The Walking Dead in Medieval England: Literary and Archaeological Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ug Abuse and Dependence

Edited by Foxit PDF Editor Copyright (c) by Foxit Software Company, 2004 For Evaluation Only. (Modified) FORENSIC MEDICINE Learning Objectives At the end of the course in Forensic Medicine, the learner shall be able to: - 1. Identify, examine and prepare report or certificate in medico-legal cases/situations in accordance with the law of land. 2. Perform medico-legal postmortem examination and interpret autopsy findings and results of other relevant investigations to logically conclude the cause, manner and time since death. 3. Be conversant with medical ethics, etiquette, duties, rights, medical negligence and legal responsibilities of the physicians towards patients, profession, society, state and humanity at large. 4. Be aware of relevant legal / court procedures applicable to the medico-legal/medical practice. 5. Preserve and dispatch specimens in medico-legal / postmortem cases and other concerned materials to the appropriate Government agencies for necessary examination. 6. Manage medico-legal implications, diagnosis and principles of therapy of common poisons. 7. Be aware of general principles of environmental, occupational and preventive aspects of toxicology. Course contents Must Desirable know to know Forensic Medicine (Forensic Pathology) 1. Definition of Forensic Medicine and Medical Jurisprudence. √ 2. Courts in India and their powers: Supreme Court, High Court, √ Sessions Court, Additional Sessions Court, Magistrate’s Courts. 3. Court procedures: Summons, conduct money, oath, affirmation, √ perjury, types of witnesses, recording of evidence, conduct of doctor in witness box, 4. Medical certification and medico-legal reports including dying √ declaration. 5. Death : a) Definition, types; somatic, cellular and brain – death. √ b) Sudden natural and unnatural deaths. √ c) Suspended animation. √ 6. -

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Saxon Newsletter-Template.Indd

Saxon Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society No. 50 / January 2010 (© Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) Hoards of Gold! The recovery of hundreds of 7th–8th century objects from a field in Staffordshire filled the newspapers when it was announced by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) at a press conference on 24 September. Uncannily, the first piece of gold was recovered seventy years to the day after the first gold artefact was uncovered at Sutton Hoo on 21 July 1939.‘The old gods are speaking again,’ said Dr Kevin Leahy. Dr Leahy, who is national finds advisor on early medieval metalwork to the PAS and who catalogued the hoard, will be speaking to the SHS on 29 May (details, back page). Current Archaeology took the hoard to mark the who hate thee be driven from thy face’. (So even launch of their ‘new look’ when they ran ten pages this had a military flavour). of pictures in their November issue [CA 236] — “The art is like Sutton Hoo — gold with clois- which, incidentally, includes a two-page interview onée garnet and fabulous ‘Style 2’ animal interlace with our research director, Professor Martin on pommels and cheek guards — but maybe a Carver. bit later in date. This and the inscription suggest Martin tells us, “The hoard consists of 1,344 an early 8th century date overall — but this will items mainly of gold and silver, although 864 of probably move about. More than six hundred pho- these weigh less than 3g. The recognisable parts of tos of the objects can be seen on the PAS’s Flickr the hoard are dominated by military equipment — website. -

DOA Stories and Questions

Name:_________________ Hour:_______ Dead On Arrival Articles Getting Rid of the Body !Criminals don"t like to leave behind evidence, although they usually do. In a murder, the primary bit of evidence is obviously the body. Sometimes a murderer attempts to completely destroy the body of a victim, reasoning that no body means no conviction. Not true -- convictions have been obtained even when no body is found. Regardless, destroying a body is no easy task. Fire seems to be the favorite tool of murderers looking to cover their tracks, but its almost never successful. Short of a crematorium, creating a fire that burns hot enough and long enough to destroy a human corpse is nearly impossible. !Another favorite is quicklime, which murderers often have seen used in the movies. Knowing the chemistry behind it might make them think twice about this one. Quicklime is calcium oxide. When it contacts water, as it often does in burial sites, it reacts with the water to make calcium hydroxide, also known as slaked lime. This corrosive material may damage the surface of the corpse, but the heat produced from its activity kills many of the putrefying bacteria and dehydrates the body, thereby preventing decay and promoting mummification. Thus, the use of quicklime actually may help preserve the body. !Acids also are commonly used by ill-informed criminals hoping to dissolve the body, which is not only difficult but extremely hazardous. Acids that are powerful enough to dissolve a body exist, but they require a great deal of time to complete the task. -

Trilingualism and National Identity in England, from the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2015 Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century Christopher Anderson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christopher, "Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century" (2015). WWU Graduate School Collection. 449. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/449 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three Languages, One Nation Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century By Christopher Anderson Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School Advisory Committee Chair, Dr. Peter Diehl Dr. Amanda Eurich Dr. Sean Murphy Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

1.1 Biblical Wisdom

JOB, ECCLESIASTES, AND THE MECHANICS OF WISDOM IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY by KARL ARTHUR ERIK PERSSON B. A., Hon., The University of Regina, 2005 M. A., The University of Regina, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2014 © Karl Arthur Erik Persson, 2014 Abstract This dissertation raises and answers, as far as possible within its scope, the following question: “What does Old English wisdom literature have to do with Biblical wisdom literature?” Critics have analyzed Old English wisdom with regard to a variety of analogous wisdom cultures; Carolyne Larrington (A Store of Common Sense) studies Old Norse analogues, Susan Deskis (Beowulf and the Medieval Proverb Tradition) situates Beowulf’s wisdom in relation to broader medieval proverb culture, and Charles Dunn and Morton Bloomfield (The Role of the Poet in Early Societies) situate Old English wisdom amidst a variety of international wisdom writings. But though Biblical wisdom was demonstrably available to Anglo-Saxon readers, and though critics generally assume certain parallels between Old English and Biblical wisdom, none has undertaken a detailed study of these parallels or their role as a precondition for the development of the Old English wisdom tradition. Limiting itself to the discussion of two Biblical wisdom texts, Job and Ecclesiastes, this dissertation undertakes the beginnings of such a study, orienting interpretation of these books via contemporaneous reception by figures such as Gregory the Great (Moralia in Job, Werferth’s Old English translation of the Dialogues), Jerome (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten), Ælfric (“Dominica I in Mense Septembri Quando Legitur Job”), and Alcuin (Commentarius Super Ecclesiasten). -

Death - the Eternal Truth of Life

© 2018 JETIR March 2018, Volume 5, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) DEATH - THE ETERNAL TRUTH OF LIFE The „DEATH‟ that comes from the German word „DEAD‟ which means tot, while the word „kill‟ is toten, which literally means to make dead. Likewise in Dutch ,‟DEAD‟ is dood and “kill” is doden. In Swedish, “DEAD” is dod and „Kill‟ is doda. In English the same process resulted in the word “DEADEN”, where the suffix “EN” means “to cause to be”. We all know that the things which has life is going to be dead in future anytime any moment. So, the sentence we know popularly that “Man is mortal”. The sources of life comes into human body when he/she is in the womb of mother. The active meeting of sperm and eggs, it create a new life in the woman‟s overy, and the woman carried the foetus with 10 months and ten days to given birth of a new born baby . When the baby comes out from the pathway of the vagina of his/her mother, then his/her first cry is depicted that the new born baby is starting to adjustment of of the newly changing environment . For that very first day, the baby‟s survivation is rairtained by his/her primary environment. But the tendency of death is started also. In any time of any space the human baby have to accept death. Not only in the case of human being, but the animals, trees, species, reptailes has also the probability of death. The above mentioned live behind are also survival for the fittest. -

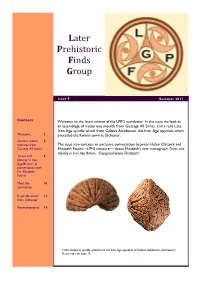

LPFG Newsletter Issue 9

Later Prehistoric Finds Group Issue 9 Summer 2017 Contents Welcome to the latest edition of the LPFG newsletter. In this issue we look at an assemblage of mysterious moulds from Gussage All Saints, and a rare Late Iron Age spindle whorl from Calleva Atrebatum, the Iron Age oppidum which Welcome 2 preceded the Roman town at Silchester. Curious mould 3 matrices from The issue also contains an exclusive conversation between Helen Chittock and Gussage All Saints Elizabeth Foulds—LPFG treasurer—about Elizabeth’s new monograph, Dress and Identity in Iron Age Britain. Congratulations Elizabeth! ‘Dress and 6 Identity in Iron Age Britain’: A conversation with Dr. Elizabeth Foulds Meet the 10 committee A spindle whorl 12 from Silchester Announcements 14 Half a biconical spindle wheel from the Iron Age oppidum of Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). Read more on page 12. Page 2 Welcome The Later Prehistoric Finds Group was established in 2013, and welcomes anyone with an interest in prehistoric artefacts, especially small finds from the Bronze and Iron Ages. We hold an annual conference and produce two newsletters a year. Membership is currently free; if you would like to join the group, please e-mail [email protected]. We are a new group, and we are hoping that more researchers interested in prehistoric artefacts will want to join us. The group has opted for a loose committee structure that is not binding, and a list of those on the steering committee, along with contact details, can be found on our website: https://sites.google.com/site/laterprehistoricfindsgroup/home. Anna Booth is the current Chair, and Dot Boughton is Deputy. -

Exploring the Potential of the Strontium Isotope Tracing System in Denmark

Danish Journal of Archaeology, 2012 Vol. 1, No. 2, 113–122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2012.760889 Exploring the potential of the strontium isotope tracing system in Denmark Karin Margarita Frei* Danish Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, CTR, SAXO Institute, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark (Received 1 October 2012; final version received 14 November 2012) Migration and trade are issues important to the understanding of ancient cultures. There are many ways in which these topics can be investigated. This article provides an overview of a method based on an archaeological scientific methodology developed to address human and animal mobility in prehistory, the so-called strontium isotope tracing system. Recently, new research has enabled this methodology to be further developed so as to be able to apply it to archaeological textile remains and thus to address issues of textile trade. In the following section, a brief introduction to strontium isotopes in archaeology is presented followed by a state-of-the- art summary of the construction of a baseline to characterize Denmark’s bioavailable strontium isotope range. The creation of such baselines is a prerequisite to the application of the strontium isotope system for provenance studies, as they define the local range and thus provide the necessary background to potentially identify individuals originating from elsewhere. Moreover, a brief introduction to this novel methodology for ancient textiles will follow along with a few case studies exemplifying how this methodology can provide evidence of trade. The strontium isotopic system the strontium isotopic signatures are not changed in – from – Strontium is a member of the alkaline earth metal of a geological perspective very small time spans, due to Group IIA in the periodic table. -

The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the Family, the Fief and the Feudal Monarchy*

© K.S.B. Keats-Rohan 1991. Published Nottingham Mediaeval Studies 36 (1992), 42-78 The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the family, the fief and the feudal monarchy* In memoriam R.H.C.Davis 1. The Problem (i) the non-Norman Conquest Of all the available studies of the Norman Conquest none has been more than tangentially concerned with the fact, acknowledged by all, that the regional origin of those who participated in or benefited from that conquest was not exclusively Norman. The non-Norman element has generally been regarded as too small to warrant more than isolated comment. No more than a handful of Angevins and Poitevins remained to hold land in England from the new English king; only slightly greater was the number of Flemish mercenaries, while the presence of Germans and Danes can be counted in ones and twos. More striking is the existence of the fief of the count of Boulogne in eastern England. But it is the size of the Breton contingent that is generally agreed to be the most significant. Stenton devoted several illuminating pages of his English Feudalism to the Bretons, suggesting for them an importance which he was uncertain how to define.1 To be sure, isolated studies of these minority groups have appeared, such as that of George Beech on the Poitevins, or those of J.H.Round and more recently Michael Jones on the Bretons.2 But, invaluable as such studies undoubtedly are, they tend to achieve no more for their subjects than the status of feudal curiosities, because they detach their subjects from the wider question of just what was the nature of the post-1066 ruling class of which they formed an integral part. -

Inauguration and Images of Kingship in England, France and the Empire C.1050-C.1250

Christus Regnat: Inauguration and Images of Kingship in England, France and the Empire c.1050-c.1250 Johanna Mary Olivia Dale Submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History November 2013 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis challenges the traditional paradigm, which assumes that the period c.1050-c.1250 saw a move away from the ‘biblical’ or ‘liturgical’ kingship of the early Middle Ages towards ‘administrative’ or ‘law-centred’ interpretations of rulership. By taking an interdisciplinary and transnational approach, and by bringing together types of source material that have traditionally been studied in isolation, a continued flourishing of Christ-centred kingship in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries is exposed. In demonstrating that Christological understandings of royal power were not incompatible with bureaucratic development, the shared liturgically inspired vocabulary deployed by monarchs in the three realms is made manifest. The practice of monarchical inauguration forms the focal point of the thesis, which is structured around three different types of source material: liturgical texts, narrative accounts and charters. Rather than attempting to trace the development of this ritual, an approach that has been taken many times before, this thesis is concerned with how royal inauguration was understood by contemporaries. Key insights include the importance of considering queens in the construction of images of royalty, the continued significance of unction despite papal attempts to lower the status of royal anointing, and the depth of symbolism inherent in the act of coronation, which enables a reinterpretation of this part of the inauguration rite. -

Comparative Evolutionary Thanatology of Grief, with Special Reference to Nonhuman Primates

Comparative Evolutionary Thanatology of Grief, with Special Reference to Nonhuman Primates James R. Anderson Kyoto University Abstract: The impact of the dead on the living is considered from an evolutionary comparative perspective. After a brief review of young children’s developing understanding of the concept of death, the interest of looking at how other species respond to dying and dead individuals is introduced. Solutions to managing dead individuals in social insect communities are described, highlighting evolutionarily ancient, effective behavioral mechanisms that most likely function with no emotional component. I then review examples of responses to dying and dead individuals in nonhuman primates, with particular reference to continued transport and caretaking of dead infants, responses to traumatic deaths in wild populations of monkeys and apes, and a detailed case report of the peaceful death of an old female chimpanzee surrounded by members of her group. The emotional correlates of primates’ reactions to bereavement are discussed, and some suggested evolutionarily shared responses to the dead are proposed. Key words: thanatology, death, dying, emotions, social insects, nonhuman primates, chimpanzees Thanatology can be broadly defined as the study of death and dying, and researchers from a wide range of disciplines are thanatologists. Among others, studies in medicine, biology, psychology, anthropology, palaeontology, sociology and philosophy all contribute new knowledge about the antecedents, causes, and consequences of death (e.g. Exley 2004; Haldane 2007; Klarsfeld et al. 2003; Kübler-Ross 1969; Pettitt 2011; Powner et al. 1996). Concerning people’s understanding of death, psychologists generally agree that the typical human adult’s concept of death comprises at least four sub-concepts or “components” (Speece 1995).