Assault on the Roman Rite by John W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Origins of the Roman Liturgy - Mass

1 Origins of the Roman Liturgy - Mass Through the centuries the Mass of the Roman Rite has come to be divided into 4 major sections. These are: The Introductory Rites - the congregation is called to prayer. The Liturgy of the Word - also known as the Mass of the Catechumens in the patristic & early Medieval period. The Liturgy of the Eucharist - known as the Mass of the Faithful in the patristic & early Medieval period. The Concluding Rites - the congregation is sent forth to proclaim the Word & put it into practice in addition to the lessons learned in the liturgy. How it all began - NT Origins of the Roman Liturgy It began on the same Thursday night on which Jesus was betrayed. Jesus came with his closest disciples to the upper room in Jerusalem where he had instructed two of them to prepare the Passover meal. Judas, one of the Twelve chosen Apostles, had already privately agreed to lead the authorities to where Jesus would be praying in a garden in secret after the meal, knowing there would be no one but these few closest disciples around him to defend him. During the Passover meal, Jesus as the central figure took some bread & blessed it & broke it ready to hand around. That was customary enough. But then he said, for all to hear: “take, eat; this is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me” (Mt 26:26; Mk 14:22; Lk 22:19). This was something totally new. Another memory of the occasion, related by Paul but as old in origin as the first, has Jesus say: “This is my body which is broken for you. -

Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite At

Mass in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite A Solemn High Mass celebrated in the Extraordinary Form of the Mass of the Roman Rite (according to the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal) is scheduled for Sacred Heart Cathedral on Sunday, September 15, 2019, 3:00 pm. Fr. Daniel Geddes from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, Pastor of Holy Family Parish in Vancouver, will be the celebrant. As a simple explanation, in 2007 Pope Benedict XVI issued a document entitled “Summorum Pontificum” which gave priests anywhere around the world permission to celebrate the Mass using the 1962 Missal. In his letter to bishops concerning the document, he explained that the liturgical tradition of the Roman Rite incorporated two forms – the ordinary, which we celebrate regularly, and the extraordinary, to which many have continued to be devoted. Both forms belong to the Roman Rite and are to be seen as the continual flow of the 2000-year liturgical tradition of the Church. The pope emphasized there was no fracture of the tradition at the Second Vatican Council. Both forms are celebrated in Latin, although the current edition of the Roman Missal allows for vernacular languages to be used. The Apostolic Letter, Summorom Pontificum was issued on July 7, 2007 and carried an effective date of September 14, 2007. Hence, 12 years after the letter’s effective date, Mass will again be offered at Sacred Heart Cathedral in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite. Members of the UnaVoce Prince George Chapter will be providing servers and a schola (choir). -

The Development of the Roman Rite by Michael Davies

The Development of the Roman Rite By Michael Davies The Universe is the Catholic newspaper with the largest circulation in Britain. On 18 May 1979 its principal feature article was by one Hugh Lindsay, Bishop of Hexam and Newcastle. The Bishop's article was entitled "What Can the Church Change?" It was a petulant, petty, and singularly ill-informed attack upon Archbishop Lefebvre and Catholic traditionalists in general. It is not hard to understand why the Archbishop is far from popular with the English hierarchy, and with most hierarchies in the world for that matter. The Archbishop is behaving as a true shepherd, defending the flock from who would destroy it. He is a living reproach to the thousands of bishops who have behaved as hirelings since Vatican II. They not only allow enemies to enter the sheepfold but enjoy nothing more than a "meaningful dialogue" with them. The English Bishops are typical of hierarchies throughout the world. They allow catechetical programs in their schools which leave Catholic children ignorant of the basis of their faith or even teach a distorted version of that faith. When parents complain the Bishops spring to the defense of the heterodox catechists responsible for undermining the faith of the children. The English Bishops remain indifferent to liturgical abuse providing that it is initiated by Liberals. Pope Paul VI appealed to hierarchies throughout the world to uphold the practice of Communion on the tongue. Liberal clerics in England defied the Holy See and the reaction of the Bishops was to legalize the practice. The same process is now taking place with the practice of distributing Communion under both kinds at Sunday Masses. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Eastern Rite Catholicism

Eastern Rite Catholicism Religious Practices Religious Items Requirements for Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals Sacred Writings Organizational Structure History Theology RELIGIOUS PRACTICES Required Daily Observances. None. However, daily personal prayer is highly recommended. Required Weekly Observances. Participation in the Divine Liturgy (Mass) is required. If the Divine Liturgy is not available, participation in the Latin Rite Mass fulfills the requirement. Required Occasional Observances. The Eastern Rites follow a liturgical calendar, as does the Latin Rite. However, there are significant differences. The Eastern Rites still follow the Julian Calendar, which now has a difference of about 13 days – thus, major feasts fall about 13 days after they do in the West. This could be a point of contention for Eastern Rite inmates practicing Western Rite liturgies. Sensitivity should be maintained by possibly incorporating special prayer on Eastern Rite Holy days into the Mass. Each liturgical season has a focus; i.e., Christmas (Incarnation), Lent (Human Mortality), Easter (Salvation). Be mindful that some very important seasons do not match Western practices; i.e., Christmas and Holy Week. Holy Days. There are about 28 holy days in the Eastern Rites. However, only some require attendance at the Divine Liturgy. In the Byzantine Rite, those requiring attendance are: Epiphany, Ascension, St. Peter and Paul, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Christmas. Of the other 15 solemn and seven simple holy days, attendance is not mandatory but recommended. (1 of 5) In the Ukrainian Rites, the following are obligatory feasts: Circumcision, Easter, Dormition of Mary, Epiphany, Ascension, Immaculate Conception, Annunciation, Pentecost, and Christmas. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

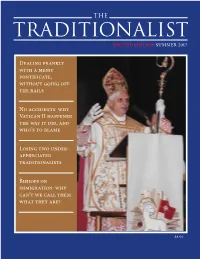

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

The Attractiveness of the Tridentine Mass by Alfons Cardinal Stickler

The Attractiveness of the Tridentine Mass by Alfons Cardinal Stickler Cardinal Alfons Stickler, retired prefect of the Vatican Archives and Library, is normally reticent. Not so during his trip to the New York area in May [1995]. Speaking at a conference co-sponsored by Fr. John Perricon's ChistiFideles and Howard Walsh's Keep the Faith, the Cardinal scored Catholics within the fold who have undermined the Church—and in the final third of his speech made clear his view that the "Mass of the post-Conciliar liturgical commission" was a betrayal of the Council fathers. The robust 84-year-old Austrian scholar, a Salesian who served as peritus to four Vatican II commissions (including Liturgy), will celebrate his 60th anniversary as a priest in 1997. Among his many achievements: The Case for Clerical Celibacy (Ignatius Press), which documents that the celibate priesthood was mandated from the earliest days of the Church. Cardinal Stickler lives at the Vatican. The Tridentine Mass means the rite of the Mass which was fixed by Pope Pius V at the request of the Council of Trent and promulgated on December 5, 1570. This Missal contains the old Roman rite, from which various additions and alterations were removed. When it was promulgated, other rites were retained that had existed for at least 200 years. Therefore, is more correct to call this Missal the liturgy of Pope Pius V. Faith and Liturgy From the very beginning of the Church, faith and liturgy have been intimately connected. A clear proof of this can be found in the Council of Trent itself. -

Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport

DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport These pages may be reproduced by parish and Diocesan staff for their use Policy promulgated at the Pastoral Center of the Diocese of Davenport–effective September 14, 2007 Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross Revised November 27, 2011 Revised October 15, 2012 Most Reverend Martin Amos Bishop of Davenport TABLE OF CONTENTS §IV-249 POLICIES FOR IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT: INTRODUCTION 1 §IV-249.1 THE ROLE OF THE BISHOP 2 §IV-249.2 FACULTIES 3 §IV-249.3 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF MASS 4 §IV-249.4 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE OTHER SACRAMENTS AND RITES 6 §IV-249.5 REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 6 APPENDICES Appendix A: Documentation Form 7 Appendix B: Resources 8 0 §IV-249 Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport §IV-249 POLICIES IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Introduction In the 1980s, Pope John Paul II established a way to allow priests with special permission to celebrate Mass and the other sacraments using the rites that were in use before Vatican II (the 1962 Missal, also called the Missal of John XXIII or the Tridentine Mass). Effective September 14, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI loosened the restrictions on the use of the 1962 Missal, such that the special permission of the bishop is no longer required. This action was taken because, as universal shepherd, His Holiness has a heart for the unity of the Church, and sees the option of allowing a more generous use of the Mass of 1962 as a way to foster that unity and heal any breaches that may have occurred after Vatican II. -

Patristic Teaching on the Priesthood of the Faithful

PATRISTIC TEACHING ON THE PRIESTHOOD OF THE FAITHFUL The priesthood of the faithful is a question which has received a new emphasis in recent decades. It is well known that because of the Catholic reaction to the errors of the Reformers the idea of a priesthood of the faithful was pushed into the background for centuries. The reawakened interest in this question manifests itself in various ways. Firstly, the doctrine has been taught by the Church’s teaching authority. It is true that the magisterium has not issued any definitive pronouncement on the many problems which arise in connection with this doctrine. However, the teaching authority of the Church has taught that the faithful have a share in the priest- hood of Christ and it has condemned a theory which confuses this priesthood of all Christians with the priesthood of Holy Orders.’ Theologians, too, have been drawing this doctrine from the obscurity in which it has been shrouded for so long. It is true that they have not as yet arrived at a completely stabilized theology on the matter. Nevertheless, it is easy to trace a steady evolution in the teaching of theologians on the matter throughout the last thirty years - an evolution from an attitude of cautiousness to a general acceptance of the priesthood of the faithful as a reality, as something which cannot be defined in terms of the priesthood of Holy Orders but which is analogous to it, and as something which is exercised by offering the sacrifice of a holy life and by participating in the offering of the Mass.2 The present article aims at discovering to what extent the Fathers of the Church had developed a doctrine of a priesthood of all Christians, what was their teaching on the nature, origin and function of that priesthood. -

SHORT HISTORY of the ROMAN MASS by Michael Davies

SHORT HISTORY OF THE ROMAN MASS by Michael Davies Table of Contents: Gradual Development of Ceremonies The End of Persecutions The Gallican Rite The Origins of the Roman Rite and its Liturgical Books The Canon of the Mass Dates from the 4th Century The Reform of St. Gregory the Great Eastern and Gallican Additions to the Roman Rite A Sacred Heritage Since the 6th Century The Reform of Pope St. Pius V Not a New Mass Revisions after 1570 Our Ancient Liturgical Heritage GRADUAL DEVELOPMENT OF CEREMONIES Although there was considerable liturgical uniformity in the first two centuries there was not absolute uniformity. Liturgical books were certainly being used by the middle of the 4th century, and possibly before the end of the third, but the earliest surviving texts date from the seventh century, and musical notation was not used in the west until the ninth century when the melodies of Gregorian chant were codified. The only book known with certainty to have been used until the fourth century was the Bible from which the lessons were read. Psalms and the Lord's Prayer were known by heart, otherwise the prayers were extempore. There was little that could be described as ceremonial in the sense that we use the term today. Things were done as they were done for some practical purpose. The lessons were read in a loud voice from a convenient place where they could be heard, and bread and wine were brought to the altar at the appropriate moment. Everything would evidently have been done with the greatest possible reverence, and gradually and naturally signs of respect emerged, and became established customs, in other words liturgical actions became ritualized. -

St. Ambrose and the Architecture of the Churches of Northern Italy : Ecclesiastical Architecture As a Function of Liturgy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2008 St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy. Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider 1948- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Schneider, Sylvia Crenshaw 1948-, "St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1275 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B.A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2008 Copyright 2008 by Sylvia A. Schneider All rights reserved ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B. A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Approved on November 22, 2008 By the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________ Dr. -

Producing and Contesting Martyrdom in Pre-Decian Roman North Africa

Producing and Contesting Martyrdom in Pre-Decian Roman North Africa Carly Daniel-Hughes Introduction In his defense of the Christian faith, the Apology, the Christian writer Tertullian of Carthage mocks that, while imperial officials slaughter Christians, when they spill their blood they merely swell the ranks of the faithful. “The blood of the martyrs is seed,” he retorts.1 Yet the power that Tertullian gives the mar- tyrs was not the obvious outcome of Roman violence against Christ-followers. Many people in the Roman world incurred corporeal violence at the hands of the Roman juridical system (imprisonment, torture, and in some cases, death), yet few subjected to these punishments were memorialized as martyrs. It was in the recording, retelling, and remembering of their deaths—in the attribution of cosmic and theological significance to them—that the martyrs were produced and given their dominant place in the Christian imagination.2 Tertullian (ca. 160–220 ce) was integral to this discursive effort. Along with others, such as Origen and Irenaeus, he constructed and theorized “martyr- dom,” and then promoted it to his community.3 Those who died for their religious allegiance (or who were willing to do so), these theorists held, were imitators of Christ’s passion.4 They interpreted the martyrs’ deaths in sacrificial terms and drew on biblical images and language to do so.5 Their visions of mar- 1. Apol. 50.13. 2. Castelli, Martyrdom and Memory, 173; also Matthews, Perfect Martyr, 4. 3. I borrow terminology of theorizing from Castelli, Martyrdom and Memory, 33–68. 4. Early Christians had various understandings of what this imitation entailed, reflect- ing their differing christologies; see esp.