A History of Drinking the Scottish Pub Since 1700

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the UK Wine Market: from Niche to Mass-Market Appeal

beverages Article The Evolution of the UK Wine Market: From Niche to Mass-Market Appeal Julie Bower Independent Scholar, Worcester WR1 3DG, UK; [email protected] Received: 4 October 2018; Accepted: 8 November 2018; Published: 12 November 2018 Abstract: This article is an historic narrative account of the emergence of the mass-market wine category in the UK in the post-World War II era. The role of the former vertically-integrated brewing industry in the early stages of development is described from the perspective of both their distributional effects and their new product development initiatives. Significant in the narrative is the story of Babycham, the UK’s answer to Champagne that was targeted to the new consumers of the 1950s; women. Then a specially-developed French wine, Le Piat D’Or, with its catchy advertising campaign, took the baton. These early brands were instrumental in extending the wine category, as beer continued its precipitous decline. That the UK is now one of the largest wine markets globally owes much to the success of these early brands and those that arrived later in the 1990s, with Australia displacing France as the source for mass-market appeal. Keywords: UK wine consumption; UK brewing industry; resource partitioning theory; targeted marketing 1. Introduction The evolution of wine consumption in the UK is described by important socio-economic trends in consumer behavior that emerged in the 1950s. This coincided with a growing awareness within the alcoholic beverages industry that there was the need for new product development to satisfy the increasingly sophisticated and aspirational consumer. -

Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic

Notes Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic 1. Caroline McCracken-Flesher, writing shortly before the latter film’s release, argues that it is, like the former, ‘still an outsider tale’; despite the emphasis on ‘Scottishness’ within these films, they could only emerge from outside Scotland. Caroline McCracken-Flesher (2012) The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 20. 2. Kirsty A. MacDonald (2009) ‘Scottish Gothic: Towards a Definition’, The Bottle Imp, 6, 1–2, p. 1. 3. Andrew Payne and Mark Lewis (1989) ‘The Ghost Dance: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, Public, 2, 60–73, p. 61. 4. Nicholas Royle (2003) The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 12. 5. Allan Massie (1992) The Hanging Tree (London: Mandarin), p. 61. 6. See Luke Gibbons (2004) Gaelic Gothic: Race, Colonization, and Irish Culture (Galway: Arlen House), p. 20. As Coral Ann Howells argues in a discussion of Radcliffe, Mrs Kelly, Horsley-Curteis, Francis Lathom, and Jane Porter, Scott’s novels ‘were enthusiastically received by a reading public who had become accustomed by a long literary tradition to associate Scotland with mystery and adventure’. Coral Ann Howells (1978) Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction (London: Athlone Press), p. 19. 7. Ann Radcliffe (1995) The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, ed. Alison Milbank (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 3. 8. As James Watt notes, however, Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne remains a ‘derivative and virtually unnoticed experiment’, heavily indebted to Clara Reeves’s The Old English Baron. James Watt (1999) Contesting the Gothic: Fiction, Genre and Cultural Conflict, 1764–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. -

Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Anymore?

Christopher Fevre 100009227 ‘Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Any More?’ Word Count: 4,290 Red Clydeside, described aptly by Maggie Craig as ‘those heady decades at the beginning of the twentieth century when passionate people and passionate politics swept like a whirlwind through Glasgow’ is arguably the most significant yet controversial subject in Scottish labour and social history.1 Yet, it is because of this controversy that questions still linger regarding the significance of Red Clydeside in the overall narrative of British and more specifically, Scottish history. The title of this paper, ‘Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Any More?’ has been generously borrowed from Terry Brotherstone’s interesting article in Militant Workers: Labour and Class Conflict on the Clyde 1900- 1950.2 Following a decade in which the legacy of the Red Clydesiders had been systematically attacked by revisionist historians agitated by contemporary attempts to link the events on the Clyde with those occurring in Russia in 1917, Brotherstone emphasised the new and developing common sense approach to the Red Clydeside debate. It was argued that ‘A new consensus seems to be emerging... which acknowledges the significance of the events associated with Red Clydeside, but seeks to dissociate them from what is now perceived as the ‘myth’ or ‘legend’ that they involved a revolutionary challenge to the British state’. However, as a consequence of the ever changing nature of Red Clydeside historiography it is now time for a re-assessment of the significance of Red Clydeside which incorporates new research into the rise of left-wing politics in Scotland more generally. -

126613742.23.Pdf

c,cV PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME XXV WARRENDER LETTERS 1935 from, ike, jxicUtre, in, ike, City. Chcomkers. Sdinburyk, WARRENDER LETTERS CORRESPONDENCE OF SIR GEORGE WARRENDER BT. LORD PROVOST OF EDINBURGH, AND MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE CITY, WITH RELATIVE PAPERS 1715 Transcribed by MARGUERITE WOOD PH.D., KEEPER OF THE BURGH RECORDS OF EDINBURGH Edited with an Introduction and Notes by WILLIAM KIRK DICKSON LL.D., ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1935 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Letters printed in this volume are preserved in the archives of the City of Edinburgh. Most of them are either written by or addressed to Sir George Warrender, who was Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1713 to 1715, and who in 1715 became Member of Parliament for the City. They are all either originals or contemporary copies. They were tied up in a bundle marked ‘ Letters relating to the Rebellion of 1715,’ and they all fall within that year. The most important subject with which they deal is the Jacobite Rising, but they also give us many side- lights on Edinburgh affairs, national politics, and the personages of the time. The Letters have been transcribed by Miss Marguerite Wood, Keeper of the Burgh Records, who recognised their exceptional interest. Miss Wood has placed her transcript at the disposal of the Scottish History Society. The Letters are now printed by permission of the Magistrates and Council, who have also granted permission to reproduce as a frontispiece to the volume the portrait of Sir George Warrender which in 1930 was presented to the City by his descendant, Sir Victor Warrender, Bt., M.P. -

City As Lens: (Re)Imagining Youth in Glasgow and Hong Kong

Article YOUNG City as Lens: (Re)Imagining 25(3) 1–17 © 2017 SAGE Publications and Youth in Glasgow and YOUNG Editorial Group Hong Kong SAGE Publications sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/1103308816669642 http://you.sagepub.com Alistair Fraser1 Susan Batchelor1 Leona Li Ngai Ling2 Lisa Whittaker3 Abstract In recent years, a paradox has emerged in the study of youth. On the one hand, in the context of the processes of globalization, neoliberalism and precarity, the pat- terning of leisure and work for young people is becoming increasingly convergent across time and space. On the other hand, it is clear that young people’s habits and dispositions remain deeply tied to local places, with global processes filtered and refracted through specific cultural contexts. Against this backdrop, drawing on an Economic and Social Research Council/Research Grants Council (ESRC/RGC)- funded study of contemporary youth in Glasgow and Hong Kong, this article seeks to explore the role of the city as a mediating lens between global forces and local impacts. Utilizing both historical and contemporary data, the article argues that despite parallels in the impact of global forces on the structure of everyday life and work, young people’s leisure habits remain rooted in the fates and fortunes of their respective cities. Keywords Youth, globalization, space, social change, cities, comparative methods 1 SCCJR, Ivy Lodge, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland. 2 Department of Sociology/Centre for Criminology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. 3 University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland. Corresponding author: Alistair Fraser, SCCJR, Ivy Lodge, University of Glasgow, 63 Gibson Street, Glasgow G12 8LR, Scotland. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Digging up the Kirkyard: Death, Readership and Nation in the Writings of the Blackwood’s Group 1817-1839. Sarah Sharp PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 2 I certify that this thesis has been composed by me, that the work is entirely my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Sarah Sharp 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Penny Fielding for her continued support and encouragement throughout this project. I am also grateful for the advice of my secondary supervisor Bob Irvine. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation for this project. Special thanks are due to my parents, Andrew and Kirsty Sharp, and to my primary sanity–checkers Mohamad Jahanfar and Phoebe Linton. -

Chaucer's Presspak.Pub

Our History established 1964 1970’s label 1979: LAWRENCE BARGETTO in the vineyard The CHAUCER’S dessert wine story begins on the banks of Soquel “Her mouth was sweet as Mead or Creek, California. In 1964, winery president, Lawrence Bargetto, saw honey say a hand of apples lying an opportunity to create a new style of dessert wine made from fresh, in the hay” locally-grown fruit in Santa Cruz County. —THE MILLERS TALE With an abundant supply of local plums, Lawrence decided to make “They fetched him first the sweetest wine from the Santa Rosa Plums growing on the winery property. wine. Then Mead in mazers they combine” Using the winemaking skills he learned from his father, he picked the —TALE OF SIR TOPAZ fresh plums into 40 lb. lug boxes and dumped them into the empty W open-top redwood fermentation tanks. Since it was summer, the fer- The above passages were taken from mentation tanks were empty and could be used for this new dessert Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, wine experiment. a great literary achievement filled with rich images of Medieval life in Merry ole’ England. Immediately after the fermentation began, the cellars were filled with the delicate and sensuous aromas of the Santa Rosa Plum. Lawrence Throughout the rhyming tales one had not smelled this aroma in the cellars before and he was exhilarated finds Mead to be enjoyed by com- moner and royalty alike. with the possibilities. After finishing the fermentation, clarification, stabilization and sweet- ening, he bottled the wine in clear glass to highlight the alluring color of crimson. -

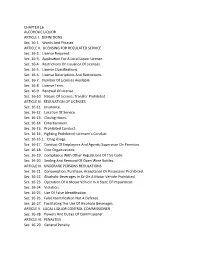

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. Words And Phrases. ARTICLE II. LICENSING FOR REGULATED SERVICE Sec. 16-2. License Required. Sec. 16-3. Application For A Local Liquor License. Sec. 16-4. Restrictions On Issuance Of Licenses. Sec. 16-5. License Classifications. Sec. 16-6. License Descriptions And Restrictions. Sec. 16-7. Number Of Licenses Available. Sec. 16-8. License Term. Sec. 16-9. Renewal Of License. Sec. 16-10. Nature Of License; Transfer Prohibited. ARTICLE III. REGULATION OF LICENSES Sec. 16-11. Insurance. Sec. 16-12. Location Of Service. Sec. 16-13. Closing Hours. Sec. 16-14. Entertainment. Sec. 16-15. Prohibited Conduct. Sec. 16-16. Fighting Prohibited; Licensee's Conduct. Sec. 16-16.1. Drug Usage. Sec. 16-17. Conduct Of Employees And Agents; Supervisor On Premises. Sec. 16-18. Civic Organizations. Sec. 16-19. Compliance With Other Regulations Of This Code. Sec. 16-20. Sealing And Removal Of Open Wine Bottles. ARTICLE IV. UNDERAGE PERSONS REGULATIONS Sec. 16-21. Consumption, Purchase, Acceptance Or Possession Prohibited. Sec. 16-22. Alcoholic Beverages In Or On A Motor Vehicle Prohibited. Sec. 16-23. Operation Of A Motor Vehicle In A State Of Impairment. Sec. 16-24. Violation. Sec. 16-25. Use Of False Identification. Sec. 16-26. False Identification Not A Defense. Sec. 16-27. Facilitating The Use Of Alcoholic Beverages. ARTICLE V. LOCAL LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSIONER Sec. 16-28. Powers And Duties Of Commissioner. ARTICLE VI. PENALTIES Sec. 16-29. General Penalty. ARTICLE I DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. WORDS AND PHRASES. Unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall be construed according to the definitions set forth below: ACTING IN THE COURSE OF BUSINESS. -

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History1

The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXV, 1: No. 219: April 2006, 1–27 MATTHEW H. HAMMOND Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish history1 ABSTRACT Historians have long tended to define medieval Scottish society in terms of interactions between ethnic groups. This approach was developed over the course of the long nineteenth century, a formative period for the study of medieval Scotland. At that time, many scholars based their analysis upon scientific principles, long since debunked, which held that medieval ‘peoples’ could only be understood in terms of ‘full ethnic packages’. This approach was combined with a positivist historical narrative that defined Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Normans as the harbingers of advances in Civilisation. While the prejudices of that era have largely faded away, the modern discipline still relies all too often on a dualistic ethnic framework. This is particularly evident in a structure of periodisation that draws a clear line between the ‘Celtic’ eleventh century and the ‘Norman’ twelfth. Furthermore, dualistic oppositions based on ethnicity continue, particu- larly in discussions of law, kingship, lordship and religion. Geoffrey Barrow’s Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, first published in 1965 and now available in the fourth edition, is proba- bly the most widely read book ever written by a professional historian on the Middle Ages in Scotland.2 In seeking to introduce the thirteenth century to such a broad audience, Barrow depicted Alexander III’s Scot- land as fundamentally -

South African Food-Based Dietary Guidelines

ISSN 1607-0658 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3)(Supplement):S1-S164 FBDG-SA 2013 www.sajcn.co.za Developed and sponsored by: Distribution of launch issue sponsored by ISSN 1607-0658 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3)(Supplement):S1-S164 FBDG-SA 2013 www.sajcn.co.za Table of contents Cited as: Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS. An 9. “Drink lots of clean, safe water”: a food-based introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines dietary guideline for South Africa Van Graan AE, Bopape M, Phooko D, for South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3):S1-S164 Bourne L, Wright HH ................................................................. S77 Guest Editorial 10. The importance of the quality or type of fat in the diet: a food-based dietary guideline for South Africa • Revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa: Smuts CM, Wolmarans P.......................................................... S87 challenges pertaining to their testing, implementation and evaluation 11. Sugar and health: a food-based dietary guideline Vorster HH .................................................................................... S3 for South Africa Temple NJ, Steyn NP .............................................................. S100 Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa 12. “Use salt and foods high in salt sparingly”: a food-based dietary guideline for South Africa 1. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary Wentzel-Viljoen E, Steyn K, Ketterer E, Charlton KE ............ S105 guidelines for South Africa Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS ........................................... S5 13. “If you drink alcohol, drink sensibly.” Is this 2. “Enjoy a variety of foods”: a food-based dietary guideline still appropriate? guideline for South Africa Jacobs L, Steyn NP................................................................ -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D.