Your Yard, Your Shrubs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Name Common Name Plant Type Plant Form References at Bottom

Diablo Firesafe Council The following list of plants contains those found in the references that were recommended for use in fire prone environments by at least 3 references. All of the plants listed here were given either a high or moderate fire resistance rating in the references where a rating was assigned, or found listed in the references that categorized plants as fire resistant without assigning a degree of resistance. In most cases, the terms used in the ranking were not defined, and if they were, there is no agreed upon standard definition. For this reason, the plants are listed in this chapter without any attempt to rank them. The list is sorted by plant form -- groundcovers, shrubs, trees, etc. Some species may appear twice (e.g. once as a groundcover and then again as a shrub) because they have properties attributed to both forms. For a complete description of the plant, including its mature characteristics, climate zones, and information on erosion control and drought tolerance, please refer to Chapter 4, the landscape vegetation database. It is important to note that a plant's fire performance can be seriously compromised if not maintained. Plants that are not properly irrigated or pruned, or that are planted in climate areas not generally recommended for the plant, will have increased fire risk and will likely make the mature plant undesirable for landscaping in high fire hazard zones. Table 1. Plants with a favorable fire performance rating in 3 or more references. Some plants may have invasive (indicated as ), or other negative characteristics that should be considered before being selected for use in parts of California. -

Shrub Swamp State Rank: S5 - Secure

Shrub Swamp State Rank: S5 - Secure cover of tall shrubs with Shrub Swamp Communities are a well decomposed organic common and variable type of wetlands soils. If highbush occurring on seasonally or temporarily blueberries are dominant flooded soils; They are often found in the transition zone between emergent the community is likely to marshes and swamp forests; be a Highbush Blueberry Thicket, often occurring on stunted trees. The herbaceous layer of peat. Acidic Shrub Fens are shrub swamps is often sparse and species- peatlands, dominated by poor. A mixture of species might typically low growing shrubs, along include cinnamon, sensitive, royal, or with sphagnum moss and marsh fern, common arrowhead, skunk herbaceous species of Shrub Swamp along shoreline. Photo: Patricia cabbage, sedges, bluejoint grass, bur-reed, varying abundance. Deep Serrentino, Consulting Wildlife Ecologist. swamp candles, clearweed, and Emergent Marshes and Description: Wetland shrubs dominate turtlehead. Invasive species include reed Shallow Emergent Marshes Cottontail, have easy access to the shrubs Shrub Swamps. Shrub height may be from canary grass, glossy alder-buckthorn, are graminoid dominated wetlands with and protection in the dense thickets. The <1m to 5 meters, of uniform height or common buckthorn, and purple <25% cover of tall shrubs. Acidic larvae of many rare and common moth mixed. Shrub density can be variable, loosestrife. Pondshore/Lakeshore Communities are species feed on a variety of shrubs and from dense (>75% cover) to fairly open broadly defined, variable shorelines associated herbaceous plants in shrub (25-75% cover) with graminoid, around open water. Shorelines often swamps throughout Massachusetts. herbaceous, or open water areas between merge into swamps or marshes. -

Nannyberry (Viburnum Lentago)

BWSR Featured Plant Name: Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) Plant Family: Caprifoliaceae Statewide Wetland Indicator Status: Great Plains – FACU Nannyberry is a shrub that is both beautiful and Midwest – FAC versatile. This shade-tolerant, woody plant has flat N. Cent. N. East – FAC topped white flowers, fruit that is used by a wide variety of birds and wildlife, and vibrant fall color. Frequently used as a landscaping plant, it is successful as a tall barrier and wind break. Its ability to function as both a small tree and multi-stemmed shrub and ability to adapt to many environmental conditions makes it well suited to buffer planting and other soil stabilization projects. Flat-topped flower clusters and finely serrated leaves Identification This native shrub can be identified by its pointed buds, unique flowers, and fruit. Growing to around twelve feet tall in open habitats, the species commonly produces suckers and multiple stems. The newest branches are light green in color and glabrous and buds narrow to a point. With age, the branches become grey, scaly and rough. The egg-shaped leaves are simple and opposite with tips abruptly tapering to a sharp point. Leaf surfaces are shiny, dark green and hairless with reddish finely serrated margins. Fall color is a vibrant dark red. Numerous dense, flat-topped flower heads appear and bloom from May to June. Flowers are creamy white and bell to saucer-shaped. The flowers develop into elliptical berry-like drupes that turn a blue-black color from July to August. The Multi-stemmed growth form sweet and edible fruit is used by a variety of wildlife species but has a wet wool odor when decomposing, thus its alternate name – Sheepberry. -

Pruning Shrubs in the Low and Mid-Elevation Deserts in Arizona Ursula K

az1499 Revised 01/16 Pruning Shrubs in the Low and Mid-Elevation Deserts in Arizona Ursula K. Schuch Pruning is the intentional removal of parts of a plant. visibility and safety concerns is sometimes necessary. These Pruning needs of shrubs commonly planted in the low and can be minimized by allowing sufficient space for the plant mid-elevation deserts in Arizona vary from no pruning to reach its mature size in the landscape. Renovating or to regular seasonal pruning. Requirements vary by plant rejuvenating old or overgrown shrubs through pruning species, design intent, and placement in a landscape. Fast generally improves the structure and quality of the plant, growing shrubs generally need frequent pruning from the and results in improved displays for flowering shrubs. Some time of establishment until maturity, while slow growing shrubs are grown as formal hedges and require continuous shrubs require little to none. Pruning should only be done pruning to maintain their size and shape. when necessary and at the right time of year. Using the natural growth form of a shrub is a good guide for pruning. Shearing shrubs should be avoided except for maintenance of formal How to prune? hedges or plant sculptures. All pruning should be done with Selective thinning refers to removing branches back to the sharp hand pruners or, for thicker stems, loppers. point of attachment to another branch, or to the ground. This type of pruning opens the plant canopy, increasing light and air movement (Figure 1). Thinning cuts do not stimulate Why prune? excessive new growth. They serve to maintain the natural Reasons for pruning shrubs include maintenance of plant growth habit of the shrub. -

What Is a Shrub?

What is a shrub? The man behind the beverage counter at the festival asked me if I ever had a great shrub. With questioning eyes, I imagined that beautiful green evergreen that grows outside our house. I guess he knew that I had no idea why he was asking me that question since he started to laugh as he explained that it is fruit syrup preserved with vinegar and mixed with water or alcohol to create a very refreshing drink. It seems that this is an old fashioned idea that was used to preserve seasonal fruit, creating fresh flavored syrup that can be used for beverages, salad dressings, or meat glazes. Adding vinegar to water helped make it safe to drink for Babylonians and even Romans made a beverage like this called posca. Early colonial sailors carried those vitamin C enhanced shrubs to prevent scurvy. Many older cookbooks or well as some recent ones have recipes for shrubs. As I researched shrub recipes, I found several different methods. Most of them involved creating fruit-flavored vinegar and adding sugar to it. The vinegar acts as the preserving agent, allowing fresh fruits to turn into flavorful syrups. The ingredients are simple: Fresh fruit, vinegar, and sugar Fruits - Think berries, peaches, plums, pears, cherries and many other fruits, just make sure they are wonderfully ripe and sweet. The fruits need to be washed, peeled, chopped, or lightly crushed. Some additions can be ginger, citrus peels, or even peppercorns. Vinegar – you can use distilled white vinegar, apple cider vinegar, or even wine vinegars. -

Native Shrubs

Native Shrubs Downy Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea) Grows from 10 to 25 feet high with a spread of 12 feet. A deciduous tree that prefers rich loamy soil but will grow well in clay or any soil that has moderate moisture. White showy flowers bloom in early to mid spring and are followed by dark red to purple edible berries. Zones 4 - 9. Shadblow Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) Grows from 25 to 30 feet high with a spread of 15 to 20 feet. Grows best in medium wet, well-drained soil but will tolerate a wide range. Prefers partial shade to full sun. Clusters of white flowers are followed by edible red/purple berries in late summer. Zones 4-8 Allegheny Serviceberry (Amelancheir laevis) Grows to approximately 25 feet high with a spread of 20 feet. Grows in shade and partial shade and prefers moist soils. A hardy serviceberry species that will tolerate more moisture and light then some other varieties. White flowers and purple/black edible berries are typical. Zones 4-8. Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) Grows from 6 to 30 inches high with a spread of 3 feet. Leaves are narrow, evergreen and leathery with a blue-green color. Some resemblance to the culinary herb. Typically found in northern bogs and marshes. Flowers are small, pink, and bell- shaped. Grows best in very moist, acidic soil in cooler climates. Zones 2- 6. Black Chokeberry (Aronia melancarpa) Can grow up to 8 feet high with a spread of 8 feet. Grows best in moist, well-drained, acidic soils but will tolerate drier sandy soils or wet clayey ones. -

Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity Second Edition Revised Of: A.C

Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Second edition revised of: A.C. Zeven and P.M. Zhukovsky, 1975, Dictionary of cultivated plants and their centres of diversity 'N -'\:K 1~ Li Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Excluding most ornamentals, forest trees and lower plants A.C. Zeven andJ.M.J, de Wet K pudoc Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation Wageningen - 1982 ~T—^/-/- /+<>?- •/ CIP-GEGEVENS Zeven, A.C. Dictionary ofcultivate d plants andthei rregion so f diversity: excluding mostornamentals ,fores t treesan d lowerplant s/ A.C .Zeve n andJ.M.J ,d eWet .- Wageninge n : Pudoc. -11 1 Herz,uitg . van:Dictionar y of cultivatedplant s andthei r centreso fdiversit y /A.C .Zeve n andP.M . Zhukovsky, 1975.- Me t index,lit .opg . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 SISO63 2UD C63 3 Trefw.:plantenteelt . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 ©Centre forAgricultura l Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen,1982 . Nopar t of thisboo k mayb e reproduced andpublishe d in any form,b y print, photoprint,microfil m or any othermean swithou t written permission from thepublisher . Contents Preface 7 History of thewor k 8 Origins of agriculture anddomesticatio n ofplant s Cradles of agriculture and regions of diversity 21 1 Chinese-Japanese Region 32 2 Indochinese-IndonesianRegio n 48 3 Australian Region 65 4 Hindustani Region 70 5 Central AsianRegio n 81 6 NearEaster n Region 87 7 Mediterranean Region 103 8 African Region 121 9 European-Siberian Region 148 10 South American Region 164 11 CentralAmerica n andMexica n Region 185 12 NorthAmerica n Region 199 Specieswithou t an identified region 207 References 209 Indexo fbotanica l names 228 Preface The aimo f thiswor k ist ogiv e thereade r quick reference toth e regionso f diversity ofcultivate d plants.Fo r important crops,region so fdiversit y of related wild species areals opresented .Wil d species areofte nusefu l sources of genes to improve thevalu eo fcrops . -

A Field Guide to Selected Trees and Shrubs of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Campus

A Field Guide to Selected Trees and Shrubs of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Campus Written and Illustrated by: Richard H. Uva Class of 1991 Department of Biology Univeristy of Massachusetts Dartmouth North Dartmouth, MA Edited by: James R. Sears Professor of Biology University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Converted to Web Format by: Sustainability Studies Seminar Class Spring 2012 University of Massachusetts Dartmouth 1 Table of Contents RED MAPLE Ȃ ACER RUBRUM ............................................................................................................. 4 YELLOW BIRCH - BETULA LUTEA ...................................................................................................... 6 GRAY BIRCH - BETULA POPULIFOLIA .............................................................................................. 8 SWEET PEPPERBUSH - CLETHRA ALNIFOLIA .............................................................................. 10 SWEETFERN - COMPTONIA PEREGRINE ........................................................................................ 11 FLOWERING DOGWOOD - CORNUS FLORIDA .............................................................................. 13 AMERICAN BEECH - FAGUS GRANDIFOLIA ................................................................................... 15 WITCH-HAZEL - HAMAMELIS VIRGINIANA ................................................................................... 17 INKBERRY - ILEX GLABRA ................................................................................................................ -

We Hope You Find This Field Guide a Useful Tool in Identifying Native Shrubs in Southwestern Oregon

We hope you find this field guide a useful tool in identifying native shrubs in southwestern Oregon. 2 This guide was conceived by the “Shrub Club:” Jan Walker, Jack Walker, Kathie Miller, Howard Wagner and Don Billings, Josephine County Small Woodlands Association, Max Bennett, OSU Extension Service, and Brad Carlson, Middle Rogue Watershed Council. Photos: Text: Jan Walker Max Bennett Max Bennett Jan Walker Financial support for this guide was contributed by: • Josephine County Small • Silver Springs Nursery Woodlands Association • Illinois Valley Soil & Water • Middle Rogue Watershed Council Conservation District • Althouse Nursery • OSU Extension Service • Plant Oregon • Forest Farm Nursery Acknowledgements Helpful technical reviews were provided by Chris Pearce and Molly Sullivan, The Nature Conservancy; Bev Moore, Middle Rogue Watershed Council; Kristi Mergenthaler and Rachel Showalter, Bureau of Land Management. The format of the guide was inspired by the OSU Extension Service publication Trees to Know in Oregon by E.C. Jensen and C.R. Ross. Illustrations of plant parts on pages 6-7 are from Trees to Know in Oregon (used by permission). All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Book formatted & designed by: Flying Toad Graphics, Grants Pass, Oregon, 2007 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 4 Plant parts ................................................................................... 6 How to use the dichotomous keys ........................................... -

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Contents White / Cream ................................ 2 Grasses ...................................... 130 Yellow ..........................................33 Rushes ....................................... 138 Red .............................................63 Sedges ....................................... 140 Pink ............................................66 Shrubs / Trees .............................. 148 Blue / Purple .................................83 Wood-rushes ................................ 154 Green / Brown ............................. 106 Indexes Aquatics ..................................... 118 Common name ............................. 155 Clubmosses ................................. 124 Scientific name ............................. 160 Ferns / Horsetails .......................... 125 Appendix .................................... 165 Key Traffic light system WF symbol R A G Species with the symbol G are For those recording at the generally easier to identify; Wildflower Level only. species with the symbol A may be harder to identify and additional information is provided, particularly on illustrations, to support you. Those with the symbol R may be confused with other species. In this instance distinguishing features are provided. Introduction This guide has been produced to help you identify the plants we would like you to record for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme. There is an index at -

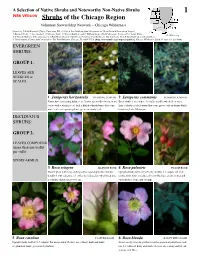

Shrubs of the Chicago Region

A Selection of Native Shrubs and Noteworthy Non-Native Shrubs 1 WEB VERSION Shrubs of the Chicago Region Volunteer Stewardship Network – Chicago Wilderness Photos by: © Paul Rothrock (Taylor University, IN), © John & Jane Balaban ([email protected]; North Branch Restoration Project), © Kenneth Dritz, © Sue Auerbach, © Melanie Gunn, © Sharon Shattuck, and © William Burger (Field Museum). Produced by: Jennie Kluse © vPlants.org and Sharon Shattuck, with assistance from Ken Klick (Lake County Forest Preserve), Paul Rothrock, Sue Auerbach, John & Jane Balaban, and Laurel Ross. © Environment, Culture and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [http://www.fmnh.org/temperateguides/]. Chicago Wilderness Guide #5 version 1 (06/2008) EVERGREEN SHRUBS: GROUP 1. LEAVES ARE NEEDLES or SCALES. 1 Juniperus horizontalis TRAILING JUNIPER: 2 Juniperus communis COMMON JUNIPER: Plants have a creeping habit; some leaves are needles but most are Erect shrub or tree (up to 3 m tall); needles whorled on stem; scales with a whitish coat; fruit a bluish-whitish berry-like cone; fruit a bluish or black berry-like cone; grows only in dunes/bluffs male cones on separate plants; grows in sandy soils. bordering Lake Michigan. DECIDUOUS SHRUBS: GROUP 2. LEAVES COMPOUND (more than one leaflet per stalk). STEMS ARMED. 3 Rosa setigera ILLINOIS ROSE: 4 Rosa palustris SWAMP ROSE: Mature plant with long-arching stems; sparse prickles; leaflets Upright shrub; stems very thorny; leaflets 5-7; sepals fall from usually 3, but sometimes 5; styles (female pollen tube) fused into mature fruit; fruit smooth, red berry-like hips; grows in wet and a column; stipules narrow to tip. open ditches, bogs, and swamps. -

Nr 222 Native Tree, Shrub, & Herbaceous Plant

NR 222 NATIVE TREE, SHRUB, & HERBACEOUS PLANT IDENTIFICATION BY RONALD L. ALVES FALL 2014 NR 222 by Ronald L. Alves Note to Students NOTE TO STUDENTS: THIS DOCUMENT IS INCOMPLETE WITH OMISSIONS, ERRORS, AND OTHER ITEMS OF INCOMPETANCY. AS YOU MAKE USE OF IT NOTE THESE TRANSGRESSIONS SO THAT THEY MAY BE CORRECTED AND YOU WILL RECEIVE A CLEAN COPY BY THE END OF TIME OR THE SEMESTER, WHICHEVER COMES FIRST!! THANKING YOU FOR ANY ASSISTANCE THAT YOU MAY GIVE, RON ALVES. Introduction This manual was initially created by Harold Whaley an MJC Agriculture and Natural Resources instruction from 1964 – 1992. The manual was designed as a resource for a native tree and shrub identification course, Natural Resources 222 that was one of the required courses for all forestry and natural resource majors at the college. The course and the supporting manual were aimed almost exclusively for forestry and related majors. In addition to NR 222 being taught by professor Whaley, it has also been taught by Homer Bowen (MJC 19xx -), Marlies Boyd (MJC 199X – present), Richard Nimphius (MJC 1980 – 2006) and currently Ron Alves (MJC 1974 – 2004). Each instructor put their own particular emphasis and style on the course but it was always oriented toward forestry students until 2006. The lack of forestry majors as a result of the Agriculture Department not having a full time forestry instructor to recruit students and articulate with industry has resulted in a transformation of the NR 222 course. The clientele not only includes forestry major, but also landscape designers, environmental horticulture majors, nursery people, environmental science majors, and people interested in transforming their home and business landscapes to a more natural venue.