LGBTQ+ in Schools Subtitle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Final Version

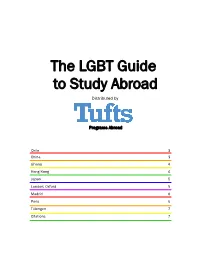

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out. -

Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest

Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest Religion Yet, while the Constitution protects the right of people to continue with such beliefs, it does not allow the state to turn these beliefs – even in moderate or gentle versions – into dogma imposed on the whole of society. Contents South African Constitutional Court, 19981 Overview 4 Religion and proportionality 11 Religion and government policy 21 Statements from religious leaders on LGBT matters 25 Conclusion 31 Appendix 32 This is one in a series of notes produced for the Human Dignity Trust on the criminalisation of homosexuality and good governance. Each note in the series discusses a different aspect of policy that is engaged by the continued criminalisation of homosexuality across the globe. The Human Dignity Trust is an organisation made up of international lawyers supporting local partners to uphold human rights and constitutional law in countries where private, consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex is criminalised. We are a registered charity no.1158093 in England & Wales. All our work, whatever country it is in, is strictly not-for-profit. 1 National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Another v Minister of Justice and Others [1998] ZACC 15 (Constitutional Court), para. 137. 2 3 Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest Religion Overview 03. The note then examines whether, as a The origin of modern laws that expanding Empire in Asia, Africa and the matter of international human rights law, Pacific. For instance, the Indian Penal Code 01. Consensual sex between adults of the adherence to religious doctrine has any criminalise homosexuality of 1860 made a crime of ‘carnal knowledge same-sex is a crime in 78 jurisdictions.2 bearing on whether the state is permitted to 05. -

Newsletter Issue 16 Summer 2012

OLGA NEWSLETTER ISSUE 16 June-July-August 2012 OLGA Useful contact information Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Trans Association A Community Network SEXUALITY Albion Pub & Cabaret PO Box 458 Scarborough YO11 9EH Telephone: 07929 465044 136 Castle Road, Scarborough Tel: 01723 379068 OLGA Tel: 07929 465 044 Email: [email protected] www.olga.uk.com Email: [email protected] www.olga.uk.com Gay Scarborough Tel: 01723 375 849 Newsletter Issue 16 June-July-August 2012 P0 Box 458, Scarborough YO11 9EH Bacchus Night Club Tel: 01723 373 689 MESMAC Yorkshire. Tel: 01904 620 400 7a Ramshill Road, Scarborough YO11 P0 Box 549, York. Y030 7GX York Lesbian Social Group 18+ Tel: 07963 414434 MENTAL HEALTH Email: [email protected] OLGA’s successes GENERAL ADVICE Crisis Call Tel: 0800 501 254 (telephone support) One or two particular successes care homes, which makes our 01723 384644 (crisis response, resolution and Customer First Tel: 01723 232 323 need to be highlighted. work extremely valuable and home treatment) (Free from landlines. Mobiles - Scarborough Borough Council (General Enquiries) Firstly, our work is being needed. We believe that Peter cost for initial message and Crisis Call will call St. Nicholas Street, Scarborough YO11 2HG researched and will be Tatchell has begun to be you back, which is free) OLGA TeI: 07929 465 044 Summer has arrived, after a published by a senior involved in olgbt care issues. Great. We need his strong Samaritans Tel: 01723 368 888 Email: [email protected] long drawn out wet Spring. So, researcher from Nottingham voice. Samaritan House, 40 Trafalgar Street West, P0 Box 458, Scarborough YO11 9EH we hope our readers can enjoy University, End-of-life and Scarborough YO12 7AS Age UK Scarborough Tel: 01723379058 more outdoor activities and get Palliative Care Department. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of Journal Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of journal stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. Latest highlights (17-23 Sep): ● Launch of BMJ’s new journal General Psychiatry was covered by trade outlet InPublishing ● A study in The BMJ showing a link between a high-gluten diet in pregnancy and child diabetes generated widespread coverage, including the The Guardian, Hindustan Times, and 100+ mentions in UK local newspapers ● Two studies in BMJ Open generated global news headlines this week - high sugar content of most supermarket yogurts and air pollution linked to heightened dementia risk. Coverage included ABC News, CNN, Newsweek, Beijing Bulletin and 200+ mentions in UK local print and broadcast outlets BMJ BMJ to publish international psychiatry journal - InPublishing 19/09/2018 British Journalism Awards for Specialist Media 2018: Winners announced (Gareth Iacobucci winner) InPublishing 20/09/18 The BMJ Analysis: Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis ‘Latent’ Tuberculosis? It’s Not That Common, Experts Find - New York Times 20/09/2018 Also covered by: Business Standard, The Hindu iMedicalApps: This Week's Top Picks: The BMJ - MedPage Today 21/09/2018 Also covered by: Junkies Tech Research: Association between maternal gluten intake and type 1 diabetes in offspring: national prospective cohort study in Denmark Eating lots of pasta during pregnancy doubles the risk of children getting Type 1 diabetes by -

Pakistan: Treatment of Sexual and Gender Minorities by Society And

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 34 Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links • Advanced search help 17 January 2019 PAK106219.E Pakistan: Treatment of sexual and gender minorities by society and authorities; state protection and support services available (2017-January 2019) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Legislation and Enforcement For information on legislation t( at prohibits same-sex sexual acts between men in Pakistan, see Response to Information Request PAK104712 of January 2014. According to sources, under Sharia law, homosexuals face the death penalty in Pakistan (AFP 29 Oct. 2018; Pakistan 2018). https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=457702&pls=1 2/9/2019 Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 2 of 34 In a May 2017 report, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) reports that documented arrests of homosexuals in Pakistan have occurred in the past three years (ILGA May 2017, 194). Other sources indicate that same-sex sexual acts are "rarely" prosecuted in Pakistan (US 20 Apr. -

Section 28 Page 1 Section 28

Section 28 Page 1 Section 28 Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 was a controversial amendment to the UK's Local Government Act 1986, enacted on 24 May 1988 and repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of the UK by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003. The amendment stated that a local authority "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship". Some people believed that Section 28 prohibited local councils from distributing any material, whether plays, leaflets, books, etc, that portrayed gay relationships as anything other than abnormal. Teachers and educational staff in some cases were afraid of discussing gay issues with students for fear of losing state funding. Because it did not create a criminal offence, no prosecution was ever brought under this provision, but its existence caused many groups to close or limit their activities or self- censor. For example, a number of lesbian, gay, transgender, and bisexual student support groups in schools and colleges across Britain were closed due to fears by council legal staff that they could breach the Act. While going through Parliament, the amendment was constantly relabelled with a variety of clause numbers as other amendments were added to or deleted from the Bill, but by the final version of the Bill, which received Royal Assent, it had become Section 28. Section 28 is sometimes referred to as Clause 28. -

The Hidden Knots of Gay Marriage

The ‘Ties that Bind Us’: The Hidden Knots of Gay Marriage Bronwyn Winter, University of Sydney Conservatives believe in the ties that bind us; that society is stronger when we make vows to each other and support each other. So I don’t support gay marriage despite being a Conservative. I support gay marriage because I’m a Conservative. (David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Keynote Speech at Conservative Party National Conference, Manchester, 5 October 2011). Gay marriage has become a major transnational gay rights issue. It is considered a key marker of equal citizenship between gay and straight individuals: a step forward in the normalisation and thus de-stigmatisation of homosexuality. As Lisa Duggan has put it, ‘marriage equality has become the singularly representative issue for the mainstream LGBT rights movement, often standing in for all the political aspirations of queer people’ (Duggan 2011: 1). The proposition that legalisation of gay marriage represents progress is assumed to be self-evident. Scholarship over the last two decades, however (such as Polikoff 1993; Duggan 2003; Ahmed 2006; Puar 2006; Browne 2011; Halberstam 2012), has challenged that assumption, and Puar in particular has noted that this ‘progress’ is concurrent with other forms of exclusion. In this article I will further explore these challenges in considering how states have used gay marriage to enhance their social-justice credentials and popularity while leaving other social justice issues, including some gay rights issues, unaddressed. I argue that gay marriage is a convenient liberal smokescreen that, in reassuring progressive elites (straight and gay), deflects the PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. -

LGBT Student Guide for Education Abroad Table of Contents Why This Guide Was Made: a Note from the Author 2

LGBT Student Guide for Education Abroad Table of Contents Why This Guide Was Made: A Note From The Author 2 General Things to Consider 3 Global Resources 5 Internet Resources 5 Print Resources 5 Region and Country Narratives and Resources 6 Africa 6 Ghana 7 Pacifica 8 Australia 8 Asia 9 China 9 India 10 Japan 11 South Korea 12 Malaysia 13 Europe 14 Czech Republic 14 Denmark 15 France 16 Germany 17 Greece 18 Italy 19 Russia 20 Slovakia 21 Spain 22 Sweden 23 United Kingdom 24 The Americas 25 Argentina 25 Bolivia 26 Brazil 27 Canada 28 Costa Rica 29 Honduras 30 Mexico 31 Panama 32 Peru 33 1 Why This Guide Was Made A Note From The Author Kristen Shalosky In order to tell you how and why this guide was made, I must first give you some background on myself. I attended USF as an undergraduate student of the College of Business and the Honors College from Fall 2006 to Spring 2010. During that time, I became very involved with the LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) advocacy movements on campus, including being President of the PRIDE Alliance for a year. When I was told that the Education Abroad department was looking for an Honors Thesis candidate to help find ways to make the department and its programs more LGBT-friendly, it seemed like a natural choice. As I conducted my research, I realized that there are some things that LGBT students need to consider before traveling abroad that other students don’t. Coming out as an LGBT student abroad can be much different than in the U.S.; in extreme cases, the results of not knowing cultural or legal standards can be violence or imprisonment. -

Exploring Social Representations of LGBTQ+ Law And

“We still have a long way to go”: Exploring Social Representations of LGBTQ+ Law and Equality through Mixed Qualitative Methods Annabel D. Roberts Keele University Katie Wright-Bevans Keele University Abstract In the wake of a changing global context for the LGBTQ+ community and equality, it has become increasingly important to bridge the gap between psychology and politics. The present study achieved this by exploring understandings of the current and future state of legal equality for the LGBTQ+ community, using social representations theory and a politically-charged thematic analysis. Talk from three different groups were analysed: (1) government actors, (2) hetero-cisgender people and (3) LGBTQ+ identifying individuals. Analysis of data from these three samples allowed for an exploration into differences in power in society may impact the representational field. Overall, three themes were identified, with their respective social representations; (1) progress vs “a long way to go”, with an emphasis on (2) responsibility and (3) LGB triumphalism vs T. All of which are underpinned by the thema of us vs them. Overall, the present study aimed to counteract individualistic conceptualisations of LGBTQ+ oppression by exploring how social representations of law, at a meso-level, can be used to understand the issue in context while recommending possible avenues for social change, to ultimately bridge the gap between psychology and politics. Keywords: social representations, social change, power, sexuality, equality. i Social Representations of LGBTQ+ Law and Equality Currently, in the UK, despite the growing rhetoric that LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and others) individuals are equal to those of heterosexual, cisgender people (Ibhawoh, 2014) and positive law reforms such as the same-sex couples act (GOV.UK, 2013), LGBTQ+ inequality is rampant. -

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression

Country Policy and Information Note Uganda: Sexual orientation and gender identity and expression Version 4.0 April 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

The Politics of Eradication and the Future of Lgbt Rights

THE POLITICS OF ERADICATION AND THE FUTURE OF LGBT RIGHTS NANCY J. KNAUER* ABSTRACT The debate over LGBT rights has always been a debate over the right of LGBT people to exist. This Article explores the politics of eradication and the institutional forces that are brought to bear on LGBT claims for visibility, rec- ognition, and dignity. In its most basic form, the desire to eradicate LGBT identities ®nds expression in efforts to ªcureº or ªconvertº LGBT people, espe- cially LGBT youth. It is also re¯ected in present-day policy initiatives, such as the recent wave of anti-LGBT legislation that has been introduced in states across the country. The politics of eradication has prompted the Trump admin- istration to reverse many Obama-era initiatives that recognized and protected LGBT people. It is also at the heart of a proposal to promulgate a federal de®- nition of gender that could remove any acknowledgment of transgender people from federal programs and civil rights protections. This Article is divided into three sectionsÐeach uses a distinct institutional lens: science, law, and religion. The ®rst section engages the ®eld of science, which helped produce the initial iterations of LGBT identity. It charts the evolu- tion of scienti®c theories regarding LGBT people and places a special emphasis on how these theories were used to further both LGBT subordination and liber- ation. The second section shifts the focus to the legal battles over LGBT rights that began in the 1990s at approximately the same time the scienti®c community started its exploration of the biological underpinnings of LGBT identities.