Arxiv:2007.08994V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 21 Dec 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comprehensive Comparison Between APOGEE and LAMOST Radial Velocities and Atmospheric Stellar Parameters

A&A 620, A76 (2018) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833387 & c ESO 2018 Astrophysics Comprehensive comparison between APOGEE and LAMOST Radial velocities and atmospheric stellar parameters B. Anguiano1,2, S. R. Majewski1, C. Allende-Prieto3,4, S. Meszaros5,6, H. Jönsson7, D. A. García-Hernández3,4, R. L. Beaton8,9, ?, G. S. Stringfellow10, K. Cunha11,12, and V. V. Smith13 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4325, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, Macquarie University, Balaclava Rd, NSW 2109, Australia 3 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4 Universidad de La Laguna (ULL), Departamento de Astrofísica, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 5 ELTE Eötvös Lorand University, Gothárd Astrophysical Observatory, Szombathely, Hungary 6 Premium Postdoctoral Fellow of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary 7 Lund Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Theoretical Physics, Lund University, Box 43, 22100 Lund, Sweden 8 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, 4 Ivy Lane, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 9 The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA 10 Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, 389 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0389, USA 11 University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA 12 Observatório Nacional, São Cristóvõ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 13 National Optical Astronomy Observatories, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA Received 7 May 2018 / Accepted 18 July 2018 ABSTRACT Context. In the era of massive spectroscopy surveys, automated stellar parameter pipelines and their validation are extremely impor- tant for an efficient scientific exploitation of the spectra. -

New Mexico State University Department of Astronomy Las

505 New Mexico State University Department of Astronomy Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003 @S0002-7537~98!04901-4# This report covers events and activities that occurred during Karen Gloria, Tia Hoyes, Dan Long, and Russet McMillian. the calendar year 1997. Other observatory site staff are Norm Blythe, Project Aide; Jon Brinkmann, Scientific Instruments Engineer; Jon Davis, 1. PERSONNEL Telescope Systems Engineer; Bruce Gillespie, Site Manager; The faculty of the Astronomy Department includes Pro- Mark Klaene, Deputy Site Manager; Madonna Reyero, fessors Kurt S. Anderson, Reta F. Beebe, Bernard J. Mc- Records Technician; Gretchen Van Doren, Technical Writer; Namara, and William R. Webber; Associate Professor Rene´ John Wagoner, Carpenter; and Dave Woods, Electronics Walterbos ~Dept. Head!; Assistant Professors Jon A. Holtz- Technician. On-campus support staff include Dacia Pacheco man, Anatoly A. Klypin, and Mark S. Marley; College As- and Marilee Sage. Dr. Kurt Anderson is the observatory’s sistant Professors Nicholas Devereux, Chris Loken, Tom Site Director. Harrison, and Sarah Maddison; and Emeritus Professor Her- Instrument development and research activities of the bert A. Beebe. ARC facilities at Apache Point Observatory are detailed in a Adjunct members of the faculty include Jonathan Brink- separate Observatory Report. The 3.5 meter telescope has man ~Apache Point!, Roger E. Davis ~Science & Technology been fully operational for over three years, and used for a Corp.!, Richard B. Dunn ~NSO!, Nebojsa Duric ~UNM!,W. variety of imaging and spectroscopic investigations at optical Miller Goss ~NRAO!, Hunt Guitar ~Science & Technology and infrared wavelengths.It has seen daytime use for missile- Corp.!, Virginia Gulick ~NASA, ARC!, John J. -

Proposed Changes to Sacramento Peak Observatory Operations: Historic Properties Assessment of Effects

TECHNICAL REPORT Proposed Changes to Sacramento Peak Observatory Operations: Historic Properties Assessment of Effects Prepared for National Science Foundation October 2017 CH2M HILL, Inc. 6600 Peachtree Dunwoody Rd 400 Embassy Row, Suite 600 Atlanta, Georgia 30328 Contents Section Page Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Definition of Proposed Undertaking ................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Proposed Alternatives Background ................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Proposed Alternatives Description .................................................................................. 1-1 1.4 Area of Potential Effects .................................................................................................. 1-3 1.5 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.5.1 Determinations of Eligibility ............................................................................... 1-3 1.5.2 Finding of Effect .................................................................................................. 1-9 2 Identified Historic Properties ............................................................................................... -

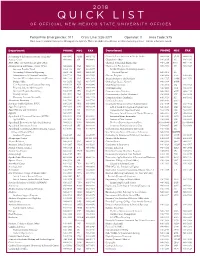

Quick List of Official New Mexico State University Offices

2018 QUICK LIST OF OFFICIAL NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY OFFICES Police/Fire Emergencies: 911 Crisis Line: 526-3371 Operator: 0 Area Code: 575 Data source: Human Resources Management System. This is an abbreviated list of official university offices. Unless otherwise noted. Department PHONE MSC FAX Department PHONE MSC FAX Accounting & Information Systems (Academic) 646-4901 3DH 646-1552 Center for Latin American & Border Studies 646-6814 3LAS 646-6819 Activity Center 646-2907 3M 646-4065 Chancellor’s Office 646-2035 3Z 646-6334 ADA Office (See Institutional Equity office) Chemical & Materials Engineering 646-1214 3805 646-7706 Administration and Finance, Senior VP for 646-2432 3AA 646-7855 Chemistry & Biochemistry 646-2505 3C 646-2649 Accounts Payable/ Travel 646-1189 3AP 646-1077 MARC Program (Maximizing Access to Accounting & Financial Reporting 646-1514 AFR 646-3900 Research Careers) 647-3476 3C Administration & Finance/Controller 646-7793 3AA 646-7855 Chicano Programs 646-4206 4188 646-1962 Associate VP for Administration and Finance 646-7793 3AA 646-7855 Special Assistant to the President 646-1727 3ORE 646-3574 Budget Office 646-2432 3AA 646-7855 Chihuahuan Desert Network 646-5294 3ARP Cost Accounting and Financial Reporting 646-1514 AFR 646-3900 Chile Pepper Institute 646-3028 3Q 646-6041 Financial Systems Administration 646-6727 3FSA 646-1994 Civil Engineering 646-3801 3CE 646-6049 Sponsored Projects Accounting 646-1675 SPA 646-1676 Communication Disorders 646-2402 3SPE 646-7712 Treasury Services 646-4019 3AA 646-1985 Communication -

Doing Astronomy with SDSS from Your Armchair Željko Ivezić, University of Washington & University of Zagreb “Partners in Learning” Webinar, Zagreb, 15

Doing astronomy with SDSS from your armchair Željko Ivezić, University of Washington & University of Zagreb “Partners in Learning” webinar, Zagreb, 15. XII 2010 Supported by: Microsoft Croatia and the Croatian National Science Foundation Apache Point Observatory, New Mexico Topics: • Sky Maps: from Hipparchos to digital sky surveys • The first large digital color map of the night sky: Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) • Astronomy from your armchair: How to use public SDSS databases? A peek into the future: LSST Context: modern observational methods in astronomy and astrophysics: • Large telescopes (~10m): faint objects, especially spectroscopy The Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea (Hawaii) Context: modern observational methods in astronomy and astrophysics: • Telescopes above the atmosphere: high angular resolution (e.g., the Hubble Space Telescope) and other wavelength regions (X-ray, radio, infrared) The HST in orbit and an example of a galaxy image Context: modern observational methods in astronomy and astrophysics: • Large telescopes (~10m): faint objects, especially spectroscopy • Telescopes above the atmosphere: high angular resolution (e.g., the Hubble Space Telescope) and other wavelength regions (X-ray, radio, infrared) • Large sky surveys: digital sensor tehnology (CCD: charge-coupled device), information tehnology (data processing and data distribution) Key point: modern sky surveys make all their data (images and catalogs) publicly available What is a sky map? Why are sky maps useful? • Sky map: – a list of all detected objects (stars, -

A Brief History of the Astrophysical Research Consortium and the Apache Point Observatory

Journal ofAstronomical Hisfotyand Heritage, 9(1), XX·XX (2006). A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ASTROPHYSICAL RESEARCH CONSORTIUM AND THE APACHE POINT OBSERVATORY J fm Peterson 8200 Fairway Dr. NE, Seattle, Washington 98115, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Glen Mackie Swinburne University of Technology, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This history of the Astrophysical Research Consortium (ARC) and the Apache Point Observatory (APO) describes why and how the ARC-was formed, !he vision for the APO, and the technology used to Implement that vision. In particular, It examines the building of a low cost, lightweight, f/1.75, 3.5 meter telescope with an experimental mirror cast al the Stewart Observatory Mirror Lab, and key .features of remote observing, rapid instrument change and flexible scheduling. The organizational challenge of unifying distinct Institutions and their astronomy programs, and the difficulty of gathering funds for this venture, are also explored. Key scientific results and achievements using the APO are noted. This paper Is based on Interviews with key personnel, documents in the ARC business files, and published papers and reports (Including astronomy department annual reports). Ke�words: history, astronomy, Apache Point Observatory, remote observing, spincast mirror 1 INTRODUCTION ually could fund or fully utilize it (Wallerstein, 2004), New Mexico State University, Princeton University, Like most human endeavor, astronomy depends on the University of Chicago, the University of Washing bigger and better tools to break through the frontiers of ton, and Washington State University formed the discovery and ensure the advancement of our know Astrophysical Research Consortium (ARC) in 1984 in ledge. -

Overview of the SDSS-IV Manga Survey: Mapping Nearby Galaxies at Apache Point Observatory Kevin Bundy University of Tokyo, Japan

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications Physics and Astronomy 12-10-2014 Overview of the SDSS-IV MaNGA Survey: Mapping Nearby Galaxies at Apache Point Observatory Kevin Bundy University of Tokyo, Japan Matthew A. Bershady University of Wisconsin - Madison David R. Law University of Toronto, Canada Renbin Yan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Niv Drory University of Texas - Austin See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Repository Citation Bundy, Kevin; Bershady, Matthew A.; Law, David R.; Yan, Renbin; Drory, Niv; MacDonald, Nicholas; Wake, David A.; Cherinka, Brian; Sánchez-Gallego, José R.; Weijmans, Anne-Marie; Thomas, Daniel; Tremonti, Christy; Masters, Karen; Coccato, Lodovico; Diamond-Stanic, Aleksandar M.; Aragón-Salamanca, Alfonso; Avila-Reese, Vladimir; Badenes, Carles; Falcón-Barroso, Jésus; Belfiore, Francesco; Bizyaev, Dmitry; Blanc, Guillermo A.; Bland-Hawthorn, Joss; Blanton, Michael R.; Brownstein, Joel R.; Byler, Nell; Cappellari, Michele; Conroy, Charlie; Dutton, Aaron A.; Emsellem, Eric; and Zhang, Kai, "Overview of the SDSS-IV MaNGA Survey: Mapping Nearby Galaxies at Apache Point Observatory" (2014). Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications. 332. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub/332 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics and Astronomy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Quick Facts 2008-2009 Founded in 1888, We Are New Mexico’S Land-Grant Institution, Dedicated to Teaching, Research and Extension Service

Quick Facts 2008-2009 Founded in 1888, we are New Mexico’s land-grant institution, dedicated to teaching, research and extension service. By providing educational opportunities through our statewide presence we offer students a multitude of possibilities for learning and self-discovery. A true reflection of the region’s vibrant mix of ethnic and cultural communities, we are the best place to live, learn and thrive.TM • Groundbreaking research in biosciences, natural resources, aerospace, information sciences and U.S.-Mexico border development • Accredited by the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools • Rated among the nation’s top 30 universities for Hispanic and Native American students by Diverse: Issues in Higher Education • Designated a NASA Space Grant College • Students from 50 states and 85 foreign countries • The only university in New Mexico that offers an Honors College; aerospace, industrial and surveying engineering programs; and a PGA Golf ManagementTM program • In a 10-year span, NMSU faculty claimed half of the New Mexico Professor of the Year honors awarded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Council for Advancement and Support of Education • NMSU’s Cooperative Extension Service and Agricultural Experiment Station have been cited as exceeding expectations in research and public service by the NM Commission on Higher Education • NMSU ranks in the top 110 institutions in the country in terms of federal research expenditures DEGREE PROGRAMS: 60 certificate, 57 associate, 81 bachelor’s, 50 master’s, 20 doctoral and 2 specialist in education. COLLEGES: Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences; Arts and Sciences; Business; Education; Engineering; Extended Learning; Health and Social Services; Honors. -

Internet Services for Professional Astronomy - H

Internet Services for Professional Astronomy - H. Andernach Published in "Internet Resources for Professional Astronomy", eds. M.R. Kidger, I. Pérez-Fournon & F. Sánchez, Cambridge University Press, 1999. INTERNET SERVICES FOR PROFESSIONAL ASTRONOMY Heinz Andernach Depto. de Astronomía, IFUG, Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, C.P. 36000, Mexico Email: [email protected] Abstract. A (subjective) overview of Internet resources relevant to professional astronomers is given. Special emphasis is put on databases of astronomical objects and servers providing general information, e.g. on astronomical catalogues, finding charts from sky surveys, bibliographies, directories, browsers through multi-wavelength observational archives, etc. Archives of specific observational data will be discussed in more detail in other chapters of this book, dealing with the corresponding part of the electromagnetic spectrum. About 200 different links are mentioned, and every attempt was made to make this report as up-to-date as possible. As the field is rapidly growing with improved network technology, it will be just a snapshot of the present situation. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION DATA CENTRES ASTRONOMICAL CATALOGUES RETRIEVING INFORMATION ON OBJECTS Object Databases Pseudo-Databases: Searchable Collections of Catalogues Archives of Observational Data DIGITAL OPTICAL SKY SURVEYS, FINDING CHARTS, & PLATE CATALOGUES Digitized Sky Survey Images file:///E|/moe/HTML/Andernach/Ander_contents.html (1 of 2) [11/04/2003 4:07:49 PM] Internet Services for Professional Astronomy - H. Andernach Object Catalogues and Finding Charts from DSS Catalogues of Direct Plates An Orientation Tool for the Galactic Plane Future Surveys BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERVICES Abstract and Article Servers Preprint Servers Preprint Lists from NRAO and STScI Electronic Journals Tables of Contents ``Grey Literature'': Newsletters, Observatory Publications, etc. -

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev (2012) 167:93–140 DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 / Published online: 18 March 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

For the Las Cruces Bulletin's Best

GET SOLAR & AC AND SAVE BIG SAVE YOUR ELECTRIC BILL EACH MONTH 25 YEAR WARRANTY $89.94 Local news and entertainment since 1969 September 18 - 24, 2020 COMBINED A MONTH Amana Lifetime Warranty Last AC You’ll Ever Kim Cattrall Buy gets ‘Filthy Lic #380200 • 4.38 kw • $36,000 financed at 2.99% is Rich’ as combo price $89.94 for 18 months then re-amortize OAC. Fox series 575-449-3277 YELLOWBIRDAC.COM • YELLOWBIRDSOLAR.COM premieres 2 x 5.5” ad PHARMACY Kim Cattrall stars PROUDLY SERVING LAS CRUCES in “Filthy Rich,” AFTER CARING FOR NEW MEXICANS premiering Monday FOR MORE THAN 60 YEARS! on Fox. RX Innovations is a local, comprehensive pharmacy for all types of facilities. • Long-term care • Assisted Living • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing • Hospice and more Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of RX Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad HEALTHY Entertainment Guide HORIZONS Inside FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2020 I Volume 52, Number 38 I lascrucesbulletin.com COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER INSIDE NEWS Remembering Full moon activity 9/11/2001 on the horizon page 12 NEWS Minimum wage discussion gets heated page 19 A&E James Ethington puts out an album page 26 A&E BULLETIN PHOTO BY MIKE COOK Eye-popping art Members of the Las Cruces Fire Department Honor Guard conducted a special ceremony Friday morning, Sept. 11, at city Fire Station #1, 201 E. Picacho Ave. -

NMSU Department of Astronomy Department Handbook 2020-2021

NMSU Department of Astronomy Department Handbook 2020-2021 1 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the NMSU Department of Astronomy. We strive to provide a vigorous, exciting program of research and education in Astronomy and Astrophysics, covering a broad range of interests, from planetary science and extra-solar planets, to cosmology. With the ARC 3.5-m and NMSU 1-m telescopes at the Apache Point Observatory, as well as the Sloan 2.5 meter telescope at APO and our 24" at Tortugas Mountain, we offer exciting opportunities for observational projects. These telescopes combined with the Sunspot Solar Observatory at Sacramento Peak, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory near Socorro, NM, the Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories, Kirtland Air Force Base, all of the national facilities, as well as the in-house NASA Planetary Data System Atmospheres data archive Node, offer excellent opportunities for research on the MS and Ph.D. levels. This guide is intended to help you through the procedures required by NMSU to achieve an advanced degree in Astronomy. You should read it carefully and then feel free to ask your faculty advisor any questions that arise. This document is constantly evolving, so any comments that you have to improve it would be appreciated. The policies and procedures outlined in this guide will be effective for the 2020-2021 entering class. More senior students may choose to follow these guidelines or those given to them upon entrance into the program. Please note that it is impossible for any written guide to anticipate all questions that students may have about the program, and that the program itself is an evolving entity.