FELIX HEINZER Eucharist and Holy Spirit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anglican and Free Church End of Life Prayers Amen

N, go forth from this world: in the love of God the Father who created you, in the mercy of Jesus Christ who redeemed you, in the power of the Holy Spirit who strengthens you. May the heavenly host sustain you and the company of heaven enfold you. In communion with all the faithful, may you dwell this day in peace. Anglican and Free Church End of Life Prayers Amen. Loving God, in your arms we are born and in your arms we die. Prayer for the family In our sadness (and shock) contain and comfort us; Embrace each one of us with your love Most merciful God, And give us grace to let N go to new life. whose wisdom is beyond our understanding, In the name of Jesus Christ our Lord and Saviour. Amen. surround the family of N with your love, that they may not be overwhelmed by their loss, Psalm 23 but have confidence in your love, and strength to meet the days to come. The Lord is my shepherd; We ask this through Christ our Lord. therefore can I lack nothing. Amen. He makes me lie down in green pastures and leads me beside still waters. He shall refresh my soul and guide me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake. Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me. You spread a table before me in the presence of those who trouble me; you have anointed my head with oil and my cup shall be full. -

Service Music

Service Music 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 Indexes Copyright Permissions Copyright Page Under Construction 441 442 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes Plainsong Hymnody 1543 The Law of God Is Good and Wise, p. 375 800 Come, Holy Ghost, Our Souls Inspire 1560 That Easter Day with Joy Was Bright, p. 271 plainsong, p. 276 1574 In God, My Faithful God, p. 355 1200?Jesus, Thou Joy of Loving Hearts 1577 Lord, Thee I Love with All My Heart, p. 362 Sarum plainsong, p. 211 1599 How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, p. 220 1250 O Come, O Come Emmanuel 1599 Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, p. 228 13th century plainsong, p. 227 1300?Of the Father's Love Begotten Calvin's Psalter 12th to 15th century tropes, p. 246 1542 O Food of Men Wayfaring, p. 213 1551 Comfort, Comfort Ye My People, p. 226 Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Melodies 1551 O Gladsome Light, p. 379 English 1551 Father, We Thank Thee Who Hast Planted, p. 206 1415 O Love, How Deep, How Broad, How High! English carol, p. 317 Bohemian Brethren 1415 O Wondrous Type! O Vision Fair! 1566 Sing Praise to God, Who Reigns Above, p. 324 English carol, p. 320 German Unofficial English Psalters and Hymnbooks, 1560-1637 1100 We Now Implore the Holy Ghost 1567 Lord, Teach Us How to Pray Aright -Thomas Tallis German Leise, p. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

American Canticle DALE ADELMANN, DIRECTOR • DAVID FISHBURN and PATRICK A

American Canticle DALE ADELMANN, DIRECTOR • DAVID FISHBURN AND PATRICK A. SCOTT, ORGAN THE CATHEDRAL CHOIR AND SCHOLA • CATHEDRAL OF ST. PHILIP, ATLANTA, GEORGIA American Canticle DALE ADELMANN, DIRECTOR • DAVID FISHBURN AND PATRICK A. SCOTT, ORGAN THE CATHEDRAL CHOIR AND SCHOLA • CATHEDRAL OF ST. PHILIP, ATLANTA, GEORGIA 1 | Jubilate Deo 1,4,5 Craig Phillips (b.1961) 4:25 9 | Magnificat in F 1,3 Harold Friedell (b.1905-1958) 5:13 (Cathedral of St. Philip, Atlanta ) 10 | Nunc dimittis in F 1,3 4:03 2 | Magnificat 2,3 Roland Martin (b.1955) 6:05 11 | Nunc dimittis in D 2,3 Leo Sowerby (1895-1968) 4:34 3 | Nunc dimittis 2,3 4:40 (St. Paul’s Cathedral, Buffalo, in D ) 12 | Te Deum 1,4,5 Phillips 8:41 (Cathedral of St. Philip, Atlanta ) 4 | Magnificat on Plainsong Themes 2,3 Gerald Near (b.1942) 4:30 2 5 | Nunc dimittis on Plainsong Themes 2,3 3:13 13 | Beata es, Maria plainsong antiphon 0:41 2,4,6 6 | A Canticle of Praise 2,3 Larry King (1932-1990) 2:39 14 | Magnificat Martin 6:08 15 | Nunc dimittis 2,4,6 4:28 7 | Magnificat in B flat 2,3 Howard Helvey (b.1968) 6:41 (St. Paul’s Cathedral, Buffalo, in E, for trebles ) 8 | Nunc dimittis in B flat 2,3 3:46 16 | Lord, you now have set your servant free 1,3,5 Phillips 5:33 Total: 75:26 1 Cathedral Choir | 2 Cathedral Schola | 3 David Fishburn, organ | 4 Patrick Scott, organ | 5 with brass and timpani | 6 Megan Brunning, soprano 2 the music American Canticle From the time of Thomas Cranmer and his fellow English reformers, the Church’s earliest days. -

A BRIEF GUIDE to the LITURGY of the HOURS (For Private/Individual Recitation) Taken in Part From

A BRIEF GUIDE TO THE LITURGY OF THE HOURS (For Private/Individual Recitation) taken in part from http://www.cis.upenn.edu/~dchiang/catholic/hours.html Names: LOH, Divine Office, “The Office,” “The Breviary” Brief History Jewish practice: • Ps. 119:164: "Seven times a day I praise you" • perhaps originating in the Babylonian Exile (6th cent. BC): “sacrifice of praise.” • Perhaps older: synagogues • Temple use after the Exile: o Morning and Evening Prayer and at the Third, Sixth and Ninth Hours Early Christians continued • Acts 3: 1 Now Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer, the ninth hour. • Acts 10:9: The next day, as they were on their journey and coming near the city, Peter went up on the housetop to pray, about the sixth hour. Mass of the Catechumens Monastic Use Current Canonical Use: clerics, religious and laity Liturgical nature: • “why”: the prayer of the Church • “norm”: public recitation, with rubrics, etc. o chanted Instructions: • General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours • Rubrics • “Saint Joseph Guide for the Liturgy of the Hours” Sources used to pray the liturgy of the hours, either: • the 4 volume “Liturgy of the Hours” (“Breviary”) • the 1 volume “Christian Prayer”: there are various versions of this. • various “apps” for smartphones and websites as well (e.g.: http://divineoffice.org/. 1 When: The “Hours” (Note: each is also called an “office”, that is “duty”) There are seven “hours”—or each day: 1. Office of Readings [OR] or “Matins”: can be any time of day, but traditionally first 2. -

PRI Chalice Lessons-All Units

EPISCOPAL CHILDREN’S CURRICULUM PRIMARY CHALICE Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary i Locke E. Bowman, Jr., Editor-in-Chief Amelia J. Gearey Dyer, Ph.D., Associate Editor The Rev. George G. Kroupa III, Associate Editor Judith W. Seaver, Ph.D., Managing Editor (1990-1996) Dorothy S. Linthicum, Managing Editor (current) Consultants for the Chalice Year, Primary Charlie Davey, Norfolk, VA Barbara M. Flint, Ruxton, MD Martha M. Jones, Chesapeake, VA Burleigh T. Seaver, Washington, DC Christine Nielsen, Washington, DC Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary ii Primary Chalice Contents BACKGROUND FOR TEACHERS The Teaching Ministry in Episcopal Churches..................................................................... 1 Understanding Primary-Age Learners .................................................................................. 8 Planning Strategies.............................................................................................................. 15 Session Categories: Activities and Resources ................................................................... 21 UNIT I. JUDGES/KINGS Letter to Parents................................................................................................................... I-1 Session 1: Joshua................................................................................................................. I-3 Session 2: Deborah............................................................................................................. -

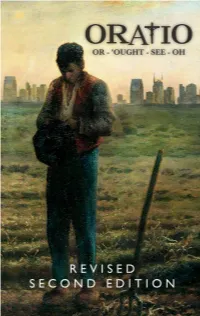

Oratio-Sample.Pdf

REVISED SECOND EDITION RHYTHMS OF PRAYER FROM THE HEART OF THE CHURCH DILLON E. BARKER JIMMY MITCHELL EDITORS ORATIO (REVISED SECOND EDITION) © 2017 Dillon E. Barker & Jimmy Mitchell. First edition © 2011. Second edition © 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-692-89224-4 Published by Mysterium LLC Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. LoveGoodCulture.com NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Jayd D. Neely Censor Librorum IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. David R. Choby Bishop of Nashville May 9, 2017 For bulk orders or group rates, email [email protected]. Special thanks to Jacob Green and David Lee for their contributions to this edition. Excerpts taken from Handbook of Prayers (6th American edition) Edited by the Rev. James Socias © 2007, the Rev. James Socias Psalms reprinted from The Psalms: A New Translation © 1963, The Grail, England, GIA Publications, Inc., exclusive North American agent, www.giamusic.com. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the Revised Standard Version Bible, Second Catholic Edition © 2000 & 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Rites of the Catholic Church © 1990, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Book of Blessings © 1988, 1990, USCCB & ICEL. All rights reserved. All ritual texts of the Catholic Church not already mentioned are © USCCB & ICEL. Cover art & design by Adam Lindenau adapted from “The Angelus” by Jean-François Millet, 1857 The Tradition of the Church proposes to the faithful certain rhythms of praying intended to nourish continual prayer. Some are daily, such as morning and evening prayer, grace before and after meals, the Liturgy of the Hours. -

Download Booklet

BYRD BRITTEN Missa Brevis Benjamin Britten | q Choral Music by William Byrd (1540-1623) Kyrie [1.52] Choristers & Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Bertie Baigent organ w Gloria [2.39] 1 O Lord, make thy servant, Elizabeth our Queen William Byrd [2.50] Choristers College Choir Bertie Baigent organ Edmund Goodman, Westcott Stark, William Barbrook treble solos 2 A Hymn of St Columba Benjamin Britten [2.07] e Chapel Choir Sanctus [1.34] Bertie Baigent organ Choristers Bertie Baigent organ 3 Nunc dimittis William Byrd [6.37] r College Choir Benedictus [1.54] Choristers 4 Jubilate Deo Benjamin Britten [2.21] Bertie Baigent organ Chapel Choir Gus Richards & Jacob Fitzgerald treble duet Jordan Wong organ t Agnus Dei [2.21] 5 Ave verum corpus William Byrd [3.53] Choristers Chapel Choir Bertie Baigent organ 6 Laudibus in sanctis William Byrd [5.02] y Quomodo cantabimus William Byrd [8.07] College Choir College Choir 7 Hymn to St Peter Benjamin Britten [5.43] u Te Deum in C Benjamin Britten [8.10] Combined Choirs Combined Choirs Jordan Wong organ Benjamin Scott-Warren, Dorothy Hoskins, Harriet Hunter solo trio Bertie Baigent organ 8 Praise our Lord, all ye gentiles William Byrd [2.32] Total timings: [67.09] Combined Choirs 9 Antiphon Benjamin Britten [5.58] Track 10 is played on the ‘Sutton’ Organ, built by Bishop & Sons in 1849. All other accompanied tracks feature the main chapel organ, built by Orgelbau Kuhn in 2007. College Choir Julia Sinclair soprano solo I Sapphire Armitage soprano solo II THE CHOIR OF JESUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE Dorothy Hoskins soprano solo III Jordan Wong organ BERTIE BAIGENT & JORDAN WONG ORGAN MARK WILLIAMS DIRECTOR 0 The Queen’s Alman William Byrd [3.26] Bertie Baigent organ www.signumrecords.com William Byrd (1540-1623) and Benjamin Britten 1976, both his pacifism and his sexual orientation words are sung simultaneously. -

12 Benediction

In the House of the Lord Lesson #12 – Homework THE SONG OF SIMEON In peace, Lord, you let your servant now depart according to your word. For my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared for ev’ry people, a light to lighten the Gentiles and the glory, the glory of your people Israel. In Luke 2, Simeon holds the eight-day old Savior of the world in his arms. He has seen the Lord’s salvation with his very own eyes. Like Simeon, at the sacrament of Holy Communion, we have been in the presence of the Son of God, our Savior. The Holy Spirit enabled Simeon to recognize that the infant carried in Mary’s arms was the Lord of heaven and heaven, hidden in humble flesh. Like Simeon, the Holy Spirit has opened our eyes of faith to recognize that the body and blood of our Lord is hidden in the humble bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper. “The Song of Simeon” is also called the “Nunc Dimittis,” which in Latin means “Now you dismiss.” At the end of the Divine Service, the Lord allows us to go in peace, having not only seeing, but also tasting our Lord. Since the fourth century, the Christian Church has sung the Nunc Dimittis as the last prayer in the Service of Evening Prayer. Since the sixteenth century, the Nunc Dimittis has also been sun immediately following Holy Communion. This is a distinctively Lutheran contribution to the Divine Service. THANK THE LORD Thank the Lord and sing his praise. -

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. 94 THE MUSICAL TIMES. NOW READY (November lst), Part I., Price 3s. 6d. SIR JOHN HAWKINS'S GENERAL HISTORY THE SCIENCE AND PRACTICE OF MUSIC. IT is intendedto issue the workin Ten Parts, price 3s. 6d. each. The whole of the original text will be printed in its integrity; together with the ILLUSTRATIVEWOODCUTS of INSTRUMENTS, &c. (for which more than 200 WOODCUTShave been engraved); the WHOLEof the MUSICAL EXAMPLES in the various ancient and modern notations; and the FAC-SIMILE EXAMPLES of OLD MANUSCRIPTS. -

Peace Evangelical Lutheran Church 325 E

Peace Evangelical Lutheran Church 325 E. Warwick Dr. ~ Alma, Michigan ~ 48801 463-5754 ~ www.peacealma.org The Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary Email: [email protected] Rev. Thomas C. Messer, Pastor and Presentation of Our Lord Jesus Home: 463-3093 ~ Cell: (989) 388-2037 LCMS T Email: [email protected] 2 February Anno Domini 2014 Welcome Welcome to the Lord’s House this morning for Divine Service. Rejoice, for the Lord comes to you here in this place to give you His gifts of forgiveness, life, and salvation through His precious means of grace – His Holy Word and Sacraments. We pray the Lord’s richest blessings upon you as you receive these Divine gifts. Please take the time to fill out the Record of Fellowship form that is in the pew. If you are visiting with us this morning, we want you to know that we are overjoyed that you are here. Please make your visit known to us by introducing yourself to us after the Service and by signing the guest book that is in the hallway on the left as you leave the sanctuary. The Lord be with us in Divine Service this morning! Holy Communion Practice The Lord’s Supper is celebrated at this congregation in the confession and glad confidence that, as He says, our Lord gives into our mouths not only bread and wine, but His very Body and Blood to eat and to drink for the forgiveness of sins and to strengthen our union with Him and with one another. In preparation for receiving this blessed Sacrament, you may refer to Martin Luther’s “Christian Questions with Their Answers” found on pages 329-330 in LSB. -

May 1 and 2, 2021

Fifth Sunday of Easter May 1 and 2, 2021 Divine Service, Setting Four with Communion Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church, Huron, South Dakota Livestream service will begin soon. Worship service bulletin at https://www.mtcalvaryhuron.org/bulletin 904 Blessed Jesus, at Your Word 904 Blessed Jesus, at Your Word 904 Blessed Jesus, at Your Word 904 Blessed Jesus, at Your Word Tune and text: Public domain Invocation P In the name of the Father and of the T Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. Exhortation P Our help is in the name of the Lord, C who made heaven and earth. P If You, O Lord, kept a record of sins, O Lord, who could stand? C But with You there is forgiveness; therefore You are feared. Exhortation P Since we are gathered to hear God’s Word, call upon Him in prayer and praise, and receive the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ in the fellowship of this altar, let us first consider our unworthiness and confess before God and one another that we have sinned in thought, word, and deed, and that we cannot free ourselves from our sinful condition. Together as His people let us take refuge in the infinite mercy of God, our heavenly Father, seeking His grace for the sake of Christ, and saying: God, be merciful to me, a sinner. Confession of Sins C Almighty God, have mercy upon us, forgive us our sins, and lead us to everlasting life. Amen. Absolution P Almighty God in His mercy has given His Son to die for you and for His sake forgives you all your sins.