Wisconsin Progressives Had Regressiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Refining the UW–Madison Campus Dan Okoli, NCARB, AIA University Architect

Beneficent Beauty: Refining the UW–Madison Campus Dan Okoli, NCARB, AIA University Architect WISCAPE – Presentation 10.27.08 Campus Design Guide University of Wisconsin-Madison An Approach to a Functional and Pleasing Composition QUESTION 3 What should our campus look and feel like in the near and long term? GOOD EXAMPLES OF WHAT NOT TO DO 4 McFadden Hall, 1919 GOOD EXAMPLES OF WHAT NOT TO DO 5 McFadden Hall, 1919 After 1960’s Renovation Schear Hall,1960’s Addition GOOD EXAMPLES OF WHAT NOT TO DO 6 McFadden Hall, 1919 After 1960’s Renovation 2008 Renovation GREAT CAMPUS PLACES 7 Memorial Union Terrace Memorial Union Terrace Memorial Union Memorial Union Interior Bascom Hill Memorial Union Interior Bascom Hall Bascom Hill Bascom Hall GREAT CAMPUS PLACES 8 Bascom Hill Bascom Hall Memorial Union Terrace Agricultural Hall Library Mall Allen Centennial Gardens Lakeshore Path BascomScience Hill Hall and Bascom Hill School of Education NOT SO GREAT CAMPUS PLACES 9 NOT SO GREAT CAMPUS PLACES 1 0 Old Ogg Hall Van Vleck Plaza Engineering Research Building Van Hise Hall Humanities Building Peterson Building Social Sciences Building Union South Biotron Laboratory EDUCATION BUILDING EXAMPLE 1 1 Selected Design Option Open Space North of Education Building North Elevation of Education Building Interior Atrium BIOCHEMISTRY I EXAMPLE 1 2 BIOCHEMISTRY II EXAMPLE 1 3 BIOCHEMISTRY I 1 4 BIOCHEMISTRY COMPLEX 1 5 WISCONSIN INSTITUTES FOR DISCOVERY 1 6 WISCONSIN INSTITUTES FOR DISCOVERY 1 7 WISCONSIN INSTITUTES FOR DISCOVERY 1 8 WISCONSIN INSTITUTES FOR DISCOVERY -

The Wisconsin Idea: the Vision That Made Wisconsin Famous

1 “Trying to plan for the future without a sense of the past is like trying to plant cut flowers” --Daniel Boorstin, historian and Librarian of Congress The Wisconsin Idea: The Vision that Made Wisconsin Famous Introduction To the practitioners who comprise UW-Madison’s Community Partnerships and Outreach (CPO) Staff Network, the Wisconsin Idea is at the heart of their day-to-day work with communities in Wisconsin and beyond. But the original meaning of the Wisconsin Idea has faded over time, replaced by a generic public service mandate. (1) “The Boundaries of the University are the Boundaries of the State” The “Year of the Wisconsin Idea” offers us an opportunity to reflect on how the Wisconsin Idea guides our practice. We chose to explore the history of the emergence of the Wisconsin Idea in an attempt to renew and clarify our vision for why and how we engage with the public to address pressing issues. It turns out that the history of the University’s engagement with the State offers much more relevant guidance than we would have imagined. The values that drove the founders of the WI Idea—truth, self- governance, egalitarianism, integrity, trust and social capital—are the same values that represent effective, democratic partnerships today. It’s evident in our practice, and now it’s evident in our history as well, thanks to the work of Gwen Drury, Ph.D. student in Educational Policy and Leadership Analysis at UW-Madison. The rich history she details here brings us closer to our best practices—equitable, reciprocal engagement in which knowledge is co-created by the University and communities working together on issues that matter to all of us. -

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN

Spring 2008 Volume 109, Number 1 WISCONSIN Reluctant Star 18 The UW scientist who first brought stem cells into the scientific spotlight — a discovery that sparked a volatile debate of political and medical ethics — doesn’t seek fame for himself. So when you are the go-to guy for everybody who wants access to James Thomson, a man who’d much rather be in the lab than in the media’s glare, you learn to say no more often than you’d like. By Terry Devitt ’78, MA’85 Seriously Funny 22 Some thought that Ben Karlin ’93 was walking away from success when he left his job as executive producer for TV’s The Daily 18 Show and The Colbert Report. But, as he explains in this conversation with On Wisconsin, he was simply charting a comedic path that includes a new book and his own production company. By Jenny Price ’96 Can of Worms 28 Graduate students have more to worry about than grades — there’s also research, funding, and, as the students working in one lab discovered, their mentor’s ethics. While PhD candidate Amy Hubert x’08 aims to overcome scandal and put the finishing touches on her degree, the UW struggles to protect the students who will create the future of science. 22 By John Allen INSIDE Campus on $5 a Day LETTERS 4 34 If a bill featuring Abe’s face is burning a hole in your pocket, SIFTING & WINNOWING 9 you’d be amazed to learn what it can buy on campus. Don some comfort- DISPATCHES 10 able shoes and discover what you can eat, see, and do at bargain prices. -

DANE COUNTY CULTURAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION 2012 Grant Advisory Panels Bios

DANE COUNTY CULTURAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION 2012 Grant Advisory Panels Bios Arts in Education Brenda Baker is Director of Exhibits at Madison Children’s Museum, a visual artist and mother of two young boys. She has a B.A. in art from DePauw University and an M.F.A. in painting and sculpture from UW‐Madison and has received numerous awards for her work including NEA, Fulbright and DCCAC grants. John Beutel earned a BS and MS Degree in Choral Music Education from the University of Wisconsin‐ Platteville. He retired in 2001 after 35 years of teaching public school choral music. The last 26 years he was Choir Director at Stoughton High School. He continues his involvement in music by conducting the Stoughton Chamber Singers, the Stoughton Festival Choir and two church choirs at Christ Lutheran church. He is a member of the Stoughton Opera House Board of Directors, was a founding member of the Stoughton Arts Council, and currently teaches an adult course in Music Appreciation for any community members who love music and would like to learn more about it. John also has been an active member of the Wisconsin School Music Association (WSMA) having served on its Adult Education Committee, various Festival Music Selection Committees, and chairing the State Middle Level Honors Choir. He currently serves as an adjudicator for WSMA school music festivals and honors auditions at the district and state levels in Wisconsin and Michigan. Extensive travel and gardening are passions that offer non musical enrichment. Kimberly Foster Branch is a Certified MBTI Practitioner (Myers‐Briggs), who has taught pre‐school and elementary school in Australia, Los Angeles and New York City for over 15 years. -

October 10, 2019 Chancellor Rebecca

October 10, 2019 Chancellor Rebecca Blank Office of the Chancellor 161 Bascom Hall 500 Lincoln Drive Madison, WI 53706 RE: Student Free Speech and Safety Concerns Dear Chancellor Blank, I am writing to you today regarding a very troubling event that took place this past Wednesday on your campus and which has been widely reported in local and online media. As reported by the Wisconsin State Journal, a UW-Madison student was video-taped defacing the windows of the UW-Madison College Republicans’ office on campus with demeaning signs containing highly-charged, visceral language which were seemingly meant to intimidate and cause a disturbance. Additionally, the student engaging in this behavior was doing so while blaring a song on her phone entitled “FDT” (F*** Donald Trump) by rapper YG which, in addition to explicit language, contain inferences towards the harming of the President of the United States. Further, according to the Wisconsin State Journal article reporting the matter, when a university employee approached the student requesting that she please stop, the student replied with an expletive and aggressive language and refused to stop. The article continues, “Two female students were in the office during the duration of the [events] and Christens said they feared for their safety, afraid to leave because of the demonstrator’s aggressive behavior.” As a result of these events, I am requesting a thorough investigation into this matter by you, the UW’s Office of Student Conduct and Community Standards, and the UW Police Department. Additionally, I request that you provide me – consistent with all laws and regulations - with a complete report as to the process UW will be using to investigate and respond, findings from the investigation, including any disciplinary actions resulting therefrom, as well as any modifications and/or clarifications to UW’s campus free speech policy and any anti-intimidation and anti- harassment policy. -

Wisconsin Alumni Association || Onwisconsin Spring 2012

For University of Wisconsin-Madison Alumni and Friends Micro to Macro A tiny fly leads a UW geneticist to fruitful discoveries. SPRING 2012 WISCONSIN ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Familiar Territory For David Ward, it’s the same, yet so different. 150 YEARS Fat Fighter Is a healthy diet a human right? Space Dreams Badger alumnae reach sky-high goals. Rune-Nation Seeking the truth behind mysterious markings. The power of many gives power to many. Join the great people who make Great People possible. uwgreatpeople.org GP ad Fall 11ad-4_lg.indd 1 8/8/11 4:59 PM SPRING 2012 contents VOLUME 113, NUMBER 1 Features 22 Ward 2.0 By Jenny Price ’96 As he leads the university for a second time and agrees to a second year as interim chancellor, David Ward talks about embracing innovation during difficult times. 24 Lord of the Flies By Jill Sakai PhD’06 It took multiple bus rides for a young Barry Ganetzky to attend college classes each day. That same single- mindedness has nourished the UW researcher’s longtime career, pushing him to study tiny creatures and find ways to treat human disease. 30 Shared Space By Jenny Price ’96 30 Three dreams — and three dreams come true: these Badger alumnae are using their engineering degrees by working for NASA, contributing to America’s exploration 38 of space, and mentoring those who will follow. 38 Leading the War on Obesity By Melba Newsome Barry Popkin ’67, MS’69 long ago predicted the current obesity epidemic — and the former civil rights activist is now fighting for the right to a healthy diet for all. -

The Washburn Observer

The Washburn Observer Volume 1, No. 2 • Fall 2011 • www.astro.wisc.edu SALT Commissioning Produces Unique Proposals, Experiences Inside This Issue The Proposals in star formation and black hole activity triggered by a merger between two Letter from the Chair 2 W astronomy people are really excited about galaxies. “SALT’s Fabry-Perot capability Please Keep in Touch 2 Uusing the South African Large Telescope enables us to observe a spectral line at Kelley Hess Balances (SALT)—so much so that they’ve asked for more each position of the extended ionized Science and Sports 3 observation time in the coming semester than the gas cloud across a wide field of view,” 135 hours that are available for UW-Madison. says Corey. Universe in the Park 4 Fifteen proposals were accepted to use the UW John Chisholm, a second-year Department Welcomes time. Astronomy graduate students are especially graduate student, proposes to use RSS First Grainger Fellow 5 excited about the telescope’s new capabilities. to observe an extremely unusual galaxy News Notes 5 Third-year graduate student Greg Mosby culled from a survey of several hundred is enthusiastic about using the new Robert thousand distant galaxies. The galaxy Stephan Jansen Retires 6 Stobie Spectrograph (RSS) to better understand is remarkable because of the strong and Jack Honor Finds Perfect Fit 7 how massive galaxies are influenced by the broad lines of highly ionized oxygen supermassive black holes lurking at their centers. and neon in its spectrum, indicating Board of Visitors 7 This fall, he is undertaking a pilot study focused very energetic processes in the galaxy. -

WISCONSIN MAGAZINE of HISTORY the State Historical Society Ofwisconsin • Vol

(ISSN 0043-6534) WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY The State Historical Society ofWisconsin • Vol. 75, No. 3 • Spring, 1992 fr»:g- •>. * i I'^^^^BRR' ^ 1 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Director Officers FANNIE E. HICKLIN, President GERALD D. VISTE, Treasurer GLENN R. COATES, First Vice-President H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Secretary JANE BERNHARDT, Second Vice-President THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN is both a state agency and a private membership organization. Founded in 1846—two years before statehood—and chartered in 1853, it is the oldest American historical society to receive continuous public funding. By statute, it is charged with collecting, advancing, and dissemi nating knowledge ofWisconsin and ofthe trans-Allegheny West The Society serves as the archive ofthe State ofWisconsin; it collects all manner of books, periodicals, maps, manuscripts, relics, newspapers, and aural and graphic materials as they relate to North America; it maintains a museum, library, and research facility in Madison as well as a statewide system of historic sites, school services, area research centers, and affiliated local societies; it administers a broad program of historic preservation; and publishes a wide variety of historical materials, both scholarly and popular. MEMBERSHIP in the Society is open to the public. Individual memhersh'ip (one per son) is $25. Senior Citizen Individual membership is $20. Family membership is $30. Senicrr Citizen Family membership is $25. Suppcrrting memhershvp is $100. Sustaining membership is $250. A Patron contributes $500 or more. Life membership (one person) is $1,000. MEMBERSHIP in the Friends of the SHSW is open to the public. -

THE KEY VOL 79 NO 3 AUTUMN 1962.Pdf

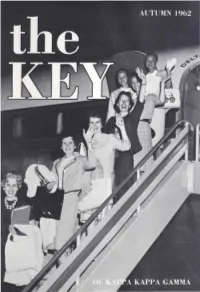

VOLUME 79 NUMBER 3 The first college women's frat ernity magazine Published continuously the KEY since 1882 OF KAPPA KAPPA GAMMA AUTUMN 1962 Send all editorial material and COVER: Airborne Kappas arrive on the first charter flight to correspondence to the a Kappa convention. Ranging up the steps, they are: Barbara EDITOR Russell Kunz, n A-Illinois, Champaign-Urbana alumna dele Mrs. Robert H . Simmons gate; Sue Sather, n IT-Washington, active delegate; ~ancy 15 6 North Roosevelt Avenue Columbus 9, Ohio Sampson Nethercutt, r H-Washington State, alumna VISitor; Virginia Pitts Malico, r r-Whitman, Spokane alumna deleg_ate; Martha Lynn, X-Minnesota, active visitor; Karen Rushmg, Send all business i terns to the X-Minnesota, active delegate; Diane Haas Clover, n-Kansas, BUSINESS MANAGER adviser to r Z-Arizona. Miss Clara 0. Pierce Fraternity Headquarters 530 East Town Street 3 Devotional given at opening session Columbus 16, Ohio (For other devotionals, see pages 11, 27, 29, 43, and 45) Send changes of address, six weeks prior to month of pub .. 4 " ... four square to all the winds that blow" lication, to 9 What I wish for a fraternity chapter FRATERNITY HEADQUARTERS 12 The rest is our own doing 530 East Town Street 19 The state of the Kappa union Columbus 16, Ohio 22 "All mimsy were the Borogoves" (Duplicate copies cannot be sent to replace those unde 23 Scholarship grants announced livered through failure to send advance notice.) 28 The World and K K r 30 A bit of this and that Deadline dates are August 1, September 25, November 15, 32 Alumnre Day activity January 15 for Autumn, Winter, Mid-Winter, and 33 Magazine sales bring rewards Spring issues respectively. -

RELEASE: UW System Presidential Search Committee Named

University Relations 1700 Van Hise Hall, 1220 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706 wisconsin.edu • facebook.com/uwsystem • twitter.com/uwsystem [email protected] or 608-263-1700 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 9, 2021 News Release UW System Presidential Search Committee named MADISON, Wis.—Edmund Manydeeds III, President of the University of Wisconsin System Board of Regents, today appointed a 19-member Search and Screen Committee to help identify the next UW System President. Current President Tommy Thompson has been serving in an interim role since July 1, 2020. He replaced Ray Cross, who retired after a 42-year career in higher education, including serving as UW System President from February 2014 to June 2020. Regent Vice President Karen Walsh will chair the Search and Screen Committee. Other members of the committee are: • Warren Anderson, Senior Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Officer, UW System • Robert Atwell, Regent • Rebecca Blank, Chancellor, UW-Madison • Amy Blumenfeld Bogost, Regent • Johannes Britz, Provost, UW-Milwaukee • Michael Falbo, Regent President Emeritus • Deborah Ford, Chancellor, UW-Parkside • Rob Manzke, Chief of Staff, Chancellor’s Office, UW-Stevens Point • Sabrina Mueller-Spitz, Associate Professor of Biology, UW Oshkosh • Geoffrey Peterson, Professor of Political Science and American Indian Studies, UW-Eau Claire • Dr. Ashok Rai, Regent • Glendali Rodriguez, Interim Provost, UW-Stout • Corey Saffold, Regent and Student, UW-Whitewater • Paul Shain, Vice Chair, Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association, and President/CEO, Singlewire Software, LLC • Jon Shelton, Associate Professor, and Chair, Democracy and Justice Studies, UW-Green Bay • Dennis Shields, Chancellor, UW-Platteville • Artanya Wesley, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, UW-Whitewater • Olivia Woodmansee, Regent Emeritus and Student, UW-La Crosse “President Thompson has reminded us of the power of the Wisconsin Idea,” said Manydeeds. -

Keep On, Wisconsin. Keep On

Keep On, Wisconsin. Keep On. An update from the Office of University Relations on strategic priorities to advance the UW–Madison brand 2013 – 2014 Table of Contents 2 Introduction: Communication that Connects 3 A Message from the Vice Chancellor for University Relations 4 A Brief History 5 Who We Are 6 Our Strategic Framework 7 University Communications: Telling Our Story of Success 9 University Marketing: Building the Brand 11 Strategic Partnerships: Building Bridges 13 Statewide Outreach and Engagement Initiative: Showing Value and Connection 14 Keep on Achieving: Our Accomplishments 14 Cool Projects 17 The Big Stories 19 Connecting with Campus 21 Reaching Beyond Campus 25 Welcoming Others to Campus 27 Public Resources 28 National Recognition 29 A Final Word: Keeping On Communication that Connects The niversityU of Wisconsin–Madison is building a better future for Wisconsin and for the world. That’s a bold statement, but one that is supported by a multitude of success stories generated throughout the university’s 166 years of existence. These stories of our accomplishments in pioneering research, excellence in the classroom and a tradition of outreach through the Wisconsin Idea provide a compelling narrative that strengthens the UW–Madison brand and provides a lens through which the public views our work. And the vibrant partnerships that UW–Madison forges in Wisconsin and around the world are igniting entrepreneurship, creating jobs, and helping to build and strengthen our communities. We’re building even stronger ties to business and industry and making sure that we are a good neighbor in communities throughout the state. We’re also helping policymakers in Madison and Washington, D.C., better under- stand the higher-education landscape, the challenges faced by UW–Madison, and the educational needs of students and their families.