The Early Days II – CAT Operations in China 1949-50 by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Thoughts on the Civil Aviation Law of the People's Republic of China Wu Jianduan

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 62 | Issue 3 Article 11 1997 A Milestone of Air Legislation in China - Some Thoughts on the Civil Aviation Law of the People's Republic of China Wu Jianduan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Wu Jianduan, A Milestone of Air Legislation in China - Some Thoughts on the Civil Aviation Law of the People's Republic of China, 62 J. Air L. & Com. 823 (1997) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol62/iss3/11 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. A MILESTONE OF AIR LEGISLATION IN CHINA-SOME THOUGHTS ON THE CIVIL AVIATION LAW OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Wu JIANDUAN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 823 II. THE LEGISLATIVE SYSTEM IN CHINA .......... 824 III. NATIONALITY AND REGISTRATION ............ 828 IV. RIGHTS IN AIRCRAFT ............................ 830 V. LEASE OF CIVIL AIRCRAFT ...................... 832 VI. AIR SAFETY ADMINISTRATION .................. 832 A. THE ADMINISTRATION OF AIRWORTHINESS ....... 832 B. SAFETY AND SECURITY OF CML AIRPORTS ....... 833 C. RESPONSIBILITIES OF PUBLIC AIR TRANSPORT ENTERPRISES .................................... 833 D. GENERAL SAFEy CONCERNS ..................... 834 VII. PUBLIC AIR TRANSPORT ENTERPRISE ......... 835 VIII. CARRIER'S LIABILITY ............................ 836 IX. CONCLUDING REMARKS ........................ 839 I. INTRODUCTION 0N OCTOBER 30, 1995, the Civil Aviation Law of the Peo- ple's Republic of China ("Civil Aviation Law" or "Law") was adopted at the Sixteenth Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People's Congress. -

Guide to the MS:202 James W. Davis Letters

________________________________________________________________________ Guide to the MS:202 James W. Davis Letters Karen D. Drickamer December, 2016 MS – 202: James W. Davis Letters (1 box, .33 cu. Ft.) Inclusive Dates: 1951 - 1968 Bulk Dates: 1966-1968 Processed by: Karen D. Drickamer, December 2016 Provenance: Purchased from Michael Brown Rare Books Biographical Note: James Walter Davis was born in 1910, enlisted in the Army in 1930, completed his Basic training at Greenwood, Mississippi, and was assigned to Army Field Artillery. He really wanted Air Corps so he went to night school. He was eventually received into Cadet Training for the Army Air Corps at Mitchell Field, Long Island, New York, and graduated from Craig Field, Selma, Alabama. He became a flight instructor and instrument instructor piloting B24s and C-54s. By 1942, the Army had created Air Transport Command (ATC), which was the first service able to deliver supplies and equipment to combat theaters around the world by air. At its height in August 1945, ATC operated more than 3200 transport aircraft and employed 209,000 personnel. James Davis flew for ATC in Europe, Egypt, India, China, and Brazil. He resigned as a major in 1946 to return home to help his ailing mother. Shortly after her death, James re- enlisted in the Army Air Force as a Sergeant Major. He married Janet Wilcox in 1947. By the time of the Berlin Air Lift (1948-49), James was once again a commissioned officer with the rank of major. He served in Germany for 3 years, stationed at Furstenfeldbruck AFB (“Fursty”) near Munich. Davis returned to the States on detached service, flying for Capital Airways, (a primary civilian carrier for the military's Logistic Air Support (LOGAIR) program) flying cargo for the CIA. -

AIR AMERICA: DOUGLAS C-54S by Dr

AIR AMERICA: DOUGLAS C-54s by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 15 August 2003, last updated on 15 March 2021 An Air America C-54 at Tachikawa in 1968 (Air America Log, vol. II, no. 5, 1968, p.5) The types of missions flown by Air America’s C-54s: From the times of Civil Air Transport, Air America had inherited 3 C-54s or DC-4s: Two of them were assigned to the Booklift contract to transport the Stars and Stripes from Japan to Korea and one of them seems to have been used by Civil Air Transport or other carriers like Air Vietnam (on lease) or VIAT or Vietnamese Air Transport,1 that is Bureau 45B – Northern Service (Biet Kích So Bac; see: http://ngothelinh.tripod.com/Tribute.htm), the front used by the CIA and the South Vietnamese Government for commando raids into North Vietnam between 1961 and 1964. In 1965 two of Air America’s C-54s were converted to FAA standards and given US registry as had been requested for service under the new Booklift contract. At the same time two more C-54s were acquired for use out of Taipei under a new contract with the USAF’s Logistical Support Group. Another C-54 (B-1016) was acquired in late 66 for use as a cargo aircraft first by Civil Air Transport and later by Air America who used it to carry Company properties between the main airports, as needed. And this role allowed it to become the last C-54 to remain with Air America. -

Research Studies Series a History of the Civil Reserve

RESEARCH STUDIES SERIES A HISTORY OF THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By Theodore Joseph Crackel Air Force History & Museums Program Washington, D.C., 1998 ii PREFACE This is the second in a series of research studies—historical works that were not published for various reasons. Yet, the material contained therein was deemed to be of enduring value to Air Force members and scholars. These works were minimally edited and printed in a limited edition to reach a small audience that may find them useful. We invite readers to provide feedback to the Air Force History and Museums Program. Dr. Theodore Joseph Crackel, completed this history in 1993, under contract to the Military Airlift Command History Office. Contract management was under the purview of the Center for Air Force History (now the Air Force History Support Office). MAC historian Dr. John Leland researched and wrote Chapter IX, "CRAF in Operation Desert Shield." Rooted in the late 1930s, the CRAF story revolved about two points: the military requirements and the economics of civil air transportation. Subsequently, the CRAF concept crept along for more than fifty years with little to show for the effort, except for a series of agreements and planning documents. The tortured route of defining and redefining of the concept forms the nucleus of the this history. Unremarkable as it appears, the process of coordination with other governmental agencies, the Congress, aviation organizations, and individual airlines was both necessary and unavoidable; there are lessons to be learned from this experience. Although this story appears terribly short on action, it is worth studying to understand how, when, and why the concept failed and finally succeeded. -

170818 華航 Csr報告書 英文 01 封面

Flying a Course towards Sustainability China Airlines Corporate Sustainability Report 2016 Contents Preface About This Report 02 A Letter from Our Management 04 0 About China Airlines 06 Overview of CAL’s Sustainable 1-1 CAL Vision of Sustainable Development 10 Development Strategies 1-2 Mode of Creation for CAL Sustainable Development 13 1 1-3 Sustainable Development Strategies 15 Main Frame of Sustainable 2-1 Stakeholder Engagement and Materiality Analysis 28 Development 2-2 Trust 35 2 2-3 Human Resources 46 2-4 Cooperation 77 2-5 Environment 84 2-6 Society 106 Foundations for 3-1 Sustainability Governance 118 3 Sustainability Development 3-2 Corporate Governance 122 Appendix Disclosure of Management Approach on Material Aspects for CAL 134 GRI G4 Index 138 Independent Assurance Reports 146 Preface 0-1 About This Report 0-2 A Letter from Our Management 0-3 About China Airlines 0 Cover Story Square 0-10-1 The sustainable door of China Airlines, inviting the readers to open AbouAboutt this report (including China Airlines' prole, external armation, and ThiThiss ReportReport history). Circle The sustainable management core of China Airlines (including the sustainable vision, mission, and the model for creating sustainable value). Number of entities The results of engaging with stakeholders through the sustainable strategies (including 7 types of stakeholders and 5 sustainable The ve overlapping ovals on the cover represent the ve petals of the plum blos- strategies). som—the symbol of China Airlines—which in turn represent the ve following frame- Arc works of China Airlines: the history, management core, sustainable strategy, operation The arc formed by stacked corner- principles, and stakeholder engagement. -

Clandestine US Operations: Indonesia 1958, Operation "Haik"

Clandestine US Operations: Indonesia 1958, Operation "Haik" (Feb 10, 2008 at 07:06 PM) - Contributed by Tom Cooper (introduction) & Marc Koelich (chronology & notes) - Last Updated () Short overview of air combats caused by the US clandestine operations against Indonesia, in late 1950s. Basically, there were three kinds of US clandestine and covert operations: - CIA operations, which were essentially para-military in nature, and usually used some kind of a front (about which usually not really much is known until today); - covert USAF operations, flown by aircraft with or without US- markings (meanwhile most of such operations were well covered in different publications) - private enterprises, most of which worked on a smuggling for profit efforts (the history of most such operations remains to be published). Their relatively small volume characterized usual para-military operations organized by the CIA, with a small number of aircraft involved (except in SEA), and by their air-to-ground tasks. Types used foremost during the 1950s and 1960s were Douglas B-26 Invader and North American P-51 Mustang, which were available in abundance after the end of the WWII, and large number of which were now in storage, from where they could be removed without much attention from the public. If any kind of aerial opposition was expected, everything possible - sometimes short of engaging official US military forces - was tried in order to neutralize it early during the operation by a concentrated counter-air operation. Despite this, several times US aircraft involved in clandestine operations were engaged in air-to-air combats by local air forces, and here are the backgrounds behind such cases. -

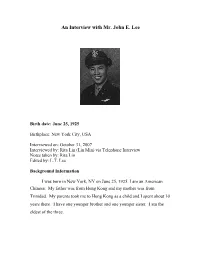

An Interview with Mr. John E. Lee

An Interview with Mr. John E. Lee Birth date: June 25, 1925 Birthplace: New York City, USA Interviewed on: October 31, 2007 Interviewed by: Rita Lin (Lin Min) via Telephone Interview Notes taken by: Rita Lin Edited by: L.T. Lee Background Information I was born in New York, NY on June 25, 1925. I am an American Chinese. My father was from Hong Kong and my mother was from Trinidad. My parents took me to Hong Kong as a child and I spent about 10 years there. I have one younger brother and one younger sister. I am the eldest of the three. John E. Lee P2 My flying career started soon after graduation from high school and the equivalent of two years college. I enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corp as an aviation cadet in January 1944. I graduated with the class of 45-E on August 4, 1945 at Douglas Army Air Base, Arizona. I was commissioned as a lieutenant and remained at Douglas AAB, AZ. During that time WWII was ending and I was transferred to the Training Command as a flight instructor on the Billy Mitchell B-25’s to train Chinese Air Force Cadets, West Point cadets and foreign student pilots under the lend-lease program. This position ended in November 1946. Working with Central Air Transport Corporation (CATC) in Shanghai At the end of 1946, I was discharged from the US Air Force and I went to Shanghai, China to join a Chinese airline company, Central Air Transport Corporation (CATC). At first the Chinese Civil Aviation Administration (CCAA) rejected my application for an Airline Transport rating because I was under age. -

Asean Single Aviation Market and Indonesia - Can It Keep up with the Giants?

Indonesia Law Review (2014) 2 : 163-175 ISSN: 2088-8430 | e-ISSN: 2356-2129 ~ 163 ~ ASEAN SINGLE AVIATION MARKET AND INDONESIA - CAN IT KEEP UP WITH THE GIANTS? Ruwantissa Abeyratne* * The author is President and CEO of Global Aviation Consultancies Inc, Montreal and former Senior Legal Officer, International Civil Aviation Organization. Article Info Received : 3 August 2014 | Received in revised form : 10 September 2014 | Accepted : 1 October 2014 Corresponding author’s e-mail : [email protected] [email protected]. Abstract Indonesia’s demand for air transport is higher in proportion to its GDP per capita. Its economy can be expected to grow 6% to 10% annually. A single aviation market could add another 6% to 10% growth in sheer demand. Yet its airports are badly in need of expansion, its infrastructure is bursting at its seems, and above all, its airlines are strongly resisting liberalization of air transport in the region for fear of being wiped out by stronger contenders in the region. Against this backdrop, it is incontrovertible that Indonesia’s civil aviation is intrinsically linked to regional and global considerations. A single aviation market in the ASEAN region will bring both benefits to Indonesia and challengers to its air transport sector. This article discusses the economic and regulatory challenges that Indonesia faces with the coming into effect of the ASEAN Single Aviation market in 2015. Keywords: ASEAN, Single Aviation Market, Regional Law. Abstract Permintaan transportasi udara di Indonesia lebih tinggi sebanding dengan PDB per kapita. Ekonominya dapat diperkirakan akan tumbuh 6 % sampai 10 % per tahun. Sebuah pasar penerbangan tunggal bisa menambah 6 % sampai 10 % pertumbuhan permintaan. -

AIR AMERICA - COOPERATION with OTHER AIRLINES by Dr

AIR AMERICA - COOPERATION WITH OTHER AIRLINES by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 23 August 2010, last updated on 24 August 2015 1) Within the family: The Pacific Corporation and its parts In a file called “Air America - cooperation with other airlines”, one might first think of Civil Air Transport Co Ltd or Air Asia Co Ltd. These were not really other airlines, however, but part of the family that had been created in 1955, when the old CAT Inc. had received a new corporate structure. On 28 February 55, CAT Inc transferred the Chinese airline services to Civil Air Transport Company Limited (CATCL), which had been formed on 20 January 55, and on 1 March 55, CAT Inc officially transferred the ownership of all but 3 of the Chinese registered aircraft to Asiatic Aeronautical Company Limited, selling them to Asiatic Aeronautical (AACL) for one US Dollar per aircraft.1 The 3 aircraft not transferred to AACL were to be owned by and registered to CATCL – one of the conditions under which the Government of the Republic of China had approved the two-company structure.2 So, from March 1955 onwards, we have 2 official owners of the fleet: Most aircraft were officially owned by Asiatic Aeronautical Co Ltd, which changed its name to Air Asia Co Ltd on 1 April 59, but three aircraft – mostly 3 C-46s – were always owned by Civil Air Transport Co Ltd. US registered aircraft of the family like C-54 N2168 were officially owned by the holding company – the Airdale Corporation, which changed its name to The Pacific Corporation on 7 October 57 – or by CAT Inc., which changed its name to Air America on 3 31 March 59, as the organizational chart of the Pacific Corporation given below shows. -

An Incident in the Prri/Permesta Rebellion of 1958

AN INCIDENT IN THE PRRI/PERMESTA REBELLION OF 1958 Daniel F. Doeppers In February 1958 certain elements of the Indonesian Army partici pated in a revolt against the government of President Sukarno. This action was centered in the outer islands of Sumatra and Sulawesi (Celebes), and although the major cities had fallen to the government by June 1958, the rebellion sputtered on until 1961. The revolt failed in the face of unexpectedly resolute action by the Indonesian government. At that time there were charges that the United States participated in this conflict in a limited and clandestine fashion-- on the side of the rebels.1 Except for the occasional rebel use of British or American military airfields, Western intervention has been difficult to trace to official agencies. This article presents evi dence that a U.S. Navy reconnaissance plane, flown by a regularly assigned active duty crew, was very nearly shot down during a clas sified mission in the Sulawesi area on March 27, 1958. The Incident and the Evidence While searching for historical information on urban squatting in the Philippines the author read through eighteen years of the Mindanao Times , a reputable, remarkably long-lived, and generally ”pro-America” Davao City newspaper (it routinely prints U. S. Information Service releases). During this laborious task, two articles were discovered which related to the 1958 affair. Both are here reprinted in full. U.S. PLANE FORCELANDS: STIRS TALKS IN DAVAO Navy Bomber’s Wings Without Usual Marking Wing Tip has Gaping Hole With Busted Pipeline Say Landing Due to Engine Defect A U.S. -

Air America: Administration and Financing

Company Management, Administration, and Ground Support II – at the times of Air America Part 1: 1959-1973 by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 24 August 2015, last updated on 10 July 2020 IV) Widening operations: The CAT-Air America-Air Asia complex (April 1959-1973) As has been shown in the first part of this file, the CIA, as the owner of CAT Incorporated (renamed Air America Inc. in 1959), controlled the Company by committees that met at Washington or New York and whose decisions had to be executed by the Management in the “Field” that is in the Far East. In 1989, the CIA described Air America even as “the largest of the CIA’s proprietaries”: Background material about Air America Inc. Memorandum for the record dated 14 August 1989, sent to Congressman Jack Russ upon his request1 It will also be recalled that a CIA-Proprietary was not equivalent to a US Government-owned corporation. For the CIA-Proprietary can do and did covert operations, as it was controlled only by CIA Headquarters2 and by a US Government Committee formerly called the 303 Committee,3 but not by the Congress. Government-owned corporations, however, have to be incorporated by Congress and have to submit their budgets to Congress, so that their actions are more or less public and evidently exclude covert operations.4 As the holding company of the complex, the Airdale Corporation, later renamed The Pacific Corporation, was responsible for financing. The Board of Directors, which was composed of CIA men and what has been called “business-friends of the Agency”5 and whose Executive Committee made the decisions in day-to-day business, was responsible for having the guidelines of CIA policy observed by the Company. -

Air America Japan, but the Korean War, Which Began on 25 June 1950

CAT and Air America in Japan by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 4 March 2013 I) A new beginning: As has been shown elsewhere, Civil Air Transport, after its glorious days during the civil war in mainland China, had to go into exile on the Island of Formosa in late 1949. With only very few places left where to fly, CAT had enormous financial problems at the end of December 1949, although on 1 November 1949, CAT and the CIA had signed an agreement by which the CIA promised to subsidize CAT by an amount of up to $ 500,000.1 In order to prevent the fleets of China National Aviation Corp. (CNAC) and Central Air Transport Corp. (CATC) detained at Hong Kong‟s Kai Tak airport from falling into the hands of Communist China, General Chennault and Whiting Willauer, the main owners of CAT, had bought both fleets from the Nationalist Government of China against personal promissory notes for $ 4.75 million – an amount of money they did not have2 – and registered all aircraft in the United States to Civil Air Transport, Inc. (CATI), Dover, DE on 19 December 1949. But it was not until late 1952 that the former CATC and CNAC aircraft were awarded to CAT by court decision,3 and so this long lasting lawsuit, too, meant enormous financial expenses to CAT. Finally, in order to prevent their own fleet from falling into the hands of Communist China, on 5 January 1950, the Chennault / Willauer partnership transferred their aircraft to C.A.T. Inc – not identical with CATI, although resident at exactly the same address, that is at 317- 325 South State Street, Dover, Delaware.4 C.A.T.