ENGLISH-LANGUAGE THEATRES in POST-COMMUNIST PRAGUE By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Alternative Facts" and Hate: Regulating Conspiracy Theories That Take The

Hay Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 6/30/20 7:10 PM “ALTERNATIVE FACTS” AND HATE: REGULATING CONSPIRACY THEORIES THAT TAKE THE FORM OF HATEFUL FALSITY SAMANTHA HAY I. INTRODUCTION Prepare for the invasion! Hurry, a caravan of migrants, MS-13 gang members, and terrorists forcefully march on our southern border. Don’t be fooled by their asylee disguise and the children that accompany them; these people are dangerous and well funded by Jewish globalist George Soros. They are coming to invade our country. This is the all too familiar caravan narrative. It is a falsity, built upon the large group of migrants journeying to the United States in the hopes of declaring asylum. Both the invasion itself and the Jewish globalists’ role as puppeteers are falsehoods. The “narrative” is also an expression of hate— hate of immigrants, Central and Latin Americans, and Jews. The false narrative spread from conspiracy theorists’ inner circles, making its way to widely followed media outlets, cable news, and then President Trump’s Twitter feed.1 USA Today traced the conspiracy theory’s focus on George Soros’ involvement to an internet post from October 14, 2018, by a conspiracy theorist with six thousand followers who frequently posts about “white genocide.”2 Within hours, it appeared on six Facebook pages whose membership totaled over 165,000 users; just four days later this portion of the conspiracy theory reached over two million people.3 It continued to spread like wildfire from there, making its way to mainstream platforms. This speech is false speech. This speech is hateful speech. -

The Digital Experience of Jewish Lawmakers

Online Hate Index Report: The Digital Experience of Jewish Lawmakers Sections 1 Executive Summary 4 Methodology 2 Introduction 5 Recommendations 3 Findings 6 Endnotes 7 Donor Acknowledgment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In late 2018, Pew Research Center reported that social media sites had surpassed print newspapers as a news source for Americans, when one in five U.S. adults reported that they often got news via social media.i By the following year, that 1 / 49 figure had increased to 28% and the trend is only risingii. Combine that with a deeply divided polity headed into a bitterly divisive 2020 U.S. presidential election season and it becomes crucial to understand the information that Americans are exposed to online about political candidates and the topics they are discussing. It is equally important to explore how online discourse might be used to intentionally distort information and create and exploit misgivings about particular identity groups based on religion, race or other characteristics. In this report, we are bringing together the topic of online attempts to sow divisiveness and misinformation around elections on the one hand, and antisemitism on the other, in order to take a look at the type of antisemitic tropes and misinformation used to attack incumbent Jewish members of the U.S Congress who are running for re-election. This analysis was aided by the Online Hate Index (OHI), a tool currently in development within the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Center for Technology and Society (CTS) that is being designed to automate the process of detecting hate speech on online platforms. Applied to Twitter in this case study, OHI provided a score for each tweet which denote the confidence (in percentage terms) in classifying the subject tweet as antisemitic. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Twenty Years After the Iron Curtain: the Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010

Twenty Years after the Iron Curtain: The Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010 Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic n November of last year, the Czech Republic commemorated the fall of the communist regime in I Czechoslovakia, which occurred twenty years prior.1 The twentieth anniversary invites thoughts, many times troubling, on how far the Czechs have advanced on their path from a totalitarian regime to a pluralistic democracy. This lecture summarizes and evaluates the process of democratization of the Czech Republic’s political institutions, its transition from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy, and the transformation of its civil society. Although the political and economic transitions have been largely accomplished, democratization of Czech civil society is a road yet to be successfully traveled. This lecture primarily focuses on why this transformation from a closed to a truly open and autonomous civil society unburdened with the communist past has failed, been incomplete, or faced numerous roadblocks. HISTORY The Czech Republic was formerly the Czechoslovak Republic. It was established in 1918 thanks to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his strong advocacy for the self-determination of new nations coming out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the World War I. Although Czechoslovakia was based on the concept of Czech nationhood, the new nation-state of fifteen-million people was actually multi- ethnic, consisting of people from the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), Slovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia (today’s Ukraine), and approximately three million ethnic Germans. Since especially the Sudeten Germans did not join Czechoslovakia by means of self-determination, the nation- state endorsed the policy of cultural pluralism, granting recognition to the various ethnicities present on its soil. -

A Supplementary Figures and Tables

A Supplementary figures and tables This Online Appendix provides supplementary material and is for online publication only. A1 Figure A1: Population in the Czech lands (in millions) 10 8 6 4 2 Total population Czechs Germans 0 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020 Notes: The figure shows total population of the Czech Republic (Czech lands consisting of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia) between 1921 and 2011 (light gray), and population by self-declared ethnicity (black and dark gray). The German population (dark gray bullets) was almost entirely expelled in 1945 and 1946 and partly replaced by residents mainly from Czech hinterlands and Slovakia. ‘Czechs’ refers to all other non-German residents (black triangles). A2 Figure A2: Demarcation line and pre-existing infrastructure 1930 counties 1938 Sudetenland Main roads and railways Rivers Notes: The maps compare the demarcation line between US and Red Army forces in 1945 Czechoslovakia (red line) to county boundaries as of 1930, Sudetenland as of the Munich Agreement in 1938, main roads and railways, and rivers. A3 Figure A3: Demarcation line between US and Red Army forces in 1945 Czechoslovakia US-liberated Sudetenland Red Army-liberated Sudetenland Notes: The map zooms into Figure 1 in the main text. The red line represents the demarcation line between US and Red Army forces in 1945 Czechoslovakia, which runs from Karlovy Vary over Plzeň to České Budějovice (black dots). Prague is the capital city. The US-liberated regions of Sudetenland are in dark gray, the Red Army-liberated regions are in light gray. Sudetenland was settled by ethnic Germans and annexed by Nazi Germany in October 1938. -

Games+Production.Pdf

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Banks, John& Cunningham, Stuart (2016) Games production in Australia: Adapting to precariousness. In Curtin, M & Sanson, K (Eds.) Precarious creativity: Global media, local labor. University of California Press, United States of America, pp. 186-199. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/87501/ c c 2016 by The Regents of the University of California This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. License: Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.ucpress.edu/ book.php?isbn=9780520290853 CURTIN & SANSON | PRECARIOUS CREATIVITY Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Precarious Creativity Precarious Creativity Global Media, Local Labor Edited by Michael Curtin and Kevin Sanson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Communism with Its Clothes Off: Eastern European Film Comedy and the Grotesque A Dissertation Presented by Lilla T!ke to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Lilla T!ke 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Lilla T!ke We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. E. Ann Kaplan, Distinguished Professor, English and Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies, Dissertation Director Krin Gabbard, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies, Chairperson of Defense Robert Harvey, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies and European Languages Sandy Petrey, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies and European Languages Katie Trumpener, Professor, Comparative Literature and English, Yale University Outside Reader This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Communism with Its Clothes Off: Eastern European Film Comedy and the Grotesque by Lilla T!ke Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University 2010 The dissertation examines the legacies of grotesque comedy in the cinemas of Eastern Europe. The absolute non-seriousness that characterized grotesque realism became a successful and relatively safe way to talk about the absurdities and the failures of the communist system. This modality, however, was not exclusive to the communist era but stretched back to the Austro-Hungarian era and forward into the Postcommunist times. -

March 11 - 21, 2021 Author Biographies

Calvary Theatre Arts Presents TheFantasticks Book and Lyrics by Music by TOM JONES HARVEY SCHMIDT March 11 - 21, 2021 Author Biographies Composer Harvey Schmidt and lyricist Tom Jones are the legendary writing team best known for shaping the American musical landscape with their 1960 hit, The Fantasticks. After its Off-Broadway opening in May 1960, it went on to become the longest-running production in the history of the American stage and one of the most frequently produced musicals in the world. Their first Broadway show, 110 in the Shade, was revived on Broadway in a new production starring Audra MacDonald. I Do! I Do!, their two-character musical starring Mary Martin and Robert Preston, was a success on Broadway and is frequently done around the country. For several years Jones and Schmidt worked privately at their theatre workshop, concentrating on small-scale musicals in new and often untried forms. The most notable of these efforts were Celebration, which moved to Broadway, and Philemon, which won an Outer Critics Circle Award. They contributed incidental music and lyrics to the Off-Broadway play Colette starring Zoe Caldwell, then later did a full-scale musical version under the title Colette Collage. The Show Goes On, a musical revue featuring their theatre songs and starring Jones and Schmidt, was presented at the York Theatre, and Mirette, their musical based on the award-winning children's book, was premiered at the Goodspeed Opera House in Connecticut. In addition to an Obie Award and the 1992 Special Tony Award for The Fantasticks, Jones and Schmidt were inducted into the Broadway Hall of Fame at the Gershwin Theatre, and on May 3, 1999 their 'stars' were added to the Off-Broadway Walk of Fame outside the Lucille Lortel Theatre. -

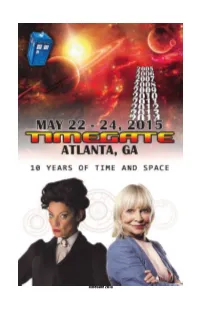

Timegate 2015

TimeGate 2015 WELCOME TO TIMEGATE 2015 We’re thrilled you’ve joined us for our 10th YEAR OF TIMEGATE in our new hotel, the Marriott Century Center!! The past decade has brought lots of exciting developments in the worlds of Doctor Who and sci-fi/fantasy in general. We’ve got lots to celebrate… not least the fact that it’s also 10 years since Who returned to TV screens in a big way and became more popular than ever! To commemorate this, we’ve put together a thrilling assortment of guests and events bridging classic and new Doctor Who… not to mention the latest in other fantastical movies, TV, com- ics, and books. We have two new stations for your assistance — Information Services and the TimeGate Store. If you are new to TimeGate, join our First-Timers panel and tour on Friday at 7:00 p.m. Buy your Charity Cabaret tickets, TimeGate shirts, and VIP guest autograph/photograph tickets at the new TimeGate store! Also, be sure to explore the wonders of our bigger dealers room! PLEASE support our Charity Cabaret on Saturday night. There is a $5.00 additional admission. It is well worth the small additional expense for the extra performances by our guests, who are doing this for the charity. 100% of the proceeds will go to support the Nepal Youth Foundation. Please buy your ticket at the TimeGate store before the event. Let us transport you into the worlds of Doctor Who (among many others), as we ’phase’ you away to a weekend of fun-filled imagination! Many thanks to our Immortals, our sponsors, the great staff of the Marriott Century Center, and to our fantastic Senior Directors, Directors and staff, who make TimeGate such a huge success! Special thanks to Robert Lloyd for creating this program book, and to Tony Cade and Challenges Games and Comics for giving us space for making badges! Alan Siler Susan Rey IN MEMORY GEORGE COCKRELL TimeGate has been going for ten years now, and George was there for nearly all of it, even though he lived in Illinois. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Rondo Oral History Project Minnesota Historical Society

Transcript of an oral history interview with Bernice Wilson with comments by daughter PATRICIA WILSON CRUTCHFIELD Thursday, March 20, 2003 at Crutchfield Residence Saint Paul, Minnesota Interviewed By Kateleen Hope Cavett Project as part of Society HAND in HAND's RONDO ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Saint Paul,History Minnesota Bernice Wilson did this interview at the age of eighty-two years. Mrs. Wilson discusses her disgust over the lack of respectable employment opportunities and frustration over theHistorical conservative laws that existed in Minnesota when she movedOral to Saint Paul from Chicago in 1949. Mrs. Wilson advised that she was a mother first, but at our request she details the social clubs the existed in the Black community. These clubs were created because Blacks were not welcome at many White owned establishments. She states, ''It was a fantastic social life, a fantastic social life." She describes the community support when her husbandRondo and son died, and her love for traveling. Pat Wilson Crutchfield, at age fifty-seven years, shares her mother's memory of the community support when her father passed away, and also discusses her involvementMinnesota in the church, and her experiences being raised as a "village child," as in the old African proverb, ''It takes a village to raise a child." This is a verbatim transcript of a taped interview, edited for clarity. Signed releases are on file from Mrs. Wilson and Mrs. Crutchfield. 3 BW: Bernice Wilson KC: Kate Cavett BW: I'm Bernice Wilson,1 mother of Patricia Wilson. Do you want to know where I live? KC: I'd love to know where you live.