Parliamentary Questions As Instruments of Substantive Representation: an Analysis of the 2005-2010 Parliament1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Think of the Consequences

NHSCA EDITORIAL September 2014 Think of the consequences This July, a passenger aircraft was shot down such clinics are usually staffed by GPs with a over Ukraine by a ground–to–air missile which, Special Interest (GPSIs), many of whom do not it seems likely, was provided to one of the fulfil the supposedly mandatory experience armed groups in the area by a third party. This and training criteria for such posts. David Eedy appalling event raises many issues, including points out that the use of these ‘community’ the immorality of the arms trade and the results clinics has never been shown to reduce hospital of interference in a neighbouring country’s waiting lists, they threaten to destabilise the territory and politics, and beyond this there are hospital service and they cost a lot more than the issues of unforeseen consequences. Those hospital clinics. The service thus provided is operating this complex modern equipment not acting as a useful filter to reduce hospital almost certainly had no intention of annihilating referrals and causes only delay in reaching a true 298 innocent travellers, neither, presumably, specialist service. Further, we cannot ignore the did the providers think they might. It seems inevitable impact of this continued outsourcing likely that inadequate training, against a on education of students and trainees as the background of inexperience of such dangerous service is fragmented. At a recent public equipment, resulted in this disaster. Unforeseen, meeting a woman who had attended a local but not unforeseeable. private sector dermatology clinic told us that she could not fault the service - everyone was very Nearer to home, we are increasingly aware of professional and the surroundings pleasant - decisions about clinical services made by those except that they could not deal with her problem who know little about them, do not wish to look and she had to be referred on to the hospital. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Eukropean Movement HKCF Newsletter January 2018

European Movement in Hammersmith, Kensington, Chelsea & Fulham News No. 5 – January 2018 WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR WHERE to FInd us New Year greetings to EM members, Question your MEPs https://emhkcf.nationbuilder.com associates and all those ready to What are they doing www.facebook.com/emhkcf pass the time of day with us. about Brexit? 25 January 19.00 MEPs have an important place in the @emhkcf This is a crucial year for all who care politics of Brexit. Under the Treaty of [email protected] about our European membership Lisbon, the European Council needs COMMITTEE and who, for many reasons dread to obtain the European Parliament’s Chair – Anne Corbett. being cut out of the EU. consent before it can conclude the [email protected] In May there are the local elections UK/EU27 withdrawal agreement. Secretary – Mike Vessey in which EU citizens have the right They have already reacted with their [email protected] to vote. In October, the UK and EU ‘red lines’. Might they scupper the final Treasurer & Membership institutions aim to have an outline deal (if there is one)? Or will they try to Secretary – Clare Singleton. agreement for the UK’s withdrawal reform it? [email protected] from the EU on the still unknown We are pleased to welcome a cross- Local campaigners terms as to whether we are heading party group of MEPs and former Hammersmith – Keith Mallinson for a ‘hard’ or a soft’ Brexit. And MP to our panel discussion tonight, Kensington – Virginie Dhouibi before March 29, 2019, there needs chaired by Denis MacShane, former Chelsea & Fulham – Christo to be a political agreement between Minister for Europe. -

![[2019] CSOH 68 P680/19 OPINION of LORD DOHERTY in the Petition](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0061/2019-csoh-68-p680-19-opinion-of-lord-doherty-in-the-petition-1670061.webp)

[2019] CSOH 68 P680/19 OPINION of LORD DOHERTY in the Petition

OUTER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION [2019] CSOH 68 P680/19 OPINION OF LORD DOHERTY In the petition (FIRST) JOANNA CHERRY QC MP, (SECOND) JOLYON MAUGHAM QC, (THIRD) JOANNE SWINSON MP, (FOURTH) IAN MURRAY MP, (FIFTH) GERAINT DAVIES MP, (SIXTH) HYWEL WILLIAMS MP, (SEVENTH) HEIDI ALLEN MP, (EIGHTH) ANGELA SMITH MP, (NINTH) THE RT HON PETER HAIN, THE LORD HAIN OF NEATH, (TENTH) JENNIFER JONES, THE BARONESS JONES OF MOULESCOOMB, (ELEVENTH) THE RT HON JANET ROYALL, THE BARONESS ROYALL OF BLAISDON, (TWELFTH) ROBERT WINSTON, THE LORD WINSTON OF HAMMERSMITH, (THIRTEENTH) STEWART WOOD, THE LORD WOOD OF ANFIELD, (FOURTEENTH) DEBBIE ABRAHAMS MP, (FIFTEENTH) RUSHANARA ALI MP, (SIXTEENTH) TONIA ANTONIAZZI MP, (SEVENTEENTH) HANNAH BARDELL MP, (EIGHTEENTH) DR ROBERTA BLACKMAN-WOODS MP, (NINETEENTH) BEN BRADSHAW MP, (TWENTIETH) THE RT HON TOM BRAKE MP, (TWENTY-FIRST) KAREN BUCK MP, (TWENTY-SECOND) RUTH CADBURY MP,(TWENTY-THIRD) MARSHA DE CORDOVA MP, (TWENTY-FOURTH) RONNIE COWAN MP, (TWENTY-FIFTH) NEIL COYLE MP, (TWENTY-SIXTH) STELLA CREASY MP, (TWENTY-SEVENTH) WAYNE DAVID MP, (TWENTY-EIGHTH) EMMA DENT COAD MP, (TWENTY-NINTH) STEPHEN DOUGHTY MP, (THIRTIETH) ROSIE DUFFIELD MP, (THIRTY-FIRST) JONATHAN EDWARDS MP, (THIRTY-SECOND) PAUL FARRELLY MP, (THIRTY-THIRD) JAMES FRITH MP, (THIRTY-FOURTH) RUTH GEORGE MP, (THIRTY-FIFTH) STEPHEN GETHINS MP, (THIRTY-SIXTH) PREET KAUR GILL MP, (THIRTY-SEVENTH) PATRICK GRADY MP, (THIRTY-EIGHTH) KATE GREEN MP, (THIRTY-NINTH) LILIAN GREENWOOD MP, (FORTIETH) JOHN GROGAN MP, (FORTY-FIRST) HELEN HAYES MP, (FORTY- SECOND) WERA HOBHOUSE MP, (FORTY-THIRD) THE RT HON DAME MARGARET HODGE MP, (FORTY-FOURTH) DR RUPA HUQ MP, (FORTY-FIFTH) RUTH JONES MP, (FORTY-SIXTH) GED KILLEN MP, (FORTY-SEVENTH) PETER KYLE MP, (FORTY- EIGHTH) BEN LAKE MP, (FORTY-NINTH) THE RT HON DAVID LAMMY MP, (FIFTIETH) CLIVE LEWIS MP, (FIFTY-FIRST) KERRY MCCARTHY MP, (FIFTY-SECOND) 2 STUART C. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 635 1 February 2018 No. 90 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 1 February 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 953 1 FEBRUARY 2018 954 Mr Walker: The Government have been talking to a House of Commons wide range of industry groups and representative bodies of business, and we recognise that there are benefits in some areas of maintaining regulatory alignment and Thursday 1 February 2018 ensuring that we have the most frictionless access to European markets. Of course we are entering the The House met at half-past Nine o’clock negotiations on the future partnership, and we want to take the best opportunities to trade with Europe and the wider world. PRAYERS Mr Philip Hollobone (Kettering) (Con): Is it true that Michel Barnier has basically offered us the Canada [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] model, agreement on which could be reached this year, thus negating the need for any transition period? Mr Walker: The Government’s policy is that we are Oral Answers to Questions pursuing a bespoke trade agreement, not an off-the-shelf model. We believe that it will be in the interests of both sides in this negotiation to secure an implementation period. EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION Stephen Timms (East Ham) (Lab): The European The Secretary of State was asked— Union has clearly and firmly set out its views on the options for these negotiations. Ministers so far have Regulatory Equivalence signally failed to provide any coherent response because they cannot agree among one another, and the Minister’s 1. -

Urgent Open Letter to Jesse Norman Mp on the Loan Charge

URGENT OPEN LETTER TO JESSE NORMAN MP ON THE LOAN CHARGE Dear Minister, We are writing an urgent letter to you in your new position as the Financial Secretary to the Treasury. On the 11th April at the conclusion of the Loan Charge Debate the House voted in favour of the motion. The Will of the House is clearly for an immediate suspension of the Loan Charge and an independent review of this legislation. Many Conservative MPs have criticised the Loan Charge as well as MPs from other parties. As you will be aware, there have been suicides of people affected by the Loan Charge. With the huge anxiety thousands of people are facing, we believe that a pause and a review is vital and the right and responsible thing to do. You must take notice of the huge weight of concern amongst MPs, including many in your own party. It was clear in the debate on the 4th and the 11th April, that the Loan Charge in its current form is not supported by a majority of MPs. We urge you, as the Rt Hon Cheryl Gillan MP said, to listen to and act upon the Will of the House. It is clear from their debate on 29th April that the House of Lords takes the same view. We urge you to announce a 6-month delay today to give peace of mind to thousands of people and their families and to allow for a proper review. Ross Thomson MP John Woodcock MP Rt Hon Sir Edward Davey MP Jonathan Edwards MP Ruth Cadbury MP Tulip Siddiq MP Baroness Kramer Nigel Evans MP Richard Harrington MP Rt Hon Sir Vince Cable MP Philip Davies MP Lady Sylvia Hermon MP Catherine West MP Rt Hon Dame Caroline -

London's Political

CONSTITUENCY MP (PARTY) MAJORITY Barking Margaret Hodge (Lab) 15,272 Battersea Jane Ellison (Con) 7,938 LONDON’S Beckenham Bob Stewart (Con) 18,471 Bermondsey & Old Southwark Neil Coyle (Lab) 4,489 Bethnal Green & Bow Rushanara Ali (Lab) 24,317 Bexleyheath & Crayford David Evennett (Con) 9,192 POLITICAL Brent Central Dawn Butler (Lab) 19,649 Brent North Barry Gardiner (Lab) 10,834 Brentford & Isleworth Ruth Cadbury (Lab) 465 Bromley & Chislehurst Bob Neill (Con) 13,564 MAP Camberwell & Peckham Harriet Harman (Lab) 25,824 Carshalton & Wallington Tom Brake (LD) 1,510 Chelsea & Fulham Greg Hands (Con) 16,022 This map shows the political control Chingford & Woodford Green Iain Duncan Smith (Con) 8,386 of the capital’s 73 parliamentary Chipping Barnet Theresa Villiers (Con) 7,656 constituencies following the 2015 Cities of London & Westminster Mark Field (Con) 9,671 General Election. On the other side is Croydon Central Gavin Barwell (Con) 165 Croydon North Steve Reed (Lab [Co-op]) 21,364 a map of the 33 London boroughs and Croydon South Chris Philp (Con) 17,410 details of the Mayor of London and Dagenham & Rainham Jon Cruddas (Lab) 4,980 London Assembly Members. Dulwich & West Norwood Helen Hayes (Lab) 16,122 Ealing Central & Acton Rupa Huq (Lab) 274 Ealing North Stephen Pound (Lab) 12,326 Ealing, Southall Virendra Sharma (Lab) 18,760 East Ham Stephen Timms (Lab) 34,252 Edmonton Kate Osamor (Lab [Co-op]) 15,419 Eltham Clive Efford (Lab) 2,693 Enfield North Joan Ryan (Lab) 1,086 Enfield, Southgate David Burrowes (Con) 4,753 Erith & Thamesmead -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Wednesday Volume 652 16 January 2019 No. 235 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 16 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1143 16 JANUARY 2019 1144 12. Marion Fellows (Motherwell and Wishaw) (SNP): House of Commons What recent discussions he has had with the Home Secretary on the potential effect on Scotland of UK Wednesday 16 January 2019 immigration policy after the UK leaves the EU. [908517] 14. Drew Hendry (Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock Strathspey) (SNP): What recent discussions he has had with the Home Secretary on the potential effect on PRAYERS Scotland of UK immigration policy after the UK leaves the EU. [908519] [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] The Secretary of State for Scotland (David Mundell): This has been a momentous week for Andy Murray, so I Speaker’s Statement am sure you will agree, Mr Speaker, that it is appropriate that at this Scottish questions we acknowledge in this Mr Speaker: Order. Colleagues will no doubt have House Andy’s extraordinary contribution to British seen a number of images taken by Members of scenes in sport, and his personal resilience and courage, and the Division Lobby last night. I would like to remind all express our hope that we will once again see Andy Murray colleagues that, as the recently issued guide to the rules on court. of behaviour and courtesies of the House makes explicitly I am in regular contact with the Home Secretary on a clear, Members range of issues of importance to Scotland, including “must not use any device to take photographs, film or make audio future immigration policy after the UK leaves the European recordings in or around the Chamber.” Union. -

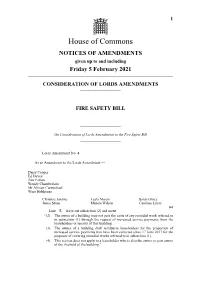

1 Notices of Amendments

1 House of Commons NOTICES OF AMENDMENTS given up to and including Friday 5 February 2021 CONSIDERATION OF LORDS AMENDMENTS FIRE SAFETY BILL On Consideration of Lords Amendments to the Fire Safety Bill Lords Amendment No. 4 As an Amendment to the Lords Amendment:— Daisy Cooper Ed Davey Tim Farron Wendy Chamberlain Mr Alistair Carmichael Wera Hobhouse Christine Jardine Layla Moran Sarah Olney Jamie Stone Munira Wilson Caroline Lucas (e) Line 5, leave out subsection (2) and insert— “(2) The owner of a building may not pass the costs of any remedial work referred to in subsection (1) through the request of increased service payments from the leaseholders or tenants of that building. (3) The owner of a building shall reimburse leaseholders for the proportion of increased service payments that have been collected since 17 June 2017 for the purposes of covering remedial works referred to in subsection (1). (4) This section does not apply to a leaseholder who is also the owner or part owner of the freehold of the building.” 2 Consideration of Lords Amendments: 5 February 2021 Fire Safety Bill, continued Stephen McPartland Royston Smith Mr Philip Hollobone Mr John Baron Caroline Nokes Bob Blackman Richard Graham Damian Green Anne Marie Morris Tom Tugendhat Andrew Selous Tom Hunt Sir David Amess Andrew Rosindell Henry Smith Sir Robert Neill Nick Fletcher Elliot Colburn Sir Mike Penning Mr William Wragg Mr Virendra Sharma Stephen Hammond David Warburton Richard Fuller Sir Roger Gale Tracey Crouch Paul Blomfield Dr Matthew Offord Mr Andrew Mitchell Hilary Benn Rebecca Long Bailey Caroline Lucas Dame Margaret Hodge Martin Vickers Sir Peter Bottomley Dawn Butler Kate Osamor Mrs Pauline Latham Shabana Mahmood Sarah Olney John Cryer Bell Ribeiro-Addy Derek Twigg Florence Eshalomi Chris Green Ms Harriet Harman Meg Hillier To move, That this House disagrees with the Lords in their Amendment. -

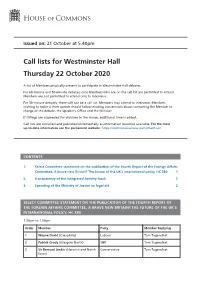

Call List for Thu 22 Oct 2020

Issued on: 21 October at 5.40pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Thursday 22 October 2020 A list of Members physically present to participate in Westminster Hall debates. For 60-minute and 90-minute debates, only Members who are on the call list are permitted to attend. Members are not permitted to attend only to intervene. For 30-minute debates, there will not be a call list. Members may attend to intervene. Members wishing to make a short speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Select Committee statement on the publication of the Fourth Report of the Foreign Affairs Committee, A brave new Britain? The future of the UK’s international policy, HC 380 1 2. Transparency of the Integrated Activity Fund 2 3. Spending of the Ministry of Justice on legal aid 2 SELECT COMMITTEE STATEMENT ON THE PUBLICATION OF THE FOURTH REPORT OF THE FOREIGN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE, A BRAVE NEW BRITAIN? THE FUTURE OF THE UK’S INTERNATIONAL POLICY, HC 380 1.30pm to 1.50pm Order Member Party Member Replying 1 Wayne David (Caerphilly) Labour Tom Tugendhat 2 Patrick Grady (Glasgow North) SNP Tom Tugendhat 3 Sir Bernard Jenkin (Harwich and North Conservative Tom Tugendhat Essex) 2 Call lists for Westminster -

Raab Hints at Backing for Earls Court Residents in Battle Against Capco by David Parsleywed 21 February 2018

Raab hints at backing for Earls Court residents in battle against Capco By David ParsleyWed 21 February 2018 Housing minister Dominic Raab has backed local residents at Earls Court protesting against Capital & Counties’ (Capco) plans for two council estates by saying the developer should have “majority support” from residents for its plans at the £12bn scheme in west London. West Kensington and Gibbs Green residents arrive at Westminster to hear MPs discuss Capco’s proposals for Earls Court During a debate in Westminster on Tuesday Raab said: “Regeneration should have the support of a majority of the residents whose lives will be directly affected.” His statement brings central government into line with the mayor of London Sadiq Khan and the Labour Party, which have said that demolition of council estates should only proceed with majority resident support. The debate was arranged by Labour Hammersmith MP Andy Slaughter. He questioned CapCo’s commitment to the scheme following years of protests from the resident of the West Kensington and Gibbs Green council estates, which sit at the heart of the 77-acre project. “Property Week carried the story that CapCo, the promoter of the Earl’s Court development, is about to sell the Empress State building to the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime for around £240m,” said Slaughter in his opening remarks. “Throwing in the towel on Empress State is the clearest sign yet that not just the masterplan, but CapCo itself is in serious trouble and is seeking to cut and run to save its own skin.” Emma Dent Coad, the Labour MP for Kensington, then called for Raab to join in the calls for London mayor Khan to repeal CapCo’s planning permission on the entire scheme. -

New NHS Capital Funding - Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust

From the Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care 39 Victoria Street London SW1H 0EU 020 7210 4850 Bob Blackman MP, Harrow East Karen Buck MP, Westminster North Dawn Butler MP, Brent Central Ruth Cadbury MP, Brentford and Isleworth Emma Dent Coad MP, Kensington Mark Field MP, Cities of London and Westminster Barry Gardiner MP, Brent North Greg Hands MP, Chelsea and Fulham Nick Hurd MP, Ruislip, Northwood and Pinner Boris Johnson MP, Uxbridge and South Ruislip Mark Lancaster MP, Milton Keynes North John McDonnell MP, Hayes and Harlington Andy Slaughter MP, Hammersmith Iain Stewart MP, Milton Keynes South Gareth Thomas MP, Harrow West 7th December 2018 New NHS Capital Funding - Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust I am delighted to let you know that as part of our Long Term Plan for the NHS, the following investments will be made in your constituency. We strongly support our NHS and want to help it to be the best it can be. Today’s investment shows we are making reality of that support in your area. We are funding the Oak Tree Ward - Woodlands Mental Health Wards Reconfiguration, Hillingdon scheme with new investment of up to £0.502 million which will deliver single sex bedrooms on adult inpatient mental health wards at Oak Tree Ward. This is part of £1bn extra capital funding being announced across England. It comes on top of the £20.5bn per year extra funding for the NHS over the next five years - the longest and largest funding settlement in the NHS’s history.