the Opportunities for Teachers from the U.S.A. PUB DATE 2 Dec 89 NOTE 50p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Vocational Association (Orlando, FL, December 1-5, 1989). Printed on colored stock, therefore some lists may not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Differences; *Culture Conflict; Foreign Countries; *Overseas Employment; *Teacher Exchange Programs; *Teaching (Occupation); Teaching Conditions; Vocational Adjustment ABSTRACT Suggestions are made for teachers considering teaching abroad. The following topics are covered:(1) problems encountered In working in a foreign environment, e.g., culture shock; (2) general considerations in making the decision to teach overseas; (3) steps to follow when seeking an overseas position;(4) overseas employment opportunities with the Department of Defense Dependents Schools;(5) overseas placement services for educators; (6) The University of Maryland Overseas Program;(7) international jobs--teaching; (8) an alphabetical list of 225 Overseas American Community Schools; (9) answers to questions regarding recruitment for international schools; and (10) the Fulbright Teacher Exchange Program. (JD) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** '"""e""""""'"'"'""""'"""'"W""'"'""eloW.I::M.Inxwn"."..%NI1rlswmlndW"""W"...""''"'"":'""w".'"'"""WasIWsll'"'""'"".Ow1000 MINIFIffilowympomn. .0. IN ....romemommag .111 TEACHING WY M/6 =wsn.O OTHER 0.0.11.1~0 Irenworreffir e.merwrame 610111.0. 11........ 1.101116 ....... .11......... ........INIMOIMPole ....... 40... wirdesearer 11 7'.":"=....... COUNTRIES 01.....0...10.4. -

20Th November 2015 Dear Request for Information Under the Freedom

Governance & Legal Room 2.33 Services Franklin Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street Information Management London and Compliance SE1 9NH Tel: 020 7848 7816 Email: [email protected] By email only to: 20th November 2015 Dear Request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (“the Act”) Further to your recent request for information held by King’s College London, I am writing to confirm that the requested information is held by the university. Some of the requested is being withheld in accordance with section 40 of the Act – Personal Information. Your request We received your information request on 26th October 2015 and have treated it as a request for information made under section 1(1) of the Act. You requested the following information. “Would it be possible for you provide me with a list of the schools that the 2015 intake of first year undergraduate students attended directly before joining the Kings College London? Ideally I would like this information as a csv, .xls or similar file. The information I require is: Column 1) the name of the school (plus any code that you use as a unique identifier) Column 2) the country where the school is located (ideally using the ISO 3166-1 country code) Column 3) the post code of the school (to help distinguish schools with similar names) Column 4) the total number of new students that joined Kings College in 2015 from the school. Please note: I only want the name of the school. This request for information does not include any data covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.” Our response Please see the attached spreadsheet which contains the information you have requested. -

TITLE AVAILABLE from the Office of Overseas Schools in Fiscal Year 1985. OW

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 274 623 SO 017 663 TITLE Overseas American Sponsored Elementary and Secondary Schools Assisted by the U.S. Department of State. INSTITUTION Department of State, Washington, D.C. Office of Overseas Schools. PUB DATE Jan 86 NOTE 35p.; Small print may affect legibility of document. AVAILABLE FROMOffice of Overseas Schools (A/OS), Room 234, SA-6, U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC 20520. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage., DESCRIPTORS *Educational FacilitiGs; *Elementary Schools; Elementary Secondary Education; *Foreign Countries; Guides; Reference Materials; *School Location; *Secondary Schools ABSTRACT The Office of Overseas Schools of the United States Department of State provides assistance to independent overseas schools which meet certain legislative criteria. The basic purposes of the assistance are to ensure that adequate educational opportunities exist for the dependents of government personnel stationed overseas, and to encourage and assist schools which demonstrate United States educational philosophy and practice within the countries in which they are located. The directory covers five geographic areas (Europe, Africa, Near East and South Asia, East Asia, and American Republics) with specific geographic locations listed alphabetically under each main area. The name and title of each school's chief administrator and the name, address, and telephone number of the school are given under each location listed. Also listed are the enrollment, the grades included in the regular program, and whether supervised correspondence work is offered at certain grade levels. The lists iTtclude the names and addresses of overseas schools which received direct or indirect assistance from the Office of Overseas Schools in Fiscal Year 1985. -

2012 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2012 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <4 0 0 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent <4 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 15 4 4 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 6 <4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained 4 <4 <4 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 0 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <4 0 0 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 6 <4 <4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 15 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 26 13 10 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 <4 <4 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 0 0 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 18 6 5 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 4 <4 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <4 0 0 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 <4 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 7 4 4 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <4 0 0 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <4 0 0 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <4 <4 0 10045 Wellington College, -

Annual Report 2018 3 NOTICE of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

INSPIRING GROWTH “RESPONSIBLY” Built on the pillars of sustainable development, exploration and social responsibility for the benefit of all, the Oil & Gas Development Company Limited has a storied legacy of providing the nation with a wealth of resources. As a responsible entity, we take it upon ourselves to uplift our society and contribute to the betterment of our people across all our operations. This year’s report is a reflection of our intent to spur development and growth in Pakistan and add value through our social responsibility programs. For the people of this great nation, we envision a future of prosperity and ambition that will carry on for generations to come. CONTENTS Product Portfolio Geographical Presence Review Report to the Members 2 and Net Saleable Production 36 81 on the Statement of Compliance Product-wise Contribution Six Years Performance Statement of Compliance 3 in Net Sales 38 82 Notice of Annual General Vertical and Horizontal Analysis Independent Auditors’ Report to 4 Meeting 41 91 the Members 6 Calendar of Major Events 42 Statement of Value Addition 98 Statement of Financial Position 8 Highlights of the Year 43 DuPont Analysis 100 Statement of Profit or Loss Vision and Mission Analysis of Variation in Results Statement of Comprehensive 10 Core Values and Goals 43 Reported in Interim Reports 101 Income 12 Code of Conduct 44 Share Price Sensitivity Analysis 102 Statement of Changes in Equity 14 Corporate Information 45 Investor Relations 103 Statement of Cash Flow Core Management Team Relationship and Engagement